Chapter 3 Communication

Communication has three key components – verbal communication, non-verbal communication and active listening.

Communication has three key components – verbal communication, non-verbal communication and active listening. Effective communication may be hindered by the environment, language barriers, physiological problems preventing the patient from communicating effectively and psychological issues.

Effective communication may be hindered by the environment, language barriers, physiological problems preventing the patient from communicating effectively and psychological issues. Interprofessional working involves communication between all individuals involved in the care of a patient.

Interprofessional working involves communication between all individuals involved in the care of a patient. Interprofessional working encourages the care of patients from all aspects at all times, enhancing the patients’ perception of their care.

Interprofessional working encourages the care of patients from all aspects at all times, enhancing the patients’ perception of their care.INTRODUCTION

Humans communicate by using language, which may be divided into two separate parts – verbal and non-verbal – performed consciously or unconsciously, each with its own function but often intrinsically bound to the other. Written communication in radiography is primarily the use of investigation request cards and case notes. With the advent of a computerised imaging system there is an increasing reliance on electronic forms of communication.

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

Effective communication significantly improves health outcomes by:

VERBAL COMMUNICATION

The verbal use of words, phrases and sentences includes the prosodic (intonation, rhythm, pausing) and also paralinguistic systems (the vocal utterance of sounds, e.g. ‘mmm’, ‘uh-huh’).1

Within radiography there are many technical terms which patients may not understand; however, it is important for practitioners to be able to convey the information and instructions in a suitable manner. The effectiveness of a practitioner’s communication will depend on the ability to use jargon-free and familiar language with patients.2

NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION

EXAMPLES OF NON-VERBAL BEHAVIOURS

Facial expressions

The face can respond instantaneously, providing immediate feedback to others. This may be useful in certain situations where demonstrating empathy, concern and understanding to your patients is important. However, consider the messages that may be perceived if practitioners display uncontrolled, inappropriate facial expressions when faced with offensive body odours or unexpected, unpleasant visual information in the course of their work.

Emotional expression is under voluntary control and can be artificially manipulated, with the face demonstrating intensification or reduction of the emotion. In reality, trying to distinguish people’s emotions from their facial expressions is often more difficult than we imagine because some people are capable of masking their true emotions. Social and cultural norms may distort expression of emotion (Fig. 3.1).

Eye contact

Eye contact can signal a desire to engage and communicate with another person. Others perceive gaze as a signal that they are liked.

Gestures

Orientation and posture

Remember, when you are positioning for a chest X-ray you are standing behind the patient, so consider what impact this has on the effectiveness of your communication (Fig. 3.2).

Appearance

Consider the uniform you are required to wear: what message does this send about you and your role in the organisation? Uniforms can signal rank and status and carry with them expectations of knowledge, behaviour and experience. You are also representing the organisation whenyou put on your uniform, whatever your role and status within it.

Appearance can convey messages about an individual’s attitude to others. Imagine arriving for work wearing a grubby, creased uniform! An unkempt appearance, dirty hair and nails, together with poor hygiene practices, may give the impression that your patients are not highly regarded or their needs respected (Fig. 3.3). Wearing inappropriate amounts of jewellery, perfume or make-up when you are working in a healthcare context may affect the trust patients place in your ability.

Touch

Touch can communicate the following:

Although it may not be common practice in radiography, it is possible that if you shake hands when introducing yourself to the patient initially you may have ‘broken the touch barrier’ and thismakes further touching behaviour more acceptable to the patient (Fig. 3.4).

