22 Combination treatment

Summary and Key Features

• Aging in the face is not simply defined by the appearance of wrinkles

• Treatments targeting superficial rhytides do not address the underlying loss of volume or changes in skin texture or pigmentation

• A three-dimensional approach to facial augmentation must consider the interaction and influence of adjacent areas

• Multiple modalities may be required for optimal outcomes

• Current approaches to rejuvenation combine augmentation and contouring with movement control

• Augmentation of entire regions may eliminate the need for additional procedures

• Lasers and light-based therapies improve pigmentation and texture of the skin

• The popularity of surgical procedures has declined with the availability of less-invasive options

• BoNT enhances the outcome of soft tissue augmentation, resurfacing, and surgical procedures

• Concomitant BoNT extends the duration of the filling agent and improves cosmetic appearance

• Used in combination with resurfacing, BoNT promotes better healing of newly remodeled skin

• Chemodenervation targets dynamic rhytides and immobilizes musculature underlying or surrounding a wound or surgical incision

• Immobilization of musculature promotes healing and prevents dehiscence, particularly for wounds or scars that lie in an area of great mobility

• Reduced muscular activity during the healing process leads to superior cosmesis

Soft tissue augmentation

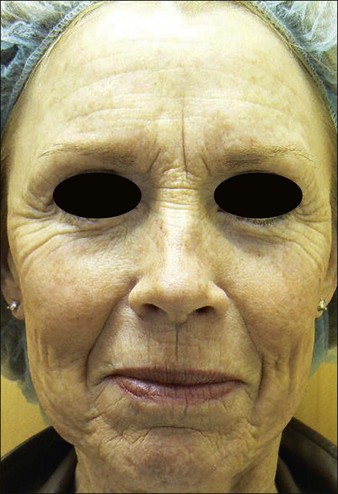

In the last few years, clinicians have gained a greater appreciation for the three-dimensional approach to facial rejuvenation. Treating the surface of the skin – the lines and wrinkles that emerge over time – does not address the volume loss that characterizes the aging process. Volume loss in the glabella and forehead may combine with brow and eyelid ptosis and reduced lateral brow projection (Fig. 22.1). Repetitive movements of facial expression, loss of bone, and thinning of the skin due to photodamage all exacerbate this age-related fat depletion. Loss of support from underlying bony structures and tissue causes skin to sag and reposition over the changing contours of the face.

Figure 22.1 The aging face is characterized by loss of volume, bony changes, thinning skin, and rhytides and folds.

Current approaches to facial rejuvenation combine augmentation and contouring with movement control, using BoNT in combination with HA fillers to achieve results that are longer lasting and more satisfying in resting glabellar rhytides, brow-height adjustment, horizontal forehead lines, nasojugal folds, sculpting the zygomatic and perioral regions, and to improve the appearance of the neck (Table 22.1). Pre-treatment with BoNT serves to reduce the dynamic component of the target rhytide, which may allow more accurate estimation of the volume of filler needed and preventing overcorrection. Moreover, chemodenervation may increase the longevity of the implant by reducing microextrusion caused by repetitive muscular motion.

| Filling agents | Indications for combination therapy | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic acid |

A number of studies have shown superior efficacy and patient satisfaction associated with combination therapy compared to fillers alone, particularly in individuals with deep resting rhytides. In 2003, Carruthers and colleagues compared the efficacy of BoNT alone or in combination with hyaluronic acid (HA) in 16 patients with moderate-to-severe resting glabellar rhytides via retrospective analysis. Response to the filling agent plus chemodenervation was compared clinically and photographically to the response to BoNT alone. In 94% of patients receiving combination therapy, severity of rhytides decreased from moderate or severe to mild. By contrast, patients receiving BoNT alone experienced only moderate success. To further examine the relationship between chemodenervation and filling agents, Carruthers and Carruthers conducted a randomized trial of 38 patients with moderate-to-severe glabellar rhytides receiving HA alone or in combination with BoNT; the latter group showed a better response both at rest and on maximum frown (Fig. 22.2). The addition of BoNT also extended the duration of the filling agent, from 18 weeks for HA alone, to 32 weeks for combination therapy. Patel and colleagues found improved clinical effects of longer duration and greater patient satisfaction in 65 subjects who received BoNT and collagen for the treatment of glabellar rhytides compared to patients who received either modality alone. In 2010, Carruthers and colleagues demonstrated similar results in a multicenter, randomized trial of 90 women treated with BoNT, HA, or in combination for rejuvenation of the perioral area and lower face. Combination therapy was superior to either modality used alone (Fig. 22.3).

