Chapter 16 Common Medical and Surgical Conditions Complicating Pregnancy

The more common medical, infectious, and surgical disorders that may complicate pregnancy are covered in this chapter. The pharmacologic agents recommended for these disorders have been classified by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for fetal risk (see Box 7-1 on page 73). Up to date information on these drugs can be found at www.FDA.gov/ by selecting “Drugs” from the menu and searching for a specific agent.

Endocrine Disorders

Endocrine Disorders

DIABETES MELLITUS

Incidence and Classification

GDM is defined as glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy. Pregnancy is associated with progressive insulin resistance. Human placental lactogen, progesterone, prolactin, cortisol, and tumor necrosis factor are associated with increased insulin resistance during pregnancy. Studies suggest that women who develop GDM have chronic insulin resistance and that GDM is a “stress test” for the development of diabetes in later life. Most obstetricians use White’s classification of diabetes during pregnancy. This classification is helpful is assessing disease severity and the likelihood of complications (Table 16-1).

| Class | Description | Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Gestational diabetes; glucose intolerance developing during pregnancy; fasting blood glucose and postprandial plasma glucose normal | Diet alone |

| A2 | Gestational diabetes with fasting plasma glucose >105 mg/dL; or 2-hr postprandial plasma glucose >120 mg/dL, or 1-hr postprandial plasma glucose >140 mg/dL | Diet and insulin |

| B | Overt diabetes developing after age 20 yr and duration < 10 yr | Diet and insulin |

| C | Overt diabetes developing between ages 10 and 19 yr or duration 10-19 yr | Diet and insulin |

| D | Overt diabetes developing before age 10 yr or duration 20 yr or more or background retinopathy | Diet and insulin |

| F | Overt diabetes at any age or duration with nephropathy | Diet and insulin |

| R | Overt diabetes at any age or duration with proliferative retinopathy | Diet and insulin |

| H | Overt diabetes at any age or duration with arteriosclerotic heart disease | Diet and insulin |

Complications

Maternal and fetal complications of diabetes are listed in Table 16-2. Diabetes often coexists with the metabolic syndrome. Most fetal and neonatal effects are attributed to the consequences of maternal hyperglycemia, or, in the more advanced classes, to maternal vascular disease. Glucose crosses the placenta easily by facilitated diffusion, causing fetal hyperglycemia, which stimulates pancreatic β cells and results in fetal hyperinsulinism. Fetal hyperglycemia during the period of embryogenesis is teratogenic. There is a direct correlation between birth defects in diabetic pregnancies and increasing glycosylated hemoglobin levels (HbA1C) in the first trimester. Fetal hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia cause fetal overgrowth and macrosomia, which predisposes to birth trauma, including shoulder dystocia and Erb’s’ palsy. Fetal demise is most likely due to acidosis, hypotension from osmotic dieresis, or hypoxia from increased metabolism coupled with inadequate placental oxygen transfer.

TABLE 16-2 MATERNAL AND FETAL COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES MELLITUS

| Entity | Monitoring |

|---|---|

| MATERNAL COMPLICATIONS | |

| OBSTETRIC COMPLICATIONS | |

| Polyhydramnios | Close prenatal surveillance; blood glucose monitoring, ultrasonography |

| Preeclampsia | Evaluation for signs and symptoms |

| Infections, e.g., urinary tract infection and candidiasis | Urine culture, wet mount, appropriate therapy |

| Cesarean delivery | Blood glucose monitoring, insulin and dietary adjustment to prevent fetal overgrowth |

| Genital trauma | Ultrasonography to detect macrosomia, cesarean delivery for macrosomia |

| DIABETIC EMERGENCIES | |

| Hypoglycemia | Teach signs and symptoms; blood glucose monitoring; insulin and dietary adjustment; check for ketones, blood gases, and electrolytes if glucose > 300 mg/dL |

| Diabetic coma | |

| Ketoacidosis | |

| VASCULAR AND END-ORGAN INVOLVEMENT OR DETERIORATION (IN PATIENTS WITH PREGESTATIONAL DIABETES MELLITUS) | |

| Cardiac | Electrocardiogram first visit and as needed |

| Renal | Renal function studies, first visit and as needed |

| Ophthalmic | Funduscopic evaluation, first visit and as needed |

| Peripheral vascular | Check for ulcers, foot sores; noninvasive Doppler studies as needed |

