Communication skills

2.1 Turning anxious patients into satisfied ones

Patient satisfaction is vital for a thriving optometric practice as it is associated with greater patient retention, increased patient referrals, greater profitability and lower rates of malpractice suits.1 The medical research literature consistently indicates that patient satisfaction is linked with health care practitioners having good communication skills: being able to explain diagnoses, prognoses, treatment and prevention using clear, non-technical terms1 and being honest, empathic and able to listen well and address patient concerns.2

2.1.2 Understanding patient anxiety

Poor patient satisfaction is linked with pre-consultation patient anxiety.3 A significant number of patients are anxious about attending for an optometric exam4,5 and particularly fear receiving ‘bad news’ of one form or another.5 Anxiety reduces patient–practitioner communication and causes reduced attention, recall of information and compliance with treatment.5 This limits the usefulness of the examination as an anxious patient is unlikely to provide a full case history and reveal all their visual problems, unlikely to attend appropriately to your instructions, could provide unreliable responses in the subjective refraction and could easily misinterpret or forget what you said about their diagnoses and management plans. Possible reasons for patient anxiety include:

(a) Being told they need glasses.3 This can be a worry for both pre-presbyopic6 and presbyopic patients4 who are often concerned about the effect on their appearance.

(b) Fear of vision loss. Particularly true of elderly patients where eye disease is a greater risk.4 This could be due to the fact that a friend or family member has lost their vision due to eye disease and this could even have been detected at a routine visit to their optometrist.

(c) Cost issues. Some patients are very worried about the potential cost of glasses and contact lenses4,6 and even that they will be ‘sold’ glasses that aren’t necessary.

(d) Fear of making a mistake. Some patients are worried about making mistakes during the subjective refraction part of the examination. This may be because they believe that a mistake on their part could lead to the provision of an incorrect refractive correction in their glasses and/or are worried about feeling foolish if they make a mistake (note that some patients can feel educationally inferior to the optometrist7).

(e) Fear of increased ametropia. Young ametropes can worry that the increasing myopia or hyperopia will mean thicker and less attractive glasses. Vision-related quality of life has been shown to be reduced in pre-presbyopic spectacle wearers with high prescriptions.8

(f) Being told that they cannot wear contact lenses any more. Young contact lens wearers typically report a better vision-related quality of life than spectacle wearers8 and some may worry about being told that they cannot wear contact lenses any more.

(g) Adaptation problems. Many patients report concerns about being able to adapt to their new glasses.4

(h) Fear of looking foolish. Some patients are very tentative about admitting some of their concerns about their vision in case they are made to look foolish by raising the issue. Concerns about vitreous floaters are a typical example of this.

2.1.3 Building a rapport: relaxing the patient

A good communicator will be able to relax an anxious patient and increase patient satisfaction with the eye exam.1,3 There are many ways to relax a patient and build a rapport and these include:

(a) Provide information about the eye examination (via a leaflet or website, section 2.6) prior to the appointment as this can reduce anxiety and improve satisfaction with the consultation.3,9

(b) Provide a comfortable and welcoming setting in the practice waiting room. Comfortable chairs, a selection of magazines, some low level music, etc., can all help to relax the patient. Framed copies of your qualifications, either in the waiting room or the exam room, can provide reassurance to some patients.

(c) Your attire is important and medical research suggests that patients prefer a formal, ‘professional’ appearance.10 This is linked with patients’ trust and confidence, particularly if providing sensitive information in the case history.

(d) First impressions count and some practitioners like to greet a patient by name and escort them to the examination room.

(e) Beware of making the examination room frightening to the patient. For example, a poster containing a cross-sectional diagram of the eye can be very useful for explanation purposes, but one that portrays a variety of eye diseases is not likely to relax the patient!

(f) Change the chair height to ensure you are at the same eye level as the patient.7

(g) Some practitioners like to chat about non-clinical issues (weather, holidays, sports teams, parking, etc.) prior to the examination to help relax the patient. In this respect, it can be useful to make a note of any relevant information (a child’s favourite sport, sports player, team, author; the patient’s pets and their names, their children successes, etc.) to allow you to start a conversation at subsequent visits.

(h) Your posture and style should be relaxed but attentive. Maintain regular eye contact and use the patient’s name at appropriate times during the eye examination.

(i) An open question is typically used to start the case history (section 2.3.1) as this allows the patient to tell you about any problems with their vision or glasses. A balance is required between allowing the patient plenty of time to discuss their problems and not rushing them but at the same time retaining control of the discussion. You need to ensure that the patient feels that you have fully listened and understood their problems and you may even need to allow the patient to talk about information that you know is not necessary from a diagnostic viewpoint. However, you also need to develop the skill of being able to interrupt an overly talkative patient without appearing rude.

(j) Some patients are very shy and an open question provides little information and may make the patient feel uncomfortable. Closed questions can be useful at the beginning of the case history with such patients. An open question can be used later in the case history if the patient relaxes and conversation becomes easier.

(k) Listening is a hugely important communication skill. It is vital that you have fully listened to the patient and understood their problems (e.g. Dawn et al.2). There are a variety of ways that indicate to the patient that you are listening and these include maintaining eye contact and demonstrating attention by nodding and/or using affirmative comments such as ‘I see’, ‘I understand’, ‘OK, go on’, etc. Listening is also indicated by using follow up questions to comments, such as asking about the location, onset, frequency, etc., of headaches when the patient indicates that they suffer with them. Finally, summarising the patient’s problems at the end of the case history (section 2.3.1, step 11) is a very useful way of indicating to the patient that you have listened to what they have to say and fully understand what problems they are having, whilst it also provides the patient with an opportunity to inform you if you have missed anything.

(l) Provide a brief explanation to the patient of each test that you use during the eye examination. Suggested information, in lay terms, is provided for each test described in later chapters.

2.1.4 How to improve your communication skills

All students should gain adequate communication skills. You are taught which questions to ask during the case history, what instructions to give for each test, an explanation of why you are doing the test and what to record. In clinics, you will be taught how to provide diagnoses, prognoses and management plans. How do you become a better communicator? You can obviously read about what they are. A brief summary is provided here and further reading is suggested (e.g., Ettinger7). Video recording your case history and/or eye examination can be a valuable tool and will particularly highlight your non-verbal communication skills. Review the video with a colleague and critique your listening skills, your tone of voice, your attentiveness and your eye contact. A helpful quality about communication skills is that you can learn them anywhere and from anybody. Obviously observing an optometrist or other health professional who is popular with patients could be particularly beneficial. You can also learn by experience so that any summer job that involves working with the general public can be beneficial. Indeed, when supervising in student clinics, it is very obvious from the level of communication skills which students have had jobs that involved working with the general public and which ones have not.