Although initially considered treatment for only deeper folds and rhytides, combination treatment with toxins and fillers is considered the standard regimen for facial rejuvenation in many cosmetic offices, with a greater emphasis on augmentation. This shift comes, in part, from a greater understanding of the three-dimensional nature of aging, particularly loss of volume from and bone remodeling in the malar and zygomatic regions, brow, and infraorbital hollow. Moreover, clinicians take a more holistic approach, considering not only the treatment of targeted rhytides and folds, but also their interaction with adjacent regions and the influence of augmentation on the appearance of the face as a whole. Volumizing the glabella and medial forehead, for example, can lift the brow, soften forehead lines, elevate the root of the nose, and lessen horizontal procerus rhytides (Fig. 22.4). The authors (JC and AC) use fillers increasingly to layer in a smooth, thin sheet of filler throughout entire regions (i.e. the forehead, upper lip, sides of the chin and anterior cheeks), lessening the need for other modalities.

Lasers and light-based therapies

Lasers – including broadband light and radiofrequency devices – have become an indispensable part of the cosmetic surgeon’s armamentarium in combating photoaging (Table 22.2). Concomitant use of BoNT and these devices leads to optimal improvement of dynamic rhytides, superior and longer-lasting outcomes, better healing of newly remodeled skin, and a more permanent eradication of wrinkles.

Table 22.2 Lasers and light-based therapies with adjuvant BoNT

| Lasers / light-based therapies | Indications for combination therapy | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Ablative |

Non-ablative light sources

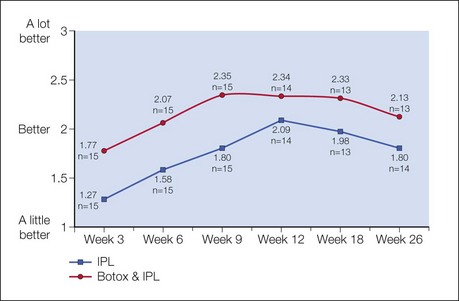

Carruthers & Carruthers compared IPL alone or in combination with BoNT for the treatment of the periorbital area. Patients who received both modalities experienced a 15% improvement in overall aesthetic benefit at the 6-month evaluation (Fig. 22.5). Remarkably, the overall improvement in wrinkling, texture, and blemishes in the combined treatment group exceeded those of the IPL-only group more than 6 months after BoNT, far longer than the expected duration of its direct effect. The noted improvements in telangiectasias underscore the ability of BoNT to regulate blood vessel constriction and treat persistent facial flushing. Although the complete mechanism of action is not fully understood, this enhancement may be partially due to the denervating effect of BoNT, which prevents the active muscular disturbance of newly deposited dermal collagen. Similarly, Khoury and colleagues evaluated small wrinkles and fine lines, erythema, hyperpigmentation, pore size, skin texture, and overall appearance for 8 weeks in a randomized, split-face study in which patients were treated with BoNT or saline plus IPL. Adjunctive BoNT achieved a greater degree of improvement in small wrinkles and fine lines and erythema.