| NEUROLOGIC | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Neurologic and gastrointestinal consultations as needed |

| Gastrointestinal disturbance | |

| Long-Term Outcome | |

| Type 2 diabetes | Postpartum glucose testing, lifestyle changes (diet and exercise) |

| Metabolic syndrome | Lifestyle changes (diet and exercise) |

| Obesity | Lifestyle changes (diet and exercise) |

| Cardiovascular disease | Annual checkup by physician, lifestyle changes (diet and exercise) |

| Fetal and Neonatal Complications | |

| Maintenance of maternal euglycemia will decrease most of these complications. | |

| Macrosomia with traumatic delivery (shoulder dystocia, Erb’s palsy) | Ultrasonography for estimated fetal weight before delivery; consider cesarean delivery if estimated fetal weight > 4250-4500 g |

| DELAYED ORGAN MATURITY | |

| Pulmonary, hepatic, neurologic, pituitary-thyroid axis; with respiratory distress syndrome, hypocalcemia | Avoid delivery before 39 weeks in the absence of maternal or fetal indications unless amniocentesis indicates lung maturity. Maintain euglycemia intrapartum. |

| CONGENITAL DEFECTS | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | Preconception counseling and glucose control, HbAlc in the first trimester |

| Neural tube defects | Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening; fetal ultrasonography and fetal echocardiogram; amniocentesis and genetic counseling |

| Caudal regression syndrome | |

| Other defects, e.g., renal | |

| FETAL COMPROMISE | |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | Serial ultrasonography for fetal growth and estimated fetal weight, serial fetal surveillance with nonstress test, amniotic fluid index, and fetal Doppler. Avoid postdates pregnancy. |

| Intrauterine fetal death | |

| Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns | |

Diagnosis

An abnormal screening GCT is followed with a diagnostic 3-hour 100-g oral glucose tolerance test. This involves checking the fasting blood glucose after an overnight fast, drinking a 100-g glucose drink, and checking glucose levels hourly for 3 hours. If there are two or more abnormal values on the 3-hour GTT, the patient is diagnosed with GDM (Table 16-3). If the 1-hour screening (50-g oral glucose) plasma glucose exceeds 200 mg/dL, a glucose tolerance test is not required and may dangerously elevate blood glucose values.

| Test | Maximal Normal Blood Glucose (mg/dL) |

|---|---|

| Fasting | 95 |

| 1 hr | 180 |

| 2 hr | 155 |

| 3 hr | 140 |

From Carpenter and Coustan.

Management

THERAPY.

Insulin use is the gold standard to maintain euglycemia in pregnancy. The peak action of lispro insulin is at 30 to 90 minutes, of regular insulin at 2 to 3 hours, and of NPH insulin at 6 to 10 hours. A combination of rapid-acting or short-acting (lispro or regular) and intermediate-acting (NPH) insulin is usually given in split morning and evening doses or more frequently to achieve euglycemia. A method for calculating insulin dosage is shown in Box 16-1.

THYROID DISEASES

Normal Thyroid Physiology during Pregnancy

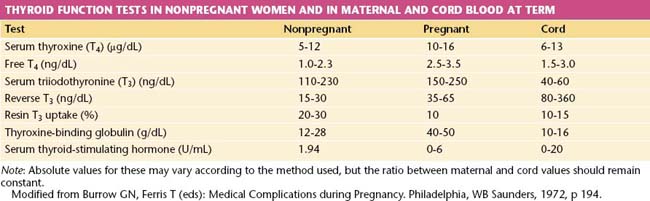

THYROID FUNCTION TESTS.

The free thyroxine (free T4) concentration is the only accurate method of estimating thyroid function that compensates for changes in thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) capacity because serum levels of bound triiodothyronine (total T3) and total T4 are increased during pregnancy. Values of thyroid function tests during pregnancy are shown in Table 16-4.

Heart Disease

Heart Disease

MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC DISEASE DURING PREGNANCY

The New York Heart Association’s functional classification of heart disease is of value in assessing the risk for pregnancy in a patient with acquired cardiac disease and in determining the optimal management during pregnancy, labor, and delivery (Table 16-5). In general, the maternal and fetal risks for patients with class I and II disease are small, whereas risks are greatly increased with class III and IV disease or if there is cyanosis. However, the type of defect is important as well. Mitral stenosis and aortic stenosis carry a higher risk for decompensation than do regurgitant lesions. Other patients at high risk include those with significant pulmonary hypertension, a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%, Marfan syndrome, a mechanical valve, or a previous history of a cardiac event or arrhythmia.

