CHAPTER 21 Common surgical procedures of the gastrointestinal tract

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) surgery is a vast topic encompassing many different techniques. These procedures can be performed by the traditional open surgery or more and more commonly laparoscopically (keyhole). Whether surgery is open or laparoscopic, the procedures should remain the same.

Upper gastrointestinal procedures

Cancer surgery

The principle of cancer surgery is to remove the tumor completely with histologically proven margins and the lymph nodes that drain the tumor. Histologically, completeness of tumor clearance from the resection margins is classified R0, R1and R2. An R0 resection is defined as one where all margins are histologically free of tumor. An R1 resection is defined as one in which microscopic residual disease has been left behind. An R2 resection is defined as incomplete resection with macroscopic residual disease.

Esophagectomy

Indication: esophageal cancers and occasionally benign esophageal strictures.

Main blood vessels divided: left gastric artery and esophageal arterial branches.

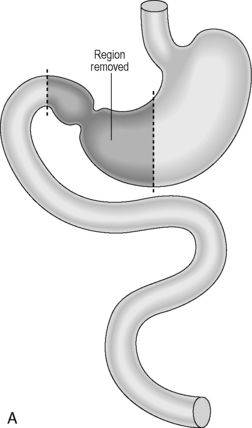

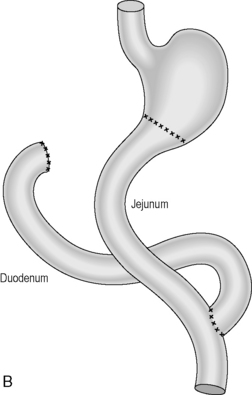

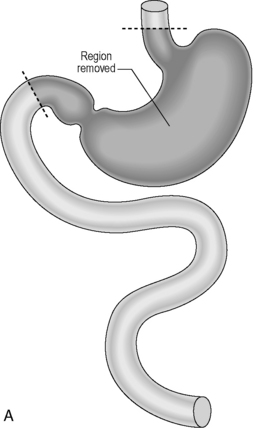

Subtotal gastrectomy

Area resected: the distal half to two thirds of stomach with the surrounding lymph nodes.

Main blood vessels divided: left and right gastric arteries, right gastroepiploic artery.

Reconstruction: historically, the continuity was usually reconstructed by carrying out a simple gastrojejunostomy. This can result in significant biliary reflux which can cause anastomotic ulcerations. A roux-en-Y reconstruction negates biliary reflux and is generally the preferred option of reconstruction (Figures 21.1A, 21.1B).

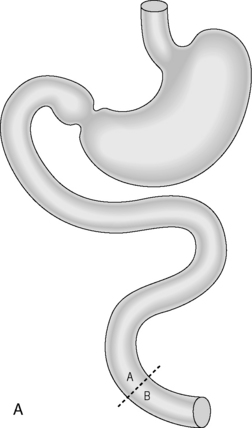

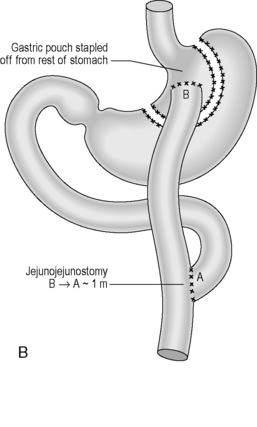

Total gastrectomy

Indication: gastric cancer located in the proximal part or body of the stomach.

Area resected: whole stomach and surrounding lymph nodes.

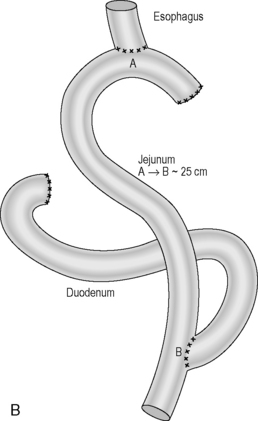

Reconstruction: A roux-en-Y reconstruction with or without a neogastric pouch. This is akin to a J-shaped ileoanal pouch (see ileoanal pouch) (Figures 21.2A, 21.2B and 21.3A, 21.3B).

