Chapter 26 Combat and Casualty Care

For online-only figures, please go to www.expertconsult.com

![]()

The Beginnings of Military/Operational Medicine

The first “operational wilderness medicine” courses and training were created centuries ago by military forces. Operational and wilderness medicine requirements have shared a long and symbiotic relationship with exchange of information, lessons learned, and equipment between the military and those physicians and responders willing and able to work in austere environments. Much of the knowledge, both remotely and recently, has benefited emergency care in general and wilderness medicine in particular. Much of the equipment and expertise now used by the military have resulted from improvements and refinement of wilderness medicine professionals. One of the first wilderness medicine experts to document wilderness medicine knowledge was Ibn Al Jazzar (circa AD 895-979) a physician from the Medical School of Kairouan in what is now Tunisia, once known as Carthage, the home of Hannibal (circa 200 BC). He wrote the then landmark wilderness medicine manuscript, Zad El Mousa Fir-Wa Qaout El Hadhir (Provisions for a Voyager Traveling Afar and for the Day’s Subsistence).56

Introduction

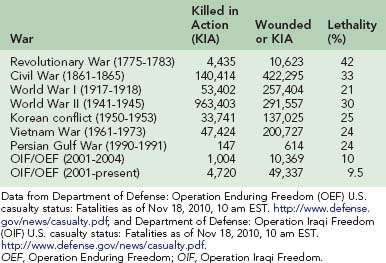

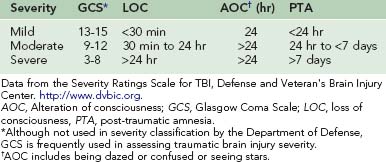

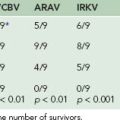

In ancient times any significant injury was likely to result in death. In the Revolutionary War, lethality of combat injury was 42%. In the Civil War, the combat mortality rate was 33% for persons wounded; this decrease was due to improvements made in evacuation from the field with an ambulance corps and surgical care closer to the field. Even with the horrors of chemical munitions and trench warfare, World War I showed a decrease in war injury deaths to 21%. Great strides were made in World War II, including antibiotics and blood/plasma replacement; however, the combat mortality rate remained high at 30%. Korea moved Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals to the front and was the first conflict to routinely use air transport to get injured soldiers to the surgeons. The Korean conflict mortality fell to 25%. Vietnam further emphasized quick evacuation to combat hospitals, but the mortality rate remained steady at 24%.56 In Vietnam, fewer than 3% died after arrival at a combat hospital, attributed to meaningful medical interventions being made earlier.28,29,34 Most deaths were due to hemorrhage and airway/breathing compromise. Desert Storm in 1991, with a short but very intense combat phase, recorded 159 deaths from 626 total traumatic injuries, for a mortality rate of 25%. Military medical leadership studied previous lessons and created a better medical field response. The rates of mortality in the current conflicts of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom are the lowest seen in the history of conflict. Combat lifesavers (first responders) and then combat medics are at the scene immediately and buy time for injured soldiers. The likelihood of coming home is over 90%24,28,29,34,40 (Table 26-1).

In addition, disease, nonbattle injury (DNBI) has been a constant concern for the field surgeon and medic. The outcome of many conflicts has been determined by DNBI. Athens fell to Sparta in 430 BC as a result of an unknown communicable disease. DNBI affecting the outcome of conflict played out again in the trench warfare of World War I, and DNBI was deadly even in the same region of Gallipoli where the British and Australians lost many soldiers to dysentery and other nonbattle injuries.33 In the U.S. Civil War, for every death due to trauma, there were three deaths due to DNBI and starvation. In the Russian-Afghan war over the course of 10 years, the war’s outcome was influenced greatly by disease; some contend that Russia was “beaten by the bugs.”37

Regardless of environment, combat units within a battle space require medical capability. This capability is also used for injured civilians and forces that have laid down their arms. As strong as military medicine is as a force multiplier, it is also often used as a national engagement tool to shorten conflict, because medicine’s center of gravity and power is science and humanity, not geography, religion, or politics. When used in this manner, medicine may enhance progress toward peace.60

Combat Medicine Compared With Standard Civilian Prehospital Care

In conflict environments, completion of the mission and preserving one’s own forces take precedence. Medicine has a place in the tactical environment but is relegated to a secondary role at certain points. Mission-focused combat care is divided into three distinct classifications designed to support the mission: decrease loss of life using principles of triage, take care of immediate life threats with simple interventions of proved benefit, and save as many lives as possible through rapid evacuation. These phases of care do not normally rely on a complete assessment, physical examination or evaluation of past medical history, as might be expected in a secure location in a routine field emergency situation.17,18

The first phase of care, also known as care under fire, can be thought of as any event in which one is called on to render aid in an uncovered, unsecure, or potentially life-threatening situation. One cannot and should not “treat in the street” in a hostile environment. The first action will be to return fire and take cover (or take cover and return fire if more appropriate). There are many reflexive and simultaneous actions that will take place in this phase if the soldiers have been trained and drilled to an adequate degree of fine muscle memory. If one is able to provide care in this phase, the clinical intervention is likely to be only the most basic, such as moving the patient to a covered area to avoid further injury or placing a tourniquet. The usual protocols for ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) may be reordered to CAB in order to focus on the interventions most likely to have the greatest impact on outcome in the working time frame.63

Care under fire may simply determine whether or not a person is still alive. Mortal wounds or conditions such as an unresponsive patient without a carotid pulse are circumstances in which cardiopulmonary resuscitation would not be performed. After this phase is over, it is important to not forget security issues. These are easily overlooked because of euphoria that may result from the relief of surviving, or the need to begin to care for one’s comrades.18,63

Scopes of Practice for Combat Lifesaver, Combat Medic

Injured soldiers are unlikely to see a physician at the point of wounding. The Army has taken the civilian trauma system lessons of the “golden hour” to the next stage in what it calls the “platinum 10 minutes,” using combat lifesavers and combat medics to provide initial response on the battlefield. Many military emergency physicians note that in that first few minutes, there should be no qualitative difference in the response to traumatic injury between the medic and the physician. Given the same aid bag, the same set of circumstances, and the same patient, the expectation is that the same immediate lifesaving interventions will be made.63

