Chapter 39 Cochleosacculotomy

PHYSIOLOGIC, ANATOMIC, AND PATHOLOGIC RATIONALE

Meniere’s disease is characterized pathologically by progressive endolymphatic hydrops that is probably related to a disturbance in endolymphatic sac function. This condition must be differentiated from nonprogressive endolymphatic hydrops, in which the hydrops is the result of a single traumatic or inflammatory insult to the labyrinth, causing a permanent but not progressive endolymphatic hydrops.1

The symptoms of progressive endolymphatic hydrops can be correlated with two principal types of pathologic change: (1) distentions and ruptures of the endolymphatic system,2,3 and (2) alterations in the cytoarchitecture of the auditory and vestibular sense organs, sometimes accompanied by atrophic changes. Coincident with rupture, there is sudden contamination of the perilymphatic fluid with neurotoxic endolymph (140 mEq/L of potassium) that causes paralysis of the sensory and neural structures and is expressed clinically as episodic vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, or both. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAOHNS)4 recommended that these episodes be designated the “definitive” symptoms of Meniere’s disease.

Internal shunt procedures include the sacculotomy of Fick,5,6 the tack operation of Cody,7,8 the otic-perotic shunt of Pulec and House,9 and the cochleosacculotomy.10 In the sacculotomy and tack procedures, picks are introduced through the footplate of the stapes to puncture the saccule with the hope of producing a permanent fistula in the saccular wall by which excessive endolymph can drain into the perilymphatic space. This approach fails to consider, however, the histopathologic observation that in Meniere’s disease, the distended saccule often fills the vestibule; its distended wall is adherent to the footplate and could not be fistulized into the perilymphatic space by these maneuvers.11 The otic-perotic shunt, as conceived by House and Pulec, involves the placement of a platinum tube through the basilar membrane to connect the scala media and scala tympani; however, the procedure is not surgically feasible because of the small size of the cochlear duct.

PATIENT SELECTION

Some otolaryngologists believe that surgery is never indicated for the relief of symptoms of Meniere’s disease because in the normal course of the disease, the vertigo eventually subsides. This approach has merit if the patient is not unduly handicapped. In many cases, however, the dysequilibrium erodes occupational efficiency and recreational and family lifestyle to the extent that invasive therapy is justified. This approach applies to patients having frequent and severe vertiginous episodes unrelieved by medication and patients having falling attacks (Tumarkin’s otolithic catastrophe).19

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

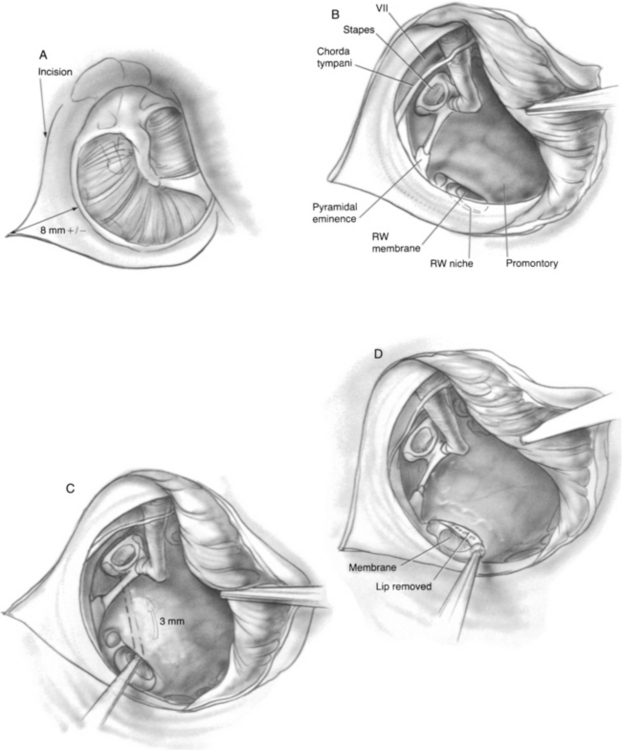

Incisions are made, and a triangular skin flap is elevated to the tympanic annulus (Fig. 39-1A). Bleeding must be meticulously controlled at all times. The tympanomeatal flap is elevated by lifting the tympanic annulus from its sulcus and folding the flap into the anterior tympanomeatal angle of the ear canal (Fig. 39-1B). The chorda tympani nerve and the ossicles are not disturbed. The ear speculum is locked into a position that exposes the round window niche and posterior aspect of the hypotympanum. In rare cases, the round window niche is partly hidden behind the posteroinferior part of the bony tympanic annulus, in which case a small burr is used to remove sufficient bony annulus to allow access to the round window niche.

