Is there a place for collective bargaining in nursing?

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Identify the milestones in the history of collective bargaining.

• Compare traditional and nontraditional collective bargaining.

• Identify examples that indicate an employer’s position on the role of professional nurses as it impacts practice.

• Identify conditions that may lead nurses to seek traditional or nontraditional collective bargaining.

• Identify the positive and negative aspects of traditional and nontraditional collective bargaining.

• Discuss the benefits of collective bargaining for professional groups.

• Discuss the impact of the silence of nurses in public communications and the public’s perception of nurses.

• Identify barriers to the control of professional practice.

You will soon be accepting your first position as a registered nurse (RN). You will be adjusting not only to a new role but also to a new workplace. Even in these times of dramatic change in health care, many of you will start your career in a hospital. In fact, the demographics about nurses show that

▪ Approximately 61% of nurses in practice are providing care in hospitals (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). Additionally, registered nurses are providing direct patient care in settings such as outpatient care settings, private practice, health maintenance organizations, primary care clinics, home health care, nursing homes, hospices, nursing centers, insurance and managed care companies, etc. (Potter, Perry, Stockert, & Hall, 2013; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016) in which care that was hospital-based in the past is now provided in these alternative settings.

▪ The hospital is also the most common employer of graduate nurses in their first year of practice; more than 72% of new graduates were working in a hospital in their first year of employment (NCSBN, 2015).

▪ Employment of registered nurses is projected to grow 16% from 2014 to 2024, faster than the average for all occupations. Growth will occur for a number of reasons, including an increased emphasis on preventative care; growing rates of chronic conditions, such as diabetes and obesity; and demand for health care services from the Baby Boomer population, as they live longer and more active lives (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016).

As you begin to interview for your first position in your career as a professional RN, there is no doubt you will find yourself both excited and anxious. Your prospective employer will assess your ability to think critically and to perform at a professional level in the health care setting. The potential employer will ask, “Is this applicant a person who will be able to contribute to the mission of the organization and to the quality of health care offered at this organization?”

While the employer assesses your potential to make a contribution, it is equally important that you remember that an interview is a complex two-way process. You will, of course, be eager to know about compensation, benefits, hours, and responsibilities. These are very tangible and immediate interests. However, these are not likely to be the best predictors of satisfaction with your practice over time, as the ability to practice your profession as defined by licensure and education will be the foundation leading to job satisfaction and professional fulfillment.

You should be prepared to assess the potential employer’s mission and ability to support your professional practice and growth. It is extremely important that you gain essential information about the organization, its mission, and its culture. It is easy to overlook very significant organizational issues that will ultimately affect your everyday practice of nursing when your primary focus is on becoming employed and on wondering whether you will succeed in this first professional role. Thomas (2014) identifies several questions to keep in mind: What is the management style of the company? How is patient satisfaction measured here, and what are the most recent findings? What would you say are the top two to three qualities of the most successful nurses currently working here? Additionally, it is important to use the 2015 Code of Ethics for nursing to guide your questions about the role of the staff registered nurse in decision making related to the practice of nursing in the facility. “Making decisions based on a sound foundation of ethics is an essential part of nursing practice in all specialties and settings…” (American Nurses Association, 2015a).

Hospital structures and governance policies can have a dramatic influence on the effectiveness of a registered nurse and how he or she can fulfill obligations to patients and families. Registered nurses have defined the discipline of nursing as a profession, and, as members of this profession, they must have a voice in and control over the practice of nursing. When that voice and control are not supported in the work setting, conflicts most likely will arise. In some states, nurses have made a choice to gain that voice and assume control of their practice by using a traditional collective bargaining model, commonly known as a labor union. In other states, particularly those that function under the right-to-work regulations, nurses attempt to control practice through interest-based bargaining (IBB), which is a nontraditional approach to collective bargaining that is used to accomplish the provision of a voice and control over practice (Budd et al., 2004) (Box 18.1). In some states nurses use both models to meet the needs of their diverse membership.

When did the Issues Leading to Collective Bargaining Begin?

Since World War II, there have been phenomenal advances in medical research and the subsequent development of life-saving drugs and technologies. The introduction of Medicare and Medicaid programs in 1965 provided the driving force and the continued resources for this growth. This initiative opened access to health care for millions of Americans who were previously disenfranchised from the health care system.

The explosion in knowledge and technology, coupled with an expanded population able to access health care quickly, increased the demands on the health care system and many of the providers in that system. These advances required nursing to adapt as the complexity of health care and the number of patients accessing this care continued to increase. For example, at the time when the acuity of hospitalized patients increased because of shorter lengths of stay, organizations were responding to cost containment demands by downsizing the number of staff members. As more patients had access to all services in the health care system, the number of care hours available for each patient decreased, because fewer staff per patient were being hired. Overall, patients were sicker when they entered the system. Yet they were moved more quickly through the acute care setting because of such innovations as same-day admissions, same-day surgery, increased discharge to long-term care settings and early discharge. Add to these changes the periodic shortages of nurses prepared for all levels of care, the increased use of unlicensed assistive personnel to provide defined, delegated nursing care, and growing financial pressures on the health care system, and tensions became understandably high.

The time between 2000 and 2013 also brought pressures on registered nurses, as the safety of hospitalization became a paramount concern among both patients and health care staff. The publication To Err Is Human (Institute of Medicine, 2000, p. 31) stated that “Based on the results of the New York Study, the number of deaths due to medical error may be as high as 98,000 [yearly].” With registered nurses being at the bedside of acute care patients, their involvement in identifying and/or committing medical errors is high. Ensuring this staff has the appropriate resources to provide safe care is an issue that registered nurses need to address directly with the management of the facility and/or the collective bargaining agent for that hospital/organization. Enormous financial challenges confront health care institutions. As a registered nurse working in the health care industry, you will encounter and use newly developed and very costly health care technologies. At the same time, you will experience, firsthand, the impact of public and private forces that are focused on placing restraints on cost and reimbursement for a patient’s care.

Adding to these concerns regarding safe care, new technologies, and potential staff shortages was the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010 (commonly referred to as the Affordable Care Act [ACA] or Obamacare) (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016). A significant aspect of this act is the fact that it created the requirement for almost every person in this country to be covered by some form of health care insurance, thereby increasing the numbers of people who could/would present for care from the various health care facilities.

As a professional RN, you are at the intersection of these potentially conflicting forces. For you, these forces will be less abstract; they are not just important concepts and issues facing a very large industry. As a nurse, these concepts and forces are patients with names, faces, and lives valued and loved within a family and a community. You are responsible for the care you provide and for advocating on behalf of these patients and—as you will soon discover—the health of the health care industry.