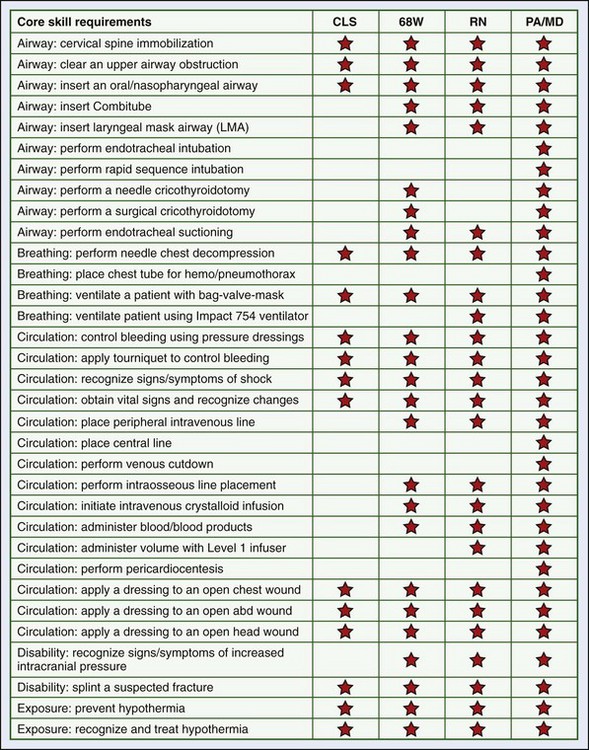

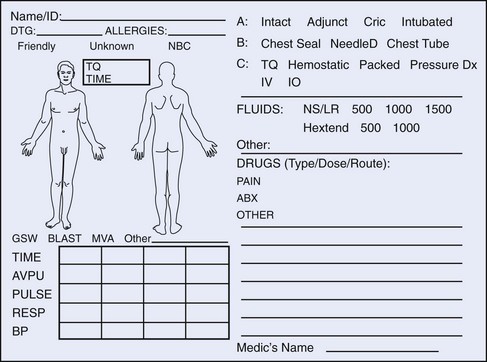

Combat lifesavers are first responders that are sometimes called the “battle buddy” of the medic. They buy time for the patient after the initial trauma. Their primary military occupational specialty may be that of infantry, aviation, maintenance, or other military nonmedical specialty, but after the situation is secured, they offer an extra set of hands for the medic. In addition to basic first aid, they are able to provide such skills as to deploy nasopharyngeal airways, apply tourniquets, or perform needle chest decompression for breathing difficulty after a penetrating wound to the chest (Figure 26-1).5 They do not, however, initiate intravenous (IV) lines or perform certain other advanced skills.

The combat medic is also known by the designation 68W (68 Whiskey). The scope of practice of the combat medic is most analogous to an EMT-Intermediate, with some special skills training in combat operational medicine based on the security, sick call, and unit issues with which the medic must deal. Additional airway skills include use of an adjunct such as a Combitube or King LT device and surgical cricothyrotomy (see Figure 26-1). The 68W is also taught the skills of needle chest decompression and chest tube placement. The 68W has the ability, with special training, to place an IV or intraosseous line and in certain cases administer blood products. The 68W has additional training in management of shock, including resuscitation from hypotension and prevention of hypothermia. Because closed head injury, burns, and stress reactions are prevalent wounds of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, combat medics are entrusted with the initial evaluations of these problems. If the patient cannot be evacuated in a timely fashion, the combat medic may initiate protracted care, to include the placement of a nasogastric tube and urinary catheter. Combat medics also have the capacity to perform limited primary care, using protocols for minor sick call problems, and assist with monitoring for DNBI. They are given training in international humanitarian law (Geneva Law) focused on the rights, duties, and responsibilities of combat medics in areas of armed conflict, as well as caring for detainees.

Levels of Care and Capabilities

Military Health System Echelons of Care

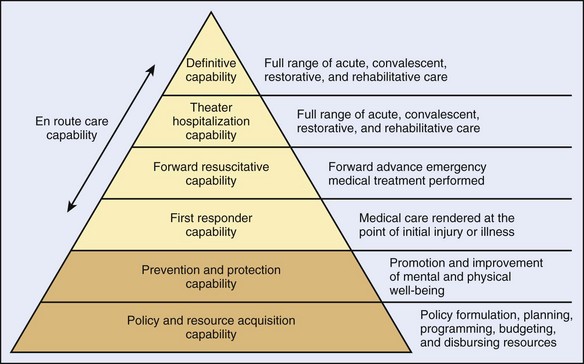

The continuum of care in the military extends from the point of wounding to a battalion aid station (BAS), usually staffed by a physician assistant and/or physician, to the forward surgical team (FST) to the CSH (Figure 26-2).26 At each point of care, the level of surgical and holding capability increases. Military medical planning includes support at each of these levels.3,27,31,54

FIGURE 26-2 Taxonomy continuum of health care capabilities.

(From Defense Medical Readiness Training Institute: Joint operations medical managers course guide, San Antonio, Tex, 2009.)

Level V

Theater Trauma System

Much of the improvement in survival rates in the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts is directly attributable to implementation of a trauma system. In both military and civilian populations, large numbers of patient requiring treatment for trauma or illness are best served through a “system approach.” The best systems have a designated trauma system director who is responsible for data acquisition, critical review of collected records, development of medical policy and practice guidelines, and ongoing evaluation of medical resources utilization, including staffing.37

Joint Theater Trauma Registry

The Joint Theater Trauma Registry (Figure 26-3) is a key component of the Joint Theater Trauma System and was implemented in November 2004. As would any civilian trauma system, it collects the usual demographic and mechanism of injury data points. In addition, it collects information on unique transportation solutions, protective gear, service affiliation of the injured, and some unique aspects of conflict injuries (e.g., chemical, nuclear). This information has been analyzed extensively to develop and improve clinical practice guidelines, protective measures, medical and nonmedical training and best practices for patient care from the prehospital resuscitation, to damage control surgery, through rehabilitative care. The data have a very high fidelity in the fixed facilities but are less complete directly from the field.20,15,16,30

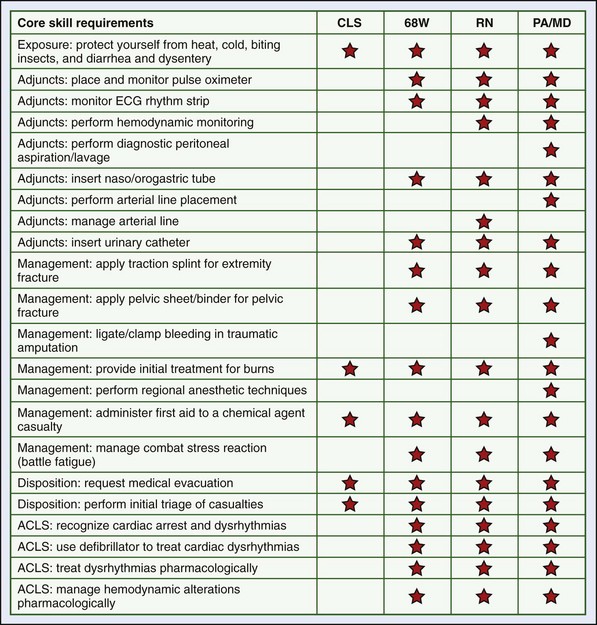

The military has experimented with the Battlefield Medical Information System–Tactical (BMIST), an electronic data collection system. It is still the goal to use an electronic patient care recorder. Though relatively lightweight, the BMIST weighs 11.1 to 14.1 oz; every item in a combat medic’s aid bag increases difficulty in mobility and decreases treatment items. Currently, as a fail-safe method, a simple tactical combat casualty care (TCCC; also referred to as TC3 in other venues) card (Form DA 7656) is used and carried in the soldier’s IFAK. If the soldier is injured, this card is completed as best possible and moves with the patient to the treatment facility, where it is able to be scanned into the record. It is a better method of recording trauma data than was the previous field medical card (Figure 26-4).