Aesthetic surgery

As a result of the increasing demand for non-invasive, injection-based facial rejuvenation, the number of surgical procedures in cosmetic dermatology has declined. However, some patients – such as those with excessive lower eyelid fat, for example – cannot be treated adequately with BoNT, fillers, or resurfacing alone and require surgical intervention. In many surgical approaches in the head and neck, underlying muscular action can reverse the intended surgical outcome, and therefore results may be short-lived. Chemodenervation is a strong partner and key adjunct to many aesthetic surgeries (Table 22.3). Pre- and post-treatment injections aid in stabilizing musculature while procedures heal (reducing repetitive muscular actions and thus the rate of dehiscence), improving outcomes and longevity of the procedure and circumventing complications, particularly for brow lift, blepharoplasty, and facelift.

| Surgical procedures | Outcomes |

|---|---|

Wound healing and scars

Injection of BoNT prior to surgical procedures or into the muscles underlying or surrounding a sutured wound has shown to improve cosmesis and aid in the healing process (Table 22.4). Because the major factor influencing the final appearance of a scar is the tension exerted on the edges of the wound in the healing stage, wound immobilization is a basic therapeutic principle in plastic surgery. Surgical techniques for immobilization can only reduce – not eliminate – such tension. As a result, continuous muscle activity surrounding a wound leads to a prolonged inflammatory response and hypertrophic and hyperpigmented scars. Pre-treatment of the underlying muscles in surgical procedures allows surgeons to use finer sutures and achieve better cosmesis. Animal and human studies have shown that immobilization with BoNT in the muscles surrounding or underlying a sutured wound can improve the cosmetic appearance of cutaneous scars by eliminating tension produced by muscular forces surrounding the scar in the face and elsewhere. Gassner and colleagues first demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in the appearance of forehead lacerations immobilized by BoNT compared to control wounds in primates in 2000; a subsequent randomized, placebo-controlled study of 31 human subjects presenting with traumatic forehead lacerations or undergoing elective excisions of forehead masses showed that patients who received BoNT in the musculature adjacent to the wound within 24 hours experienced enhanced healing and cosmesis (Fig. 22.6). Choi and colleagues showed that postoperative treatment with BoNT prevented complications in a series of 11 patients at high risk of impaired wound healing after complex eyelid reconstruction, and Flynn found that intraoperative BoNT aided wound healing in patients undergoing surgical reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of skin cancer.

Table 22.4 Adjunctive BoNT to promote wound healing and improve the appearance of scars

| Indications for adjuvant therapy | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Anywhere; particularly useful in areas of greater mobility, such as the periorbital or perioral regions |

Alster TS. Laser resurfacing of rhytides. In: Alster TS, ed. Manual of cutaneous laser techniques. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997:104–122.

Balikian RV, Zimbler MS. Primary and adjunctive uses of botulinum toxin type A in the periorbital region. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 2007;40:291–303.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Botulinum toxin type A: history and current cosmetic use in the upper face. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2001;20:71–84.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Cohen J. A prospective, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, dose-ranging study of botulinum toxin type a in female subjects with horizontal forehead rhytides. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29:461–467.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Monheit GD, et al. Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group study of the safety and effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA and hyaluronic acid dermal fillers (24-mg/mL smooth, cohesive gel) alone and in combination for lower facial rejuvenation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(suppl 4):2121–2134.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Combining botulinum toxin injection and laser for facial rhytides. In: Coleman WP, Lawrence N. Skin resurfacing. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:235–243.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. The adjunctive usage of botulinum toxin. Dermatologic Surgery. 1998;24:1244–1247.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. A prospective, randomized, parallel group study analyzing the effect of BTX-A(Botox) and nonanimal sourced hyaluronic acid (NASHA, Restylane) in combination compared with NASHA (Restylane) alone in severe glabellar rhytides in adult female subjects: treatment of severe glabellar rhytides with a hyaluronic acid derivative compared with the derivative and BTX-A. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29:802–809.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. The effect of full-face broadband light treatments alone and in combination with bilateral crow’s feet botulinum toxin type A chemodenervation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2004;30:355–366.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A, Maberley D. Deep resting glabellar rhytides respond to BTX-A and Hylan B. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29:539–544.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A, Tezel A, et al. Volumizing with a 20-mg/mL smooth, highly cohesive viscous hyaluronic acid filler and its role in facial rejuvenation therapy. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:1–7.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A, Zelichowska A. The power of combined therapies: Botox and ablative facial laser resurfacing. American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery. 2000;17:129–131.