2.2 Record cards and recording

In the descriptions of clinical procedures in the following chapters, a subsection on recording is included in each case. It is essential that all test results (including the ‘results’ from case history) are recorded. If they are not recorded, subsequent legal analysis of the records will conclude that they were not performed. Clearly, it is important to write legibly on your record cards, for legal reasons and so that they can be read by colleagues who may examine the patient subsequently. Illegible record cards are a significant source of error in primary eye care.11 Similarly, it is hugely important to ensure that record cards are stored in an efficient and organised manner.11

2.2.1 SOAP

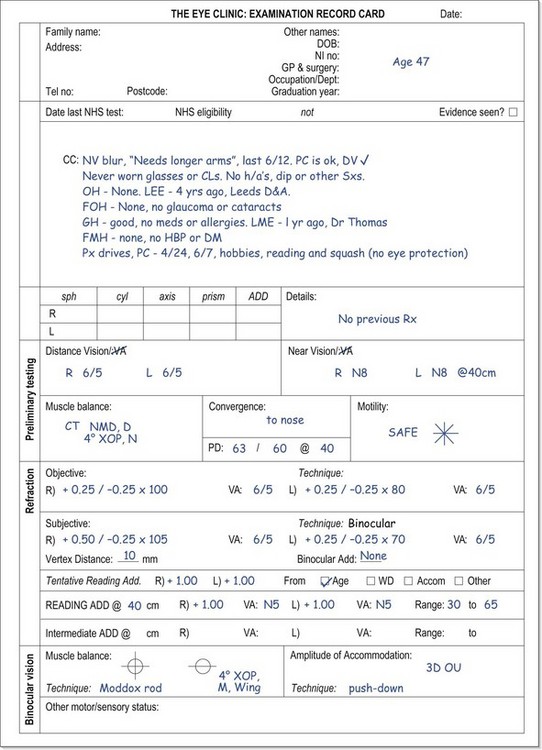

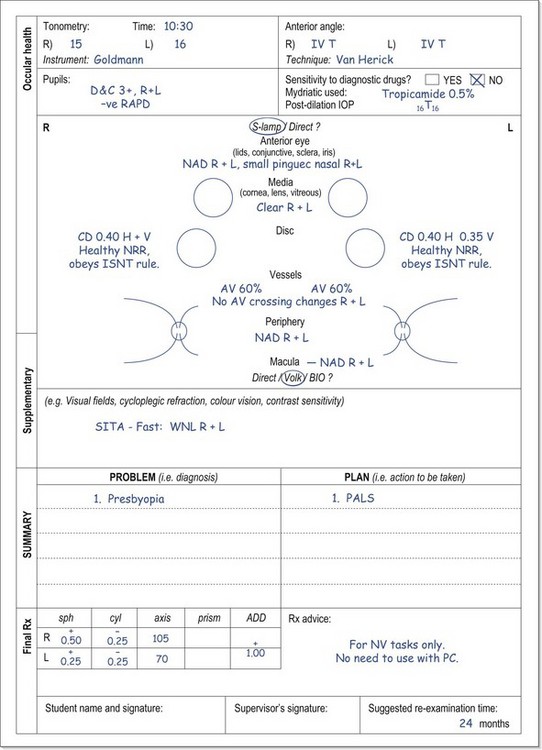

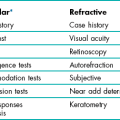

The format of record cards can vary hugely. Many include various designated areas for certain test results that are commonly performed. This is an attempt to save time, as you do not have to write down the test or procedure used, but merely the result. As students will typically use the database style of examination, university clinic record cards (e.g. Figure 2.1) tend to include the majority of tests performed. More experienced optometrists will tend to use the problem-oriented examination which uses the acronym SOAP for its record format.12 The record card itself is a plain white sheet. This reflects the fact that this style of examination is distinguished by its variability, so there is little point in making boxes for individual tests. SOAP stands for Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan. The subjective information is that obtained from the case history and the objective information is the various test results obtained during the examination. The assessment and plan refer to the problem-plan list that is described in detail in a later section. These sections must ‘close the loop’ and link the assessment and plan back to the complaints of the patient.

2.2.2 Computer-based systems

Computer-based systems avoid the problem of illegible records and should reduce the likelihood of lost records (assuming appropriate backup arrangements), which are surprisingly common with paper records.11 Systems vary widely and will continue to improve, but other advantages of current systems include that information from a previous record can be uploaded and then amended with information from the current examination (this can also be done for the right and left eyes); they can be linked to digital ocular photographs; the systems typically learn the information you input and subsequently provide it in drop-down lists and referral letters are easier to produce and print. Disadvantages include the inability to sketch various features (e.g. cataract and fluorescein staining patterns) if digital photography of both the external and internal eye is not available; getting used to different systems can be difficult for locum optometrists; going to a complete computer system means that some companies scan old paper records which can become more illegible by that process; copying information from previous records or the other eye can mean that you forget to put in details; drop down lists can become very long and it can be difficult to get an overall picture of a patient because of the fragmented nature of the information. The latter can mean it is difficult to highlight important details as with a paper record card you can write it in large capitals/highlighter on the front page.

2.3 The case history

2.3.1 Procedure (Summary in Box 2.1)

1. Make sure that the room lights are on before the patient enters the examination room.

2. Consider the patient’s age (gender and ethnicity may also be important) as this can provide useful clues to what their problems might be given the known epidemiology of certain ocular problems. For example, a 47-year-old patient attending for their first eye exam for many years is likely to complain of presbyopic-related symptoms.

3. Observe the patient’s stature, walking ability and overall physical appearance. Pay particular attention to any head tilt or obvious abnormalities of the face, eyelids and eyes that will require further investigation such as facial asymmetry, lid lesions, ptosis, epiphora, entropion, ectropion, a red eye or strabismus.