As a registered nurse, you will become familiar with how, when, and why events occur that adversely or positively affect the patient and the health of the organization. This places you in a unique position to take an active lead in developing solutions. These solutions must be good for patients and for your organization. During your interview for potential employment, while you are busy assessing the potential employer’s mission and support of your practice and growth, it is easy to overlook those significant organizational attributes that will ultimately affect your everyday practice of nursing. Therefore, during your interview it would be important for you to ask those questions identified in the beginning of this chapter, particularly those that address the ethical practice of registered nurses.

The Evolution of Collective Bargaining in Nursing

In the early 1940s, 75% of all hospital-employed registered nurses worked 50 to 60 hours a week and were subject to arbitrary schedules, uncompensated overtime, no health or pension benefits, and no sick days or personal time (Meier, 2000). In 1946, the American Nurses Association (ANA) House of Delegates unanimously approved a resolution that formally initiated the journey of RNs down the road of collective bargaining. During the period between this resolution and 1999, the constituent organizations of ANA (state associations) were determined to be collective bargaining units for registered nurse members who desired this representation in the workplace. Not all states provided collective bargaining services, so the debate over the acceptance of collective bargaining as appropriate for nurses became a divisive issue in the ANA for decades.

Legal Precedents for State Nursing Associations as Collective Bargaining Agents

The legal precedent that determined that state nursing associations are qualified under labor law to act as labor organizations is the 1979 Sierra Vista decision. The important consequence of this decision that affected nurses was that they were free to organize themselves and not to be organized by existing unions (Kimmel, 2007). Many registered nurse leaders contend that these associations are not only proper and legal but are the preferred representatives for nurses in this country for purposes of collective bargaining. Ada Jacox (1980) suggested that collective bargaining through the professional organization was a way for registered nurses to achieve that collective professional responsibility that is a characteristic of a profession. It was thought by many that the state nursing association was the only safe ground that could be considered as neutral turf on which registered nurses from all educational backgrounds could meet and discuss issues of a generic nature and of importance to all registered nurses. However, as discussed in the section on the history of collective bargaining, it is beginning to appear that the preferred platform for meaningful collective bargaining for the profession is through a structure, such as the National Nurses United (NNU).

Many formally organized unions outside of the ANA have competed for the right to represent nurses. It was the opinion of many nurses that the state nurses associations were the proper and legal bargaining agents and were also the preferred representatives for nurses in this country for purposes of collective bargaining. During the late 1980s, the demand among nurses for representation continued to grow; yet efforts to organize nurses for collective bargaining were being stymied by a decision from the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) that stopped approving the all-RN bargaining units. A legal battle then ensued, with the ANA and other labor unions against the American Hospital Association (AHA). The NLRB issued a ruling that reaffirmed the right of nurses to be represented in all-RN bargaining units.

Seeking a broader base of representation and greater support from the ANA for the collective bargaining program led activist nurses within the ANA to establish the United American Nurses (UAN) in 1999. They believed in the creation of a powerful, national, independent, and unified voice for union nurses. In 2000, the UAN held its first National Labor Assembly annual meeting. The participants in this meeting were staff nurse delegates. In February 2009, the UAN, the California Nurses Association, and the Massachusetts Nurses Association joined forces to form one new union that claims to represent 185,000 members. The new union, called the United American Nurses–National Nurses Organizing Committee, would become a part of the labor movement as an AFL-CIO affiliate union. Shortly after this move, the union was renamed the National Nurses United (NNU) (NNU, 2016).

As has been demonstrated, the representation of registered nurses for collective bargaining continues to change and grow to the point where affiliation with the ANA primarily for this purpose is no longer evident. Collective bargaining outside of ANA has become the route for registered nurses to gain the recognition many believe is essential for the growth of the profession. Others see this as the least effective way to gain recognition and benefits afforded to members of a profession.

Collective bargaining for professional groups (physicians, teachers, professors, scientists, entertainers, pilots, administrators) offers registered nurses another perspective regarding the process of collective bargaining. Identification with these professional groups can certainly help the nursing profession become accepted as a true profession with all the benefits of that identification.

Some of the differences noted between traditional collective bargaining and collective bargaining for professionals are agreeing to take lower wages in exchange for greater fringe benefits, setting a wage floor and then allowing individuals to negotiate for a salary based on individual performance and/or negotiating for merit pay for outstanding performance (DPE Research, 2015). The opportunity to develop a variety of ways to earn wages begins the recognition that, even when bargaining collectively, there are opportunities to be compensated for significant differences in performance.

Collective bargaining for professionals also offers the opportunity to designate how a proposed increase in wages can be used to address other issues that might exist within the professional group. “Registered nurses at a hospital in Michigan turned down a 3% pay raise in favor of a 2% raise and the hiring of 25 additional nurses in an effort to offer better, more professional patient care” (DPE Research, 2015, p. 5).

Who Represents Nurses for Collective Bargaining?

Traditional and Nontraditional Collective Bargaining

The national professional organization for nursing is the ANA, with its constituent units, the state, and territorial nursing associations. Through its economic security programs, the ANA recognized state nursing associations as the logical bargaining agents for professional nurses, and the states have been the premier representatives for nurses since 1946! These professional associations are indeed multipurpose; their activities include economic analyses, provision of related education, addressing nursing practice, conducting needed research, and providing traditional as well as nontraditional collective bargaining, lobbying, and political action.

The creation of the UAN by the ANA strengthened their collective bargaining capacity at a time when competition to represent nurses for collective bargaining was growing. The UAN was established in 1999 as the union arm of the ANA with the responsibility of representing the traditional collective bargaining needs of nurses. At the same time, a relatively new approach to collective bargaining was being developed and introduced into the labor market. This approach is a nontraditional process referred to as interest-based bargaining (IBB) or shared governance (Brommer et al., 2003; Budd et al., 2004). This is a nontraditional style of bargaining that attempts to solve problems and differences between labor and management. Although this style of bargaining and mediation will not always eliminate the need for the more traditional and adversarial collective bargaining, many believe this nonadversarial approach to negotiation may be closer to the basic fabric of the discipline of nursing and its ethical code.

The organization that represented IBB, or the nontraditional collective voice in nursing, was the Center for American Nurses (Center). This was a professional association established in 2003, replacing the ANA’s Commission on Workplace Advocacy that was created in 2000 to represent the needs of individual nurses in the workplace who were not represented by collective bargaining. The Center defined its role in workplace advocacy as providing a multitude of services designed to address the products and programs necessary to support the professional nurse in negotiating and dealing with the challenges of the workplace and in enhancing the quality of patient care (The American Nurse, 2010) (Critical Thinking Box 18.1).