Figure 21.2 (A) Total gastrectomy, resection margins; (B) total gastrectomy, roux-en-Y reconstruction.

Benign surgery

Antireflux procedures

Indication: Gastro-esophageal reflux disease including repair of hiatus hernia.

Procedure: Performed laparoscopically, this procedure essentially consists of two parts:

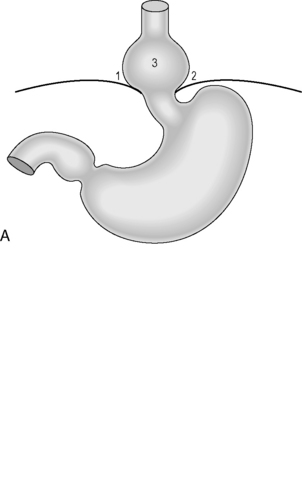

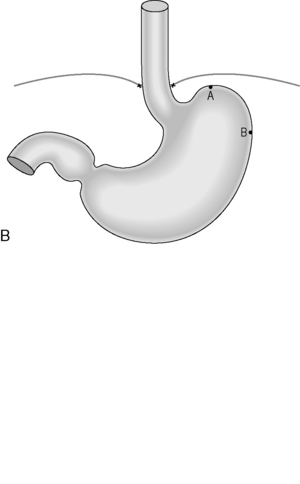

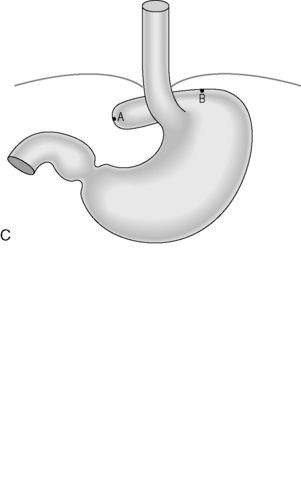

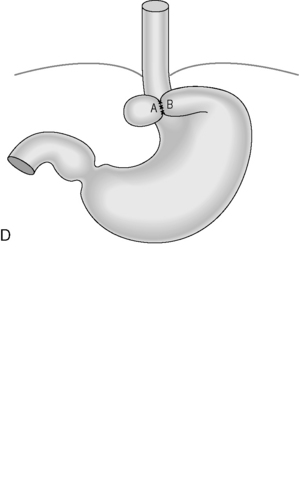

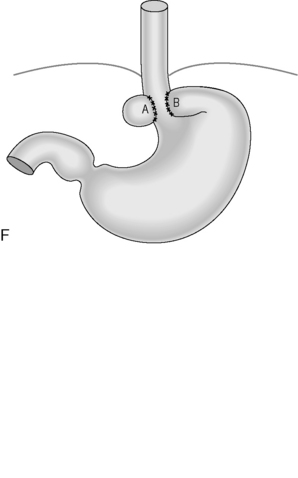

Antireflux surgery has a number of variations; however, the two gold standard procedures were described by the German surgeon Rudolph Nissen (1896–1981) and the French surgeon Andre Toupet born in 1915. Nissen’s fundoplication is a complete (360 degrees) wrap with the fundus round the lower esophagus and Toupet’s fundoplication is one where the fundus wraps the posterior aspect of the lower esophagus, variations suggest between 180 and 270 degrees (Figures 21.4 A–F).

Figure 21.4 (A) Wide diaphragmatic hiatus (1–2), gastric herniation (3); (B) gastric herniation reduced and the hiatus repaired. A retro-esophageal tunnel is created to allow for fundoplication; (C) gastric fundus pulled through to the right of the esophagus; (D) the Nissen 360 degrees wrap created by suturing points ‘A’ and ‘B’; (E) Nissen wrap at barium swallow; (F) the alternative Toupet 270 degrees wrap can be created by suturing points ‘A’ and ‘B’ to the sides of the esophagus.