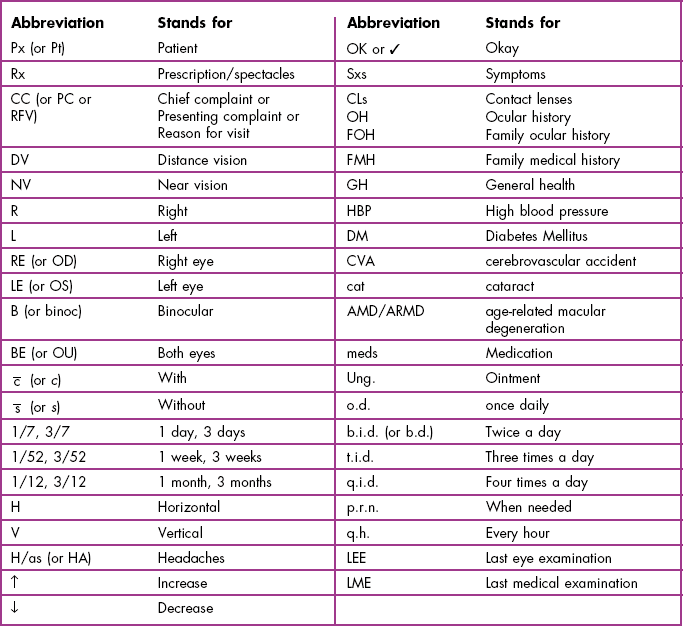

4. You should sit about 1 m from the patient at eye level. Your posture and style should be relaxed but attentive. Lean slightly forward towards the patient. Try to avoid long silences while writing notes and learn to write down answers in abbreviated form (see Table 2.1) as the patient is talking, while retaining intermittent eye contact.

5. Chief complaint (CC) or reason for visit (RFV): Determine the chief complaint by asking a very general open-ended question such as ‘Do you have any problems with your vision or your eyes?’ or ‘Is there any particular reason for your visit, Mr Smith?’

6. In a patient who reports no problems to the question above and is attending for their regular annual/biennial examination, ask the following questions (see recording example in 2.3.3.a):

(a) If the patient wears glasses (ask if you are unsure), you need a complete description of them. This may include:

(i) ‘When do you wear your glasses?’

(ii) ‘How is your distance vision in your glasses?’ followed up by ‘Do you feel it is as good as it was when you first got them?’ This can be adapted to suit the patient. For example, a student could be asked ‘Any problems reading from the whiteboard?’ and ‘Is everything clear on the TV?’

(iii) ‘Any problems with reading with the glasses?’

(iv) ‘How is your distance/near vision without your glasses?’

(v) ‘How old are your glasses?’

(vi) ‘How many pairs of glasses do you have?’

(vii) ‘Where did you get these glasses from?’

(b) If you are unsure, ask if the patient wears contact lenses. If they do wear lenses, even if only occasionally, then you need a complete description of the contact lenses used:

(i) ‘What type of lens are they?’ (soft, gas permeable, toric, multifocal, etc., and brand if known)

(ii) If relevant (i.e. not single use lenses): ‘How often do you replace your lenses?’ and ‘What care solutions do you use?’

(iii) ‘How long do you usually wear the lenses each day?’ and ‘How many days per week?’ The first question can be confirmed by asking when they typically put their lenses on and when they typically remove them as average wearing times are typically underestimated.

(iv) ‘How many hours of comfortable wear do you get with your contact lenses?’

(v) ‘How is your vision with contact lenses and how does it compare with the vision you get with your glasses?’ If the patient wears both glasses and contact lenses, you will have to ask about visual symptoms (i.e. distance blur, near blur, headaches, eyestrain, etc.) for both forms of correction.

(vi) ‘Are you having any problems with your contact lenses currently?’

(vii) ‘When was your last contact lens aftercare and when is your next aftercare check scheduled for?’

(c) A patient who does not wear glasses or contact lenses should be asked about the clarity of the distance and near vision.

(d) Complete a symptom check by asking about the most common symptoms:

7. Patient reporting visual symptoms (see recording examples in 2.3.3b).

(a) L – Location/laterality. Examples:

• ‘Is it more blurred in one eye or is it the same in both?’

• ‘In which part of the head is the headache located?’ For a frontal headache, ask ‘Is it above one eye more than the other?’

• ‘Is the double vision in all directions of gaze or just one?’

(c) F – Frequency/occurrence. Examples:

• ‘How often do you get headaches?’ Prompt if the patient is unsure: ‘Every day? Once a week? Once a month?’, ‘Are they any better on weekends?’, ‘Do they tend to occur at any particular time of day? Morning mainly or evening?’

• ‘How often do you get double vision?’, ‘How long does it last?’, ‘Does the double vision occur after a lot of reading or at anytime?’

(d) T – Type/severity. Examples:

• ‘Did the blurred vision start suddenly or gradually?’ If sudden vision loss, ask ‘Was the vision loss partial or total?’

• ‘Is it a throbbing, sharp or dull headache?’

• ‘Is the double vision one-on-top-of-the-other or side-by-side?’

(e) S – Self-treatment and its effectivity:

• ‘How have you coped with the blurred vision?’(possibly by squinting, sitting at the front of the class, sitting close to the TV, using ready readers, borrowing a family member’s glasses, etc.)

• ‘Does anything make the headaches go away?’ ‘Do you take any painkillers for the headaches?’

(f) E – Effect on the patient:

• ‘How is your son’s school work progressing?’, ‘Does it affect your hobbies or sports?’, ‘Is your poor vision affecting how well you can do your job?’, ‘Have you restricted your driving?’, ‘How well do you manage driving at night?’

• ‘How badly do the headaches affect you?’, ‘Have you been to see your GP about the headaches?’

(g) A – Associated factors: ‘Are there any other symptoms associated with the problem?’

8. Completion of information gathering for a patient with a chief complaint.

9. Ocular history (OH) and family ocular history (FOH):

(a) If you do not already know, ask the patient when and where was their last eye examination (LEE).

(b) Ask whether the patient has had any previous eye injuries, infections, surgery or treatment. Follow up any positive responses by asking the patient how old they were at the time, who managed the condition and over what period and what treatment they received. For example, if a patient indicates they have amblyopia, discover the age they were diagnosed and whether and at what time they had an ‘eye-patch’, ‘eye exercises’, glasses or surgery.

(c) Family ocular history (FOH): An open-ended question such as ‘Has anybody in your family had any eye problem or disease?’ should be asked. This can be clarified by providing examples of common hereditary conditions (in lay terminology) for their age, gender and race if pertinent. For example, ask about any family history of cataract, age-related maculopathy and glaucoma for patients over 60, glaucoma for patients over 40, glaucoma for black (African American, African Caribbean) patients over 30, short-sightedness, squint or lazy eyes with children, colour vision for male patients attending their first exam.