Paralanguage

Proximity

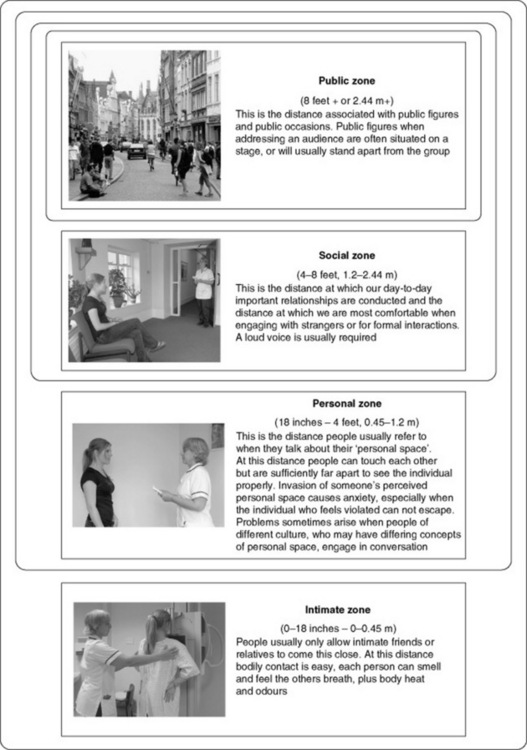

Interpersonal proximity simply means the space between two people. There are four key zones:

As part of radiographic work it is essential to invade the personal space of the patient, even working in the intimate zone at times. Healthcare practitioners are ‘allowed’ to breach these personal space conventions by the nature of their job but this is a privilege which would not normally be permitted. That patients may be embarrassed or nervous may be for no other reason than that their personal space has been invaded (Fig. 3.5).

Listening

Listening is fundamental to everyday basic communication; it is something we all do when we are interested or concerned about a person. One of the highest compliments we can pay to another is to give our full attention by actively listening. Sadly, although a primary skill incommunication, it is probably the least exercised activity!

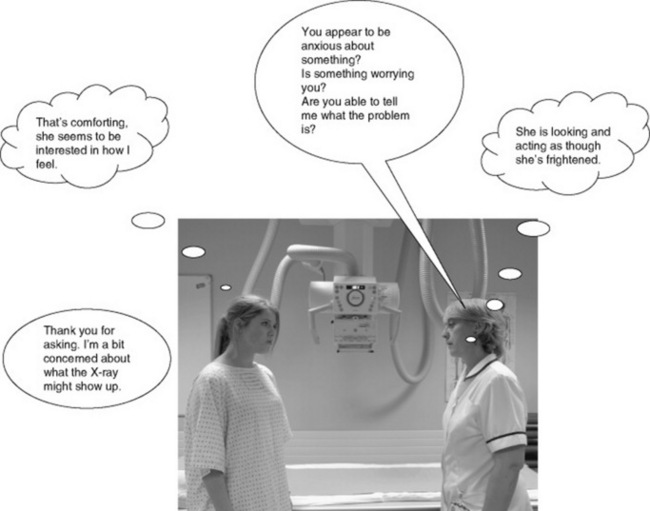

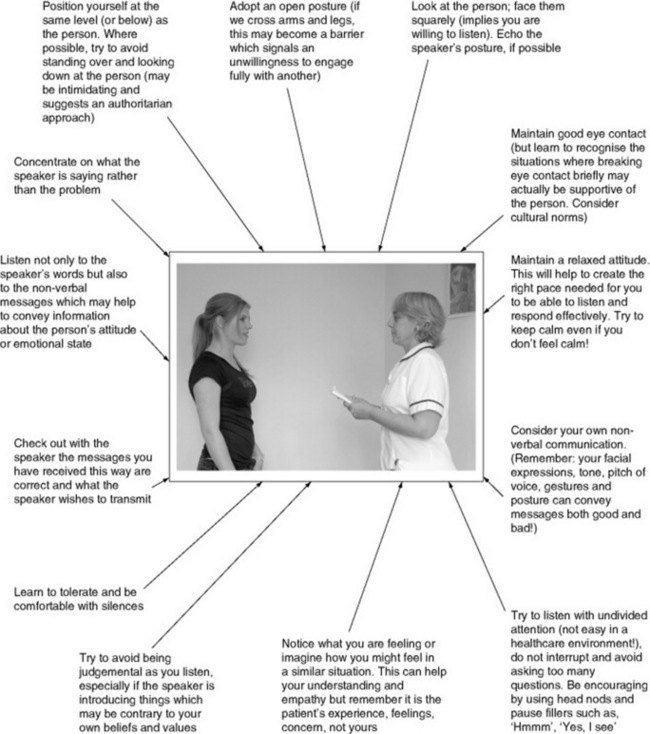

Using ‘active listening’ (Fig. 3.6) and empathy can help your interactions by:

It may also help to reduce your prejudices and stereotypical assumptions about others.

