Cold and cough agents

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Define key terms that pertain to cold and cough agents

2. Differentiate between the common cold and the flu

3. Differentiate between the specific types of cold and cough agents

4. Discuss the mode of action for each specific cold and cough agent

Bewildering and in some cases irrational numbers of compounds, both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC), are available for treating symptoms of the common cold. The term “common cold” is used to describe nonbacterial upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), usually characterized by a mild general malaise and a runny, stuffy nose. Other symptoms include sneezing, possible sore throat, cough, and possibly some chest discomfort. Allergic rhinitis and serious illnesses such as influenza, acute bronchitis, and infections of the lower respiratory tract are not included in this discussion. Influenza, or the “flu,” caused by the influenza virus is associated with symptoms of fever, headache, general muscle ache, and extreme fatigue or weakness. Onset of symptoms is usually rapid. The fever and systemic symptoms of influenza are contrasted with symptoms of the common cold in Table 15-1.

TABLE 15-1

Differences in Symptoms between the Common Cold and Influenza

| SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | COLD | INFLUENZA |

| Fever | Rare | Typical, high |

| Chills | None | Typical |

| Cough | Present, hacking | Nonproductive, may be severe |

| Headache | Rare | Prominent |

| Fatigue | Mild | Early and severe |

| Myalgia | None or slight | Usual, may be severe |

| Nasal congestion | Common | Occasional |

| Sneezing | Common | Occasional |

| Sore throat | Common | Occasional |

• Sympathomimetics: For decongestion

• Antihistamines: To reduce (dry) secretions

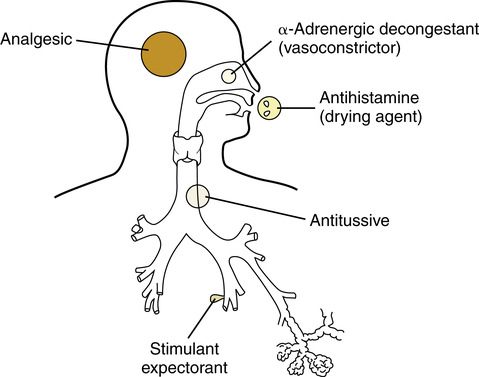

The above-listed four classes of cold medications target the primary symptoms caused by the cold virus in the respiratory tract; this is illustrated conceptually in Figure 15-1. Each class is discussed briefly, with representative agents listed. In addition to these four types of ingredients, an analgesic such as acetaminophen may be included, as in Sinutab, which consists of 30 mg of pseudoephedrine (decongestant) and 325 mg of acetaminophen (analgesic).

Sympathomimetic (adrenergic) decongestants

Sympathomimetic (adrenergic) agents are discussed as bronchodilators in Chapter 6, and the general effects of sympathetic stimulation are outlined in Chapter 5. In cold remedies, sympathomimetics are intended for a decongestant effect, which is based on their α-stimulating property and resulting vasoconstriction.

Sympathomimetics such as pseudoephedrine are found under brand names such as Sudafed and Dimetap and can be taken orally. As a result of changes in the U.S. Patriot Act, single agents or combination drugs using pseudoephedrine are placed behind the counter in pharmacies and regulated sales are documented because the drug has been overpurchased for use in the illegal production of methamphetamines. Manufacturers have turned to phenylephrine as a substitute; however, the 10-mg dose that has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has little effect on nasal decongestion when used orally because of the drug’s high first-pass effect. In a meta-analysis by Hatton and associates,1 it was found that 10 mg of phenylephrine was no more effective than placebo. Oxymethazoline, a sympathomimetic with brand names such as Afrin and Vicks Sinex, can be used topically for the nasal mucosa. Topical applications generally require lower dosages than oral use. Problems can occur with either route of administration. Table 15-2 lists sympathomimetic agents used as nasal decongestants in cold remedies.