Main blood vessel divided: the short gastric vessels may be divided.

Heller’s myotomy

Procedure: this procedure is carried out laparoscopically. A longitudinal incision down to but not beyond the mucosa is made in the lower esophagus extending into the gastric cardia. The smooth muscle is parted preventing it from forming a ring when contracted. Many patients will suffer from gastro-esophageal reflux following this and a partial fundoplication is often performed to reduce this.

Surgery to the small bowel

Indication: small bowel strictures, ischemia, small bowel tumors, any small bowel pathology.

Main blood vessels divided: arteries that supply the segment of bowel.

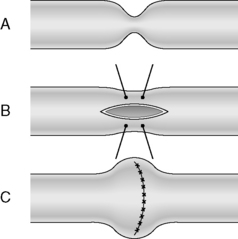

Strictureplasty (Figure 21.5) is of particular value with benign stricturing patient associated with Crohn’s disease, as it preserves small bowel length. Strictureplasty is a technique whereby a narrowed segment(s) of the small bowel (Figure 21.5A) is individually refashioned to widen the lumen. This is achieved by incising the strictured bowel longitudinally (Figure 21.5B) and then suturing the incision transversely (Figure 21.5C).

Bariatric surgery

Indication: treatment of obesity with body mass index above 35.

Lower gastrointestinal procedures

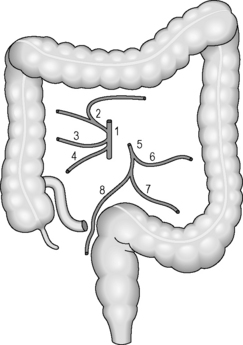

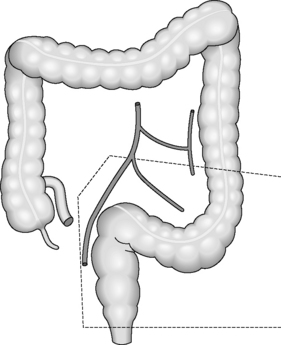

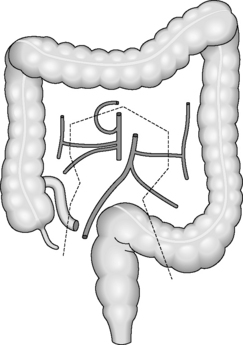

Regardless of the indication for an operation, whether it is for cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, the surgical principles are the same for colorectal surgery. The pathology needs to be removed with a margin of healthy tissue on each side. The segmental resections of the large bowel are based on the blood supply and lymph node drainage. Even if the area of abnormality is small, a whole segment of colon will be removed depending on which blood vessel has to be divided to aid removal (Figure 21.6). This is because if a blood vessel is divided, the segment of bowel that it supplies will become ischemic unless it is removed completely.

This section lists the common surgical procedures of the lower gastro-intestinal tract, the indications for surgery and the postoperative radiological appearances.

Ileocecectomy

Bowel resected: distal ileum (depending on the extent of ileal pathology) and cecal pole.

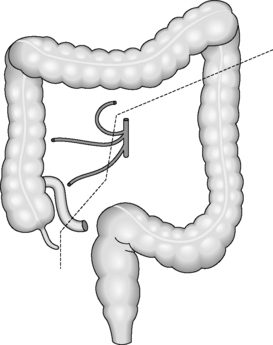

Right hemicolectomy

Bowel resected: last 5–10 cm terminal ileum, cecum, right colon and hepatic flexure.

Blood vessels divided: ileocolic artery, right colic artery ± right branch of middle colic artery (Figure 21.8).