In 2007, the American Nurses Association informed the UAN and CAN that they would not be renewing their affiliation agreement (Hackman, 2008). Following this, in 2009, the largest union and professional organization of registered nurses was officially formalized. This organization is the National Nurses United (NNU), and it is an outgrowth of the merger of three individual organizations—the California Nurses Association, the Massachusetts Nursing Association, and the United American Nurses (the former UAN) (Gaus, 2009). This NNU union includes an estimated 185,000 members in every state and is the largest union and professional association of registered nurses in U.S. history (NNU, 2016).

In 2013, what remained of the Center was integrated into the structure of ANA and is now a part of the “products and services …and valuable resources that will directly assist nurses in their lives and careers” (The American Nurse, 2010, para 2).

ANA and NNU: What Are the Common Issues?

Staffing Issues

Staffing issues and policies related to nurse staffing are among the most prevalent topics discussed in any type of negotiation. There is much discussion in both the national and state legislatures regarding proposals aimed at addressing the way in which registered nurses should be staffed to be able to provide safe, as well as quality, patient care. There is also much objection to implementing mandated staffing plans rather than allowing nurses to maintain control over issues related to their professional practice. The Institute of Medicine (2004) completed a study entitled Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses. The results of the study have led to significant recommendations that, if implemented, would begin to address the chronic shortage of registered nurse staff without resorting to mandatory regulations from the legislatures.

Staffing requirements are already mandated by various agencies. For example, Medicare, state health department licensing requirements, and The Joint Commission (TJC) each publish staffing standards that define the need to have sufficient, competent staff for safe and quality care. The ANA has launched a campaign for safe staffing: Safe Staffing Saves Lives, which encourages the establishment of safe staffing plans through legislation (Trossman, 2008). In 2015, the Registered Nurse Safe Staffing Act was introduced to Congress. If passed, Medicare participating hospitals would be required to develop safe staffing plans for each unit in the hospital. The staffing committee would be comprised of registered nurses working in direct patient care (American Nurses Association, 2015b). However, this legislation will need the factors that define safe, quality staffing as the basis for this legislation. It is also clear that staffing is more than numbers and any legislation or policy must include the fact that the registered nurses must demonstrate the competencies for the processes that are needed to provide safe care and to ensure the safety of patients. Please refer to Chapters 17 and 25 for further discussion regarding staffing issues.

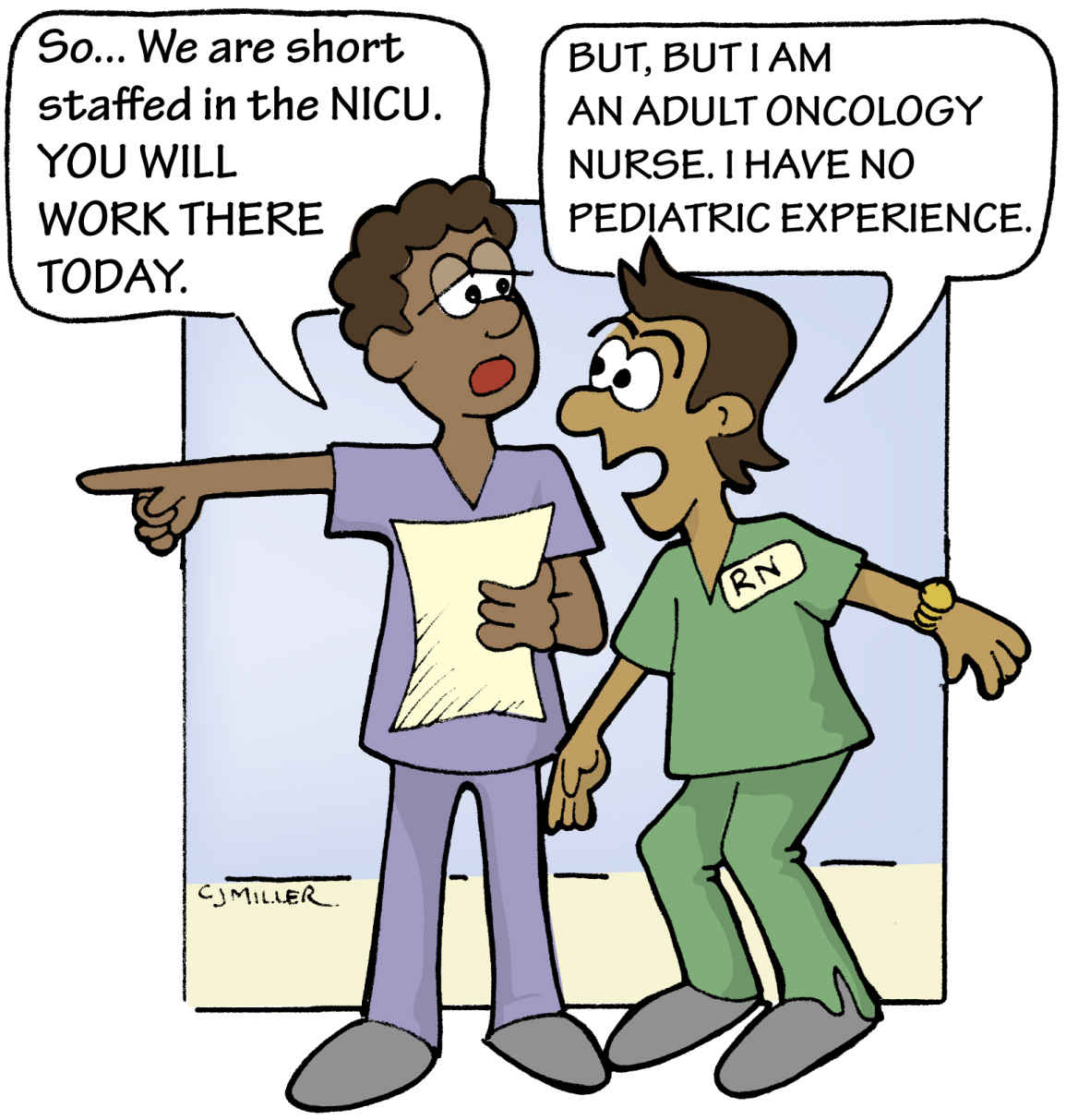

Objection to an Assignment

Professional duty implies an obligation to decline an assignment that one is not competent to complete. RNs cannot abandon their assigned patients, but they are obligated to inform their supervisor of any limitations they have in completing an assignment (Fig. 18.1). Not to inform and not to complete the assignment, or not to inform and to attempt to complete the assignment, risks untoward patient outcomes and resultant disciplinary action up to and including some potential action taken by the board of nursing.

The right and the means for a nurse to register an objection to a work assignment are considered essential elements in a union contract that incorporates the values of a profession as the basis of the contract agreement. This same process must be provided to nurses not represented by a union because nurses are obligated to only provide the care that they are competent to provide. While they are participating in the interview process, registered nurses should ascertain the presence of a written policy regarding objections to an assignment.