TABLE 15-2

Examples of Adrenergic Agents Used as Nasal Decongestants

| DRUG | ROUTE |

| Phenylephrine (Sudafed PE) | Topical, oral |

| Pseudoephedrine HCl (Sudafed, various) | Oral |

| Pseudoephedrine sulfate (Afrinol) | Oral |

| Xylometazoline (Otrivin) | Topical |

| Naphazoline (Privine) | Topical |

| Tetrahydrozoline (Tyzine) | Topical |

| Oxymetazoline (Afrin) | Topical |

Antihistamine agents

Histamine occurs naturally in the body and is contained in tissue mast cells and blood basophils. The role of the mast cell in releasing histamine with allergic asthma is discussed in Chapters 11 and 12.

Histamine receptors

1. H1 receptors: Located on nerve endings and smooth muscle and glandular cells. H1 receptors are involved in inflammation and allergic reactions, producing wheal and flare reactions in the skin, bronchoconstriction and mucus secretion, nasal congestion and irritation, and hypotension in anaphylaxis.2

2. H2 receptors: Located in the gastric region. H2 receptors regulate gastric acid secretion and feedback control of histamine release.2

3. H3 receptors: Located primarily in the central nervous system (CNS). H3 receptors may be autoreceptors for cholinergic neurotransmission in the airway at the autonomic ganglia, involved in CNS functioning and feedback control of histamine synthesis and release.2,3

The typical antihistamine found in cold medications is an H1-receptor antagonist. Examples of these are pyrilamine and chlorpheniramine. H1-receptor antagonists block the bronchopulmonary and vascular actions of histamine, to prevent rhinitis and urticaria.4 H2-receptor antagonists are used to block gastric acid secretion when treating ulcers. Examples of H2-receptor antagonists are cimetidine (Tagamet) or ranitidine (Zantac).

Antihistamine agents

All of the antihistamines discussed in this chapter are H1-receptor antagonists. These antihistamine agents are classified further into the major groups listed in Table 15-3. The first five groups of antihistamines listed in Table 15-3 all are first-generation agents and can be found in cold preparations. Some of the brand names given may be familiar from OTC preparations readily available in drugstores. Others are found in combination products; these are discussed and listed subsequently. Second-generation antihistamines, which are longer acting and nonsedating, are also listed in Table 15-3.

TABLE 15-3

Major Groups of Antihistamines with Representative Agents by Nonproprietary and Brand Names

| GROUP | DRUG |

| First Generation (Nonselective) | |

| Ethanolamine derivatives | Diphenhydramine HCl (Benadryl) |

| Clemastine (Tavist) | |

| Carbinoxamine | |

| Piperazine | Hydroxyzine (Vistaril) |

| Piperidine derivatives | Cyproheptadine |

| Phenothiazine derivatives | Promethazine HCl |

| Alkylamine derivatives | Chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton) |

| Brompheniramine | |

| Dexchlorpheniramine maleate | |

| Second Generation (Peripherally Selective) | |

| Nonsedating, Long-Acting | |

| Phthalazinone | Azelastine (Astelin, Astepro) |

| Piperidines | Loratadine (Claritin) |

| Fexofenadine (Allegra) | |

| Desloratadine (Clarinex) | |

| Piperazine | Cetirizine (Zyrtec) |

| Levocetirizine (Xyzal) | |

| Olopatadine (Patanase) |

Effects of antihistamines

The sedative effect of antihistamines is thought to be caused by penetration of the agents into the brain, where inhibition of histamine N-methyltransferase and blockage of central histaminergic receptors occurs. There is also antagonism of other CNS receptors, such as serotonin and acetylcholine.2 The effect of drowsiness with first-generation (older) antihistamines can be a major hazard if alertness is required, such as in operating heavy machinery (e.g., a car) or monitoring a patient. This effect can be so pronounced that diphenhydramine HCl is added to acetaminophen in Tylenol PM, and the compound is described as a nonprescription sleep aid.