Unique Aspects of Military Triage and Other Considerations

An interesting illustration of the need for continued combat effectiveness was described in World War II, where penicillin was first used extensively for wound infections. Penicillin was very effective in the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), also seen in the military population. Because of its limited availability, penicillin was rationed and at times used first for those soldiers with sexually transmitted diseases rather than for the badly wounded, to keep the fighting forces at the front.53

Clinical Applications of Lessons Learned

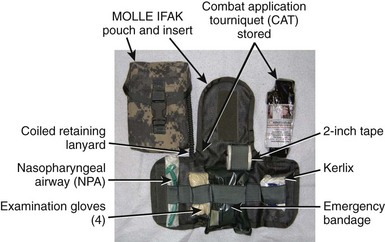

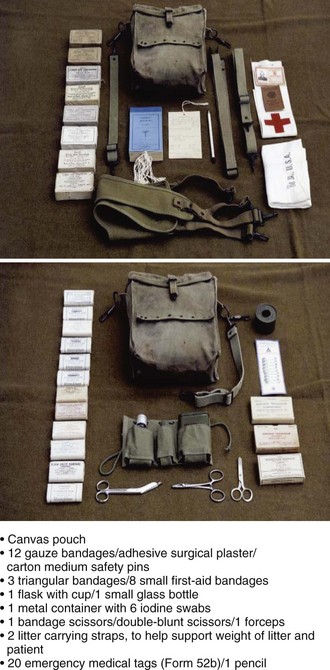

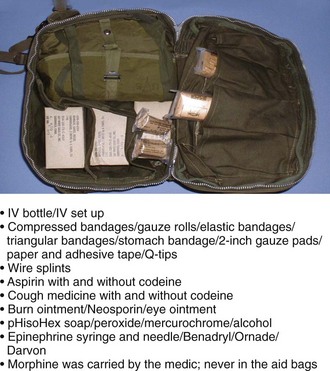

Soldier Medical First Aid Kits (Figures 26-5 to 26-7) and Warrior Aid and Litter Kit

Improved survival rates in the current conflicts have been evaluated to search for further improvements. The reasons given for the 90% survival, even with increased lethality of wounding agents, are improved personal protective equipment, adherence to TCCC precepts, faster evacuation, and better-trained medics. The IFAK (see Figure 26-5) was developed based on the continuous review of injuries and is carried by every deployed soldier. It contains the essential items to address the major causes of preventable combat death: compressible hemorrhage, airway compromise, and tension pneumothorax. The IFAK contains a combat application tourniquet (CAT), kaolin-impregnated rolled gauze (Combat Gauze) that promotes hemorrhage control, 15.2-cm (6-inch) compression dressing (Israeli Trauma Bandage), nasopharyngeal airway, and 8.9-cm (3.5-inch) 14-gauge IV catheter for needle chest decompression. Hemorrhage is the leading cause of combat death. Interestingly, combat injuries have remained relatively similar in distribution since the Civil War; extremity injuries are the most common.

FIGURE 26-5 Improved First Aid Kit (IFAK) components. MOLLE, Modular lightweight load-carrying equipment.

(From Army Medical Department Center and School: Briefing on Combat Equipment, 2007.)

FIGURE 26-6 World War II aid bag.

(From Army Medical Department Center and School: Briefing on Combat Equipment, 2007.)

FIGURE 26-7 M5 Vietnam aid bag. IV, Intravenous.

(From Army Medical Department Center and School: Briefing on Combat Equipment, 2007.)

A Warrior Aid and Litter Kit (Figure 26-8) is carried on vehicles, although it can also be easily dismounted and carried via shoulder straps to the point of wounding. The additional equipment increases a unit’s capabilities to provide self-aid/buddy-aid for multiple casualties and interventions for the three leading causes of death on the battlefield. Furthermore, it provides a military squad the ability to evacuate a nonambulatory casualty (folding litter) and increases survivability during dispersed operations (i.e., improvised explosive device [IED]/rocket-propelled grenade [RPG] attack on convoy).

Hemostatic Agents and Tourniquets

The U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research in San Antonio, Texas, finds that one-half of those injured in combat suffer “potentially survivable” wounds. Eighty percent of these are hemorrhage. In these bleeding events, 30% are in the extremities and “compressible,” where a tourniquet can be used to stop bleeding; 20% are in the neck, groin, axillae, or areas where a tourniquet cannot be used, but pressure can be applied to stop bleeding; and thorax or abdominal account for the remaining 50%, where surgical intervention is necessary.8,20,23

Jean Louis Petit, a French surgeon, developed a screw device in 1718. He coined the term tourniquet from tourner (to turn).64 The earliest known usage of a tourniquet dates back to 199 BC. Tourniquets were used by the Romans to control bleeding, especially during amputations. These tourniquets were narrow straps made of bronze covered with leather (Figure 26-9). These look remarkably similar to the CAT (Figure 26-10) used today.

FIGURE 26-9 Roman tourniquet.

(Courtesy Science Museum, London. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/objects/display.aspx?id=4304.)

The CAT was selected after extensive testing and research. Other methods, such as a triangular bandage and sticks, can be used if a CAT is unavailable. The imperative is to occlude the distal pulse. It may take multiple tourniquets to accomplish obliteration of the pulse. Do not remove previously applied tourniquets if bleeding continues; tighten the tourniquet further if possible, or apply another tourniquet proximal to the first.63

A bandage that stops bleeding has been sought for centuries. Combat Gauze, which is a kaolin-impregnated Kerlix gauze, is the best hemostatic dressing at this time. Other agents have been reviewed and/or used but had drawbacks. Factor concentrators, such as QuikClot, that removed water from blood, created a significant exothermic reaction, were difficult to use in some environments, and were difficult to wash out of wounds. WoundStat used concentrated clotting factors without a significant increase in temperature, but caused some tissue damage and embolic episodes. Mucoadhesive vehicles, such as HemCon, Chitoflex, TraumaStat, and Celox, were made of shrimp exoskeletons. Although tissue damage was not seen, the hemostatic properties were not as robust as those seen with Combat Gauze. Combat Gauze is a procoagulant supplement that uses gauze impregnated with Kaolin (active agent is aluminum silicate) and is the hemostatic dressing issued to the U.S. military for combat use. In the future, fibrin dressings and spray-on sealants may become available.1,13,22,44–46

Tourniquets cause ischemia in the treated extremity. Release of a well-placed and functioning tourniquet after several hours releases lactic acid and potassium generated by anaerobic metabolism and cell injury. Before removal of a tourniquet that has been in place for any significant period of time, make sure the patient is well hydrated and as fully resuscitated as is reasonably possible, and consider adding 50 mEq of sodium bicarbonate to a liter of IV fluid for administration. Release the tourniquet slowly. If cardiac arrhythmias occur, reapply the tourniquet and wait to remove it until after further fluid resuscitation and sodium bicarbonate is administered. If the limb is “dead,” the overriding tenet is “life over limb.” Consider a fasciotomy (four compartment) in any lower extremity with extensive tourniquet time (over 2 hours).10