Nurses are encouraged to submit reports indicating an objection to the assignment when the assignment is not appropriate. The report should follow the process defined in the contract or facility policy. These same problems should also initiate constructive follow-through by management or staff-management committees to improve the situations described in the reports. Inaction could serve as a basis for a grievance or negotiated change in a union contract or an incident or change in policy in a nonunion environment.

Concept of Shared Governance

Many facilities are implementing a variety of governance models called shared governance, self-governance, participative decision making, or decentralization of management. In its simplest form, shared governance is shared decision making based on the principles of partnership, equity, accountability, and ownership at the point of service (Swihart, 2006). The purpose of shared governance is to involve nurses in decision making related to control of their practice while the organization maintains the authority over traditional management decisions. The concept of shared governance can be a concern to unions representing nurses for purposes of collective bargaining since collective bargaining is also thought to be a governance model that decentralizes aspects of management.

In general, shared governance focuses on clinical practice aspects of the registered nurse staff while collective bargaining has a major focus on work rules/policies, and so forth. While the lines separating practice from work rules is minimal at times, it can be defined by those who are truly interested in achieving outcomes that are best for all parties. The discussion and understanding that must be reached address who or what controls the practice of professional nursing.

The concept of shared governance can be a concern to registered nurses who may feel that participating in shared governance can be a disadvantage to the practicing nurse if this participation is considered an alternative to collective bargaining. Whether greater latitude in decision making could be achieved through collective bargaining is the question to be considered. However, as more facilities are moving toward Magnet certification in which shared governance is a major function, it is recognized that some unionized facilities are also embracing the concepts of Magnet as recognition of the professional aspect of bargaining when representing the profession of nursing. Either way, it is essential that the practice of nursing be defined by nursing and the structure for implementing this practice is in place in each organization where nursing care is delivered.

Clinical or Career Ladder

The clinical ladder, or career ladder, has a place in both traditional and nontraditional styles of collective bargaining (Drenkard & Swartwout, 2005). The clinical ladder was designed to provide recognition of a registered nurse who chooses to remain clinically oriented. The idea of rewarding the clinical nurse with pay and status along a specific track or ladder is the result of the contributions of a nurse researcher, Dr. Patricia Benner. Her descriptions of the growth and development of nursing knowledge and practice provided the basis for a ladder model that can be used to identify and reward the nurse along the steps from novice to expert (Benner, 2009).

Negotiations

While registered nurses in a facility have varied educational backgrounds and represent the multiple practice specialties available to nursing, there are common practice issues/processes that need to be addressed by the nursing negotiating team. Once the common issues are addressed, the differences in practice needs must then be addressed in ongoing negotiations.

Professional goals and practice needs are appropriate topics for contract negotiations. Because personnel directors, hospital administrators, and hospital lawyers may have difficulty relating to these discussions, the nurse negotiating team has to be able to provide sufficient information to help prepare these individuals to understand the inclusion of professional goals and practice needs into the collective bargaining process and as entries into the agreed-on contract. The resolution of disagreements about professional issues necessitates there be time for a thoughtful process by those who are appropriately prepared to reach agreements through the negotiating process. Perhaps the complex issues such as recruitment, retention, staffing, and health and safety are better addressed in the more collegial setting of the nontraditional model; however, many of these issues are paramount to the creation of a safe and effective work environment for nurses, and they need to be addressed in both types of negotiations (Institute of Medicine, 2004).

The Debate Over Collective Bargaining

Collective Bargaining: Perspectives of the Traditional Approach

Is There a Place for Collective Bargaining in Nursing?

Should registered nurses use collective bargaining if they are members of a profession? Is nursing a profession or an occupation? Those in the nursing profession have debated these questions since the late 1950s, and the discussion and debate continue today. Nurses often look for assistance outside of nursing to help resolve issues, but these two questions can and should be resolved by nurses, if registered nurses are to be recognized as independent and in control of their practice.

According to the New York Department of Labor, “A registered professional nurse is a licensed health professional who has an independent, a dependent, and a collaborative role in the care of individuals of all ages, as well as families, groups, and communities. Such care may be provided to sick or well persons. The registered nurse uses the art of caring and the science of healthcare to focus on quality of life. The registered nurse accomplishes this through nursing diagnosis and treatment of a patient’s, family’s or community’s responses to health problems that include but are not limited to issues involving the medical diagnosis and treatment of disease and illness” (New York Department of Labor, 2014, para 1). Defining what each level of registered nurse education best prepares one to practice can also be an issue discussed and agreed to through the process of collective bargaining. However, it must be recognized that these definitions are specific to each institution as the practice of professional nursing is defined at these individual facilities. Perhaps, over time, the profession of nursing will reach consensus regarding practice and the level of education completed, and this will no longer have to be a negotiated item! Because of their expertise and the value of their service, members of a profession are granted a measure of autonomy in their work. This autonomy permits practitioners to make independent judgments and decisions on the basis of a theoretical framework that is learned through study and practice. Although there may still be some who do not agree with the need for baccalaureate education, required for nursing to be designated as a profession, consider the fact that the absence of this professional designation continues to prevent nurses from the control over and definitions of their practice and of reaching their potential contributions to patient care and the health care system in which they are practicing.

In each state, registered nursing continues to be categorized as an occupation by the respective labor boards, and many decisions regarding the position of nursing in an organization are based on this classification as an occupation. However, for the purposes of the discussion on traditional and nontraditional collective bargaining, the role of nursing will be addressed as that of a profession.

Registered nurses need to consider the power granted to them and to the profession when they earn their license to practice nursing. The legal authority to practice nursing is independent from any other licensed professional or regulatory organization. This power of independence includes taking the responsibility for one’s practice and for the practice of others when that practice negatively impacts patients and/or the community. This power is also an important element when entering into collective bargaining, because the independently licensed registered nurse must ensure the agreement supports this independence when addressing areas of clinical practice. Conflict arises as registered nurse employees advocate for a professional role in patient care when they are not classified as a profession by labor definitions and by the hiring facilities. The health care institutions hire registered nurses as members of an occupation who are essentially managed and led by the organization’s formal leaders who often focus on productivity and savings. However, the hiring organization may not put registered nurses in situations where the independent clinical responsibilities cannot be met.

This potential conflict is a factor leading registered nurses to consider unionization as the only way they can demonstrate control over their clinical practice, particularly if shared governance is not used at their place of practice.

Registered Nurse Participation in Collective Bargaining

If the state nurses associations were considered to be logical bargaining agents for registered nurses, why do so few nurses join these associations, and why are even fewer associations pursuing collective bargaining? “ANA, a nursing organization … reportedly represents 163,111 RNs of the almost 3 million RNs that are active in this country” (Center for Union Facts, 2016). It is important to recognize that this low membership rate is not unique to nursing but is the same for most disciplines and for society in general. However, this low membership rate may also reflect the thinking of some that the professional organization for registered nurses may not be the best organization to represent the nursing population for collective bargaining. Perhaps the conflicts that would likely arise between a professional organization and a collective bargaining organization could be avoided by not combining these two distinct processes under one umbrella.