TABLE 16-5 NEW YORK HEART ASSOCIATION’S FUNCTIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF HEART DISEASE

| Class I | No signs or symptoms of cardiac decompensation |

| Class II | No symptoms at rest, but minor limitation of physical activity |

| Class III | No symptoms at rest, but marked limitation of physical activity |

| Class IV | Symptoms present at rest, discomfort increased with any kind of physical activity |

Autoimmune Disease in Pregnancy

Autoimmune Disease in Pregnancy

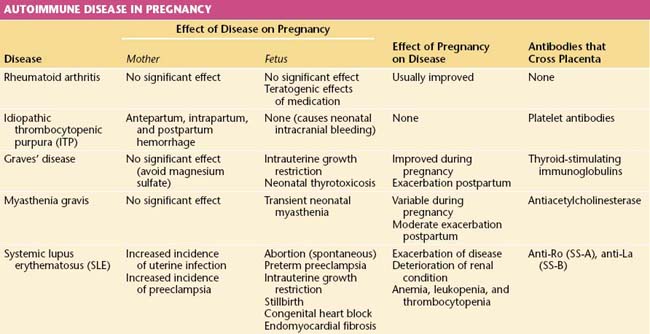

An autoimmune disease is one in which antibodies are developed against the host’s own tissues. A summary of the interactions of primary immunologic disorders and pregnancy is shown in Table 16-6.

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Lupus occurs mainly in women. Associated antibodies include antinuclear, anti-RNP and anti-SM antibodies; anti-dsDNA is associated with nephritis and lupus activity; anti-Ro (SS-A) and anti-La (SS-B) are present in Sjögren’s syndrome and neonatal lupus with heart block; while antihistone antibody is common in drug-induced lupus. The diagnosis of systemic lupus is made if 4 or more of the 11 revised criteria of the American Rheumatism Association are present, serially or simultaneously (Table 16-7).

TABLE 16-7 AMERICAN RHEUMATISM ASSOCIATION 1997 REVISED CRITERIA FOR SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

| Criteria∗ | Comments |

|---|---|

| Malar rash | Malar erythema |

| Discoid rash | Erythematous patches, scaling, follicular plugging |

| Photosensitivity | |

| Oral ulcers | Usually painless |

| Arthritis | Nonerosive involving two or more peripheral joints |

| Serositis | Pleuritis or pericarditis |

| Renal disorder | Proteinuria > 0.5 g/day or > 3+ dipstick, or cellular casts |

| Neurologic disorders | Seizures or psychosis without other cause |

| Hematologic disorders | Hemolytic anemia, leukopenia, lymphopenia, or thrombocytopenia |

| Immunologic disorders | Anti-dsDNA or anti-Sm antibodies, or false-positive VDRL, immunoglobulin M or G anticardiolipin antibodies, or lupus anticoagulant |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Abnormal titer of antinuclear antibodies |

VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

∗ If four criteria are present at any time during course of disease, systemic lupus can be diagnosed with 98% specificity and 97% sensitivity.

From Hochberg MC: Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40(9):1725, 1997. Copyright 1997 American College of Rheumatology. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Renal Disorders

Renal Disorders

ACUTE RENAL FAILURE

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Hepatic Disorders

Hepatic Disorders

Liver disorders that are peculiar to pregnancy are discussed next.

Thromboembolic Disorders

Thromboembolic Disorders

DEEP VENOUS THROMBOSIS

INVESTIGATIONS

Compression ultrasonography with Doppler flow studies is a noninvasive technique that has high sensitivity and specificity and is currently the primary mode of diagnosis used for DVT. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to evaluate patients suspected of having pelvic thrombosis with a negative Doppler ultrasonic examination. D-Dimers can be used in nonpregnant women to screen for DVT, but their use in pregnancy is unproved. The most reliable test for deep venous (noniliac) thrombosis is a well-performed venogram, but this is not generally performed because of the 2% risk for dye-induced phlebitis and radiation exposure, the latter dosage being between 0.05 and 0.628 Gy (see Table 16-8 on page 216).

