9 Colorectal disorders

Ulcerative colitis

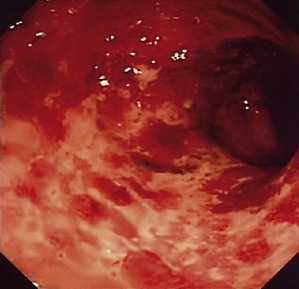

This is a chronic, inflammatory disease which involves the whole or part of the colon. Colitis may be caused by a number of different conditions, including infection (Boxes 9.1 and 9.2). Ulcerative colitis is common in the UK, North America and Scandinavia, with a slightly increased incidence of familial occurrence. The inflammation is confined to the mucosa and nearly always involves the rectum (Fig. 9.1).

Aetiology is unknown but immunological, dietary and genetic factors and transmissible agents may be involved. The inflammatory changes are most marked in the rectum and spread to a varying degree proximally into the colon. The disease does not extend proximal to the ileocaecal valve. The histological features are shown in Box 9.3.

Diverticular disease

The main manifestations of diverticular disease are listed in Box 9.5.

Treatment

• Uncomplicated diverticular disease may respond to bulking agents (e.g. ispaghula). If pain or complications occur, resection of the affected segment may be considered. Barium enema assists assessment of the extent of bowel to be resected (Fig. 9.3)

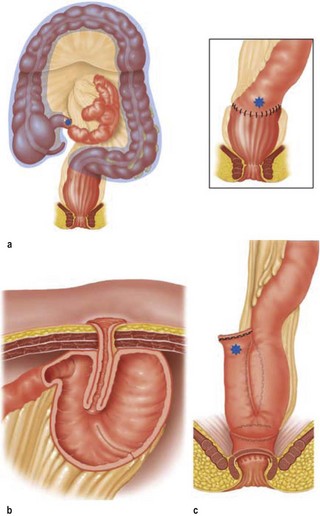

• Acute diverticulitis requires bed rest, fluids only, and antibiotics (e.g. cefuroxime, metronidazole). Perforated diverticulum requires laparotomy and resection of the perforated bowel. Rejoining the bowel is risky in the presence of peritonitis and the proximal bowel is usually brought out as an end colostomy (Hartmann’s procedure: resection of the sigmoid colon, oversewing of the rectal stump and LIF end colostomy). This may be performed laparoscopically

• Haemorrhage – rectal bleeding due to diverticular haemorrhage can be profuse and require significant transfusion. The distinction between upper and lower GI bleeding can be difficult (Table 9.1) and OGD is usually required to exclude UGIH. Most diverticular bleeds stop spontaneously. Urgent colonoscopy and angiography ± embolisation may be required. If haemorrhage is life-threatening, a colectomy with ileostomy may be considered.

| Upper gastrointestinal | Colonic | |

|---|---|---|

| Haematemesis | Common | Never |

| Stool | Melaena, or dark blood with clots, fresh blood for a brisk major bleed | Bright red bleeding or dark red with clots |

| Plasma urea | Elevated (due to partial digestion of blood) | Normal |

| Pain | No | No |

Diverticular mass/abscess/fistula (Table 9.2)

Table 9.2 Hinchey grading system: classification of perforations of colon due to diverticular disease (and current management strategy)

| Grade | Definition | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| I | Localised abscess | Medical ± radiological |

| II | Pelvic abscess | Medical + radiological |

| III | Purulent peritonitis | Surgical (laparoscopic or open) |

| IV | Faeculent peritonitis | Surgical (open) |

Colonic polyps

Classification of the different types of polyps is shown in Box 9.6. Many benign large bowel polyps are associated with a number of different conditions, many of which have a genetic component. The most common and important neoplasm is an adenoma arising from the glandular or epithelial cells. Polyps most often have a stalk but flat lesions can occur.