One of the problems with association memberships is that people tend to look at these associations and organizations for “what they can do for me”—for the work I do or the benefits I can receive. In reality, we need to look at these associations for what they can do for the profession and the population being served by the members of the profession/occupation. We then realize that the profession is only as strong as its members and the contributions they make to that occupation/profession. Perhaps looking at it in this way will encourage more to join and become members. The professional association can provide the standards and ethical platforms for a professional practice that would then be used as the basis for a collective bargaining contract.

The current labor climate is very volatile across the country. Unions are trying to organize new categories of workers, with special emphasis on the growing health care sector in states that have not traditionally been active in the labor movement. Some state nursing associations stopped providing collective bargaining services because of external pressures, including challenges from competing unions, excessive resistance by employers, or state policies that make unionization difficult, such as right-to-work laws. In states with right-to-work laws, it is illegal to negotiate an agency shop requirement. Membership and dues collection can never be mandatory, even if the workers are covered by a collective bargaining agreement. The cost of negotiating and maintaining a collective bargaining agreement in these states is often more than the income received for providing these services. Philosophical differences regarding the benefits and risks of a professional association as the bargaining agent have also led registered nurses in some states to abandon or avoid union activities or to avoid joining the professional association.

There are 2.6 million employed registered nurses in the United States, but only a few hundred thousand are organized for collective bargaining, and only around 20% of RNs belong to a professional organization. Sixty-one percent of these registered nurses are employed by hospitals (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016).

How will collective professional goals be achieved if so many nurses depend on the time and finances of so few? Some believe that the profession’s efforts to address workplace concerns from both the traditional and nontraditional perspectives will result in larger membership numbers in the near future. For now, there may be too few registered nurses involved in the nursing associations to make up the needed critical mass for the kinds of changes and support that need to take place. Perhaps learning that this is the case will motivate more RNs to join their professional organization to support the work that needs to be accomplished. The implementation of the National Nurses United as the “RN Super Union” (Massachusetts Nurses Association, 2016) may supplant the state nurses associations as the primary provider of collective bargaining services for registered nurses.

Where Does Collective Bargaining Begin?

As stated in the National Labor Relations Act, registered nurses in the private sector are guaranteed legal protection if they seek to be represented by a collective bargaining agent. After a drive for such representation is under way and 30% of the employed RNs in an organization have signed cards signaling interest in representation, both the employer and the union are prohibited from engaging in any anti-labor action. Employers are prohibited from terminating the organizers for union activity, and they may not ignore the request for a vote for union representation. After the organizing campaign, a vote is taken; a majority, comprising 50% plus one of those voting, selects or rejects the collective bargaining agent.

The employer may choose to bargain in good faith on matters concerning working conditions by recognizing the bargaining agent before the vote. This approach usually occurs only if management believes a large majority of potential voters support the foundation of a union. In other cases, the employer may appeal requests for representation to the NLRB. Before and during the appeal, other unions may intervene and try to win a majority of votes for representation.

As a part of this appeal process, arguments are made before the NLRB regarding why, by whom, or how the nurses are to be represented. For example, the hospital may raise the question of unit determination. The original policy interpretation of the labor law simultaneously limited the number of individual units an employer or industry would have to recognize, yet allowed for distinct groups of employees, such as RNs, to receive separate representation. Nurses historically have been represented in all-RN bargaining units, and most bargaining units throughout the country reflect that pattern.

What Can a Union Contract Do?

Generally speaking, what can a union contract do in a hospital setting? Many believe that, today more than ever, registered nurses need a strong union such as the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA) (NYSNA, 2016). Nurse shortages and the rise of health care for profit have dramatically changed the environments in which RNs are practicing and the demands that are placed on them. Too many nurses are spending too much time on duties that can be completed by staff other than RNs. Too many nurses are enduring too much overtime and are working under conditions that are unsafe for them and their patients.

Members of the NNU believe a strong, unified workforce is the best solution to the problems facing RNs and their patients today. When RNs become members of NNU, for example, they gain the ability to negotiate enforceable contracts that spell out specific working conditions such as acceptable nurse–patient ratios, roles RNs will play in determining standards of care, circumstances under which RNs will agree to work overtime, pay scales, benefits, dependable procedures for scheduling vacations and other time off, and all other similar conditions important to nurses.

A contract can also include language related to clinical advancement, such as is measured by the use of a clinical ladder or a similar mechanism. This is one way to bring concepts that have traditionally been avoided in collective bargaining strategies into the contracts to address practice aspects of the profession. When actions such as this occur, it could be anticipated that more registered nurses will support collective bargaining.

Wages

Wages and benefits are the foundation of a contract. Wages are the remuneration one receives for providing a service and reflect the value put on the work performed. In an article on the history of nursing’s efforts to receive adequate compensation, Brider (1990) reaffirmed the need to continue efforts to improve nursing salaries. The author correctly stated that “from its beginnings, the nursing profession has grappled with its own ambivalence which is how to reconcile the ideal of selfless service with the necessity of making a living” (Brider, 1990, p. 77). The article confirmed the ambivalence of the nurses who recorded both their joy in productive careers and their disappointment with the way their work was valued. Registered nursing has certainly come a long way from the $8 to $12 monthly allowance in the early 1900s, but the challenge remains to bring nursing in line with comparable careers.

As we progress through the 21st century, it is clear periods of a shortage of nurses will occur. Like other occupations and professions, when the supply and demand favor the employee, wages are more critically evaluated. More recent shortages of registered nurses seem to be less responsive to some of the traditional solutions such as wage adjustments. This likely indicates that wages are not the only, or perhaps not even the primary, reason that individuals are not choosing registered nursing as a career or that many registered nurses are choosing to leave the field.

Another aspect of registered nurse compensation involves the challenge of addressing the negative effects of wage compression. This economic concept means that registered nurses who have been in practice for 10 and 12 years may make less money than recent graduates in their first registered nursing jobs! Unfortunately, it is not uncommon during times of shortages to see hiring or relocation bonuses to attract registered nurses into new positions. It would be preferable to see those dollars redistributed for the purposes of maintaining the base that is formed by the retention of experienced registered nurses in the facility.

Job security versus career security

It is probably not news to any student enrolled in a registered nursing program that he or she has entered a field that is facing many challenges—both from within and from outside nursing. Challenges related to the need for more registered nurses will occur primarily because of technological advancements; an increased emphasis on primary and preventative care; and the large, aging Baby Boomer population who will demand more health care services as they live longer and more active lives (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). Additionally, challenges related to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act of 2010 are to be expected, and planning for ways to address these challenges are under way.

