5 Common surgical emergencies

Abdominal pain

History

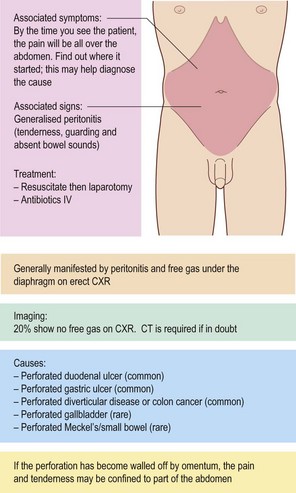

• Onset (especially exactly where the pain started)

• Site, radiation and progression

Examination

Inspection

• Swellings (bulges at site of hernia orifices)

• Scars (beware the scars that are easy to miss, e.g. in the groins, skin creases and loins, laparoscopic scars)

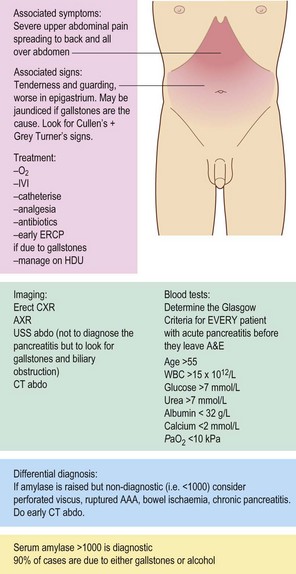

• Discoloration (e.g. bluish colour around umbilicus (Cullen’s sign) or flanks (Grey Turner’s sign) seen in haemorrhagic pancreatitis)

• Visible peristalsis (obstructed bowel)/pulsation (abdominal aortic aneurysm: AAA).

Palpation

• Tenderness (establish area of tenderness and site of maximum severity)

• Guarding (reflex contraction of the abdominal wall in response to palpation)

• Rebound tenderness (exacerbation of pain on sudden release of the palpating hand; care is needed to avoid excessive discomfort)

• Masses (establish site and nature)

• Organs (liver, kidneys and spleen)

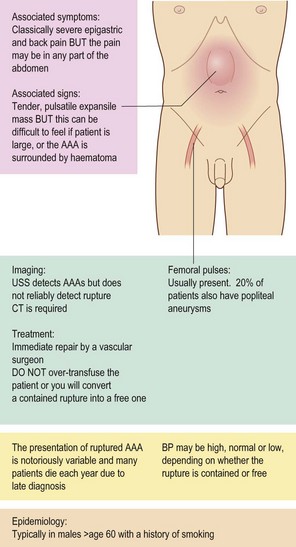

• AAA (felt as a pulsatile, expansile swelling in the epigastrium)

• Check the groins carefully. Strangulated femoral hernias are quite often missed, especially in elderly women with non-specific symptoms

Investigation

Urine

• Urinalysis is vital to exclude diabetes, pregnancy and microscopic haematuria

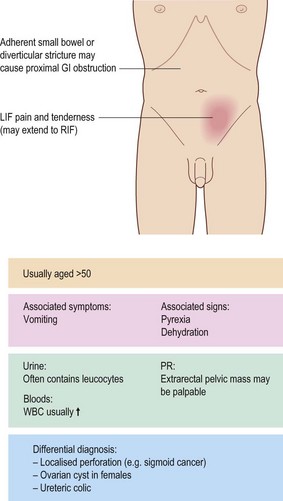

• Any condition causing inflammation in the lower abdomen can cause leucocytes in the urine (e.g. appendicitis and diverticulitis) and this does NOT confirm a urinary tract infection (UTI)

• Bilirubin appears in urine in obstructive jaundice

• Urine microscopy and culture (microscopy may demonstrate numerous organisms in UTI)

Plain X-rays

Box 5.1 The plain AXR in the acute abdomen is full of useful information. It is often helpful to re-examine the abdomen after inspecting the AXR

Gas pattern

CT scanning

When teamed with a good clinical assessment, CT scanning is a tremendously useful examination to diagnose acute abdominal pain. It is sometimes said that a CT scan is unnecessary if there is already an indication for laparotomy. However, CT may render some operations unnecessary (e.g. by confirming terminal malignant disease, or demonstrating acute pancreatitis where perforated duodenal ulceration was expected). Other operations may be made easier by providing useful information preoperatively (Table 5.1). The risk of ionising radiation and contrast exposure must always be weighed against these potential benefits.

| Indication | Advantage of CT |

|---|---|

| Pancreatitis | Demonstrates pancreatic necrosis |

| Aortic aneurysm | CT scanning is the only reliable way to exclude aortic rupture (ultrasound detects aneurysms but does not exclude rupture) |

| Severe or non-resolving diverticulitis | Allows differentiation between localised perforation of diverticulum, diverticular abscess, diverticular mass |

| Large bowel obstruction | Avoids need for water-soluble contrast enema. Usually accurately demonstrates level of obstruction and cause |

| Small bowel obstruction with no hernia or scars | May detect the cause of the obstruction preoperatively |

| Suspicion of malignancy | Acute abdominal pain is common in advanced malignancy. CT scanning may confirm extensive metastatic disease, avoiding laparotomy when palliative care is more appropriate |

| Peritonitis in absence of gas on AXR | CT scanning is very sensitive for small pockets of free gas after perforation of a viscus |