THE PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF VERBAL AND NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION IN DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

The patient’s journey through the department can be divided into three parts:

RECEIVING THE PATIENT

This initial stage of an examination consists of greeting and identifying the patient and conversing in a general manner to put her at ease. A member of the clerical or radiographic staff may carry out the greeting of the patient on entering the department (Fig. 3.7).

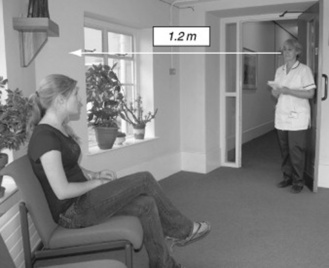

Greeting the patient

It is vital to gain a patient’s trust in the first few interactions; therefore the member of staff should be correctly attired and maintain a social distance whilst establishing eye contact (Fig. 3.8). Remember also, when calling patients from a waiting area, that speaking too close to a person may appear intrusive; too far away can seem very cold, impersonal and unfeeling. The patient should be called by title and family name, for example Mrs. Smith. If there is more than one person with the same name then it may be necessary to use a first name to clarify the patient’s identification. It is important not to shout from the doorway of the X-ray room or down a corridor as this can breach the patient’s confidentiality. It may also be necessary to assist the patient to stand or walk, or she may be in a wheelchair and unable to move independently.

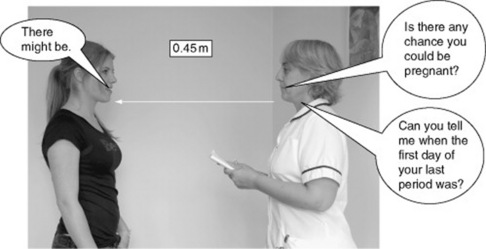

Confidential questioning

Any confidential questions required for identification of the patient (name, age, address) must be asked with due consideration to the patient’s right to privacy, e.g. in a changing cubicle (Fig. 3.9). There are usually signs in the waiting areas to remind female patients that if there is a possibility of pregnancy they should report it to a radiographer. However, to exclude pregnancy, female patients may also need to be asked about their menstrual cycle. The practitioner will now be working within the patient’s ‘personal space’ and should be aware of some people’s anxiety related to this.

Preparing the patient prior to the examination

Asking someone to undress can be embarrassing to members of the opposite sex or different age groups and therefore this must be carried out with sensitivity (Fig. 3.10). The instructions must be precise so that the patient does not get confused and anxious, but should not be delivered in a ‘military style’. Conversely, communicating in a reticent manner can give the impression of unreliability and lack of confidence, which may introduce a barrier to the interaction. The patient must also be given instructions on what to do when ready. It is essential that the patient is not asked to wait in public areas in a state of undress where she may feel uncomfortable.

Preparing the room prior to the examination

Always prepare the X-ray room and equipment prior to carrying out the examination (Fig. 3.11). Consider the nature of the environment in which you work. Although as you become more experienced you may not perceive the technology as being anything other than ‘a means to an end’, for many of your patients their visit may be their only experience of diagnostic imaging. For some, the equipment and procedures can lead to considerable anxiety. Fear of possible pain and of the unknown, as well as apprehension of what the results may reveal, can add to a patient’s stress. Using good observational skills to monitor your patient’s non-verbal behaviours can help determine her needs during the procedure. Pre-procedure information about the investigation is helpful, but supportive interaction between staff and patient during the procedures can facilitate a significant decrease in anxiety levels.