10. General health information:

(a) ‘How is your general health?’ and add a follow-up question such as ‘… any high blood pressure or diabetes?’ If you receive a positive response, ask the patient how long they have had the condition. For some conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, ask whether the condition is well controlled.

(b) ‘Do you take any medications?’ If you receive a positive response, ask the patient how long the medication has been taken, the present dosage and the number of tablets taken per day.

(d) Family medical history (FMH): Ask an open-ended question, clarified by examples, such as ‘Has anybody in your family had any medical problem?’ This can be clarified by providing examples of common hereditary conditions such as ‘any diabetes or high blood pressure in the family?’

(e) Last medical examination (LME): Ask the patient when they last visited their physician and obtain the name of the physician.

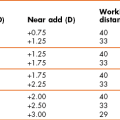

11. Vocation, sports, hobbies, computer use and driving: Determine the patient’s visual demands, including the safety hazards/protection for the patient’s vocation as well as their sports and hobbies. For presbyopic patients, you need to discover the distance used for reading and other near tasks and the use of any additional reading lights (e.g., anglepoise or goose-neck lights, etc.; section 4.14). Question whether they use a computer on a regular basis and determine approximate weekly usage. Determine whether the patient drives and whether they wear contact lenses or glasses when driving. It can be particularly useful to ask patients abut contact sports (football, rugby, hockey), swimming, fishing and racquet sports and whether ametropic patients wear their glasses or contact lenses for these sports and activities, so that they can be advised appropriately (see section 2.4.3).

12. Summarise the case history: Summarise the pertinent information from the case history and allow the patient to clarify any misunderstanding on your part or to add any additional information that has been missed. For example, ‘So, Mrs Wilson, the main reasons for your visit are that reading has become a little difficult, even with your glasses, and that you particularly want me to perform all the glaucoma diagnostic tests because your mother has glaucoma. Is that correct?’

13. Remember that a case history continues throughout the examination. Certain signs or test results during the examination may suggest the need for further questioning.

2.3.2 Additional questions regarding public health issues

Increasingly optometry is becoming involved in public health issues, so that your case history may include questions regarding falls and cigarette smoking (section 2.3.4d). Elderly patients, particularly those with risk factors for falls, should be asked: ‘Do you have any problems with falls at all?’ or ‘Have you had any falls in the last year?’

2.3.3 Recording

Both positive and negative patient responses must be recorded. Remember that from a legal viewpoint, if the response was not recorded the question was not asked. Abbreviations are essential to allow a sufficiently complete case history to be recorded, while retaining intermittent eye contact with the patient, which is required for good communication and building a rapport. Use standard abbreviations (Table 2.1) and avoid personal ones. Using the patient’s own words, recorded in quotation marks, can be useful. Here are some examples:

(a) Case Hx: 68-year-old Asian female (retired).

RFV: Routine 2 yr exam. No problems. DV and NV good  Rx. Bifs, worn all time. No ha, eyestrain, pain, dip or other Sxs.

Rx. Bifs, worn all time. No ha, eyestrain, pain, dip or other Sxs.

OH: 1st wore bifs age 50, this Rx 2 yrs old. No other OH. Never worn CLs. LEE: 2 yr, Dr Armitstead, Otley. No FOH.

GH. Type II DM for 15 yrs, Metformin 500 mg bid, well controlled; High BP for 15 yrs, Propranolol 100 mg, bid, well controlled, CU every 6/12; High cholesterol last 2 yrs, ‘Statins’ 40 mg od now under control; Aspirin od, last 3 yrs to ‘thin blood’ and ‘help avoid heart attack’, CU every 6/12; Non-smoker and no history of falls.

LME: 2/12, Dr Brownlee, Bramhope. No allergies, FMH: None. Hobbies: Walking, watching TV. No PC use. Doesn’t drive.

(b) 25-year-old Px. Caucasian. Secretary.

CC: DV ↓ for driving,  CLs and >

CLs and >  specs, esp. @ night last 2/12, OD blur>OS. Better

specs, esp. @ night last 2/12, OD blur>OS. Better  squinting. NV

squinting. NV  CLs and specs OK. No HA, dip, eyestrain, discomfort. No other Sxs.

CLs and specs OK. No HA, dip, eyestrain, discomfort. No other Sxs.

OH: Specs ∼ 4 yrs old – not updated last EE 2 yrs ago. Worn soft CLs last 6 yrs: 6/7 and ∼10/24. Comfortable for ∼8/24 then sl. gritty. Monthlies brand X, multipurpose sol’n brand Y. Fitted by Dr Adams, Leeds. Last AC 18/12 ago. Overdue a check. No probs  CLs and no other OH. FOH: parents both myopic.

CLs and no other OH. FOH: parents both myopic.

GH = OK, no meds. No allergies. Non-smoker. LME: 12/12, Dr Campbell, Hull. FMH: pat grandfather has heart disease.

2.3.4 Interpretation

(a) General health issues: A general question of ‘how is your general health?’ can be misleading because some patients think that systemic diseases are not relevant when they are borderline or are controlled by medication. It is better to follow up the initial question and give some examples of what is being specifically sought after, such as ‘… any high blood pressure or diabetes?’ If you get a positive response to this question, you must ask the patient how long they have had the condition as ocular effects of systemic diseases are more likely the longer the patient has had the condition. For example, the duration of diabetes is a major risk factor for diabetic retinopathy.13 If the patient has diabetes or hypertension, ask how well the condition is controlled. The risk of diabetic retinopathy is greatly reduced with good glycaemic control in diabetic patients14 and by good blood pressure control in a patient with diabetes and hypertension.15 An alternative or additional question for a female who may be pregnant is to ask the patient if they see their physician or a practice nurse regularly (asking about the last medical exam helps in this example). The medical history may indicate that you should particularly look for certain ocular disorders which manifest in certain systemic disease (most commonly diabetes) and whether it is safe to use certain diagnostic drugs such as phenylephrine.

