Coma

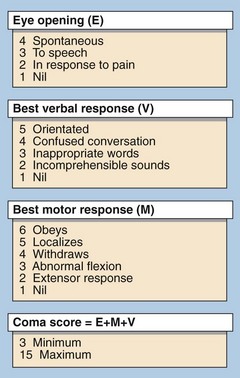

The depth of coma can be defined following clinical examination using a scale such as that in Figure 63.1. This allows clinical staff to establish the severity of the coma and to monitor changes. Obtaining the correct diagnosis is paramount. To this end the most valuable information is usually obtained from the clinical history, but frequently a reliable history is not available.

Differential diagnosis of coma

A helpful mnemonic in the diagnosis of the unconscious patient is given in Figure 63.2. However, within each of these categories described there are many possible causes. The first priorities in treating an unconscious patient are to ensure that airways are clear and that breathing and circulation are satisfactory.

Cerebrovascular accident

Where coma of cerebrovascular origin is suspected a CSF examination may show the presence of blood and will help to differentiate a subarachnoid haemorrhage from cerebral infarction (see p. 130). When available, imaging with a CT scan or MRI is preferable.

Infectious causes

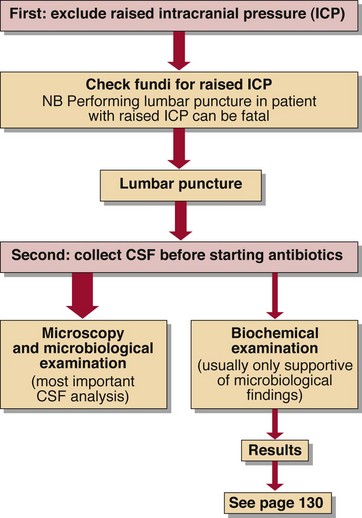

Meningitis (bacterial and viral) and encephalitis (viral) can both lead to coma. Meningococcal meningitis has a high mortality, especially in children. Diagnosis is of great importance and CSF specimens should be obtained before antibiotic therapy is commenced (Fig 63.3). The usual findings are:

Metabolic causes

The brain is acutely sensitive to failure in metabolic homeostasis, and a wide range of disorders can give rise to disorientation and later coma. Many of these cases can be corrected rapidly by treatment and thus their early diagnosis is mandatory. The most common forms are shown in Figure 63.2.

Drugs and poisons

A wide variety of drugs and poisons can give rise to coma if taken in sufficient dose. In very few cases are there specific clinical signs. Exceptions are the pinpoint pupils of opiate poisoning for which the specific antagonist naloxone is effective in restoring consciousness, and the divergent strabismus (Fig 63.4) associated with tricyclic antidepressant overdose. In most cases of drug or poison-induced coma, conservative therapy is all that is required to maintain vital functions until the substance is eliminated by metabolism and excretion. The best specimen to analyse for diagnosis is urine. Where drugs such as phenytoin or theophylline are suspected, plasma levels should be measured on admission and thereafter until they fall to therapeutic levels (see pp. 118–119).

Brain death

The diagnosis of brain death is made using criteria outlined in Table 63.1, which includes arterial blood gas analysis. Where measurable sedative drugs have been used (for example in ITU) there must be biochemical confirmation that these drugs are no longer present.

Table 63.1

Criteria for confirming brain death

ALL BRAIN-STEM REFLEXES ARE ABSENT

The pupils are fixed and unreactive to light

The pupils are fixed and unreactive to light

The corneal reflexes are absent

The corneal reflexes are absent

The vestibulo-ocular reflexes are absent – there is no eye movement following the injection of 20 mL of ice-cold water into each external auditory meatus in turn

The vestibulo-ocular reflexes are absent – there is no eye movement following the injection of 20 mL of ice-cold water into each external auditory meatus in turn

There are no motor responses to adequate stimulation within the cranial nerve distribution

There are no motor responses to adequate stimulation within the cranial nerve distribution

There is no gag reflex and no reflex response to a suction catheter in the trachea

There is no gag reflex and no reflex response to a suction catheter in the trachea

No respiratory movement occurs when the patient is disconnected from the ventilator long enough to allow the carbon dioxide tension to rise above the threshold for stimulating respiration (PCO2 must reach 6.7 kPa)

No respiratory movement occurs when the patient is disconnected from the ventilator long enough to allow the carbon dioxide tension to rise above the threshold for stimulating respiration (PCO2 must reach 6.7 kPa)

The diagnosis of brain death should be made by two experienced doctors, one of whom should be a consultant and the other a consultant or specialist registrar. The tests are usually repeated after an interval of 6–24 hours, depending on the clinical circumstances, before brain death is finally confirmed.