Chapter 18 COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING

BACKGROUND

The third millennium is witnessing the emergence of preventive medicine as a cornerstone in our concept of health. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major health concern (Chapter 17), and one that fits the criteria of a preventable disease. Approximately two-thirds of the cases involve average-risk men and women, with a sharp increase of its incidence starting from the fifth decade of life.

Detection and removal of colonic adenomas, the non-invasive neoplasm that are the precursors of CRC, could prevent up to 90% of CRC cases. The transition process between adenomas to carcinoma is estimated as 5–10 years and that of normal mucosa thorough adenoma to adenocarcinoma as 15–20 years. This interval provides a unique window of opportunity for screening and effective interventions to reduce CRC-associated mortality. The respective curative benefits that can be gained by detecting CRC at early stages, e.g. node-negative stages I and II, are as high as 90% and 75%, respectively, with surgery alone, while the 5-year survival rate is close to zero for metastatic CRC.

FAECAL OCCULT BLOOD TESTING

Support for the ability of annual FOBT to reduce the mortality from CRC emerged from several large prospective randomised trials. Mortality was reduced by 15%–33% if the test was done yearly, and when positive results were followed by colonoscopy. A meta-analysis that pooled the results of these studies estimated a 16%–23% reduction in CRC mortality. The estimated FOBT sensitivity for cancer ranges between 30% and 90% depending upon the test used. The major limitation of FOBT is its low sensitivity as a screening test, since some carcinomas and most adenomas do not bleed. Only 24% of advanced neoplasia cases had a positive FOBT result on the three consecutive days’ samples obtained prior to bowel preparation. Proper FOBT testing requires examining three different bowel movements. Prerequisite compliance is difficult to achieve from both patients and physicians. In addition, the test gives an indirect result; hence, individuals who test positive have to undergo colonoscopy to confirm the presence of polyps, cancer or other pathology. Survival benefit may therefore reflect the benefit of colonoscopy, for detecting incidental lesions including those of subjects with false positive FOBT results. Lastly, upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract sources of occult bleeding, NSAID use or false positive results due to dietary ingredients may lead to unnecessary colonoscopies. There is often a low referral rate of patients with positive FOBT screening findings.

FOBT testing has no merit as a single test. It should definitely not be done when a patient has overt rectal bleeding (see Chapter 20) or any alarm symptoms. In such cases colonoscopy must be performed.

SIGMOIDOSCOPY

The main drawback of sigmoidoscopy is the limit of its extension, which is up to the splenic flexure at best. Unfortunately, the distance is often significantly shorter. Sensitivity actually depends on the varied experience of the examiners, and on patient discomfort, two factors that have a major impact on the depth of insertion and adequacy of mucosal inspection. Even in the hands of expert endoscopists, the sigmoidoscope was found to traverse the sigmoid colon in only 66% of cases. For more than 50% of proximal advanced lesions (i.e. advanced adenoma or carcinoma) there were no lesions in the distal colon, so those would have been missed by sigmoidoscopy. Sigmoidoscopy is even less rewarding in subjects aged 65–75 years, as a proximal shift of neoplasia in this age group is suggested.

COLONOSCOPY

Colonoscopy is the gold standard procedure to identify colorectal neoplasia. Skilled gastroenterologists perform the examination after a cathartic bowel preparation. Using back-to-back colonoscopies, it was shown that the sensitivity of a single colonoscopy is about 90%–95% for cancers and large adenomas and 75% for polyps <1 cm. The detection rates for adenomas ≥10 mm, 5–10 mm and 1–5 mm were found to be 98%, 87% and 74%, respectively. Colonoscopy miss rates are related to the skills of the endoscopist, withdrawal technique and, in particular, withdrawal time that reflects the time spent to inspect the colon. Although there are no published prospective studies on direct reduction of CRC mortality by primary screening colonoscopy, there is a large body of evidence to support it. The National Polyp Study has demonstrated a 76%–90% decrease in the incidence of CRC at 6 years after the index colonoscopy and polypectomy, compared with several appropriately selected control groups. A prospective 13-year follow-up demonstrated a relative risk of 0.2 for CRC in subjects who underwent colonoscopy with polyp removal compared with the control group. The prevalence of CRC in asymptomatic patients being screened aged 50–75 years in the USA is approximately 1%. Overall, the findings support the use of colonoscopy rather than sigmoidoscopy for screening in this age group.

RISK STRATIFICATION AND CURRENT SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS

Screening for colonic neoplasia is important for individuals who are free of any signs or symptoms suggestive of CRC. A full colonoscopy is absolutely indicated in the presence of alarm symptoms. A key element for tailoring the most appropriate screening programme relies on the individual’s level of risk, which is based primarily on age, as well as on personal, family and medical history. This risk status determines when screening should be initiated, at what frequency and by which modality. Risk stratification can be determined by asking pertinent questions aimed at uncovering the risk factors for CRC (Table 18.1):

TABLE 18.1 Risk factors for colorectal cancer that mandate colonoscopy as the screening tool

| Genetic disorders |

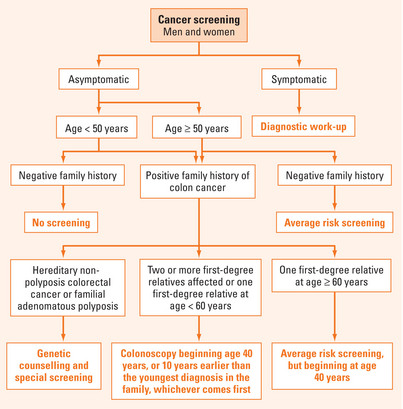

Asymptomatic individuals with any risk factors for CRC are then re-classified into ‘moderate-risk’ (personal and/or family history of CRC or adenoma), or ‘high risk’ for CRC (e.g. familial neoplastic syndromes or inflammatory bowel disease). Current CRC screening recommendations (based on recent professional guidelines) are shown in Figure 18.1.