(b) Medications and adverse effects: It is important to ask patients whether they are taking any medication even if they indicate that their general health is fine. Patients may believe their general health is fine because it is controlled by medication. Patients may also be taking medications, but are unsure why because the medical diagnosis was not properly explained or was poorly understood. It is important to determine any medications that the patient is taking as some can have adverse ocular effects. For example, it is well known that beta-blockers prescribed for systemic hypertension can cause dry eyes which will have implications for successful contact lens wear and oral corticosteroids can cause posterior subcapsular cataracts. Typically, the higher the dosage of the drug and the longer the patient has been taking it, the more likely are adverse ocular effects. Therefore it is important to ask about the dosage and number of tablets taken per day and how long they have taken the drug. Note that patients may not consider ‘over-the-counter’ tablets, such as travel sickness pills, antihistamines, sleeping pills and painkillers as medications, so it can be useful to ask about them specifically, particularly with patients with unexplained symptoms. Similarly, female patients may not consider birth control pills to be medication, yet the drugs in these pills can have adverse ocular effects. Topical eyedrops for hayfever will have implications for contact lens wear and should be instilled at least 20 minutes before lens insertion.16

(c) Occupation, sports and hobbies: This information is very useful in the eye exam when determining the near add. For example, you want to know whether the reading or near addition needs to provide clear vision for computer work, reading, sewing or all three. It is particularly important when providing advice to the patient about whether glasses or contact lenses should be worn for sports and hobbies and whether protective eyeware is necessary (see section 2.4.3).

(d) Falls and cigarette use: A history of falls is an important risk factor for subsequent falls and patients at high risk of falling need to be identified as they should have more regular eye examinations, earlier cataract surgery and an altered spectacle prescribing strategy (section 4.15).17 Falls are very common in the elderly, with about a third of people over 65 falling at least once per year and they cause significant morbidity and mortality, with more than 80% of accidental deaths in this age group being due to falls.17,18 Other risk factors include being over 75 years of age, using more than three medications, antidepressant use, systemic conditions that reduce mobility, cardiac problems, etc.

(e) Cigarette smoking is a significant preventable risk factor for both age-related macular degeneration and cataract and this is well known to optometrists.19 However, it would appear that some optometrists do not ask about cigarette smoking and/or do so at initial examinations only and that relatively few assess whether patients want to stop smoking and provide support for tobacco cessation.20 This may vary across countries and it seems likely that optometrists would be more involved in this process where there are national social marketing campaigns linking blindness and smoking. Australia became the first country to include a picture warning label on cigarettes to link blindness and smoking in 2007 and this has increased levels of awareness compared to other countries that have not yet introduced these warning labels.21 Optometrists are in an excellent position to help people to stop smoking because fear of blindness is a potentially important motivator.22

(f) Problem-oriented exams for experienced clinicians: Once all the demographic and verbal information is accurately collected the experienced examiner should have a list of tentative diagnoses in mind for each of the identified problems. The remainder of the eye examination is based on testing to differentiate which of the tentative diagnoses is correct as well as gathering information so that each system (visual function, refractive and binocular systems and an ocular health assessment; Table 1.3) has been assessed.23,24 This means that the case history decides to some degree which tests/procedures you are going to perform. Some differential diagnoses, such as a red eye, may rely heavily on case history.

2.3.5 Most common errors

1. Not fully investigating the patient’s chief complaint.

2. Not maintaining intermittent eye contact with the patient.

3. Not using standard abbreviations.

4. Not following through the case history in an organised manner.

5. Forgetting that the case history taking can continue throughout the examination.

6. Assuming the same information is still current from the previous case history.

2.4 Discussion of diagnoses and management plan

Patients expect you to provide information about the cause of their visual problems, the prognoses and any management plans, all in a clear non-technical language.1 See online videos 2.2 to 2.4![]() .

.

2.4.1 Cause of the chief complaint: provide the diagnoses

1. Indicate the eye examination has finished and you wish to discuss your findings. You may put down your pen and even turn off the projector chart. Make eye contact with the patient and make sure that the patient is comfortable and attentive.

2. Introduce your diagnosis by reminding the patient of their symptoms and then link them with the diagnosis.

3. Explain what the ametropia or eye disease is in simple lay terms. Give the patient time to digest the information and encourage them to ask questions. Most computer-based optometry programmes include an atlas of photographs and diagrams to help you in this explanation.

4. Demonstrate any refractive correction changes to the patient. The effect of any refractive correction changes can be shown to the patient by alternatively showing the patient the vision (distance and/or near) obtained with their optimal refractive correction in a trial frame compared to their current glasses. This can be awkward and it can be easier, if there are negligible cylindrical changes (which is relatively common), to place appropriate spherical trial case lenses over the top of their current glasses to allow a comparison.

2.4.2 Offer reassurance where possible

1. If the cause of the chief complaint or other problem is not determined, then present your negative findings in a positive manner.25 For example, non-ocular headaches: ‘ I do not believe that your headaches are due to a problem with your eyes or vision, Mr Wiggins. Your eyesight is excellent and there is no need for glasses/change in glasses; your eye muscles and focusing muscles are all working normally and are working well together and there is no sign of eye disease from any of the tests that I have performed.’

2. If the condition can be diagnosed, but no treatment is necessary, in addition to providing diagnosis and prognosis information in lay terms, provide reassurance to the patient that they were correct in attending for examination.25 An example would be pingueculae.

3. If a patient’s attendance for an eye examination was because of increased risk of a certain condition, but you found no problems, provide reassurance that you have performed the necessary tests and confirm the reasons that the patient should continue to regularly attend for examination. An example would be a patient with a family history of glaucoma that showed normal values for all assessments.

4. Reassurance can be particularly beneficial to a patient with non-organic/psychogenic visual loss (section 4.6.3).26,27 First, present your negative findings in a positive manner and highlight that there is no need for glasses, that the eye looks healthy and that the eye’s muscles work well together. With children, follow this up by asking them whether anybody they know well wears glasses. This can be followed up by asking ‘Do you want to wear glasses like your friend/dad?’ A discussion with the parent can highlight that social problems at home or school can cause this condition and/or their child may be seeking extra attention (is there a new baby in the home?). In adults, you may also discuss the effects of stress, anxiety and mild depression on general health and that it can also cause visual loss. It can then be useful to ask the patient if there are any areas of stress in their life that could be causing the problems.26 In all cases, finish by repeating the reassurance that the eyes are healthy and their vision is good and arrange to see them again in 3–6 months. In many cases, this reassurance is all that is needed for recovery.26,27

2.4.3 Discussion of treatment or further investigation

1. Present the various treatment options and/or referral options available, with advantages and disadvantages, and involve the patient in the decision of the most appropriate management.