Finally, the anticholinergic effect produces considerable upper airway drying, just as would occur with an antimuscarinic agent such as atropine sulfate. In addition, effects seen with cholinergic blockade may occur, including CNS effects of stimulation, anxiety, and nervousness and peripheral effects of dilated pupils, blurred vision, urinary retention, and constipation.3 These effects are less likely in occasional use with a cold, but they may be significant with greater use (and dose) for allergic rhinitis or other conditions (e.g., urticaria).

The duration of action of older antihistamines is generally 4 to 6 hours. However, newer, second-generation agents, often termed “nonsedating,” are effective for 12 hours or more, depending on dose, and lack the sedating and anticholinergic effects. Examples of these newer agents are fexofenadine (Allegra) and cetirizine (Zyrtec) (see Table 15-3). Second-generation agents have little affinity for muscarinic cholinergic receptors and therefore do not cause dry mouth or gastrointestinal side effects. They also lack antiserotonin activity and do not cause appetite stimulation and weight gain, although astemizole and ketotifen may differ in this.3 These newer drugs may inhibit mediator release from allergic inflammatory cells, in addition to blocking the histamine receptor. Allergic symptoms of sneezing and rhinorrhea are equally well controlled with first-generation and second-generation H1 antagonists.3

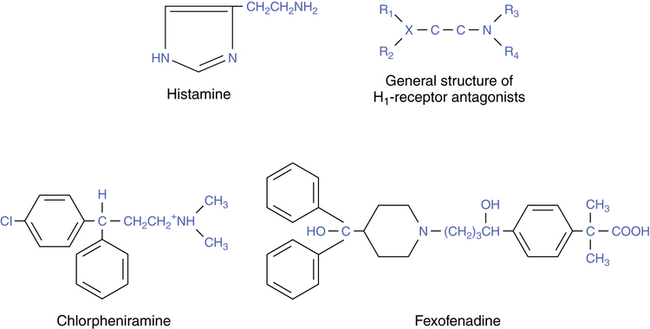

Structure-activity relationships

H1-receptor antagonists were first discovered in 1937.4 The chemical structure of histamine, the general structure of H1-receptor antagonists, and two examples of H1-receptor antagonists are shown in Figure 15-2. Chlorpheniramine is an antihistamine found in many cold remedies; it represents one of the older, classic H1-receptor antagonists. Fexofenadine is a newer, nonsedating H1-receptor antagonist.

The resemblance between histamine and the general formula for the H1-blocking agents can be seen in the structures shown. In older agents, exemplified by chlorpheniramine, R1 and R2 attachments are usually a ring structure connected to an ethylamine (C–C–N) group. The presence of the ring structures and other substitutions on the structure makes older antihistamines lipophilic. As a result, classic first-generation antihistamines readily penetrate into the CNS and produce the effect of sedation and drowsiness previously discussed. Newer, nonsedating agents, such as terfenadine, do not readily cross the blood-brain barrier and therefore do not block central H1 receptors.4

Use with colds

Regardless of the exact effect, the drying of runny nasal secretions is welcomed by individuals with a cold, and the drying of secretions coupled with drowsiness can be useful to produce needed rest and sleep at night. Secretions, however, are a defense mechanism with an upper airway viral infection. Antihistamines may cause harm as a result of suppressed secretion clearance and impacted secretions with sinus blockage.4 Adequate hydration with a cold is always helpful, with or without use of antihistamines.

An alternative to antihistamines for rhinorrhea in a cold is the anticholinergic nasal spray ipratropium bromide (Atrovent), which is discussed in Chapter 7. Ipratropium has been shown to be effective in reducing nasal discharge in viral infectious rhinitis (colds) and allergic and nonallergic rhinitis.5 There is no evidence of rebound congestion, mucosal irritation, or significant systemic effects. Ipratropium can be effective for 4 to 8 hours. An anticholinergic agent applied topically offers an attractive alternative to vasoconstricting decongestants and antihistamine H1 antagonists.

Treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis

Second-generation H1-receptor antagonists are more useful in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis and other disorders requiring antihistamine treatment than in the treatment of colds. They are also better tolerated in treating allergic rhinitis than the first-generation agents because side effects of drowsiness are minimal, and duration of action is longer. Agents such as astemizole, loratadine, fexofenadine, and cetirizine are indicated for use in seasonal allergic rhinitis and chronic urticaria. They are intended to relieve symptoms of sneezing; rhinorrhea; itchy nose, palate, and throat; itchy, watery eyes; and pruritus. Table 15-4 lists categories and examples of agents used in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis.6 Other uses of antihistamines include the treatment of symptoms seen with motion sickness and control of nausea.

TABLE 15-4

Categories of Agents Used in Treating Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis

| CATEGORY | EXAMPLE |

| H1-receptor antagonists | Cetirizine |

| Corticosteroids | Budesonide, ciclesonide |

| Mediator antagonist | Cromolyn sodium |

| Anticholinergics | Ipratropium bromide |

| Vasoconstrictors | Pseudoephedrine |

| Specific immunotherapy | Standardized extracts |

Expectorants

Expectorants are defined as agents that facilitate removal of mucus from the lower respiratory tract. A distinction is made in Chapter 9 between the following types of expectorants:

• Mucolytic expectorants: Agents that facilitate removal of mucus by a lysing, or mucolytic, action (example: dornase alfa).

• Stimulant expectorants: Agents that increase the production and presumably the clearance of mucus secretions in the respiratory tract (example: guaifenesin).

Efficacy and use

• Difficulty in assessing the effectiveness of expectorants and, in particular, lack of objective criteria to show effectiveness.

• In conjunction with the first point, who would benefit from the use of expectorants? In particular, should expectorants be included in the treatment of cold symptoms, if a cold involves the upper respiratory tract?

Use in chronic bronchitis

Petty7 reported the results of a national study evaluating use of the expectorant iodinated glycerol (Organidin). Patients had chronic bronchitis, which is quite different from a common cold. The study concluded that in chronic obstructive bronchitis, iodinated glycerol was safe and effective. Its use improved cough symptoms, chest discomfort, ease in bringing up sputum, and sense of well-being. The duration of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis was decreased. It is reasonable that in bronchitis, symptoms and airflow improve and further infection is reduced if mucus clearance can be improved. However, Rubin and associates8 found no change in lung function or sputum in patients with chronic bronchitis.

Irwin and colleagues9 published evidence-based guidelines in the diagnosis and management of cough. The guidelines cover acute and chronic cough and specific diseases such as chronic bronchitis and cystic fibrosis. The specific guidelines can be accessed at http://www.chestjournal.org/cgi/content/full/129/1_suppl/1S.

Mode of action

• Vagal gastric reflex stimulation

• Absorption into respiratory glands to increase mucus production directly

Guaifenesin, also known as glycerol guaiacolate, is classified as a category I agent, which is safe and effective.10 Ziment11 reviewed the mechanisms of action with iodides, such as iodinated glycerol. Other agents, such as terpin hydrate, sodium citrate, ammonium chloride, and menthols, have no demonstrated efficacy.10

Expectorant agents

Table 15-5 lists available expectorant agents. Major agents or groups of agents are briefly characterized.

TABLE 15-5

| DRUG | REPRESENTATIVE BRAND |

| Guaifenesin (glycerol guaiacolate) | Robitussin, Mucinex |

| Iodinated glycerol | Iophen, Par Glycerol, R-Gen |

| Potassium iodide | SSKI, Pima |

Iodine products

Potassium iodide is a very old agent that has been used as an expectorant in asthma and chronic bronchitis.12 It has a direct mucolytic effect in sufficient concentrations. It also has an indirect effect on mucus viscosity by stimulating submucosal glands to produce new, lower viscosity secretions.