The total number of licensed registered nurses in the United States in 2016 was approximately 3.13 million (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016). Of the 3.13 million professionally active registered nurses, 61% work in hospitals (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). The need for so many additional registered nurses coupled with the anticipated growth in the profession provides an opportunity to achieve some of the professional goals that have eluded nursing thus far, including full recognition as a profession and all that entails.

According to Juraschek, Zhang, Ranganathan, and Lin (2012), a shortage of registered nurses is projected to spread across the country over the next two decades, with the South and West most heavily impacted. The researchers noted an aging population requiring health care services, health care reform legislation, and aging RN workforce as factors contributing to the nursing shortage. These new paradigms will also challenge nurses and their representatives to modify bargaining strategies and turn attention to issues of sustaining quality in nursing care in the face of shortages, to overcome negative practices such as mandatory overtime, and to advocate for health and safety initiatives.

Seniority rights

Registered nurses who remain on staff at an organization accrue seniority that is based on the length of time employed as a registered nurse at that facility. Seniority provides specific rights, spelled out in the bargaining agreement, for those who have the highest number of years of service. These rights are derived from the idea that permanent employees should be viewed as assets to the organization and should therefore be rewarded for their service. In nurse employment contracts, there may be provisions (seniority language) that give senior nurses the right to accrue more vacation time and to be given preference when requesting time off, a change in position, or relief from shift rotation requirements. In the event of a staff layoff, the rule that states “the last hired becomes the first fired” protects senior nurses. Seniority rules may be applied to the registered nursing staff of the entire hospital or may be confined to a unit. However, transfers and promotions must reward the most senior qualified nurse in the organization.

Resolution of grievances

Methods to resolve grievances, which are sometimes explicitly spelled out in a contract, are an important element of any agreement. A grievance can arise when provisions in a contract are interpreted differently by management and an employee or employees. This difference often occurs when issues related to job security (a union priority), job performance, and discipline (a management priority) arise. Grievance mechanisms are used in an attempt to resolve the conflict with the parties involved. The employer, the employee, or the union may file a grievance. Nurses who are covered by contracts should be represented at any meeting or hearing they believe may lead to the application of disciplinary action. A co-worker, an elected nurse representative, or a member of the labor union’s staff can provide such representation.

Arbitration

If the grievance mechanism does not lead to resolution of the issue, some contracts allow referral of the issue for arbitration. A knowledgeable—but neutral—arbitrator acceptable to both parties (union and hospital) will be asked to hear the facts of the case and issue a finding. In pre-agreed, binding arbitration, the parties must accept the decision of the arbitrator. For example, some contracts require that when management elects to discharge (suspend or terminate) a nurse, the case must be brought to arbitration. Based on the arbitrator’s finding, the nurse may be reinstated, perhaps with back pay, may remain suspended, or may be terminated. If the contract states that the arbitrator’s decision is final and binding, there is no further contractual or organizational avenue for either party to pursue.

Arbitration has also been used to resolve issues involving the integrity of the bargaining unit. Arbitrators have been asked to decide whether nurses remain eligible for bargaining unit coverage when jobs are changed and new practice models are implemented.

There is strong support for the use of these three methods, but hospital management personnel often resist using them. Nurses usually fare well when contract enforcement issues are submitted to an arbitrator and facts, not power or public relations, determine the outcome.

Strikes and other labor disputes

What can nurses do in the face of a standoff during contract negotiations? The options that current RNs have are quite different from those before 1968, when nurses felt a greater sense of powerlessness. At that time, despite nurses’ threats of “sickouts,” walkouts, picketing, or mass resignations, the employer maintained an effective power base. Threats of group action attracted public attention, but nurses’ threats had little effect on employers, because nurses who were represented through the ANA had a no-strike policy. As negotiations became more difficult, it was apparent that nurses were in a weaker bargaining position because of the no-strike policy. The ANA responded to the state nursing associations, and in 1968, it reversed its 18-year-old no-strike policy. The NNU does not have a no-strike policy.

Strikes remain rare among nursing units, but as mentioned previously, when the efficacy of patient care and patient and staff safety are at risk, registered nurses may believe they have to strike. Increased strikes were seen beginning in 2000 as facilities were imposing mandatory overtime to cover the staff shortages. Many nurses are uncomfortable with the idea of striking, believing that they are abandoning their patients. It is important for nurses who contemplate striking to discuss plans for patient care with nurses who have previously conducted strikes so that they will be assured that plans to care for patients are adequate.

When an impasse is reached in hospital negotiations, national labor law requires registered nurses to issue a 10-day notice of their intent to strike. In the public’s interest, every effort must be made to prevent a strike. The NLRB mandates mediation, and a board of inquiry to examine the issue may be created before a work stoppage. The organization is supposed to use this time to reduce the patient census and to slow or halt elective admissions. In the meantime, the nurses’ strike committee will develop schedules for coverage of emergency rooms, operating rooms, and intensive care areas. This coverage is to be used only in the case of real emergencies. Planning coverage for patient care should reassure nurses troubled by the possibility of a strike. Nurses who agree to work in emergencies or at other facilities during a strike often donate their wages to funds that are set up for striking nurses.

Business and labor are both in search of more positive ways to work together to be able to avoid the possibility of a work stoppage. Strikes are not easy for either side—one side is not able to provide services, and the other side is not able to earn its usual income. In the middle, when health care is involved, is the patient who loses trust in both the organization and in the body of employees who choose to strike, requiring the patient to seek care elsewhere. The Department of Labor and the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service have sponsored national grants to undertake alternatives to traditional collective bargaining. At least two Midwestern nursing organizations have used win–win bargaining techniques and found them to be constructive methods for negotiation.

What Are the Elements of a Sound Contract?

Membership

The inclusion of union security provisions is an essential element of a sound contract (Fig. 18.2) and addresses one of the defined goals of collective bargaining (union integrity). Security provisions include measures such as enforcement of membership requirements (collection of dues and access by the union staff to the members). In a closed shop agreement, the employer agrees that they will only hire employees who are members of the union. Closed shops are generally illegal. Union shop agreements allow an employer to hire nonunion members but require the employee to join the union within a certain amount of time (usually after 30 days). In practice, though, employers are not allowed to fire employees who refuse to join the union, provided the employees pay dues and fees to the union. An agency shop agreement requires employees who do not join the union to pay dues and fees.