The Airway in Combat

In emergency medicine, clinicians are always taught to control cervical spine (c-spine) movement by using a hard collar and immobilizing the patient on a spine board. However, this approach may cause further airway complications in a patient with significant penetrating facial trauma. Blunt forces cause c-spine injury in 2% to 6% of patients in civilian studies and may be up to 10% in patients with extensive blunt facial trauma. Unstable cervical spine trauma is uncommon in neurologically intact patients with penetrating (as opposed to blunt) force injuries.12,48,51

In many cases, simple positioning or use of a nasopharyngeal airway will allow an adequate airway until definitive treatment is available. If the patient is able and wants to sit up, it is preferable to allow this rather than suffer an airway loss. The contraindications for combat nasopharyngeal airway placement are severe head or facial injuries, evidence of a basilar skull fracture (e.g., Battle’s sign, raccoon eyes, cerebrospinal fluid/blood from ears), or known coagulopathy. Loss of a marginal airway can occur quickly if medications with sedating properties are used, so it is best to defer these until medical personnel are ready to manage the airway. If pain medications are used, be prepared to take over the airway.10

Hypothermia

Hemorrhage and trauma can be precipitating events for hypothermia. The combination of hypothermia (defined as core body temperature under 35° C [95° F]), acidosis, and coagulopathy put trauma patients at greater risk for multisystem organ failure and death. This triad was first described in 1982 as the “bloody vicious cycle.” Hypothermia itself inhibits coagulation. Under 32.2° C (90° F), hypothermia is life threatening by affecting cardiac and respiratory function. Hypothermia is seen commonly in trauma patients, even in environments where heat injury might seem more likely. The Joint Theater Trauma System noted that patients evacuated to the combat support hospitals were hypothermic, and the system developed a hypothermia clinical practice guideline, which is emphasized by the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care and its training recommendations.3,7,39

Prevention measures are protection from the environment, removal of wet clothing (blood or other fluids), keeping the patient covered, and using adjuncts such as the Hypothermia Prevention Management Kit (HPMK). The latter is especially useful during the CASEVAC phase, where prevention of hypothermia may be difficult due to altitude, flying with open doors, and the injury. The HPMK has a self-heating, four-cell shell liner that is able to sustain continuous dry heat, and a skull cap to keep the patient warm.63 Also, if portable fluid-warming devices, such as the Thermal Angel Blood Warmer, are available, they should be used on all IV fluid sites. If adjuncts are unavailable, one uses whatever is at hand, such as dry blankets and sleeping bags. Wool blankets alone are not particularly good at keeping the patient warm, but a “hot pocket” has shown good results to prevent passive heat loss. This method puts the patient in a body bag, covered in two wool blankets and a space blanket, with an opening for an endotracheal tube.2,10

Damage Control Surgery

Damage control is a planned management of the patient with three defined phases:

This care continues as the patient is moved through the evacuation process to definitive care.3,10,57

Blood

The U.S. Army clinical practice guideline for damage control resuscitation (with massive transfusion defined as >10 units of red blood cells [RBCs] in under 24 hours) was instituted in March 2006. It endorsed a 1 : 1 fresh frozen plasma (FFP) to RBC transfusion ratio with less emphasis on crystalloid use.49,59,62

Factor VIIa

Factor VIIa was first reported used for trauma in 1999 for an Israeli soldier in extremis due to a high-velocity gunshot wound with disruption of the inferior vena cava.43 In the U.S. military, factor VIIa is used in uncontrollable hemorrhage with significant coagulopathy as an addition to FFP and packed red blood cells in a 1 : 1 ratio. Platelets are given if massive transfusion is necessary. Factor VIIA requires adequate platelets for optimal results. Acidosis must be corrected in order for it to work. There is a theoretic risk for deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and myocardial infarction. However, prospective randomized trials and retrospective trials on combat wounded have not shown any increase in thromboembolic events.

Wounds

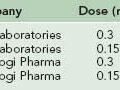

Combat wounds range from minor to devastating. All require meticulous care and can initially be deceiving as to extent. For the initial combat wound, the soldier takes antibiotics that are supplied in the combat pill packs. The usual antibiotic is moxifloxacin 400 mg orally (PO) once a day. If the soldier is unable to take oral medications, then cefotetan 2 g IV or intramuscularly (IM) every 12 hours (or ertapenem 1 g IV or IM) once a day is administered. Even though most soldiers have current immunizations, one must consider tetanus immunization status in all wounds. This is especially true in nonmilitary personnel. Antibiotic prophylaxis is included for any penetrating wounds to the eyes/globe.*

Wounds from blast injury include burns, tissue loss, and/or extensive maceration. These injuries should all be treated as though there is underlying structural injury until proved otherwise; these patients are often candidates for damage control resuscitation and surgery. Initially bleeding may be unimpressive, but it can increase with improvement in blood pressure, warming, and manipulation during exploration, debridement, and irrigation. Primary closure of wounds is rarely considered.10,50 After debridement, the wound should be packed with rolled gauze. If necessary, the skin is sutured over the packing for tamponade of bleeding. This is a temporary measure for life-threatening bleeding until damage control resuscitation is under control.3,10

Injuries to large arteries and veins need to be controlled and may require a tourniquet, pressure dressing, vascular shunt, or ligation. In initial damage control surgery, a nasogastric tube or IV tubing can be used as a temporary vascular shunt, and the aorta can be shunted with a small pediatric chest tube. If a shunt is performed and the patient is to be transferred, a tourniquet should be placed loosely (i.e., not tightened) proximal to the shunt for transport in case of shunt dislodgment. Similarly a nontightened tourniquet should be placed before evacuation after amputation to be prepared for bleeding.10

Wound Vacuum-Assisted Closure (VAC)

Wound care has been a defining characteristic of military medical care through the ages. The principles are cleansing, debridement, and elimination of effects harmful to the wound (such as wound cautery used in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance). In today’s battlefield, more soldiers survive blasts, high-velocity missile strikes, and other combat injuries because of better protective gear, highly trained combat medics, and faster evacuation to surgical care. These survivors have complex wounds with high probability of infection that are unable to be closed primarily. They require not only adherence to the basics, but new modalities and a team approach to care that involves physical and emotional care.3,10,50,54

Vacuum wound closure systems and their benefits as an important adjunct to modern combat wound care are discussed in the U.S. Department of Defense’s Emergency War Surgery,3 First to Cut: Trauma Lessons Learned in the Combat Zone,10 and War Surgery in Iraq and Afghanistan: A Series of Case Studies, 2003-2007.54 These also describe field-expedient methods to produce a wound VAC system with available equipment.