FIGURE 18.1 Colorectal cancer screening recommendations.

Based on Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale—Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology 2003; 124:544–60.

CRC screening in moderate-risk populations

This subpopulation is defined by a personal or family history of adenoma/CRC. Professional guidelines recommend the following guidelines (Table 18.2):

TABLE 18.2 Guidelines for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in a moderate-risk group

| Colonoscopy* starting at age 40 years or 10 years younger than the earliest diagnosis if: |

High-risk groups for CRC screening

This group should undergo more intensive surveillance with colonoscopy only (see Table 18.1). These guidelines do not include screening for cancers outside the colon and, for the genetic syndromes, recommendations are based on phenotype only (Table 18.3).

TABLE 18.3 Guidelines for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in high-risk groups

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | Annual sigmoidoscopy, beginning at age 10–12 years* |

| Hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer | Colonoscopy every 1–2 years beginning at age 20–25 years, or 10 years earlier than the youngest age of cancer associated with HNPCC (gastric, ovarian, uterine, small intestine) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Colonoscopy every 1–2 years after 8 years of disease in patients with pancolitis or after 12–15 years in left-sided colitis. Biopsies should be taken every 10 cm in all four quadrants with additional sampling of strictures or any mucosal irregularities |

* This recommendation holds true based on phenotype only (without a definite genetic mutation).

SURVEILLANCE OF INDIVIDUALS AT INCREASED RISK

Emerging screening modalities

Faecal DNA test

A stool-based molecular analysis of DNA markers in exfoliated colonocytes that are regularly shed in the stool. The rationale of the examination is that normal colonocytes are sparse and apoptotic (e.g. contain ‘short’ DNA fragments), while neoplastic colonocytes are abundant and harbour high molecular weight DNA (‘long DNA’). Since CRC is a disease of mutations that occur as tissue evolves from normal to adenoma to carcinoma, these mutations can be detectable in the stool. Advantages of this test over the other screening modalities are their non-invasive nature and lack of bowel preparation or any dedicated procedural time. Testing can be performed on mailed-in specimens, whereby geographic access to stool screening is essentially unimpeded. Initial studies based on either single mutation or panels of genetic markers had a sensitivity of 91% and 82% for CRC and large adenomas, respectively, but controlled studies demonstrated less favourable results. Long DNA was the most frequent neoplastic marker in the stool. The most prevalent genetic alterations were mutations in K-ras and p53 genes, followed by microsatellite instability (MSI) and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene mutations. The test seems promising with considerably higher sensitivity and specificity than FOBT, but has not yet been validated as a screening tool in large-scale prospective trials. At present, the high cost of faecal DNA testing is a major obstacle that reduces its cost-effectiveness. There is a promising future for this approach if sensitivity could be increased by additional markers (e.g. methylation) and if cost could be reduced.

Chromoendoscopy

A technique that consists of staining the mucosal surface of the GI tract in order to enhance the diagnostic yield of endoscopy. The main purpose is to screen for neoplastic or preneoplastic lesions (in particular flat or depressed lesions) and to direct endoscopic biopsies. Indigo carmine is a contrast stain that accumulates in pits and valleys between cells highlighting the mucosal architecture that becomes even more apparent with the use of magnification and/or high-resolution endoscopy. The technique only requires a special spraying catheter, making it simple and relatively inexpensive. Its only disadvantage is that it prolongs the overall procedural time. Currently, chromoendoscopy is reserved for high-risk subjects (i.e. patients with a personal history of neoplasia, inflammatory bowel disease or familial neoplastic syndromes).

New technologies on the horizon

Self-propelling self-navigating skill-independent colonoscopy

(The Aer-O-Scope™ GI View, Israel) This new disposable colonoscope is a skill-independent, anaesthesia-free, self-propelling, self-navigating miniaturised endoscopic device that moves along the entire length of the colon, transmitting video pictures of the colonic mucosa. This disposable product is based on a miniaturised self-propelling, self-navigating locomotion mechanism that contains a digital camera. The device is supplied with electricity, air, water and suction via a thin supply cable, which it drags behind it. The device has a novel optical system enabling a 360° view, and hence may decrease the polyp miss rate, particularly behind folds. So far the device has proven safe, without any complications in more than 60 subjects.

Bernstein CN. Ulcerative colitis and low-grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:950-956.

Levine JS, Ahmen DJ. Clinical Practice. Adenomatous polyps of the colon. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2551-2557.

Lindor NM, Petersen GM, Hadley DW, et al. Recommendations for the care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to Lynch syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1507-1517.

Rex DK. Maximizing detection of adenomas and cancers during colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2866-2877.

Schoen RE, Weissfeld JL, Pinsky PF, et al. Yield of advanced adenoma and cancer based on polyp size detected at screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1683-1689.

Walsh JM, Terdiman TP. Colorectal cancer screening; scientific review. JAMA. 2003;289:1288-1296.

Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale—Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544-560.

Winawer S, Zauber AG, Fletcher RH, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1872-1885.