Retirement

The usual pension or retirement programs for registered nurses have been either the social security system or a hospital pension plan. Because many employers are eliminating defined pension plans, individual retirement accounts, which are transferable from hospital to hospital in case of job changes, are becoming increasingly popular. The method of addressing issues related to financial support at the time of retirement should be a topic of negotiations. The ANA has entered an agreement with a national company to provide a truly portable national plan, unrestricted by geographic location or employment site. Although this plan could be complicated by conflicting state laws governing pension plans, a precedent was set as long ago as 1976, when California nursing contracts mandated employer contributions to individual retirement accounts for each nurse with immediate vesting (eligibility for access to the fund) and complete portability for the participants (meaning that the nurse could take the established retirement account to another hospital and could continue to add to this account either directly or by rolling it over into the new employer’s individual retirement account).

One of registered nursing’s most attractive benefits has been a nurse’s mobility, which is the opportunity to change jobs at will. A drawback of this mobility is the loss of long-term retirement funds. With financial cutbacks in the hospital industry, retirement plans are in danger of being targeted as givebacks in negotiating rights or benefits to be traded away in lieu of another issue or benefit that may be more pressing at the time. One of the major benefits of individual retirement accounts is that they do belong to the employee, and the employee’s contributions to the plan plus the employer’s contributions to the plan can be taken with the employee when he or she leaves that employment, assuming all the defined rules of the plan are followed.

Health insurance coverage continues to be a key concern of employees and has been at the root of the majority of labor disputes in all industries in the past few years. It is not inconceivable that nurses may be asked to trade off long-term economic security (pensions) for short-term security (e.g., health benefits, wages). There is less chance this will occur if the organization has moved from the defined pension benefit. What is more likely to occur is that the employer will ask to contribute fewer dollars to health insurance premiums and/or retirement accounts and will ask employees to contribute an increased percentage of the cost of these benefits.

Other benefit issues

Other issues that have affected RNs as employees are family-leave policies, availability of daycare services, long-term disability insurance, and access to health insurance for retirees. These are the same issues that affect many workers in this country but may have a greater impact on employees such as registered nurses because of the 24-hour-a-day/7-day-a-week coverage that needs to be provided by this professional group.

An issue of special concern to RNs involves the scheduling of work hours. Although more men have joined the nursing occupation/profession, registered nursing remains a female occupation (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016b). This reality must be addressed by providing benefit packages that provide flexibility for women who assume multiple roles in today’s society. Generally, it is women who provide ongoing care to both children and parents. The nurse in the family may be called on to do this more than the spouse or the siblings. Registered nurses are asking nursing contract negotiators to secure leave policies that permit the use of sick time for family needs, that provide flexible scheduling that is flexible, and that allow part-time employment and work sharing.

An increasing number of men are entering the nursing field. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, men comprise approximately 9% of the current RN workforce. It is also noted that males who are practicing in the nursing profession earned a median annual salary of $60,700, whereas the median annual salary for a female RN was $51,100 (Census Bureau, 2013). Would this difference exist in an organization in which there was a collective bargaining agreement? Staffing issues, such as objection to an assignment, inadequate staffing, poorly prepared staff, mandatory overtime, nurse fatigue, and health hazards, are all concerns that can be addressed in a union contract; however, these are also issues of ongoing concern for all RNs, regardless of the type of bargaining situation in their respective states or organizations. These issues are discussed further in Chapter 25.

How Can Nurses Control Their Own Practice?

The essence of the professional nurse contract is control of practice. For example, registered nurse councils or professional performance committees provide the opportunity for registered nurses within the institution to meet regularly. These meetings are sanctioned by the contract. The elected registered staff nurse representatives may, for example, have specific objectives to

▪ Improve the professional practice of nurses and nursing assistants.

▪ Recommend ways and means to improve patient care.

▪ Recommend ways and means to address care issues when a critical nurse staffing shortage exists.

▪ Identify and recommend the elimination of hazards in the workplace.

▪ Identify and recommend processes that work to ensure the safety of patients.

▪ Implement peer-review.

▪ Implement shared governance.

Nurse Practice Committees

Registered nurse practice committees should have a formal relationship with nursing administration. Regularly scheduled meetings with nursing and hospital administrators can provide a forum for the discussion of professional issues in a safe atmosphere. Many potential conflicts regarding contract language can be prevented by discussion before contract talks begin or before grievances arise. Ideally, all health care professionals should also be a part of these forums, because they are an integral part of the care delivery system in a hospital and in other settings. Joint-practice language has been proposed in some contracts to facilitate these discussions.

Since the recognition of Magnet hospitals by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) began in 1994, approximately 7% of all health care organizations in the United States have achieved ANCC Magnet recognition status (ANCC, 2016; American Hospital Association, 2015). Magnet status is not a prize or an award. Rather, it is a credential of organizational recognition of nursing excellence. Approximately 20% of the organizations awarded the recognition have a collective bargaining agreement with the nurses. This helps to validate the fact that control of nursing practice by RN staff members can be successfully achieved within the context of a collective bargaining agreement when both Magnet and collective bargaining have this as a common goal.

Collective Bargaining: Perspectives of the Nontraditional Approach

Effectively addressing the concerns of workplace advocacy, higher standards of practice, and economic security are not new issues. These concerns have caused nurses in some areas of the country to organize and to use unions and collective bargaining models to address practice and economic concerns. This section is designed to provide you with information and a rationale for a different approach to the position of the traditional collective bargaining. In the end, it will be up to you and your concept of the RN’s role to grapple with this issue during your professional career.

Simultaneous Debates

Registered nursing today has acquired the majority of the generally recognized characteristics of a profession. One of these characteristics is a lengthy period of specialized education and practice preparation. The activities that are performed by professions are valued and recognized as important to society. In addition, a member of a profession has an acquired area of expertise that allows the person to make independent judgments, to act with autonomy, and to assume accountability. Nurses also have specialty organizations and are eligible to receive specialty credentialing in some defined areas of practice.

Another aspect of professional registered nursing is its strongly written ethical code. It is the obligation of every licensed RN to follow the tenets of the 2015 ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses (see Chapter 19). The Code articulates the values, goals, and responsibilities of the professional practice of nursing. The provisions of the Code that outline our duties to care for, advocate for, and be faithful to those people who entrust their health care to us are well integrated into the educational preparation of the RN. They are also widely recognized and respected by the public.

Collective Bargaining: The Debate That Continues

The debate about the appropriateness of collective bargaining continues. The combination of an explosion in knowledge and technology and an expanded population able to access health care quickly brought both public and private sector payers of health care to the inevitable quest to rein in the cost of health care. This gave birth and life to a growing collection of payment systems. There are now gatekeepers, specific practice protocols, contractual agreements between payers and providers, and provider and consumer incentives that govern the place, provider, type, and quantity of a patient’s care. These developments have affected everyday care in a growing number of settings. Nurses are challenged daily in practice environments that have evolved to business models to survive financially while continuing to provide care to a defined population of patients. Many registered nurses feel these business and financial environments are not conducive to the patient-focused or family-centered models of care delivery or to the ethical values that have been an inherent part of the professional education and practice preparation of nurses. All too often, the intense clinical education of the RN practicing in today’s health care environment has not prepared the individual to appreciate the financial and regulatory realities of a large industry. Perhaps even more disconcerting is the fact that as RNs enter the workforce, they may not see the magnitude of their potential for leadership and problem solving within an environment that continues to evolve so quickly while the environment continues to work hard to hold on to the traditional hierarchy of medicine and health care administration.