Burns

Prehospital burn care is the same as that for civilians with a few additional considerations. The burn patient in a combat zone must be considered for additional injuries, wounds, hemorrhage, and possibly blast injury. If this is the situation, Hextend is used as per the shock protocols along with crystalloid (lactated Ringer’s) burn resuscitation. The amount of Hextend used should not exceed 1000 mL. The U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research Burn Center, which serves as the U.S. Department of Defense burn center, developed a new fluid resuscitation “rule of 10” used for burns greater than 20%. It is based on current research regarding burn resuscitation.10,21

Pain Management

There Patroclus made him [Eurypylus] lie at length, and with a knife cut from his thigh the sharp-piercing arrow, and from the wound washed the black blood with warm water, and upon it cast a bitter root, when he had rubbed it between his hands, a root that slayeth pain, which stayed all his pangs; and the wound waxed dry, and the blood ceased. (Figure 26-11, online)

FIGURE 26-11 Achilles taking care of Patroclus.

(Courtesy Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achilles_and_Patroclus.)

Pain is a common manifesting symptom in injuries directly related to combat. In the deployed environment, there are also other more ordinary causes of pain, such as motor vehicle accidents, long periods in confined spaces, heavy personal protective equipment, and lifting and training accidents.9,38

The military is performing ongoing research into pain relief on the battlefield. The challenges are distance, security situations that may delay transport, provider inexperience, and severity of the injuries.9,38 Causalgia (reflex sympathetic dystrophy) was a common diagnosis seen after the Civil War, and chronic pain states are still seen today in patients without adequate pain management. Current studies indicate that the cause or exacerbation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is related to poorly or untreated, unrelenting pain.38

At the point of wounding for severe pain, the combat medic (68W) is able to give morphine 5 mg in titrated doses IV (preferred), IO, or via IM injection. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate 400 to 800 mcg6,32 is an alternative to morphine for use before arrival at a combat support hospital. Naloxone is available for respiratory depression. Promethazine 25 mg (IV/IM/IO) every 6 hours as needed has been added to the prehospital pain medication regimen to treat the nausea that is common with injury and often seen with narcotic administration. If the patient is treated with these medications, his or her weapon is secured and the patient is no longer able to fight. Splinting, positioning, and emotional support are provided as the patient is prepared for evacuation.

Military members in combat carry a combat pill pack, which is taken as soon as possible after injury or wounding. These are oral medications: meloxicam 15 mg (a cyclooxygenase-2-inhibitor selective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug) once a day and acetaminophen 650 mg (bilayer caplet) two pills every 8 hours. These medications were chosen for the ability to relieve moderate pain without causing platelet dysfunction or decrease in mental alertness. The soldier is still able to carry a weapon and able to fight if necessary. An antibiotic is carried in the combat pill pack and used for all open combat wounds. Currently the antibiotic of choice is moxifloxacin 400 mg PO once a day.63

After arrival at a BAS, FST, or CSH, other medications and modalities are available. Low-dose ketamine is an excellent analgesic. In the future, intranasal ketamine may be an option10 Clonidine may be used in stable patients.9,38 Peripheral nerve blocks and regional blocks (if trained personnel are available) offer excellent relief. A fascia iliaca block is useful for pain relief of injuries involving the hip, anterior thigh, and knee. This block is useful for fractures of the hip and proximal femur, especially before prolonged transport. Intercostal blocks are beneficial for chest wall pain after trauma, especially in the presence of rib fractures.

Telemedicine

Telemedicine has been used successfully to diagnose dermatologic conditions, send radiologic studies for interpretation, and give reports on patients being evacuated to higher levels of care. Combat medics in remote sites have used e-mail contact with their unit physician assistant or physician to make determinations of evacuation or therapy for ill or injured soldiers. The U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command and the Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center have worked on surgical robots and mentoring programs to assist in surgery. Colonel Bruce Adams has successfully experimented with camera observation and advice to combat medics for assistance in performance of surgical cricothyrotomy on manikins. Although telemedicine currently has limitations because of bandwidth, privacy issues, and urgency of trauma patient consultations, it holds promise for the future.47

Casualty Evacuation (CASEVAC)

At the point of wounding, the evacuation platform is more often going to be a tactical vehicle than any sort of ambulance. Due to increased use of IEDs and RPGs, most vehicles are armored or hardened. The space is very limited, so to the greatest extent possible, any control of bleeding, placement of tourniquets, and other medical procedures are accomplished before transport. It is also important to work with equipment such as litters to make sure they will fit in the vehicles. During transport, it is critical to ensure medical interventions, such as control of bleeding, remain intact. For the badly injured casualty, evacuation from the time and point of wounding to the closest and most appropriate initial care at an FST or CSH averages about 1 hour. If the determination is that there is a lesser injury, the patient can be taken to a BAS for a determination of injury and evacuated to a higher level later if required.54

Transportation after initial advanced-level care often involves an intubated (and possibly ventilated) patient. Sedation and analgesia are essential for these transfers. In addition, no paralytic agent should ever be given without a potent sedative. Some evidence suggests that the administration of sedation and pain relief may decrease the probability of later PTSD. Absent hypovolemia, a sign of inadequate pain and sedation may be persistent tachycardia. The airway and patient should be adequately prepared because loss of the airway during combat evacuation is a major life threat. Reestablishment in a limited space with inability to hear breath sounds may necessitate a surgical airway. The attendant in transfer must have sufficient medications and doses to keep the patient comfortable and sedated and be able to provide an airway if the patient is extubated. For the most critical airways, the endotracheal tube may be wired onto the teeth.10

Death

In the midst of the savagery of war, it is critical to maintain the tether to humanity. Care of the deceased is an important service, not only for the soldier’s family, but for the unit’s morale and well-being. Although the care of remains is under the direction of the Quartermaster Corps, it is usual that no matter where the death occurs, the unit will bring the body to the medical personnel in the area. The body is cooled if at all possible. As in any medical examiner’s case in the United States, all medical procedure items are placed in the body bag with the deceased. Clothing and operational gear are transported with the remains. Any records of the incident are preserved and sent with the remains. A full autopsy is completed by the military to determine the cause of death and enter the data into the trauma registry. In response to the loss, the unit holds a memorial service, where the deceased soldier is represented by the Fallen Soldier Battle Cross. The cross consists of the soldier’s rifle with bayonet attached and stuck into the ground; the helmet is placed on top, accompanied by dog tags that hang from the rifle with the boots of the fallen soldier in front of it (Figure 26-12). Its purpose is to show honor and respect for the fallen at the battle site. The ceremony for the lost comrade is formal and used as a ritualized means to collectively acknowledge the commitment and sacrifice of the soldier and to mourn his or her loss. Commanders are cognizant of the distress brought by the death of a unit member, especially if the unit has suffered multiple losses. Commanders use this ceremony to reaffirm with unit members the sense of unity, cohesion, and commitment to each other as they pursue their shared sense of mission.