Obstructive Lung Disease

Obstructive Lung Disease

Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Other Infectious Diseases

Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Other Infectious Diseases

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

Vertical Transmission

In the United States, breastfeeding is not recommended and should be discouraged.

RUBELLA (GERMAN MEASLES)

Impact on Pregnancy

The disease course is unaltered by pregnancy, and the mother may or may not exhibit the full clinical disease. The severity of the mother’s illness does not have an impact on the risk for fetal infection. Rather, it is the trimester in which infection occurs that has the greatest impact on fetal risk. Infection in the first trimester carries up to 80% risk for development of CRS, whereas the risk for CRS drops to 30% to 50% later in pregnancy. CRS rarely occurs after 20 weeks of gestation. Components of CRS are outlined in Box 16-2.

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

Impact on Pregnancy

About 10% to 15% of infected infants are symptomatic at birth, exhibiting nonimmune hydrops, symmetrical IUGR, chorioretinitis, microcephaly, cerebral calcifications, hepatosplenomegaly, and hydrocephaly. About 80% to 90% are asymptomatic at birth but may later exhibit mental retardation, visual impairment, progressive hearing loss, and delayed psychomotor development (Box 16-3). Sensorineural hearing loss is the most frequent sequel of congenital CMV infection and is observed in 40% to 50% of symptomatic children. Recurrent CMV infection is associated with a much lower fetal risk, with a 0.15% to 1% maternal-fetal transmission rate. Few cases of severely affected infants have been reported.

HEPATITIS B AND C VIRUSES

Impact on Pregnancy

The incidence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity (chronic carrier state) in pregnancy in the United States is 6 to 10 per 1000 pregnancies. Women who are asymptomatic HBsAg carriers are at no higher risk for antepartum complications than are the general population. However, newborns delivered to mothers positive for HBsAg have a 10% risk for developing acute infection at birth. This is in contrast to those delivered to mothers positive for both HBsAg and hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg), in which the infant’s risk increases to 70% to 90%. Infection in the infant may be fulminant and lethal. If the infant survives, it has an 85% to 90% chance of becoming a chronic hepatitis carrier and a 25% chance of developing liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, or both. Therefore, it is recommended that all pregnant women be screened for HBsAg carriage during pregnancy. Women in high-risk groups (Box 16-4) should be rescreened in the third trimester if the initial screen is negative.

Bacterial Infections

Bacterial Infections

Parasitic Infections

Parasitic Infections

TOXOPLASMOSIS

Impact on Pregnancy

The incidence of primary infection in pregnancy is 1 in 1000. In immunocompromised women such as those with AIDS, a reactivation of toxoplasmosis could occur that would potentially be associated with a risk for fetal infection. The risk for transmission to the fetus is 15% in the first trimester, 25% in the second trimester, and 65% in the third trimester. However, the severity of fetal infection is greatest with first-trimester infection, and congenital defects are rarely seen if the infection occurs after 20 weeks of gestation. About 15% of infants with congenital infection are symptomatic at birth. A classic triad of hydrocephalus, intracranial calcifications, and chorioretinitis is described. Of the asymptomatic infants, 25% and 50% exhibit later sequelae (Box 16-5).

Surgical Conditions during Pregnancy

Surgical Conditions during Pregnancy

ACUTE CONDITIONS

Appendicitis

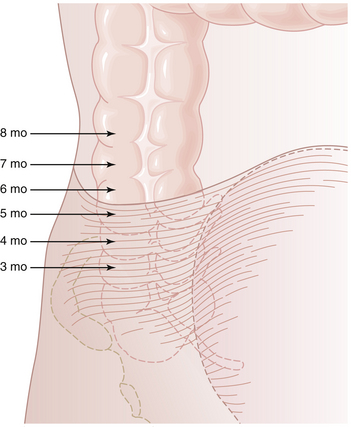

Appendectomy for presumed acute appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency during pregnancy. The incidence of acute appendicitis in pregnancy is about 0.05% to 0.1%, and it is constant throughout the three trimesters. The usual symptoms of acute appendicitis, such as epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and lower abdominal pain, may be less apparent during pregnancy, although right lower quadrant pain is still the most common presentation. The differential diagnosis may be especially confusing (Box 16-6). The enlarging uterus displaces the appendix superiorly and laterally as pregnancy progresses (Figure 16-1). Tenderness and guarding are elicited more laterally than expected. The increased white blood cell count seen in normal pregnancy further confuses the issue. Surgery may be delayed, resulting in an increased rate of rupture, premature labor, infant morbidity, and, rarely, maternal death.