The exact mechanism of action with iodine products is unclear. Iodide appears to distribute to mucous glands, where it is secreted along with increased mucus. Iodide also stimulates the gastropulmonary reflex, has a mucolytic effect, and can stimulate ciliary activity.11 Iodides are associated with hypersensitivity reactions in some individuals, and a case of pulmonary edema has been reported with its use.13

Topical agents

Some research has shown that so-called bland aerosols of saline do increase sputum volume, possibly through reflex irritation of the bronchi and with increased secretion clearance as a result of coughing.14 A particulate suspension may have the potential to function as an irritant to the upper airways.

Parasympathomimetics (cholinergic agents)

Using parasympathomimetic agents stimulates mucous gland secretion, but the effect on other muscarinic receptors is too diffuse for practical use as an expectorant. For this reason, a drug such as pilocarpine is not used as an expectorant. Likewise, stimulation of the medulla can increase respiratory tract secretions, but stimulation of the CNS is hazardous (see discussion of CNS stimulants in Chapter 20).

Cough suppressants (antitussives)

A fourth category of drugs used with colds and cold symptoms is cough suppressants. Coughing is a defense mechanism to protect the upper airway from irritants such as dust particles or aerosols, liquids, and other foreign objects. This mechanism is a reflex, coordinated by a postulated cough center in the medulla. Detailed guidelines for cough management are provided by Irwin and associates.9

Agents and mode of action

Cough suppressants act by depressing the cough center in the medulla. Narcotics (see Chapter 20) exert powerful depressant effects on the medullary centers, including the carbon dioxide chemoreceptors, and are often used for this purpose. Common agents are codeine or hydrocodone. A commonly used nonnarcotic is dextromethorphan.

Benzonatate (Tessalon), a nonnarcotic, is chemically related to the local anesthetic tetracaine and anesthetizes stretch receptors in the lungs and pleura; this inhibits the cough reflex at its source. There is no inhibitory effect on the CNS. The effect begins in 15 to 20 minutes and lasts 3 to 8 hours.15 The antihistamine diphenhydramine (Benadryl), available as a syrup, in liquid form, and in combination with other products, may be an effective cough suppressant. Diphenhydramine is becoming more common in products because of increased abuse of dextromethorphan. It should be noted that individuals taking any agent with diphenhydramine should be warned of the effect of drowsiness.

Some cough suppressants, or antitussives, contain codeine. In a dose less than 15 mg, codeine does not produce analgesia in an adult. In the 10- to 20-mg range, there is an antitussive action. At doses greater than 30 mg, codeine produces analgesia. Hydrocodone produces an antitussive effect with a dose of approximately 5 mg. Box 15-1 lists common antitussive agents, many of which are used in cold compounds. Both dextromethorphan and codeine are available in OTC preparations. These two agents are considered to be preferred cough suppressants based on safety and efficacy. The need for a prescription antitussive is unusual, especially in a cold, with the availability of OTC preparations.

Use of cough suppressants

Several principles apply to the use of antitussives, as follows:

• They are helpful and indicated to suppress dry, hacking, nonproductive irritating coughs, especially if the coughing causes sleep loss. A constant nonproductive cough can cause irritation of the trachea, leading to more coughing.

• The cough reflex should not be suppressed in the presence of copious bronchial secretions that need to be cleared. This includes situations of cystic fibrosis and other chronic obstructive lung diseases such as chronic bronchitis. Excess mucus secretions from the lower respiratory tract are not present in an uncomplicated cold (see the definition of a common cold at the beginning of the chapter) and indicate the need for further evaluation and possible treatment with an antibiotic.

• The combination of an expectorant and an antitussive in a cold medication is questionable. This combination suppresses the clearance mechanism, while stimulating secretions to be cleared. Use of a single-entity cough preparation, such as Benylin DM (10 mg dextromethorphan per 5 mL) or Robitussin Pediatric (7.5 mg of dextromethorphan per 5 mL), to treat a dry, irritating cough is recommended.