| Acute abdomen | Standard in many hospitals |

Patterns of abdominal pain

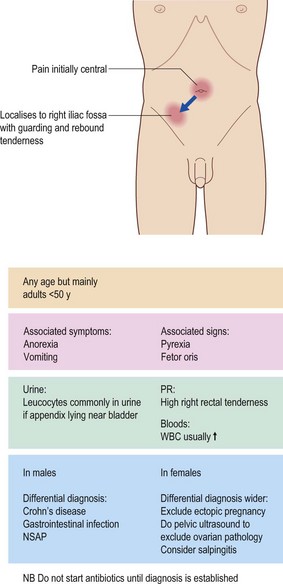

Appendicitis

Pain is initially central, then localises to the right iliac fossa with guarding and rebound tenderness (Fig. 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Symptoms, signs and differential diagnosis of appendicitis. NSAP, non-specific abdominal pain.

Clinical features

Symptoms

If the appendix is lying close to the ureter/bladder then irritative urinary symptoms may result.

Investigations

• AXR is of no value in appendicitis

• The urine often contains leucocytes, but no organisms

• Pregnancy test in females is mandatory to exclude ectopic pregnancy

• Abdominal/pelvic ultrasound may not diagnose appendicitis but usefully rules out ovarian pathology

• In the older patient, CT detects caecal carcinoma and diverticulitis, and reduces normal appendix removals – becoming standard

• Diagnostic laparoscopy in young females is accurate at identifying gynaecological conditions which mimic appendicitis.

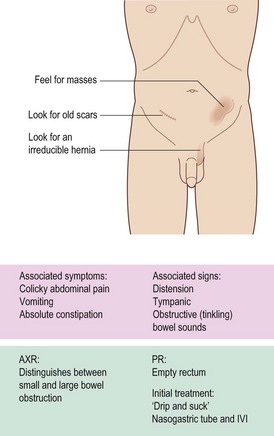

Intestinal obstruction (Fig. 5.2)

Classification and causes

The causes of mechanical obstruction are summarised in Box 5.4. In general, the commonest causes of small bowel obstruction are adhesions or hernia (Table 5.2), and those of large bowel obstruction are colon cancer or diverticular mass.

| Cause | Examination pointers | Requirement for surgery |

|---|---|---|

| Adhesions from previous surgery | Look for the abdominal scar (the surgery may have been many years ago) | Likely to resolve with non-operative treatment |

| Strangulated hernia | Examine hernial orifices carefully: it is easy to miss a small femoral hernia in an obese patient | Unless the hernia can be reduced easily, surgery will be required |

Investigations

Plain abdominal X-rays confirm the diagnosis and distinguish small from large bowel obstruction.

AXR features of small bowel obstruction:

Large bowel obstruction

When a diagnosis of large bowel obstruction is suspected on AXR, the next step is to exclude pseudo-obstruction (Box 5.5) and to determine the site of the obstructing lesion. This requires either water-soluble contrast enema or CT scan.

Non-surgical causes of acute abdominal pain

Urinary retention

Acute urinary retention

A trial without catheter (a ‘TWOC’) is usually attempted after an interval of up to two weeks (often in the urology outpatient clinic), the patient having been given a course of medication aimed at reducing the degree of prostatic hypertrophy. If this is unsuccessful, prostatectomy is usually offered (see p. 252).

Acute limb ischaemia

Lower limb ischaemia

Causes

Management

Immediate action to be taken is outlined in Box 5.6. The next priority is to obtain imaging to determine the cause of the ischaemia and to plan treatment. Duplex ultrasound, magnetic resonance angiography, CT angiography and digital subtraction angiography are all useful; the choice of modality depends on the local facilities available.

Box 5.6 Immediate actions to be taken in the event of acute lower limb ischaemia

Oxygen: at least 24–28% via face mask

Take blood for FBC, baseline coagulation studies, G&S, U&E, glucose

Heparin: give a bolus of 5000 units IV then infuse 1000 units per hour to maintain the APTR at between 2 and 3 (monitor APTR every 6–8 hours and titrate heparin dose)

Rehydration: set up intravenous infusion and catheterise the bladder to monitor fluid balance

Analgesia: morphine 5–10 mg IV with 10 mg metoclopramide

Treat specific co-morbid conditions, e.g. fast atrial fibrillation, cardiac failure or pneumonia

Perianal abscess (see p. 165, 360)

Perianal abscess is the commonest of a number of painful anal conditions which present on the general surgical take (Table 5.3). Examination under anaesthetic is usually required so that sigmoidoscopy (exclude Crohn’s disease) and adequate drainage of the abscess may be performed.

| Condition | Treatment | Page reference |

|---|---|---|

| Perianal abscess | Examination under anaesthesia including sigmoidoscopy, incision and drainage, culture swab, histology of abscess roof | See p. 165, 360 |

| Anal fissure | Trial of medical treatment (glyceryl trinitrate or diltiazem ointment) and/or examination under anaesthesia, injection of botox to internal anal sphincter or lateral sphincterotomy | See p. 164 |

| Thrombosed haemorrhoid | Usually conservative, analgesics, ice and metronidazole, occasionally emergency haemorrhoidectomy | See p. 162 |

| Perianal haematoma | Evacuation under local anaesthetic provides immediate relief | See p. 164 |