Veterinary Issues

Dogs in conflict areas are ubiquitous. Despite education and warnings, soldiers often voluntarily interact with local dogs. U.S. military working dogs are vaccinated against rabies; the likelihood of rabies in local animals may be considerable. Dog bite treatment is similar to that in any emergency department, except that the ability to catch and monitor the animal is decreased, so watchful waiting to determine vaccination status of an animal is not an acceptable approach. Therefore postexposure rabies immunization is started.10

Working dogs may be seen as patients in emergency treatment areas of the hospital, especially if a veterinarian is not immediately available. Care of working dogs is described in First to Cut: Trauma Lessons Learned in the Combat Zone.10 Basic damage control principles are used for resuscitation and surgery.

Unexploded Ordnance*

Currently, unexploded land mines represent a significant health problem in Southeast Asia, the Balkans, Central America, Egypt, Iran, and Afghanistan. The International Red Cross estimates that someone is killed or injured by a land mine every 22 minutes. The average number of mines deployed per square mile in Bosnia is 152; in Iran, 142; in Croatia, 92; and in Egypt, 59. There are a total of 23 million mines in Egypt alone.10

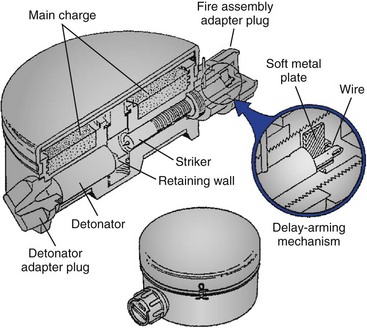

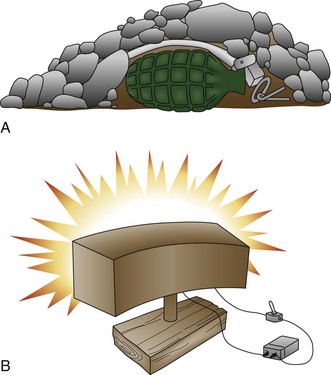

Land mines may be commercially manufactured or produced locally from available materials (Figure 26-13). Commercial land mines currently produced in the United States have a limited active life and self-destruct after their active life has expired. Unfortunately, this is not true of older types of mines or mines produced by other countries. Locally produced mines have no standard size, shape, or detonation pattern and may be very difficult to detect and defuse. These types of land mines are used extensively in El Salvador, Malaysia, and Guatemala.

Land mines have two primary functions, the first of which is to cause casualties—the so-called antipersonnel mines. These may be blast or fragmentation type. Fragments may be accelerated at 4,500 ft/sec (3068 mph), or double the speed of a high-velocity rifle. The fragmentation type may be either directional or nondirectional (Figure 26-14). Antipersonnel mines may cause lethal or nonlethal injuries in several persons. Wounded soldiers require more care than do killed soldiers, and the tactical effect may be the same. The second primary function is to destroy vehicles, such as tanks, so mines intended for this purpose are usually much larger.

Injuries from explosives can include any combination of blunt, penetrating, burn, or blast wave/pressure injury. Injury patterns are usually worse with closer proximity. These injuries can also involve cavitation, crush, embolism, fractures, lacerations, and perforations of organs. The primary blast injury is due to the pressure wave and the direct effects of the pressure pulses, both overpressure and negative pressures. Significant blast winds can be produced because of the detonation. Injury is most often associated with the gas-filled organs, middle ear, lungs, and intestines. Lung injuries cause the greatest morbidity and mortality. Rapid acceleration of shrapnel to 50 ft/sec (34.1 mph) lacerates tissue, and at 400 ft/sec (272.7 mph) shrapnel is able to penetrate body cavities. Because the wounds are deceptive, the need for amputation may first be recognized later. Tetanus prophylaxis must be rendered. The tertiary injuries involve the victim being accelerated by the blast and thereby impacting other objects when thrown any distance. The median lethal dose (LD50) of being thrown is about 26 ft/sec (17.7 mph), and the limit of human tolerance is about 10 ft/sec (6.8 mph). The other injuries that commonly may occur are burns, crush (from building collapse), and chemical exposures. A very important aspect of the care for any patient with an explosive munition mechanism of injury is the possible lack of any initial overt manifestation of injury. There must be a high index of suspicion because many victims will not manifest for several hours. The first sign of respiratory failure is usually increased respiratory rate. Acute respiratory distress syndrome may not manifest for 24 hours. Treatment of these injuries can be very complex and involves vascular, orthopedic, soft tissue, abdominal, and craniofacial procedures. In most of these injuries, massive debridement is necessary. Rarely, UXO may be embedded in soft tissues and body cavities and must be removed in the operating room, possibly endangering the lives of medical personnel. Initial treatment involves airway control, treating tension pneumothorax, and controlling hemorrhage. Tourniquets are often necessary to control the bleeding from amputated limbs. Splinting the injured extremity and covering the wound to prevent further contamination is necessary. Initial debridement must be done carefully; removal of fragments may cause bleeding to recur. Penetrating injuries of the pelvis and abdomen usually require laparotomy, and soft tissue injuries may require multiple reconstructive procedures. The wounds are usually highly contaminated with soil, clothing, and fragments that may be driven deeply into tissue proximal to the obvious injuries.39 Broad-spectrum antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis are appropriate in all cases, and fluid resuscitation is usually indicated with extremity injuries. Postsurgical infection of mine injuries is common and greatly increases morbidity and mortality. Most victims who survive never completely regain normal function, especially if the initial treatment was delayed or inadequate.

Generally speaking, the closer the victim is to the blast, the greater the injury. The tympanic membrane will rupture at overpressures of 5 to 7 psi. This causes acute hearing loss, pain, and tinnitus. Blast lung is caused by the overpressure wave passing through the chest wall and may involve one or both lungs. Chest pain, dyspnea, and hemoptysis may manifest immediately or be delayed up to 48 hours. Chest radiograph may show patchy or diffuse infiltrates, pneumothorax, subcutaneous air, and hemothorax. Implosion of air into the vascular system may cause air embolism and sudden death. Abdominal injuries in air blast are uncommon, but in water blast may manifest as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and tenesmus. Sigmoid and transverse colon injuries are most often seen, followed by small bowel and solid organ (such as liver and spleen) injuries from the water hammer effect. Abdominal injuries may have a delayed (up to several days) presentation. The key to therapy is to be suspicious of occult injuries in any victim of a blast, whatever the cause. Most injuries will manifest within the first hour; however, because injuries may be delayed in presentation, observation and close follow-up are critical. Treatment is generally supportive for ear and lung injuries and operative for abdominal injuries.*

Traumatic Emotional Stress in Austere Environments: The Continuum of Effects

“Current studies support that no single pattern of psychological consequences to disasters exists. However, human generated disasters appear to result in more severe, intrusive, and long term psychological consequences than natural disasters.”14

How Are Military Stress Reactions Characterized?

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

The symptoms of ASD and PTSD are very similar (Table 26-2). The proper diagnosis revolves around two issues that can be framed as questions: How long have the problems lasted, and are the problems getting better, worse, or remaining the same?

| ASD | PTSD |

|---|---|

| The diagnosis of ASD can be given only within the first month following a traumatic event. | If post-traumatic symptoms persist beyond a month, the clinician should assess for the presence of PTSD. |

| It includes a greater emphasis on dissociative symptoms. An ASD diagnosis requires that a person experience three symptoms of dissociation (e.g., numbing, reduced awareness, depersonalization, derealization, or amnesia). | The PTSD diagnosis does not include a dissociative symptom cluster. |

ASD, Acute stress disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Which Treatments Work?