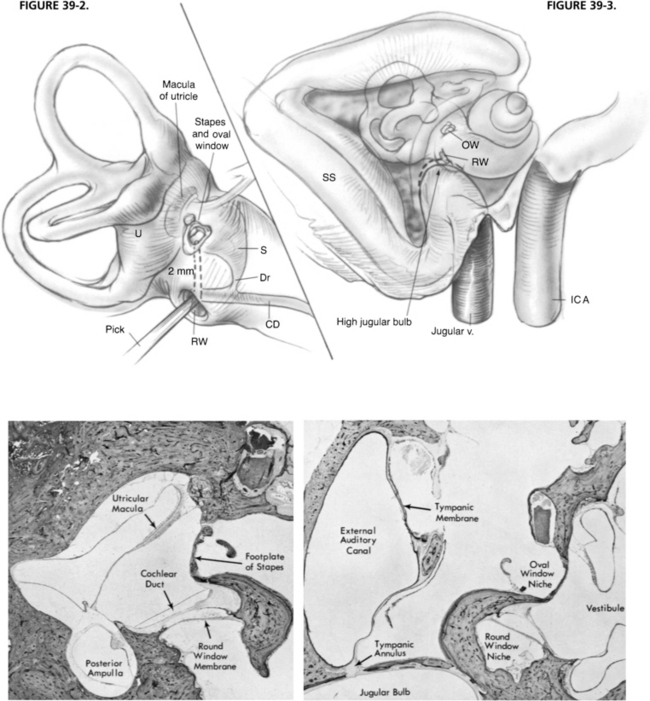

Usually, the round window niche accommodates a 3 mm right angled pick without removal of bone. The pick is advanced through the round window membrane, which may or may not be visible. The pick is guided in the direction of the oval window while hugging the lateral wall of the inner ear to ensure that the cochlear duct is traversed (Fig. 39-1C). When the pick has been introduced to its full 3 mm length, the end of the pick is located beneath the footplate of the stapes. Occasionally, the subiculum, which is a ridge of bone lying in the boundary between the round window niche and sinus tympani, interferes with introduction of the pick. It can readily be shaved down with a 2 mm burr. Occasionally, the overhanging bony lip of the round window niche must be removed to accommodate the pick (Fig. 39-1D). In this case, a 2 mm (rather than a 3 mm) pick is used to avoid excessively deep penetration into the vestibule and possible injury to the utricular macula (Fig. 39-2). Rarely, a high jugular bulb blocks access to the round window niche, in which case it may be necessary to abort the operation (Fig. 39-3).

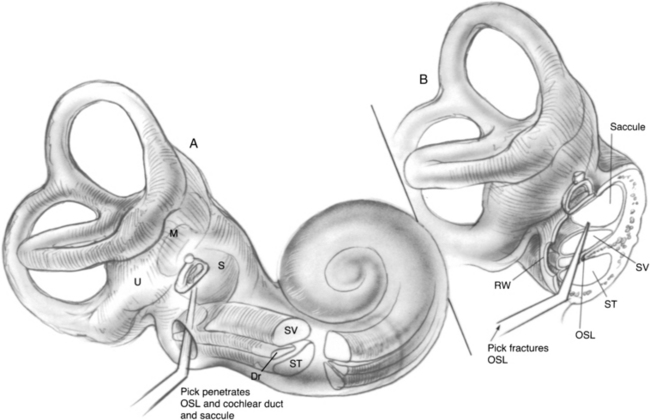

Occasionally, a slight loss of resistance is felt as the pick passes through the cochlear partition and causes the planned fracture-disruption of the osseous spiral lamina and cochlear duct (Fig. 39-4). Usually, patients experience no sensation as the pick is advanced, but a few have noted momentary vertigo, and several have reported hearing a “click.” The maneuver does not produce vertigo, presumably because the vestibular sense organs are not mechanically disturbed, and the endolymph from the fistulized area drains into the scala tympani rather than into the perilymphatic space of the vestibule. The pick is withdrawn, and the perforation in the round window membrane is sealed by a tissue graft of perichondrium or adipose tissue. The operation is terminated by returning the tympanomeatal flap to its original position. Strips of silk cloth are laid over the incisions, and a round synthetic rubber sponge of appropriate size is placed in the canal to maintain slight pressure on the skin flap. Cotton is placed in the ear canal. A few patients note slight unsteadiness for 1 or 2 days; however, all feel well enough to be discharged from the hospital the next day. The packing is removed 1 week later, at which time the tympanic membrane and canal wall skin should be well healed.