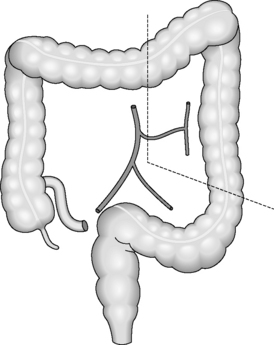

Extended right hemicolectomy

Indication: most commonly a tumor of the mid to distal transverse colon or splenic flexure.

Main blood vessels divided: ileocolic artery, right colic artery, middle colic artery (Figure 21.9).

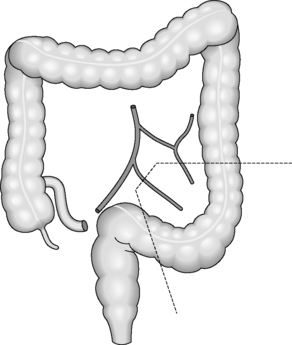

Left hemicolectomy

Bowel resected: distal transverse colon, splenic flexure and descending colon.

Main blood vessel divided: left colic artery (Figure 21.10).

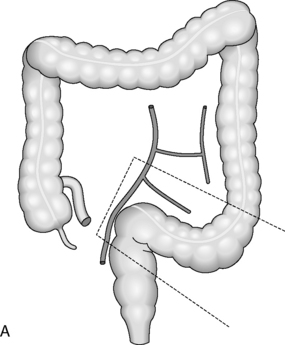

Sigmoid colectomy

Indication: tumor of sigmoid colon, sigmoid diverticular disease, Crohn’s disease or volvulus.

Bowel resected: sigmoid colon.

Main blood vessel divided: sigmoid branch of inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) (Figure 21.11).

Postoperative appearance: this depends on whether the operation was elective or emergency. In the emergency situation, where there may be a lot of fecal contamination, e.g. stercoral perforation (a pressure ulcer that can develop in the colon and lead to a perforation), or perforated sigmoid diverticular disease, a Hartmann’s procedure may be performed. This is where bowel continuity is not restored, the rectal stump is over sewn and the descending colon is brought out as an end colostomy. Occasionally, a track might be deliberately formed from the bowel distal to the defunctioning stoma; this track (a mucus fistula) leads to a second stoma and produces only mucus.

There is little indication for imaging after this procedure. If the procedure was elective or there was no peritoneal fecal contamination, a primary anastomosis will be performed. In this case, postoperative imaging will show a shortened left colon. The sigmoid colon will no longer be present and the left colon will appear less tortuous.

High and low anterior resections

An anterior resection is a resection of the sigmoid and upper rectum.

High anterior resection

Indication: tumor of distal sigmoid colon or upper rectum or severe sigmoid diverticular disease.

Bowel resected: sigmoid colon and upper rectum.

Main blood vessel divided: inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) at its origin (Figure 21.12).

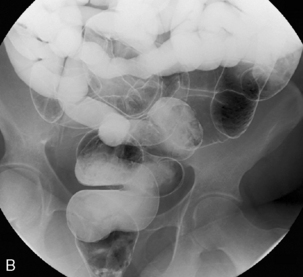

Postoperative appearance: shortened left colon. The sigmoid colon will no longer be present and the left colon will appear less tortuous. A stapled anastomosis is likely and will be seen in the region of the pelvic brim but may be higher or lower depending on rectal anatomy (Figure 21.12B).

With a high anterior resection, it is not necessary to perform a defunctioning loop ileostomy; however, this may be done if there are doubts about the anastomosis. If this is the case, it is usual to perform water-soluble (Gastrografin) enema postoperatively to check the integrity of the anastomosis prior to closing the ileostomy (Figure 21.12C).

Low anterior resection

Indication: mid to low rectal tumor.

Main blood vessel divided: inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) at its origin (Figure 21.13).

Postoperative appearance: shortened left colon. The sigmoid colon will no longer be present and the left colon will appear less tortuous. A stapled anastomosis is almost certain unless a hand-sewn colo-anal anastomosis has been performed and will be seen just above the pelvic floor (Figures 21.14A, 21.14B).