In general, treatment focuses on helping people process their experiences in ways that decrease or eliminate their combat arousal state. Treatment strategies that have demonstrated usefulness include prolonged exposure therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, pharmacologic treatment, couple/family counseling, and spiritual support. In addition, adjunct pharmacologic management for problems of mood or anxiety may also be indicated. There may be a role for medication in the prevention of PTSD. Recent research by Holbrook and colleagues suggests that administration of morphine during early resuscitation and trauma care at or near the point of injury is associated with a lower risk for PTSD following injury.38

One of the greatest historical barriers to care has been the stigma associated with the need for behavioral health support. U.S. Army Vice Chief of Staff, General Peter Chiarelli, is an outspoken advocate for the identification and treatment of PTSD and the often-related issue of TBI (http://www.neuroskills.com/mtbi.shtml). He has been especially vocal in speaking about the terrible toll of stigma:

Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

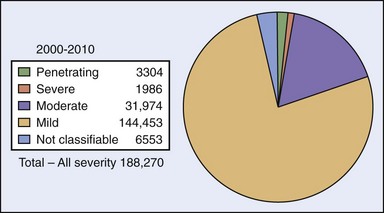

Mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) is commonly known as concussion; it is rarely life threatening (Figure 26-15). Gioia and Collins stated the following:

FIGURE 26-15 2000-2010: Traumatic brain injury categories.

(From Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center: Military Acute Concussion Evaluation. http://www.pdhealth.mil/downloads/MACE.pdf.)

Concussion (MTBI) is a complex pathophysiologic process affecting the brain, induced by traumatic biomechanical forces secondary to direct or indirect forces to the head. Disturbance of brain function is related to neurometabolic dysfunction, rather than structural injury, and is typically associated with normal structural neuroimaging findings (i.e., CT scan, MRI). Concussion may or may not involve a loss of consciousness (LOC). Concussion results in a constellation of physical, cognitive, emotional, and sleep-related symptoms. Symptoms may last from several minutes to days, weeks, months or even longer in some cases.36

Further, the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine52 characterizes MTBI as “a traumatically induced physiologic disruption of brain function which involves at least one of the following: 1) any period of loss of consciousness; 2) any loss of memory for events immediately before or after the accident; 3) any alteration in mental state at the time of accident (e.g. feeling dazed, disoriented, or confused); 4) focal neurologic deficit(s) that may or may not be transient.”

Signs and Symptoms

In patients presenting with possible head injury, initial medical response focuses on identification and management of the most serious injuries, so the diagnosis of MTBI may be delayed. The signs and symptom of MTBI are highly variable in both type and time. Headaches, for example, often have rapid onset, whereas many of the cognitive and affective behavioral symptoms may begin subtly and not become problematic for days or weeks. Disturbances in executive function, including decision making, foresight, insight, judgment, and planning, are frequently present. Most people with MTBI recover completely, but the process can sometimes take considerable time. This is especially the case for sufferers who are older, have a history of previous head injury, or who are taking psychiatric medications. Although patients recover, different symptoms may resolve at different rates, making the course of recovery highly variable.19

One of the most common pain symptoms of MTBI is headache that typically begins within the first 14 days. The patient may complain of a dull, aching pain that is typical of tension headache, but MTBI can also trigger migraine headaches in persons with a genetic disposition. Headaches often originate from structures external to the brain and skull, such as muscles and connective tissue of the skull, spine, and shoulder.52,58

Identification and Management of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in an Austere Environment (Table 26-3)

Assess

Austere environments do not typically lend themselves to thorough assessment of TBI; this is especially true in complex emergencies or other situations where security limitations preclude administration of a more comprehensive evaluation.42 In response, the military and Department of Veterans Affairs have developed tools to screen, assess, and longitudinally track and treat MTBI as a subset of TBI. For first responders, the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation (MACE) screening tool has demonstrated its usefulness. The MACE tool includes the Standard Assessment of Concussion, a four-part cognitive screening in the domains of orientation, immediate recall, concentration, and memory recall.42 It may be downloaded from http://www.pdhealth.mil/downloads/MACE.pdf.

1 Achneck HE, Sileshi B, Jamiolkowski RM, et al. A comprehensive review of topical agents: Efficacy and recommendations for use. Ann Surg. 2010;251:217.

2 Allen PB, Salyer SW, Dubick MA, et al. Preventing hypothermia: Comparison of current devices used by the U.S. Army with an warmed fluid model. U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research. 2010.

3 Army Medical Department Center and School. Emergency war surgery: Third United States revision. Washington, D.C.: Borden Institute: Walter Reed Army Medical Center; 2004.

4 Army Medical Department Center and School: Briefing on Combat Equipment, 2007.

5 Army Medical Department Center and School: Briefing on Combat Medic (68W) Skills, 2009.

6 Arnoff GM, Brennan MJ, Pritchard DD, et al. Evidence based oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OFTC) dosing guidelines. Am Acad Pain Med. 2005;6:305.

7 Beilman GJ, Blondet JJ, Nelson TR, et al. Early hypothermia in severely injured trauma patients is a significant risk factor for multiple organ dysfunction syndrome but not mortality. Ann Surg. 2009;249:845.

8 Belmont PJ, Goodman GP, Zacchilli M, et al. Incidence and epidemiology of combat injuries sustained during “The Surge” portion of Operation Iraqi Freedom by a U.S. Army brigade combat team. J Trauma. 2010;68:204.

9 Black IH, McManus J. Pain management in current combat operations. Prehosp Emerg Care. 223, 2009.

10 Blackbourne LH, Cancio L, Holcomb JB, et al. First to cut: Trauma lessons learned in the combat zone. Houston, Tex: United States Army Institute of Surgical Research; 2009.

11 Bond C, Hastings P, Ditzler T, et al. International humanitarian law and remains care lecture: Brigade combat trauma team training. Fort Sam Houston, Tex: Army Medical Department Center and School; 2010.

12 Brown JB, Bankey PE, Sangosanya AT, et al. Prehosptial spinal immobilization does not appear to be beneficial and may complicate care following gunshot injury to the torso. J Trauma. 2009;67:774.

13 Brown MA, Daya MR, Worley JA. Experience with chitosan dressings in a civilian EMS system. J Emerg Med. 2007;37:1.

14 Burkle FM. Complex Emergencies. For the International Committee of the Red Cross Health Emergencies in Large Population Course. Hawaii, 2000.

15 Burkle FM, Newland C, Orebaugh S. Emergency medicine in the Persian Gulf War: II. Triage methodology and lessons learned and combat casualty care. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:748.

16 Burkle FM, Orebaugh S, Barandse BR. Emergency medicine in the Persian Gulf War: I. Preparations for triage and combat casualty care. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:742.