RESULTS

The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary experience currently consists of 142 cochleosacculotomies performed since April 1979.20–22 Follow-up times average 6.16 years, ranging from 1 month to 7.4 years. Definitive control of vertigo has been achieved in 68.3% of patients. Hearing was made worse in 35.2% (as defined by AAOHNS criteria4 of either 15 dB loss in pure tone average or 15% loss in speech discrimination). Postoperative profound sensorineural hearing loss occurred in 11%.

The success rates reported for either internal or external endolymphatic shunt procedures should be viewed with some caution. In a review of 834 articles published on Meniere’s disease between 1952 and 1975, Torok23 found that almost without exception, advocates of either medical or surgical treatment reported success rates of 60% to 80%. Not only is there a strong placebo effect, but also sudden prolonged remission of symptoms are characteristic of Meniere’s disease. Some patients who had vertiginous attacks on a weekly basis (or more often) had a total cessation of attacks after cochleosacculotomy. In the management of disabling Meniere’s disease, cochleosacculotomy is a useful alternative to vestibular nerve section and labyrinthectomy in selected cases.

1. Schuknecht H.F., Gulya A.J. Endolymphatic hydrops: An overview and classification. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1983;92(Suppl 106):1-20.

2. Schuknecht H.F. Ménière’s disease: A correlation of symptomatology and pathology. Laryngoscope. 1963;73:651-665.

3. Dohlman G.F. On the mechanism of the Ménière attack. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1976;212:301-307.

4. Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium. Report of Subcommittee on Equilibrium and its Measurement: Ménière’s disease: Criteria for diagnosis and evaluation of therapy for reporting. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1972;76:1462-1464.

5. Fick I.A. van N: Decompression of the labyrinth: A new surgical procedure for Ménière’s disease. Arch Otolaryngol. 1964;79:447-458.

6. Fick I.A., van N. Ménière’s disease: Aetiology and a new surgical approach-sacculotomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1966;80:288-306.

7. Cody D.T.R., Simonton K.M., Hallberg O.E. Automatic repetitive decompression of the saccule in endolymphatic hydrops (tack operation): Preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 1967;77:1480-1501.

8. Cody D.T.R. The tack operation for endolymphatic hydrops. Laryngoscope. 1969;79:1737-1744.

9. Pulec J.L. Ménière’s disease: The otic-perotic shunt. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1968;1:643-648.

10. Schuknecht H.F. Cochleosacculotomy for Ménière’s disease: Theory, technique, and results. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:853-858.

11. Schuknecht H.F. Pathology of Ménière’s disease as it relates to the sac and tack procedures. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:677-682.

12. Duval A.J.III, Rhodes V.T. Ultrastructure of the organ of Corti following intermixing of cochlear fluids. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1967;76:688-708.

13. Kimura R.S., Schuknecht H.F. Effect of fistulae on endolymphatic hydrops. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1975;84:271-286.

14. Schuknecht H.F., Neff W.D. Hearing losses after apical lesions in the cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh). 1952;42:263-274.

15. Schuknecht H.F., Sutton S. Hearing losses after experimental lesions in basal coil of cochlea. Arch Otolaryngol. 1953;57:129-142.

16. Schuknecht H.F. Seifi A El: Experimental observations on the fluid physiology of the inner ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1963;72:687-721.

17. Kimura R.S., Schuknecht H.F., Ota C.Y., Jones D.D. Experimental study of sacculotomy in endolymphatic hydrops. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1977;217:123-137.

18. Schuknecht H.F., Rüther A. Blockage of longitudinal flow in endolymphatic hydrops. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1991;248:209-217.

19. Tumarkin A. Otolithic catastrophe: A new syndrome. BMJ. 1936;2:175-177.

20. Schuknecht H.F. Cochlear endolymphatic shunt. Am J Otol. 1984;5:546-548.

21. Schuknecht H.F., Bartley M. Cochlear endolymphatic shunt for Ménière’s disease. Am J Otol. 1985;6(Suppl):20-22.

22. Schuknecht H.F. Cochleosacculotomy for Ménière’s disease: Internal endolymphatic shunt. Op Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;2:35-37.

23. Torok N. Old and new in Ménière’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:1870-1877.