Choi JC, Lucarelli MJ, Shore JW. Use of botulinum toxin in patients with high risk of wound complications following eyelid reconstruction. Ophthalmologic and Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 1997;13:259.

Coleman KR, Carruthers J. Combination therapy with BOTOX and fillers: the new rejuvenation paradigm. Dermatologic Therapy. 2006;19:177–188.

Fagien S, Brandt FS. Primary and adjunctive use of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) in facial aesthetic surgery: beyond the glabella. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 2001;28:127–148.

Flynn TC. Use of intraoperative botulinum toxin in facial reconstruction. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35:182–188.

Frankel AS, Kamer FM. Chemical browlift. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 1998;124:321–323.

Gassner HG, Brissett AE, Otley CC, et al. Botulinum toxin to improve facial wound healing: A prospective, blinded, placebo-controlled study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2006;81:1023–1028.

Gassner HG, Sherris DA. Chemoimmobilization: improving predictability in the treatment of facial scars. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2003;112:1464–1466.

Gassner HG, Sherris DA, Friedman O. Botulinum toxin-induced immobilization of lower facial wounds. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 2009;11:140–142.

Gassner HG, Sherris DA, Otley CC. Treatment of facial wounds with botulinum toxin A improves cosmetic outcome in primates. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2000;105:1948–1953.

Goodman GJ. The use of botulinum toxin as primary or adjunctive treatment for post-acne and traumatic scarring. Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery. 2010;3:90–92.

Hedelund L, Due E, Bjerring P, et al. Skin rejuvenation using intense pulsed light: a randomized controlled split-face trial with blinded response evaluation. Archives of Dermatology. 2006;142:985–990.

Huilgol SC, Carruthers A, Carruthers JD. Raising eyebrows with botulinum toxin. Dermatologic Surgery. 1999;25:373–375.

Khoury JG, Saluja R, Goldman MP. The effect of botulinum toxin type A on full-face intense pulsed light treatment: a randomized, double-blind, split-face study. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34:1062–1069.

Patel MP, Talmor M, Nolan WB. Botox and collagen for glabellar furrows: advantages of combination therapy. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2004;52:442–447.

Sherris DA, Gassner HG. Botulinum toxin to minimize facial scarring. Facial Plastic Surgery. 2002;18:35–39.

Weiss RA, Weiss MA, Beasley KL. Rejuvenation of photoaged skin: 5 years results with intense pulsed light of the face, neck, and chest. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28:1115–1119.

Weiss RA, Weiss MA, Munavalli G, et al. Monopolar radiofrequency facial tightening: a retrospective analysis of efficacy and safety in over 600 treatments. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2006;5:707–712.

West TB, Alster TS. Effect of botulinum toxin type A on movement-associated rhytides following CO2 laser resurfacing. Dermatologic Surgery. 1999;25:259–261.

Wilson AM. Use of botulinum toxin type A to prevent widening of facial scars. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;117:1758–1766.

Worcester S. Use of Botox before and after laser facial resurfacing. Skin Allergy News. Online. Available: http://www.skinandallergynews.com, 2000.

Xia Z, Zhang F, Cui Z. Treatment of hypertrophic scars with intralesional botulinum toxin type A injections: a preliminary result. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2009;33:409–412.

Yuraitis M, Jacob CI. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of facial flushing. Dermatologic Surgery. 2004;30:102–104.

Zimbler MS, Holds JB, Kokoska MS, et al. Effect of botulinum toxin pretreatment on laser resurfacing results: a prospective, randomized, blinded trial. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 2001;3:165–169.

Zimbler MS, Nassif PS. Adjunctive applications of botulinum toxin in facial aesthetic surgery. Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2003;11:477–482.

Zimbler MS, Holds JB, Kokoska MS. Effect of botulinum toxin pretreatment on laser resurfacing results: a prospective, randomized, blinded trial. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 2001;165:165–169.