FIGURE 16-1 The changing position of the right colon and appendix as pregnancy progresses and the uterus enlarges.

Imaging studies can increase the accuracy of the diagnosis of appendicitis. The American College of Radiology recommends nonionizing radiation techniques such as ultrasonography and MRI for imaging in pregnant women. On ultrasound, the abnormal appendix can be visualized as a noncompressible tubular structure measuring 6 mm or greater in the region of the patient’s pain. Helical computed tomography has the disadvantage of radiation exposure, but appendicitis is suspected if right lower quadrant inflammation, an enlarged nonfilling tubular structure, or a fecalith is noted. The estimated fetal radiation exposure is about 250 mrad. Exposure to less than 5 rad (0.05 Gy) has not been associated with an increase in fetal anomalies or pregnancy loss. Table 16-8 shows the dose of ionizing radiation to the fetus from common diagnostic radiologic procedures.

TABLE 16-8 ESTIMATED FETAL EXPOSURE FROM SOME COMMON RADIOLOGIC PROCEDURES

| Procedure | Fetal Exposure∗ |

|---|---|

| Chest radiograph (two views) | 0.02-0.07 mrad |

| Abdominal film (single view) | 100 mrad |

| Intravenous pyelography | >1 rad† |

| Hip film (single view) | 200 mrad |

| Mammography | 7-20 mrad |

| Barium enema or small bowel series | 2-4 rad |

| CT scan of head or chest | <1 rad |

| CT scan of abdomen and lumbar spine | 3.5 rad |

| CT pelvimetry | 250 mrad |

† Exposure depends on the number of films.

Data from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 299. Obstet Gynecol 104:649, 2004.

If acute appendicitis is diagnosed, laparotomy with appendectomy should be carried out. A McBurney, transverse, or Rockey-Davis incision can be employed. Laparoscopic appendectomy may increase the risk for fetal loss. A potential concern is that carbon dioxide used for insufflation can be absorbed across the peritoneum into the maternal bloodstream and across the placenta, leading to fetal respiratory acidosis and hypercapnia. As gestation progresses, the likelihood increases that the pneumoperitoneum will decrease venous return, cardiac output, and uteroplacental blood flow. Laparoscopic appendectomy may be considered if specific recommendations are met (Table 16-9).

TABLE 16-9 SAGES GUIDELINES FOR LAPAROSCOPIC OPERATIONS DURING PREGNANCY AND PROPOSED GUIDELINES TO IMPROVE SAFETY OF THE PROCEDURE

| SAGES Guidelines | Moreno-Sanz’s Proposed Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Pneumatic compression devices | Same recommendation |

| Open abdominal access (Hasson) | Same recommendation |

| Pneumoperitoneum pressure ≤12 mm Hg∗ | Same recommendation |

| No routine prophylactic tocolytic therapy | Same recommendation |

| Obstetric consultation should be obtained preoperatively | Preoperative and postoperative obstetric consultation should be obtained∗ |

| Continuous intraoperative fetal monitoring | Preoperative and postoperative ultrasonographic examination and cardiotocography∗ |

| Maternal end-tidal CO2 and/or arterial blood gases should be monitored | Maternal intraoperative end-tidal CO2 monitoring (30-40 mm Hg)∗ |

| Routine venous thrombosis prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin† | |

| Use of harmonic scissors† |

SAGES, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons.

From Moreno-Sanz CJ: Laparoscopic appendectomy during pregnancy: Between personal experiences and scientific evidence. Am Coll Surg 205:37-42, 2007.

Abalovich M., Amino N., Barbour L.A., et al. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:s1-s47.

McKay D.B., Josephson M.A. Pregnancy in recipients of solid organs—effects on mother and child. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1281-1293.

Perkins J., Dunn J., Jagasia S. Perspectives in gestational diabetes mellitus: A review of screening, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Diabetes. 2007;25:57-62.

Saleh M.M., Abdo K.R. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Review of the literature and evaluation of current evidence. J Womens Health. 2007;16:833-841.

Sulenik-Halevy R., Ellis M., Fejgin S. Management of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:182-188.

Seizures

Seizures