The history of the position of registered nursing during the first half of the 20th century may, in part, explain our slow journey toward leadership and control of nursing practice. In the last half of the 20th century, some registered nurses organized and relied on collective bargaining units to speak for them. Time and energy have been spent debating who can or should best represent professional nurses in the workplace. The transition of collective bargaining from the ANA, who established the foundation for acceptance of collective bargaining by registered nurses, to the growing NNU, may signal that the journey toward gaining control of nursing practice will move more quickly. These two strong organizations could take steps to gain acceptance of the concept that control of nursing practice by registered nurses is not congruent with “holding on to the traditional hierarchy of medicine and administration.”

Traditional Collective Bargaining: Its Risks and Benefits

The goal of the traditional collective bargaining model is to win something that is controlled by another. There is an “us versus them” approach. The weapon is the power of numbers. Although a desired contract is achieved, long-lasting adversarial relationships may develop between the nurses and the employer (Budd et al., 2004) (see Critical Thinking Box 18.2).

Traditional collective bargaining held promise and assisted the professional nurse’s evolution toward economic stability. These were important gains. However, the full power and potency of nursing as an industry leader has not emerged through traditional collective bargaining efforts. This may explain the dissatisfaction of the nurses with traditional collective bargaining or may also be an indication that the other basic debates within the body of RNs need to be resolved before nurses take the place in the industry they feel is appropriate for them.

Can nursing effectively step away from the adversarial process of traditional collective bargaining into an effective leadership role? IBB and/or processes such as shared governance may offer nurses a nonadversarial approach, but it will require nursing leaders to demonstrate an understanding of interests and outcomes that are important both to the nursing occupation/profession and to other members of the health care industry (Budd et al., 2004). As discussed earlier in this chapter, IBB is a nontraditional style of bargaining that attempts to solve problems and resolve differences between the workforce and the employer—or the nurse and the hospital. Although this style of bargaining and mediation will not always eliminate the need for the more traditional and adversarial collective bargaining, this nonadversarial approach of negotiation may be closer to the basic beliefs underlying professional nursing as well as the nursing code of ethics.

In considering nontraditional approaches, it is important to recognize state nurse associations that have made significant contributions to their local membership by offering IBB services to that membership. This has also resulted in contributions to the advancement of nontraditional, nonadversarial bargaining for the promotion of workplace advocacy on a national level (Box 18.2). Do these commitments sound familiar?

Future Trends

The public should be concerned about an inadequate supply of nurses. Based on that concern, along with the multiple other issues that are impacting the provision of health care now and in the future, there is increased interest by the press and policymakers to be sure registered nurses are prepared in adequate numbers and that their working environment supports quality nursing care. This attention is helping nurses achieve improvements in overall compensation and working conditions and may also lead to support for the preparation of sufficient numbers of registered nurse faculty and methods of financial support for the education of RNs.

The nursing community should take a step back and try to identify those factors that appear to keep registered nursing from becoming a profession of choice, which should result in eliminating the continuous cycle of shortage/staff reduction/shortage. One of the classic issues is that nursing is still not considered a profession according to most definitions of a profession or according to the labor bureaus that classify employee groups. Until nurses accept the fact that we cannot just say we are a profession without meeting the minimum criteria for this designation, we will continue to be classified as an occupation only.

The movement to gain recognition as a profession is the next issue to be addressed in the next few years. Discussions regarding this requirement are found in Chapter 9. Another issue that must be addressed by organized nursing is the silence of nursing, as defined and discussed by Buresh and Gordon (2006). These authors completed extensive research to determine why nurses were rarely seen or heard in the various forms of media. They discovered that, for the most part, the media cannot find registered nurses who are willing to talk, to be interviewed, or to write editorials stating opinions or positions. More important, when nurses were available to talk to the media, they “too often unintentionally project an incorrect picture of nursing by using a ‘virtue’ rather than a ‘knowledge’ script” (Buresh & Gordon, 2006, p. 4). They also noted that nurses tend to downplay or devalue basic registered nursing bedside care, the heart of what we do, while focusing on the greater status of the advanced practitioner.

As with many things in life, there is a tendency to look outside of the problem to define a cause for the problem and to look to others to find a solution. Nursing, as the largest group of health care providers and as the only group of providers entrusted to implement the majority of the medical plan of care, needs to look within to find how to communicate most effectively the vital role we take in the provision of health care.

Nurses throughout the country have felt firsthand the effects of cost containment. Those effects have often been detrimental to the quality of care that RNs are charged to provide. From a professional practice perspective, mandatory overtime and short staffing are some of the factors contributing to the preponderance of medical errors documented in the Institute of Medicine report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (Institute of Medicine, 2000). The ANA was the initial voice in recognizing these as potential contributing factors and has led the way in encouraging research agendas that further quantify the number of work hours needed to provide safe care and further define how patient safety can be ensured. As with other major issues affecting the practice of RNs, the ANA and state nursing associations are in the lead in federal and state legislative efforts to address overtime and staffing in the context of safe patient care.

As concerned nurses, we need to remain vigilant about our need to meet the basic obligation of licensure, which is to provide safe care to all patients. This issue of adequate access to health care services is one that will probably be with us for the rest of our professional careers. It is believed by many that one way to improve access to services is to deliver them in environments and by providers that have not traditionally been a part of our health care system. Each of these venues provides significant opportunities for RNs, because the essence of our work is the prevention of disease and the adaptability to chronic disease processes that will enable our patients to remain as active as possible in their own environment.

Conclusion

Nursing has a unique contract with society to promote effective health care and, as a natural outcome, promote the health and welfare of the nurse and the occupation/profession of nursing. The multipurpose nature of the professional nursing association will continue to work to preserve the future of nursing. This chapter cannot stand alone, nor can the nurses in the workplace stand alone if they are to offset the forces that negate the contributions of nurses. Political action and lobbying, research, and education are necessary to further the cause of nursing and to meet the health care needs of the public we serve. As nurses work to transform aspects of the health system and to improve access to care, they will continue to depend on collective action and a collective voice through the structures and functions initially established within the ANA to advocate for optimal working conditions and standards of practice. There are now multiple opportunities to continue to advance the collective voice of nursing to ensure that the profession of nursing will be available to provide the quality care and services to all those who are in need of this care and service (see the relevant websites and online resources below). Welcome to nursing! Join us in our efforts to unify our skills, knowledge, and voices as we ensure our vision is being met.