2. Explain when the patient should wear glasses. Do not assume that the patient will understand when to wear them. For example, if a patient’s chief complaint was distance blur when driving, it may not be enough to indicate that they should wear the glasses for driving and assume they understand that they can wear them for any other distance vision task. Indicate that the glasses could be used for TV, cinema and theatre, watching sports and when walking about outside if the patient wants to wear them for those tasks. In this regard, it is very important to inform a patient who drives without glasses whether they are legally allowed to do so.

3. Discuss possible adaptation problems (section 4.15). If making a relatively large change in refractive correction, particularly with older patients, warn them of possible adaptation problems. This is most important when making any cylinder changes, particularly with oblique cylinders. Take note of a patient’s previous reaction to refractive correction change. It is better to overestimate the time that adaptation will take rather than underestimate the time.

4. Occupation, sports and hobbies: Most clinicians tailor spectacle lens information to match the patient’s requirements, based on the patient’s occupation and hobbies.4 Contact lens wearers are advised not to wear their lenses for swimming and to wear prescription swimming goggles, or to wear a single use lens with standard swimming goggles, and dispose of the lens immediately after swimming.28 Ametropes who play contact sports benefit from using contact lenses as they usually do not wear their glasses while playing, although some football/soccer players do wear glasses and should be informed of protective eyewear.29 Contact lenses will also have benefits for many other sports and leisure activities in that they can provide a wider field of view and they are not affected by fogging up or rain, for example. At the same time, contact lenses provide no eye protection, which can be important for sports that involve a high speed ball/puck and a stick, such as cricket, baseball, hockey (ice and field), lacrosse and squash.29 The potential eye injuries from squash are particularly poorly known and appropriate protective eyewear should be recommended.30 Finally, safety glasses may be needed for DIY enthusiasts and keen gardeners and fishing is made easier and more comfortable with polarised sunglasses.

5. Provide the patient with an appropriate information leaflet and website details, if available, and indicate that they can return or phone with any questions.

6. Instructions regarding contact lens care and maintenance and ocular disease management should be clear and unambiguous, with appropriate emphasis placed on the importance of procedures from a safety viewpoint.31 Written instructions at an easy reading level (age ∼8–12 years) are essential.31,32 Checking compliance, explaining the benefits of compliant behaviours and repeating the instructions at follow-up visits can improve matters.31,33,34

2.4.4 Giving bad news

With patients with an untreatable condition, be aware that giving bad news is known to be difficult for practitioners and can cause some clinicians to delay or avoid it or provide overly optimistic information.35 Remember that although the information will be very sad for the patient, they need factual, honest information, provided empathically, to properly plan for the future. Points to consider include the following:35

1. Indicate the eye examination has finished and you wish to discuss your findings. You may put down your pen and even turn off the projector chart. Make eye contact with the patient and make sure that the patient is comfortable and attentive. It can be helpful to have some tissues ready in case the patient becomes upset. It can be very useful to explain all this information to one or two family members if they are present35 and if the patient is happy for you to do so.

2. Introduce your diagnosis by reminding the patient of their symptoms and then link them with the diagnosis. Explain what the eye disease is in simple lay terms. Give the patient time to digest the information and encourage them to ask questions.

3. For a patient with macular degeneration, for example, you should explain that they will not go ‘blind’ and should keep their peripheral vision. However, at the same time you must be honest and do not attempt to avoid difficult questions or even ‘sugar the pill’.36 Indicate that their central, detailed vision that allows them to drive, read and see faces, is likely to get worse. Blunt statements such as ‘I am afraid that there is nothing more that we can do’ are not helpful. This may be correct for conventional treatment with glasses, but low vision aids may be helpful for a variety of tasks, household modifications can be made and smoking cessation can slow progression.37,38 Note that there is some debate regarding the usefulness of multivitamin supplements.39

4. Empathic statements such as ‘I know this is not what you wanted to hear. I wish the news were better’ can be helpful.35

5. You need to be aware of the possible emotional responses to such news. Various models have been proposed and a common model suggests stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. These stages are not universal and some patients skip stages while others get ‘stuck’ at a particular stage. In the denial stage, patients will often seek a second opinion. You should not see this as a slight on your ability as a clinician and you may even suggest it to a patient who is openly in denial when you first tell them the news.

6. Explain the prevalence of the condition. This indicates that they are not alone. It can be useful at this point to discuss support groups and local agencies.

7. Discuss the availability of low vision aids and what help they could provide. In this respect, remember the stages of response to vision loss. Patients are unlikely to have the motivation to successfully use low vision aids when depressed. Do not give up on these patients. As and when they overcome the depression and accept their vision loss, low vision aids may usefully be provided.

8. Information leaflets and/or websites are particularly useful in these situations as the patient’s shock at the initial news may mean that much of the remainder of your discussion is forgotten.

2.4.5 Prognosis

1. Explain what symptoms should disappear with the glasses and over what time period.

2. If appropriate (e.g., early myopes and presbyopes), explain that progression is expected and why. Advise young myopes that wearing their glasses will not make their eyes worse, it just gives then clearer vision. Also the patient should know that not wearing their glasses will not make their eyes worse.

3. Explain that a gradual reduction in unaided vision is expected in hyperopia with age. It is not uncommon for hyperopes to conclude that the glasses ‘ruined their eyes’ when their accommodation gradually declines and they need their glasses more and more often.

4. Be honest: If the condition is likely to get worse, you must inform the patient of this.

2.4.6 The next appointment

1. Finally, indicate to the patient when you would like to see them again.

2. If this is less than a standard time (typically 2 years or 1 year for children and the elderly), explain why.

3. Always inform the patient that if they have any problems with their vision or their eyes before that time, they should make an appointment to see you.

2.4.7 Most common errors

1. Using technical language and jargon to explain diagnoses and treatment plans.

2. Not explaining to myopes, hyperopes and presbyopes the likely progression of their condition.

3. Not explaining to patients when they should wear their glasses.

4. Not warning appropriate patients about possible adaptation problems.

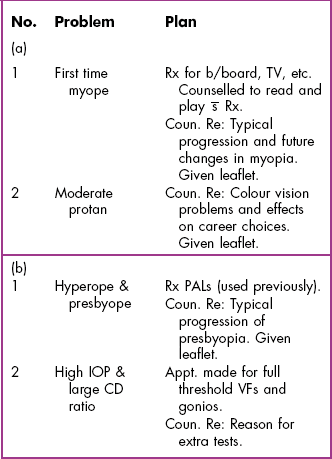

2.5 Recording diagnoses and management plans

1. It is important legally to document all your diagnoses, treatment suggestions, suggestions of referral, etc. Similarly, it provides valuable support when dealing with patients who return with complaints that you didn’t provide advice regarding the management of a certain condition.