17 Butler FK. Tactical combat casualty care: Update 2009. J Trauma. 2010;69:S10.

18 Butler FK, Hayman J, Butler E. Tactical combat casualty care in special operations: A supplement to military medicine. Mil Med. 1996;16:3.

19 CEU course. Mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI): Identification, assessment and treatment. http://www.neuroskills.com/mtbi.shtml.

20 Champion HR, Holcomb JB, Lawnick MM, et al. Improved characterization of combat injury. J Trauma. 2010;68:1139.

21 Chung KK, Wolf SE, Cancio LC, et al. Resuscitation of severely burned military casualties: Fluid begets more fluid. J Trauma. 2009;67:231.

22 Clay JG, Grayson JK, Zieold D. Comparative testing of new hemostatic agents in a swine model of extremity arterial and venous hemorrhage. Mil Med. 2010;175:280.

23 Combat casualty care conference shows promising research returns. August 18 http://www.fredericknewspost.com/sections/news/display.htm?storyid=108698, 2010.

24 Congressional Research Service: American war and military operations casualties: Lists and statistics. February 2010.

25 Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. Military Acute Concussion Evaluation (MACE). http://www.pdhealth.mil/downloads/MACE.pdf.

26 Defense Medical Readiness Training Institute: Joint operations medical managers course guide, San Antonio, Tex, 2009.

27 Department of Defense: Joint publication 4-02: Doctrine for health service support in joint operations, July 30, 2001.

28 Department of Defense. Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) U.S. casualty status: Fatalities as of Nov 18. http://www.defense.gov/news/casualty.pdf, 2010, 10 AM EST.

29 Department of Defense. Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) U.S. casualty status: Fatalities as of Nov 18. http://www.defense.gov/news/casualty.pdf, 2010, 10 AM EST.

30 Eastridge BJ, Jenkins D, Flaherty S, et al. Trauma system development in a theater of war: Experiences from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2006;611:366.

31 . Echelons of care. In Field manual 4-09, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/army/fm/4-0/chap9.htm, 2003.

32 Fleischman RJ, Frazer DG, Saya M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of fentanyl compared with morphine for out-of-hospital analgesia. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14:167.

33 The Gallipoli Campaign, Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallipoli_Campaign.

34 Gawande A. Casualties of war: Military care for the wounded from Iraq and Afghanistan. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2471.

35 Gerhardt RT, Matthews JM, Sullivan SG, et al. The effect of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis and wound irrigation on penetrating combat wounds in a return to duty population. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2009;13:500.

36 Gioia G, Collins M. Acute concussion evaluation (ACE) physician/clinician office version. http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/headsup/pdf/ACE-a.pdf, 2006.

37 Grau LW, Jorgensen WA. Beaten by the bugs: The Soviet-Afghan war experience. Military Review. 1997;77:30.

38 Holbrook TL, Galarneau MR, Dye JL, et al. Morphine use after combat injury in Iraq and post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:110.

39 Holcomb JB. Hypothermia commentary. In: Nessen SC, Lounsbury DE, Hetz SP, editors. War surgery in Iraq and Afghanistan: A series of case studies, 2003-2007. Washington, D.C.: Borden Institute: Walter Reed Army Medical Center; 2008:49-50.

40 Holcomb JB, Stansbury LG, Champion HR, et al. Understanding combat casualty care statistics. J Trauma. 2006;60:397.

41 Hospenthal DR, Crouch HK, English JF, et al. Response to infection control challenges in the deployed setting: Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2010;69:S94.

42 Jaffee MS, Helmick KM, Girard PD, et al. Acute clinical care and care coordination for the traumatic brain injury within Department of Defense. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:655.

43 Kenet G, Walden R, Eldad A, et al. Treatment of traumatic bleeding with recombinant factor VIIa. Lancet. 1999;354:1879.

44 Kheirabadi BS, Mace JE, Terrazas IB, et al. Safety evaluation of new hemostatic agents, smectite granules, and kaolin-coated gauze in a vascular injury wound model in swine. J Trauma. 2010;68:269.

45 Kheirabadi BS, Scherer MR, Estep JS, et al. Determination of efficacy of new hemostatic dressings in a model of extremity arterial hemorrhage in swine. J Trauma. 2009;67:450.

46 Lawton G, Granville-Chapman J, Parker PJ. Novel haemostatic dressings. J R Army Med Corps. 2009;155:309.

47 Ling GSF, Rhee P, Ecklund JM. Surgical innovations arising from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:457.

48 Lustenberger T, Talving P, Lam L, et al. Unstable cervical spine fracture after penetrating neck injury: A rare entity in an analysis of 1,069 patients. J Trauma. 2010, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20805776.

49 Makley AT, Goodman MD, Friend LA, et al. Resuscitation with fresh whole blood ameliorates the inflammatory response after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2010;68:305.

50 Manring MM, Hawk A, Calhoun JH, et al. Treatment of war wounds: A historical review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2168. Published online February 14 doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0738-5

51 Marion DW, Domeier R, Dunham CM, et al. Practice management guidelines for identifying cervical spine injuries following trauma. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma http://www.east.org/tpg/chap3.pdf, 1998.

52 Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee of the Head Injury Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine. Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1993;8:86, http://www.acrm.org/pdf/TBIDef_English_Oct2010.pdf.

53 Mitchell GW. A brief history of triage. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2:S4, http://www.dmphp.org/cgi/content/full/2/Supplement_1/S4.

54 Nessen SC, Lounsbury DE, Hetz SP. War surgery in Iraq and Afghanistan: A series of case studies, 2003-2007. Washington, D.C.: Borden Institute: Walter Reed Army Medical Center; 2008.

55 O’Brien K, Army Training, Doctrine Staff. Tactical combat casualty care: Improvements to tactical combat casualty care (TCCC) and the combat lifesaver (CLS) course. Memorandum. 2010. April 8

56 Pearn J. Militares medici in nummis repraesentati: The heritage of military medicine in coins and medals. Mil Med. 2005;167:6.

57 Peoples GE. Damage control commentary. In: Nessen SC, Lounsbury DE, Hetz SP, editors. War surgery in Iraq and Afghanistan: A series of case studies, 2003-2007. Washington, D.C.: Borden Institute: Walter Reed Army Medical Center; 2008:49-50.

58 Quick guide—provider: Traumatic brain injury, Department of Veterans Affairs. http://www.mirecc.va.gov/docs/visn6/TBI-pocketcards-providers.pdf.

59 Repine TB, Perkins JG, Kauvar DS, et al. The use of whole blood in massive transfusion. J Trauma. 2006;60:S59.

60 Rice MS, Jones OJ. Medical operations in counterinsurgency warfare: Desired effects and unintended consequences. Military Review. 2010;May-June:47.

61 Science Museum, London http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/objects/display.aspx?id=4304

62 Simmons JW, White CE, Eastridge BJ, et al. Impact of policy change on U.S. Army combat transfusion practices. J Trauma. 2010;69:S75.

63 Tactical combat casualty care guidelines. August 18, 2010.

64 Tourniquet overview. http://www.tourniquets.org/tourniquet_overview.php#historical_perspective.