Chapter 69 Cold Injuries

Clinical Manifestations

Hypothermia

Hypothermia may occur in winter sports when injury, equipment failure, or exhaustion decreases the level of exertion, particularly if sufficient attention is not paid to wind chill. Immersion in frozen bodies of water and wet wind chill rapidly produce hypothermia. As the core temperature of the body falls, insidious onset of extreme lethargy, fatigue, incoordination, and apathy occurs, followed by mental confusion, clumsiness, irritability, hallucinations, and finally, bradycardia. A number of medical conditions, such as cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, hypoglycemia, sepsis, β-blocking agent overdose, and substance abuse, may need to be considered in a differential diagnosis. The decrease in rectal temperature to <34°C (93°F) is the most helpful diagnostic feature. Hypothermia associated with drowning is discussed in Chapter 67.

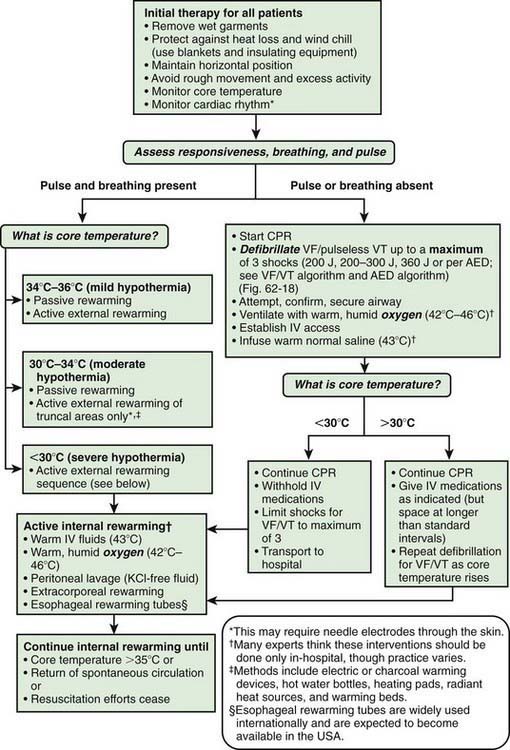

Treatment at the scene aims at prevention of further heat loss and early transport to adequate shelter. Dry clothing should be provided as soon as practical, and transport should be undertaken if the victim has a pulse. If no pulse is detected at the initial review, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is indicated (Chapter 62; Fig. 69-1). During transfer, jarring and sudden motion should be avoided because these occurrences may cause ventricular arrhythmia. It is often difficult to attain a normal sinus rhythm during hypothermia.

Cold-Induced Fat Necrosis (Panniculitis)

A common, usually benign injury, cold-induced fat necrosis occurs upon exposure to cold air, snow, or ice and manifests in exposed (or, less often, covered) surfaces as red (or, less often, purple to blue) macular, papular, or nodular lesions. Treatment is with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. The lesions may last 10 days to 3 wk (Chapter 652) but may persist for longer. There is a possibility of severe coagulopathy associated with poor outcome in some of the severe cold injuries, thus meriting anticoagulation therapy.

Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546-551.

Hallam MJ, Cubison T, Dheansa B, Imray C. Managing frostbite. BMJ. 2010;341:1151-1156.

Shephard RJ. Metabolic adaptations to exercise in the cold: an update. Sports Med. 1993;16:266-289.

Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350-1354.

Walpoth BH, Walpoth-Aslan BN, Mattle HP, et al. Outcome of survivors of accidental deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest treated with extracorporeal blood warming. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1500-1505.