Colorectal cancer

Staging

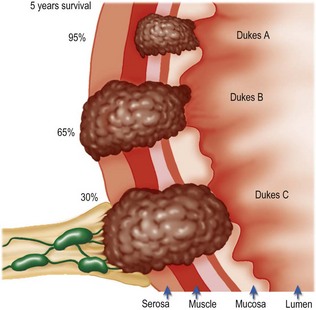

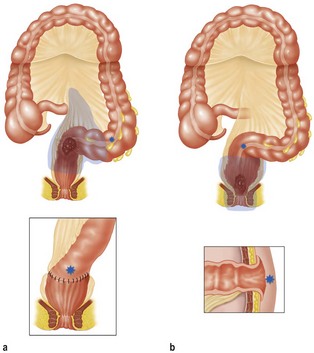

A conventional method of staging is the Dukes classification (Fig. 9.4):

• A: cells are confined to the mucosa (5-year survival: 95%)

• B: the tumour has extended through all muscle layers (5-year survival: 65%)

• C: lymph node metastases (5-year survival: 30%)

• D (added to Dukes later on): disseminated metastatic disease (5-year survival is now approaching 20% after surgery).

Many centres now use the TNM staging system as a basis for further decisions about adjuvant radio- or chemotherapy (Box 9.7).

Clinical features

Treatment

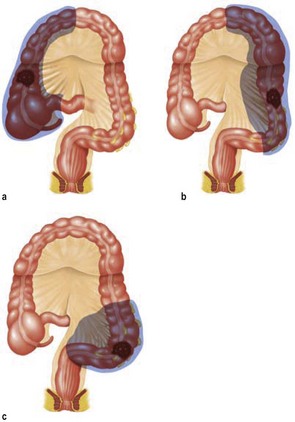

Colonic carcinoma is treated by surgery (Fig. 9.5) following preoperative staging with CT scans, colonoscopy to exclude metachronous lesions and general fitness for a general anaesthetic. Bowel preparation is usually mechanical with Picolax or Klean-Prep. Colostomy is avoided.

Rectal carcinomas present different preoperative problems and many patients are entered into trials of adjuvant radio/chemoradiotherapy (e.g. the CRO7 trial comparing preoperative radiotherapy and selective postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer). Radiotherapy may be either a short course (5 days) or a long course, depending on stage of tumour, usually assessed by MRI of the rectum. Rectal cancers are surgically treated by anterior resection or abdominoperineal excision (Fig. 9.6). Complications of colorectal surgery are listed in Box 9.9.

Anal and perianal disorders

Clinical examination is an essential feature of assessment of any patient with symptoms attributable to the anal canal and the rectum must always be examined to make certain that the underlying cause is not proximal. The causes of rectal bleeding as a symptom are shown in Box 9.10. The patient is placed in the left lateral position. The examination comprises three components: inspection, palpation and endoscopy (sigmoidoscopy and proctoscopy). If investigation is impossible in the outpatients department, it can be done under anaesthetic (EUA), particularly when pain and discomfort prevent digital palpation.

Further investigations include flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy and intraluminal ultrasound (which provides accurate information about the anal canal and sphincters and localising perianal sepsis/fistulas). MRI scanning can accurately identify primary and secondary fistulous tracks and abscess and may provide additional data about the extraluminal spread of rectal cancer (particularly useful in patients with early rectal cancer, who are being considered for TEMS.) Fistulography and evacuation proctography are rarely used in general practice. Examination of pus may be helpful in determining whether or not anal fistula is present (Table 9.3). Anorectal physiology studies are widely used to evaluate patients with faecal incontinence. These tests measure the anal canal pressure, the anorectal reflex, the ability to expel a faecal bolus and electromyographical assessment of the external sphincter and its response to pudendal nerve stimulation.

| Condition | Examination | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Acute abscess | Standard cultures | Intestinal organisms – ? fistula |

| Gonorrhoea | Fresh swab and culture | Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

| Syphilis | Dark ground examination | Spirochaetes |

| Fungal infection | Direct microscopy of scrapings of perianal skin | Pathogenic organism |

| Culture | ||

| Tuberculosis | Histopathological examinationCulture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Caseating granulomasOrganisms on Ziehl–Neelsen stainOrganism and sensitivity |

Haemorrhoids

These are engorgements of the haemorrhoidal venous plexuses with redundancy of their coverings. The anal cushions may remain in their usual position in the anal canal (first degree), descend to involve the skin of the distal anal canal so that they prolapse on defecation but reduce spontaneously (second degree), or become of such a size that they are always partly outside the anal canal (third degree). Classical positions are the left lateral, right posterior and right anterior positions, although secondary haemorrhoids can occur in between these anatomical sites. The diagnosis of haemorrhoids is shown in Table 9.4. Constipation and straining at the time of defecation may be a factor in the development of haemorrhoids. In women, pregnancy is a common risk factor.