These operations are almost always defunctioned with a loop ileostomy and again it is usual to perform a water-soluble contrast enema postoperatively to check the integrity of the anastomosis prior to stoma closure.

Subtotal colectomy

Bowel resected: distal 5–10 cm of ileum and entire colon to top of rectum.

Main blood vessels divided: ileocolic, right colic, middle colic, left colic, sigmoid arteries (Figure 21.15).

Postoperative appearance: depends on whether bowel continuity has been restored. In the emergency situation, e.g. acute fulminant colitis, an end ileostomy will be fashioned and the rectal stump will remain in situ. There is little indication for imaging postoperatively unless there is doubt about the integrity, health or length of rectal stump. If bowel continuity has been restored, an ileorectal anastomosis will have been performed in which case the ileum will be anastamosed directly to the top of the rectal stump (Figures 21.16A, 21.16B).

Ileoanal pouch

Indication: familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), ulcerative colitis.

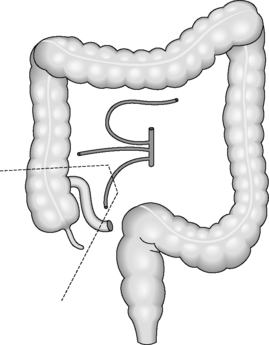

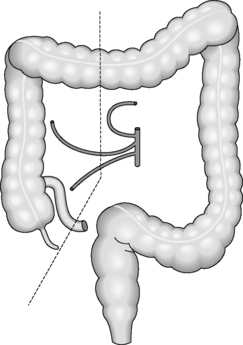

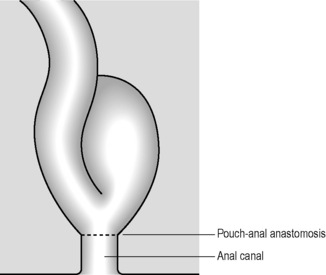

Bowel resected: the entire colon is resected from distal ileum to pelvic floor. In the case of FAP, all colonic mucosa needs to be removed down to the dentate line. In order to restore bowel continuity, the distal ileum is fashioned into a pouch or neo-rectum, which is anastamosed to the top of the anal canal either via a circular stapler or a hand-sewn anastomosis (Figures 21.17, 21.18A, 21.18B and 21.19).

Figure 21.17 Ileoanal pouch. A loop of ileum is looped back on itself in a U-shape and sutured or stapled to form a pouch.

Postoperative appearance: a ring of staples may be seen at the top of the anal canal. The appearance of the pouch depends on its configuration. The commonest type is a stapled J pouch, followed by a hand-sewn W.

Abdominoperineal resection (AP resection, APR, APER)

Bowel resected: accessed via the abdomen and from around the anus, the sigmoid, rectum and anal canal are removed and the descending colon is fashioned into an end colostomy.

Type of anastomosis

Anastomoses can be performed using staplers or hand-sewn with sutures. For distal anastomoses of high or low anterior resections, a circular staple gun is used which fires a ring of staples that can be clearly seen on x-ray (see Figures 21.12B, 21.14A). In the pelvis, circular staplers allow anastomoses to be performed that would be impossible or extremely difficult to perform with sutures.

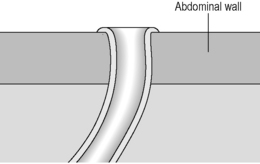

Stomas

A colostomy is usually in the left iliac fossa, contains more solid stool and is flush with the skin (Figure 21.20).

