Chapter 17 COLORECTAL CANCER

RISK FACTORS

Environmental and genetic factors can increase the likelihood of developing colorectal cancer (CRC) (Table 17.1). Although inherited susceptibility most strikingly increases the risk, the majority of CRCs are sporadic. Age is a very important risk factor. It rarely occurs before the age of 40, and the incidence begins to increase significantly in the sixth decade, with the highest rate between 65 and 75 years. The incidence rate is higher in industrialised regions, higher in African American than in whites, and it is nearly equal for males and females (M:F ratio1.3:1.0 for rectal tumours).

| Risk factor | Examples | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic disorders | Familial adenomatous polyposis | I |

| Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer | I | |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | I | |

| Hyperplastic polyposis | I | |

| Cowden’s syndrome | I | |

| Juvenile polyposis syndrome | I | |

| Personal history of CRC or adenoma | I | |

| Family history of CRC or adenoma | I | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease | I |

| Medications | NSAIDs, aspirin, calcium, vitamin D, statins, hormone replacement therapy (in postmenopausal women) | D |

| Endocrine disorders | Diabetes mellitus | I |

| Insulin resistance | I | |

| Acromegaly | I | |

| Obesity | I | |

| Gastrin | I | |

| Surgical interventions | Cholecystectomy | I |

| Ureterocolic anastomoses | I | |

| Environmental factors | Smoking | I |

| Moderate physical activity | D | |

| Healthy diet (low calorie, rich in fruits and vegetables with low animal products) | D | |

| Alcohol (moderate and high amount) | I |

D = decrease risk for CRC; I = increase risk for CRC; NSAIDs = non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

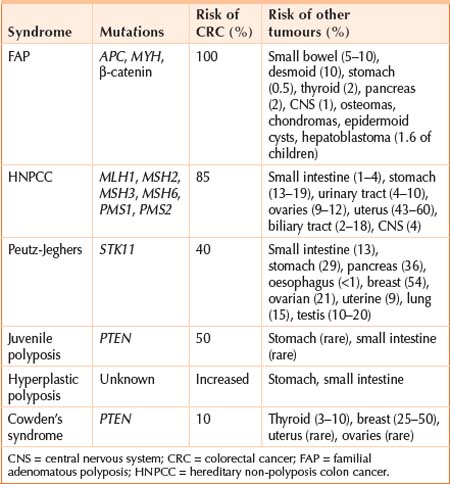

GENETICS

MULTI-STEP MODEL OF CRC

Specific genetic mutations

The APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene on chromosome 5 is the most critical gene in the early development of CRC. Somatic mutations in both alleles are present in 80% of sporadic CRCs. Most sporadic CRCs with wild-type APC have mutations in other genes of the Wnt signalling pathway, mostly in β-catenin.

Mismatch repair genes

Mismatch repair genes are the hallmark of HNPCC, but are also found in 15% of sporadic CRC. They are involved in correcting base mismatches and small insertions or deletions that occur during DNA replication. MSH2 and MLH1 are the most important ones followed by MSH6, MSH3, PMS1 and PMS2. The prognosis in this setting is better and the response to chemotherapy is less favourable.

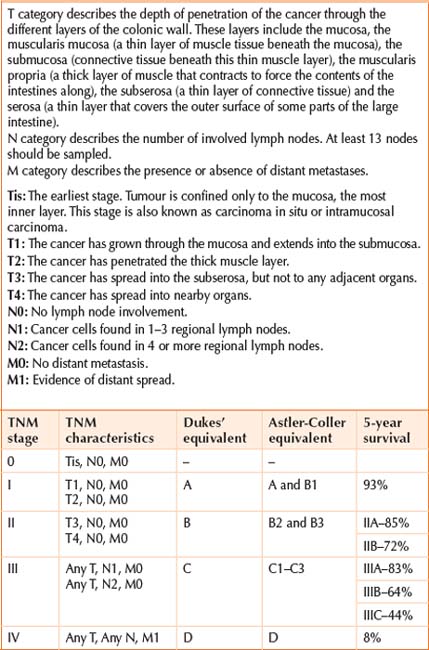

DIAGNOSIS

Pathology

Staging and prognosis

THERAPY

The development of interdisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic strategies has led to a moderate decline in mortality (2% per year). This is attributed to increased public and professional awareness, assimilation of recommended life style modification, screening and removal of polyps, better surgical techniques, better staging and use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Surgery will cure 50% of patients. More than 40% of the diagnosed patients will develop metastatic disease. Survival is directly related to the extent of disease at the time of diagnosis. If metastasis has occurred to distant sites, the 5-year survival rate is 5%–7%, but it increases to >90% when the cancer is diagnosed early. Long-term survival for patients with resectable liver and lung metastasis can be as high as 30%–40% with aggressive and novel therapy. Early detection of this surgically curable disease and preventive interventions (e.g. polypectomy) is the single best modality. There is now compelling evidence that colon screening of asymptomatic, average risk individuals over 50 years of age can reduce CRC mortality by 15%–90%, depending on the screening programme (see Chapter 18).

Adjuvant therapy

Fluorouracil

Has been used since 1957 and remains the primary chemotherapeutic agent, with a response rate of 10%–12%. In 1990, an NIH consensus panel recommended adjuvant fluorouracil based chemotherapy in all stage III CRC. This was based on a large study in which fluorouracil and levamisole (an anthelmintic and immunostimulant agent), given for 12 months, achieved a 41% reduction in the relapse rate and a 33% decrease in mortality. Similarly, combining fluorouracil with folinic acid (calcium folinate) was shown to be effective as adjuvant therapy in stage III disease, and selected stage II cases. Fluorouracil and levamisole (given for 12 months) was as effective as fluorouracil and folinic acid (for 6 months), but more toxic. Consequently, the latter combination became the standard of care.

New biological agents

Cetuximab

A chimeric IgG monoclonal antibody that blocks epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) associating with its ligand, thus inhibiting the downstream signal transduction and preventing cell growth, differentiation and metastasis. It causes a typical acne-like rash, which is associated with a positive response.

Treatment of rectal cancer

Surgery is recommended following chemoradiotherapy.

Fluorouracil and folinic acid are given for an additional 4 months after successful surgery.

In cases when surgery was performed first, postoperative treatment includes fluorouracil (continuous infusion or bolus) during pelvic irradiation followed by four cycles of maintenance fluorouracil and folinic acid.

American Joint Committee on Cancer. Manual for staging of cancer, colon and rectum, 6th edn. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002.

Kwak EL, Chung DC. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: an overview. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2007;6:340-344.

Levine JS, Ahnen DJ. Clinical practice. Adenomatous polyps of the colon. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2551-2557.

Pfister DG, Benson AB3rd, Somerfield MR. Clinical practice: surveillance strategies after curative treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2375-2382.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:41-52.