Table 9.4 Conditions related to (and which may be confused with) haemorrhoids

| Condition | Position |

|---|---|

| Anal skin tags | Anal margin |

| Fibrous anal polyps | Line of the anal valves |

| Prolapse of rectum | Similar to haemorrhoids but circumferential |

| Thrombosis in perianal skin (perianal haematoma) | Distal to mucocutaneous junction |

| Fissure | Primarily at the mucocutaneous junction but may have a distal skin tag |

| Benign tumours of the rectum | Within the rectum at sigmoidoscopy |

| Varices | Rare but almost impossible to distinguish |

| Haemangioma | Rare congenital abnormality |

Treatment

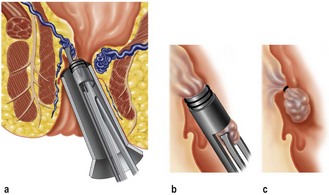

Several treatments are available. Injection sclerotherapy and Barron banding (with or without the use of suction) are treatments used in the outpatient department. Cases requiring general anaesthesia include standard haemorrhoidectomy, THD and, more recently, stapled haemorrhoidopexy. The latter are generally reserved for resistant cases or third-degree haemorrhoids. Manual dilatation of the anus is rarely used for fear of irreversible damage to the anal sphincter. Injection sclerotherapy may need to be repeated. Barron-band ligation (Fig. 9.7) has a serious complication of pain and haemorrhage after the application of the bands. Cryotherapy and lateral anal sphincterotomy are rarely used for the treatment of haemorrhoids today. Haemorrhoidectomy aims to excise as much redundant epithelium and vasculature as possible and may be carried out by a variety of methods.

Perianal sepsis

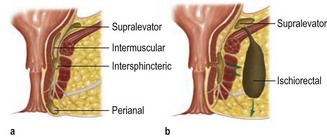

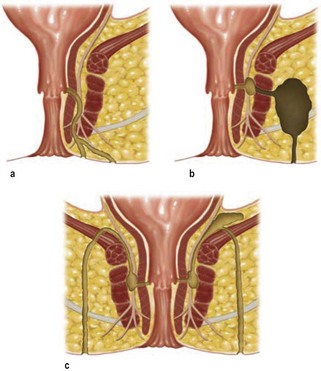

A variety of anal conditions present with suppuration, as shown in Table 9.5. The spread of sepsis begins in the intersphincteric space and may spread vertically, horizontally or circumferentially (Fig. 9.8). Five anatomical sites of abscess are classified into intersphincteric, perianal, intermuscular, supralevator and ischiorectal. The formation of a fistula occurs as a result of pus spreading along a track to emerge distal to the mucocutaneous junction, and an internal and external track is formed. Fistulas are classified according to their intersphincteric/trans-sphincteric nature. Other types of fistula include superficial, suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric (Fig. 9.9).

| Condition | Usual finding |

|---|---|

| Non-specific infection | Acute abscess |

| Fistula in ano | |

| Tuberculosis | Chronic infection |

| Occasionally fistula | |

| Crohn’s disease | Chronic intractable infection |

| Complex fistula | |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | Skin abscesses |

| Anal canal rarely if ever involved | |

| Skin sepsis | Usually Staphylococcus aureus |

| Abscesses are often multiple | |

| Trauma | External: sexual intercourse; accidental injury |

| Internal: foreign body (ingested bone) | |

| Intrapelvic sepsis | Diverticular disease |

| Crohn’s disease | |

| Sepsis in developmental cysts | Usually dermoid cysts |

| Malignant disease | Sepsis is an uncommon complication |