2. It ensures that you must review the case history and discuss each of the patient’s symptoms and review the record card and deal with any significant findings.

3. In subsequent examinations of the same patient, a review of the problem-plan list provides a thorough and complete summary of the examination without having to read the whole record card.

2.5.2 Procedure

1. List each separate diagnosis in a column. Do not list the individual symptoms and signs that allowed the diagnosis. Order diagnoses with the most important first.

2. If a patient has symptoms for which no diagnosis has been made, include the symptoms in the problem list. Similarly, include any abnormal signs or test results for which a diagnosis was not yet possible in the problem list. By this method any problems you do not immediately understand are highlighted and this prompts the consideration of further investigation.

3. For each problem, outline a plan or a series of actions to be taken in an adjoining column. Consider including the following forms of plan:

Counselling is a fundamental element in patient management. Effective counselling requires that all diagnostic and therapeutic plans be clearly stated to the patient in terminology that they can easily understand.

2.6 Patient information provision

Information regarding the eye examination, diagnoses and management plans should be available, ideally by a variety of mediums, most commonly leaflets and websites. They are viewed by patients as valuable additional information to that provided verbally and information that can be referred to at a future time and for discussion with family members.40 They are seen to be particularly valuable given that patients are aware of the time limitations of clinical appointments. DVDs, e-mail and texts will likely become other ways that useful information can be provided to patients and may aid compliance of treatment and contact lens care.31,32,41

2.6.1 Leaflet and website content

(a) In addition to standard leaflets regarding myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, presbyopia and the common eye diseases, patients would prefer more information on eye examination procedures and an explanation of prescriptions.40

(b) Patients do not want educational material, which is common in current leaflets and websites. They would prefer practical problem-solving information about how they could help to look after their eyesight.40

(c) Contact lens instruction leaflets that provide a rationale for various procedures and links with adverse outcomes may help compliance.31,33

2.6.2 Leaflet and website style

(a) Less jargon: Research has indicated that patients find the information in currently available information leaflets and websites to contain too much jargon, with a poor layout of diagrams and text and inadequate or irrelevant explanations.40 Patients reported that leaflets and websites often included unexplained terms, such as ‘accommodation’ and ‘macula’, that were confusing, and that they relied on an excessively high level of previous knowledge.

(b) Lay terms: Information provided should be interesting, concise and with simple explanations written in lay terms.31,40

(c) Sections: Different topics should be organised into clearly labelled sections so that patients can identify particular sections that they are interested in.

(d) Diagrams: Diagrams should be provided in colour. Patients have reported that diagrams in currently available leaflets can be too small with difficult to read labels.40 Patients appear to prefer a brief explanation of the function of different structures if included, rather than just labelling them.40

2.7 Referral letter or report

2.7.1 Comparison of letter types

Structured referral sheets have a standardised format and various boxes to fill in. Structured referral sheets can save time and if well designed may reduce the possibility of the omission of pertinent information. Indeed, when combined with dissemination of guidelines from secondary care, they appear to improve the quality of referrals from primary care.42 However, non-specific optometry referral forms, such as the UK GOS18 form, can lead to the inclusion of irrelevant information and a lack of required details.43 Referral forms specifically designed for commonly referred conditions, such as cataract and suspect open-angle glaucoma, particularly when supported by referral guidelines for such conditions, are likely to improve referral quality.43 Structured referral sheets can lead to vital information being left off the referral, such as the optometrist’s name and even the practice address.44 Well-written referral letters are important to help develop a good relationship with secondary eye care personnel and increase the likelihood of feedback being obtained regarding referrals. A lack of feedback appears to be a significant problem in some areas,11 and without it the optometrist cannot learn from the process and improve the quality and appropriateness of referrals.

2.7.2 Procedure for producing a personalised referral letter

1. Indicate to the patient that you will be sending a referral letter/report to another person or office. You should inform them of the reason for the referral or report.

2. Write the letter on headed notepaper that includes your practice address and contact information. The letter should ideally not be hand written, as this will make it less legible.

3. Include the date and the recipient’s name and address at the top of the letter.

4. Begin the letter with the patient’s name, address, date of birth (you may need to distinguish between several people with the same name and even between two people with the same name and address), appointment date and file number (if applicable).

5. Remember that the person you are writing to is likely to be very busy, so they want to read only essential information. Do not include information that is irrelevant to the referral as this could result in your letter not being read or being skim-read and misinterpreted.

6. A likely outline of a referral letter would be:

(a) Provide a diagnosis or tentative diagnosis if possible.

(b) Indicate the relevant symptoms and signs (if any)

(c) Indicate if there is any urgency in the referral.

(d) If appropriate, you might indicate what further investigations or treatment you believe to be necessary.

(e) Request a reply regarding the outcome of the referral. This may require the patient’s written consent.

(f) Indicate if you have copied the letter elsewhere (typically to the patient’s general physician).

7. If referring a patient because of cataract (the most common referral letter, see Box 2.2) also include:

8. A likely outline of a report would be:

(a) Thank the referring person (if applicable).

(b) Indicate the relevant symptoms and signs.

(c) Provide a diagnosis or tentative diagnosis if possible.

(d) If a diagnosis is not possible, indicate which tests were performed and any pertinent results.

(e) Indicate any management plan and the time of your intended follow-up appointment.

9. Make sure your spelling is accurate and grammar correct. Spelling and grammar checkers are available on all modern word processing packages.

10. Present the information at a level suitable to the recipient’s knowledge. However, do not automatically assume that lay terms are appropriate in a letter to a non-medical person. It may be best to use the correct term with the lay term in brackets to avoid offence. For example, in a letter to a teacher, you may include a statement that ‘David has myopia (short-sightedness) …’

11. Sign the letter with your preferred title and qualifications.

12. Keep a copy of the letter for the patient’s file. If the letter or report was not to the patient’s GP/physician, you may be required to send them a copy. If it is not a requirement, it is usually good practice to do so.