INTERACTING WITH THE PATIENT DURING THE EXAMINATION

A patient entering the X-ray room may find the equipment quite daunting so the practitioner must realise that the patient may not be actively listening to instructions (Fig. 3.12). Therefore, it is essential to use gestures as well as words toindicate what is required. It is also necessary to use plain language and not technical jargon.

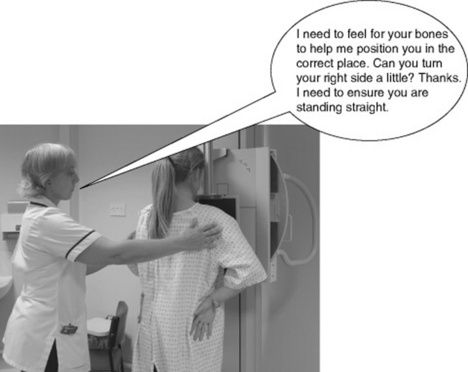

The practitioner will now be working within the ‘intimate zone’ so it is important to fully inform the patient, before commencing the procedure, about exactly what you will need to do in terms of touching her body and what actions are needed from her in order to obtain an optimal image. By inviting the patient to position herself wherever possible, any embarrassment associated with your touch can be reduced (Fig. 3.13).

Positioning the patient it is an ideal opportunity to make her feel at ease with general conversation. During early days of learning clinical skills it is possible that the technical aspects of positioning equipment and patient may overshadow the use of effective communication. Giving clear explanations of what is required is unlikely to take any longer than trying to manipulate an uninformed, rigid, anxious or embarrassed patient into the optimal position for the image capture. The patient may also need instructions on breathing techniques (e.g. halted inspiration/expiration). A practice of the required technique before the exposure often saves errors andpossible repeat images being required due to movement unsharpness.

INSTRUCTING THE PATIENT AFTER THE EXAMINATION

After the examination the patient will be required to wait (possibly remaining in the gown) until the image has been processed and checked for quality and technical suitability. When the checking of the image is complete the patient should be instructed on the process by which they can obtain the results of the examination (Fig. 3.14).

It is not within the remit of a student, assistant practitioner or practitioner to inform the patient of the diagnosis resulting from the image taken. However, the patient will inevitably ask and theresponse to this type of request can be difficult to deal with, especially if you are aware that there was an abnormality on the image. It is advisable to say that you cannot give details because the image will be looked at by a radiologist/reporting radiographer later. Do not feign ignorance of what the image shows because, as the patient will assume you have some knowledge of the human body, she might infer that you are lying. In this instance, your facial expression needs to match what you are saying.

DEALING WITH DIFFICULT OR AGGRESSIVE PATIENTS

The type of ‘welcome’ received by the patient on arrival in the department can defuse potentially difficult situations.3 There are many reasons for escalating aggressive behaviour including:

INTERPROFESSIONAL WORKING

Headrick et al4 suggest the following barriers to interprofessional collaboration:

A multidisciplinary healthcare team is no different to any other group in society. According to Tuckman5 a team passes through various stages (forming, storming and norming) until it reaches a performing stage and a possible phase of adjourning. During the formation there will be the inevitable vying for position and conflict of ideas until the group settles down and performs the required task.

Headrick et al 4 highlight that improvements in health outcome are likely to occur if relevant practitioners (and users) are brought together to share knowledge and experiences as a means to agree what improvements are needed. These agreedgoals can be tested in practice and are more likely to result in measurable improvements for patients than concentrating on what appear on the surface to be irreconcilable professional differences.

Quality teamwork and effective interprofessional collaboration share many characteristics:

1 Ellis A, Beattie G. The psychology of language and communication. Hove, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1986.

2 Minardi H, Riley M. Communication in health care: a skills based approach. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997.

3 Keane P. How to…de-escalate potentially aggressive interactions with patients. Synergy. 2006;Dec:8-10.

4 Headrick LA, Wilcock PM, Batalden PB. Interprofessional working and continuing medical education. BMJ. 1998;316(7133):771-774.

5 Tuckman BW. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol Bull. 1965;63:384-389.