Chapter 44 Common cutaneous malignancies

| MALIGNANCY | CELL OF ORIGIN |

|---|---|

| Premalignancies (in situ) | |

| Actinic keratosis | Keratinocyte |

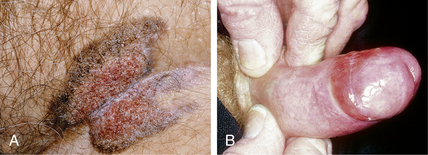

| Squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease) | Keratinocyte |

| Malignant melanoma in situ | Melanocyte |

| Lentigo maligna (Hutchinson’s freckle) | Melanocyte |

| Common Cutaneous Malignancies | |

| Basal cell carcinoma | Follicular keratinocyte origin (probable) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Epidermal keratinocyte |

| Keratoacanthoma | Follicular keratinocyte |

| Melanomas | |

| Malignant melanoma | Melanocyte |

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | Melanocyte |

| Uncommon Cutaneous Epithelial Malignancies | |

| Sweat gland carcinoma (numerous variants) | Apocrine or eccrine sweat gland/duct |

| Follicular carcinomas (several variants) | Follicular epithelial cells |

| Extramammary Paget’s disease | Modified keratinocytes (Toker cell) |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | Neuroendocrine cell |

| Cutaneous Mesenchymal Malignancies | |

| Atypical fibroxanthoma | Fibroblast |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | CD34+ dermal dendrocyte |

| Fibrosarcoma | Fibroblast |

| Angiosarcoma | Endothelial cell |

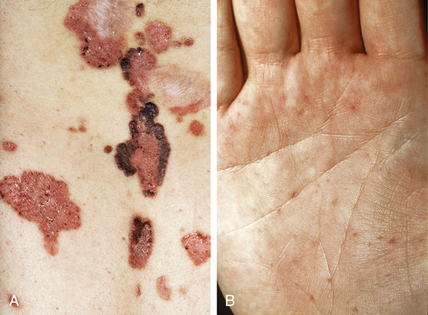

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | Endothelial cell |

| Hemangiopericytoma | Pericyte |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors | Schwann cells |

| Liposarcoma | Lipocyte |

Diepgen TL, Mahler V: The epidemiology of skin cancer, Br J Dermatol 146:1–6, 2002.

Nguyen TH, Ho DQ: Nonmelanoma skin cancer, Curr Treat Options Oncol 3:193–203, 2002.

Honda K: HIV and skin cancer, Dermatol Clin 24:521–530, 2006.

Table 44-2. Management of Cutaneous Premalignancies and Malignancies

| LESION | TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| Actinic keratosis | Cryosurgery Curettage Fluorouracil, topical Chemical peel Dermabrasion Imiquimod Photodynamic therapy |

| Actinic cheilitis | Cryosurgery Electrosurgery Chemical peel Laser ablation Lip shave and advancement Imiquimod |

| Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) | |

| Superficial spreading | Cryosurgery Curettage ± electrosurgery Laser ablation Imiquimod Photodynamic therapy |

| Nodular BCC | Cryosurgery Curettage and electrosurgery Excision Radiation therapy Photodynamic therapy Mohs surgery |

| Morpheaform, aggressive BCC, or recurrent BCC | Excision Mohs surgery |

| Nonresectable BCC | Cryosurgery Radiation therapy Chemotherapy |

| Keratoacanthoma | Deep shave plus curettage Curettage plus electrosurgery Intralesional 5-fluorouracil Cryosurgery Excision Mohs surgery |

| SCC in situ (Bowen’s disease) | Curettage ± electrosurgery Fluorouracil, topical Imiquimod Cryosurgery Laser Excision Photodynamic therapy |

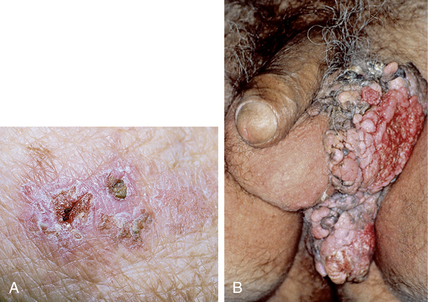

| Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) | |

| Small, nonaggressive | Curettage plus electrosurgery Cryosurgery Excision |

| Large or aggressive | Excision Mohs surgery Radiation therapy Lymph node dissection |

| Nonresectable SCC | Radiation Chemotherapy |

Neville J, Welch E, Leffell D: Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer in 2007, Nat Clin Pract Oncol 4:462–469, 2007.

Epstein EH: Basal cell carcinomas: attack of the hedgehog, Nat Rev Cancer 8(10):743–754, 2008.

Basal cell carcinomas can also be completely or focally pigmented and mistaken for malignant melanoma. A rare variant of BCC looks like a large skin tag or fibroma. This variant is usually found on the trunk of older men and is called a Pinkus tumor or fibroepithelioma of Pinkus.

High A, Zedan W: Basal cell nevus syndrome, Curr Opin Oncol 17:160–166, 2005.

Rudolph R, Zelac DE: Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, Plast Reconstr Surg 114:82e–94e, 2004.

Karaa A: Keratoacanthoma: a tumor in search of a classification, Int J Dermatol 46:671–678, 2007.

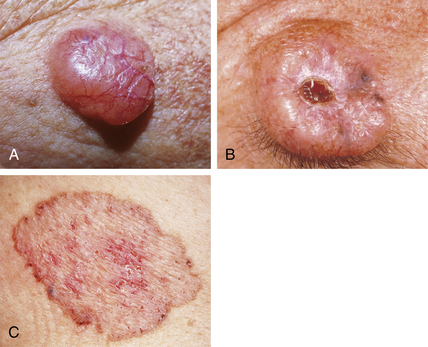

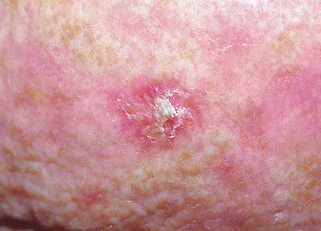

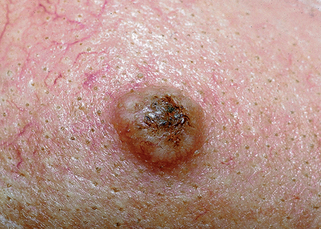

Figure 44-4. Keratoacanthoma demonstrating a crateriform nodule with central keratin plug.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)