Stomas are performed for various reasons:

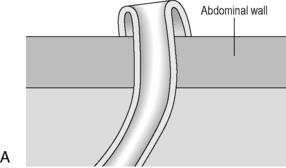

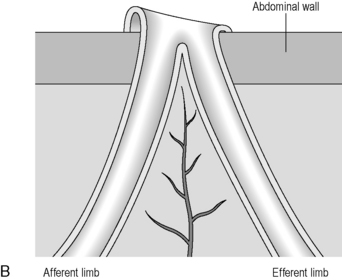

There are loop or end stomas (Figure 21.21A). Temporary defunctioning stomas are almost always loop stomas. It is possible to intubate either limb for imaging. In a loop ileostomy, the spouted end will be proximal (Figure 21.21B); in a loop colostomy, the passage of stool usually indicates which end is proximal. Temporary stomas can be closed any time after 6 weeks, but this depends on the fitness of the patient and integrity of the anastomosis on postoperative imaging.

Laparoscopic colorectal surgery

Laparoscopic surgery is minimally invasive surgery where the bulk of the operating is performed using a laparoscope and laparoscopic instruments, inserted through very small incisions. This replaces traditional surgery, which is performed through a midline or transverse incision. The technique was first perfected with laparoscopic cholecystectomy with the benefits of reduced pain and earlier return to normal activities. However, laparoscopic resection has been slower to evolve as a technique for colorectal cancer surgery because it is technically demanding and time consuming, especially when the surgeon is on a learning curve. Early in its evolution there was concern about a high morbidity of up to 21%, which deterred surgeons from adopting the technique (Berends et al., 1994). The incidence of port site metastases led to concern about cancer outcomes and whether laparoscopic surgery was oncologically equivalent to traditional open surgery.

An early British study (the CLASICC trial) reflected the learning curve of surgeons with conversion rates to open surgery of 29%, but there were no differences in mortality, postoperative complications or the number of positive circumferential resection margins (Guillou et al., 2005). Since then, there have been other randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses which have demonstrated short-term benefits from laparoscopic surgery for colon and rectal cancer in terms of reduced blood loss, less pain, earlier return of bowel function and earlier tolerance of a normal diet. Oncologically, the surgery appears to be equivalent in terms of positive circumferential resection margins for rectal cancer, complete resection for colon cancer and numbers of lymph nodes harvested in the specimen (Breunkink et al., 2006; Wexner and Cera, 2006; Aziz et al., 2006).

Reports of longer-term outcomes suggest similar results for both open and laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer (Reza et al., 2006), but long-term oncological outcomes in terms of local recurrence, disease-free survival and cancer-related mortality are eagerly awaited by the surgical community. There is also expectation that laparoscopic surgery will reduce the rate of postoperative adhesional obstruction and incisional hernia. After initial scepticism, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has now ruled that laparoscopic resection can be recommended as an alternative to open surgery in England and there is wide uptake of the laparoscopic technique within the confines of supervised training (NICE, 2006).

Aziz O., Constantinides V., Tekkis P.P., et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer, a metaanalysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol.. 2006;13(3):413-424.

Berends F.J., Kazemier G., Bonjer H.J., et al. Subcutaneous metastases after laparoscopic colectomy. Lancet. 1994;344:58.

Breunkink S., Pierie J., Wiggers T. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (issue 4):2006. Art No. CD005400; DOI:10.1002/14651858CD005200.pub2

Guillou P.J., Quirke P., Thorpe H., et al. Short term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopically assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial) multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718-1726.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Technology appraisal guidance 105. 2006. Aug 2006 http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp Accessed 10.11.08

Reza M.M., Blasco J.A., Andradas E. Systematic review of laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br. J. Surg.. 2006;938:921-928.

Wexner S., Cera S.M. Laparoscopy for colon cancer. US Gastroenterology Review. 1–6, 2006.

Bauer J.J., Gorfine S.R. Colorectal surgery illustrated: a focused approach. Mosby-Year Book, 1993.

Keighley M.R.B., Fazio V.W., Pemberton J.H. Atlas of colorectal surgery. Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

Pearson F.G., Cooper J.D., Deslauriers J., et al. Esophageal surgery, Second ed. Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

Taylor T.V., Williamson R.C.N., Watson A. Upper digestive surgery, oesophagus, stomach and small intestine. Elsevier Health Sciences, 1999.