Cold compounds

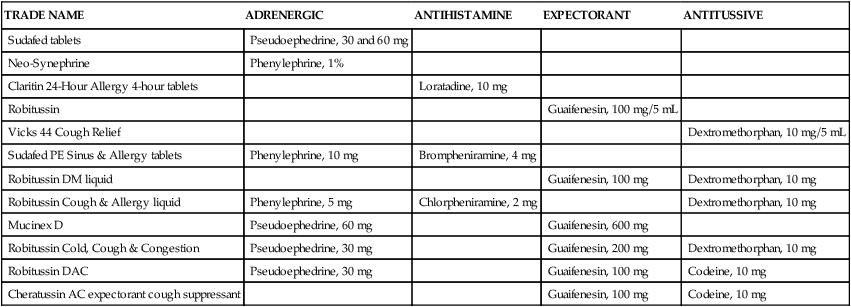

Table 15-6 lists selected cold remedies, with the classes of agents included in the compounds. Table 15-6 includes single-ingredient products, such as Sudafed, and examples of compounds with multiple drug classes, such as Sudafed PE Sinus and Allergy. Some preparations in elixir form use significant amounts of alcohol as a solvent. NyQuil Multi-Symptom Cold/Flu Relief liquid contains 25% alcohol. Another confusing aspect of cold remedies is the variation in ingredients, all under the same basic brand name with suffixed initials to indicate substituted or deleted ingredients. For example, Robitussin, Robitussin Cough & Allergy liquid, Robitussin Cold, Cough & Congestion, and Robitussin DAC all vary in ingredients (see Table 15-6). Because these compounds change fairly rapidly, no list remains current in terms of what is on the market. The basic principle of using the typical four classes of combination compounds remains, however, and new compounds can be evaluated for particular uses by considering the effects of these four classes of agents.

TABLE 15-6

Categories of Ingredients Found in Selected Cold Multicompound Medications

| TRADE NAME | ADRENERGIC | ANTIHISTAMINE | EXPECTORANT | ANTITUSSIVE |

| Sudafed tablets | Pseudoephedrine, 30 and 60 mg | |||

| Neo-Synephrine | Phenylephrine, 1% | |||

| Claritin 24-Hour Allergy 4-hour tablets | Loratadine, 10 mg | |||

| Robitussin | Guaifenesin, 100 mg/5 mL | |||

| Vicks 44 Cough Relief | Dextromethorphan, 10 mg/5 mL | |||

| Sudafed PE Sinus & Allergy tablets | Phenylephrine, 10 mg | Brompheniramine, 4 mg | ||

| Robitussin DM liquid | Guaifenesin, 100 mg | Dextromethorphan, 10 mg | ||

| Robitussin Cough & Allergy liquid | Phenylephrine, 5 mg | Chlorpheniramine, 2 mg | Dextromethorphan, 10 mg | |

| Mucinex D | Pseudoephedrine, 60 mg | Guaifenesin, 600 mg | ||

| Robitussin Cold, Cough & Congestion | Pseudoephedrine, 30 mg | Guaifenesin, 200 mg | Dextromethorphan, 10 mg | |

| Robitussin DAC | Pseudoephedrine, 30 mg | Guaifenesin, 100 mg | Codeine, 10 mg | |

| Cheratussin AC expectorant cough suppressant | Guaifenesin, 100 mg | Codeine, 10 mg |

Treating a cold

• Sympathomimetics: Tremor, tachycardia, and increased blood pressure can be seen, especially when these agents are used orally. Rebound congestion can occur if used for longer than a day.

• Antihistamines: These agents can cause drowsiness and impaired responses. Drying of secretions, whether caused by antimuscarinic or antihistamine action, may suppress a needed defense reaction of the airways. Nocturnal use is indicated more than around-the-clock use.

• Expectorants: Many of these agents have questionable efficacy in a cold. The best expectorant, especially with colds, is plain water and juices, avoiding caffeinated beverages such as tea or colas and beer or other alcoholic mixtures.

• Antitussives: These agents are useful in the presence of an irritating, persistent, nonproductive cough. Productive coughs should not be suppressed, and the logic of an expectorant-antitussive combination is questionable.