References

1. Dawn, AG, Lee, PP. Patient expectations for medical and surgical care: A review of the literature and applications to ophthalmology. Surv Ophthamol. 2004;49:513–524.

2. Dawn, AG, Santiago-Turla, C, Lee, PP. Patient expectations regarding eye care: focus group results. Arch Ophthamol. 2004;121:762–768.

3. Court, H, Greenland, K, Margrain, TH. Evaluating the association between anxiety and satisfaction. Optom Vision Sci. 2009;86:216–221.

4. Fylan, F, Grunfeld, EA. Visual illusions? Beliefs and behaviours of presbyope clients in optometric practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:291–295.

5. Court, H, Greenland, K, Margrain, TH. Predicting state anxiety in optometric practice. Optom Vision Sci. 2009;86:1295–1302.

6. Pesudovs, K, Garamendi, E, Elliott, DB. The Quality of Life Impact of Refractive Correction (QIRC) Questionnaire: development and validation. Optom Vision Sci. 2004;81:769–777.

7. Ettinger, ER. Professional communications in eye care. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1994.

8. Pesudovs, K, Garamendi, E, Elliott, DB. A quality of life comparison of people wearing spectacles or contact lenses or having undergone refractive surgery. J Refract Surg. 2006;22:19–27.

9. Sjoling, M, Nordahl, G, Olofsson, N, Asplund, K. The impact of preoperative information on state anxiety, postoperative pain and satisfaction with pain management. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:169–176.

10. Rehman, SU, Nietert, PJ, Cope, DW, Kilpatrick, AO. What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118:1279–1286.

11. Steele, CF, Rubin, G, Fraser, S. Error classification in community optometric practice – a pilot study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2006;26:106–110.

12. Weed, LL. Medical records that guide and teach. New Engl J Med. 1968;278:652–657.

13. Moss, SE, Klein, R, Klein, BEK. The 14-year incidence of visual loss in a diabetic population. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:998–1003.

14. Shamoon, H, Duffy, H, Fleischer, N, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes-mellitus. New Eng J Med. 1993;329:977–986.

15. Stearne, MR, Palmer, SL, Hammersley, MS, et al. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. Br Med J. 1998;317:703–713.

16. Tabuchi, N, Watanabe, T, Hattori, M, et al. Adsorption of actives in ophthalmological drugs for over-the-counter on soft contact lens surfaces. J Oleo Sci. 2009;58:43–52.

17. Elliott, DB. Falls and vision impairment: guidance for the optometrist. Optom in Pract. 2012;13:65–76.

18. Black, A, Wood, J. Vision and falls. Clin Exp Optom. 2005;88:212–222.

19. Cockburn, DM. Is it any of our business if our patients smoke? Clin Exp Optom. 2005;88:2–4.

20. Kennedy, RD, Spafford, MM, Schultz, ASH, et al. Smoking Cessation Referrals in Optometric Practice: A Canadian Pilot Study. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88:766–771.

21. Kennedy, RD, Spafford, MM, Behm, I, et al. Positive impact of Australian ‘blindness’ tobacco warning labels: findings from the ITC four country survey. Clin Exp Optom. 2012:590–598.

22. Sheck, LH, Field, AP, McRobbie, H, Wilson, GA. Helping patients to quit smoking in the busy optometric practice. Clin Exp Optom. 2009;92:75–77.

23. Amos, JF. The problem-solving approach to patient care. In: In: Diagnosis and Management in Vision Care (JF Amos, ed.). Boston: Butterworths; 1987:1–8.

24. Elliott, DB. The problem-oriented examination’s case history. In: Zadnik K, ed. The Ocular Examination: Measurements and Findings. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

25. Blume, AJ. Reassurance therapy. In: In: Diagnosis and Management in Vision Care (JF Amos, ed.). Boston: Butterworths; 1987:715–718.

26. Lim, SA, Siatkowski, RM, Farris, BK. Functional visual loss in adults and children patient characteristics, management, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1821–1828.

27. Muñoz-Hernández, AM, Santos-Bueso, E, Sáenz-Francés, F, et al. Nonorganic visual loss and associated psychopathology in children. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2012;22:69–73.

28. Wu, YT, Tran, J, Truong, M, et al. Do swimming goggles limit microbial contamination of contact lenses? Optom Vision Sci. 2011;88:456–460.

29. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness, American Academy of Ophthalmology, Eye Health and Public Information Task Force. Protective eyewear for young athletes. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:600–603.

30. Eime, R, Finch, C, Wolfe, R, et al. The effectiveness of a squash eyewear promotion strategy. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:681–685.

31. McMonnies, CW. Improving contact lens compliance by explaining the benefits of compliant procedures. Cont Lens Ant Eye. 2011;34:249–252.

32. Shukla, AN, Daly, MK, Legutko, P. Informed consent for cataract surgery: patient understanding of verbal, written, and videotaped information. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:80–84.

33. Claydon, BE, Efron, N. Non-compliance in contact lens wear. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1994;14:356–364.

34. Edmunds, B, Francis, PJ, Elkington, AR. Communication and compliance in eye casualty. Eye. 1997;11:345–348.

35. Baile, WF, Buckman, R, Lenzi, R, et al. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302–311.

36. Hopper, SV, Fischbach, RL. Patient-physician communication when blindness threatens. Patient Educ Couns. 1989;14:69–79.

37. Binns, AM, Bunce, C, Dickinson, C, et al. How effective is low vision service provision? A systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:34–65.

38. Neuner, B, Komm, A, Wellmann, J, et al. Smoking history and the incidence of age-related macular degeneration – results from the Muenster Aging and Retina Study (MARS) cohort and systematic review and meta-analysis of observational longitudinal studies. Addict Behav. 2009;34:938–947.

39. Evans, JR, Lawrenson, JG. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (6):2012.

40. Fylan, F, Grunfeld, EA. Information within optometric practice: comprehension, preferences and implications. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2002;22:333–340.

41. Armstrong, AW, Watson, AJ, Makredes, M, et al. Text-message reminders to improve sunscreen use: a randomized, controlled trial using electronic monitoring. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1230–1236.

42. Akbari, A, Mayhew, A, Al-Alawi, MA, et al. Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2008.

43. Davey, CJ, Green, C, Elliott, DB. Assessment of referrals to the hospital eye service by optometrists and GPs in Bradford and Airedale. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2011;31:23–28.

44. Lash, SC. Assessment of information included on the GOS 18 referral form used by optometrists. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2003;23:21–23.