CHAPTER 120 Coccydynia

INTRODUCTION

Although coccygeal pain was first described in relation to a fracture by sixteenth-century French surgeon Ambroise Paré, the term coccydynia was not introduced until 1859 by Simpson.1 The awareness of this condition led to numerous studies, but it has remained poorly understood until recently. The use of dynamic films, described by the author in 1992, has led to a better understanding of the various possible causes of coccydynia and their associated specific symptoms and therefore to a better management.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY OF THE COCCYX

Very little information is available in the literature regarding coccyx anatomy. According to Gray, the sacrococcygeal joints are very thin intervertebral discs of fibrocartilage and the intercoccygeal joints can be either synovial joints or discs.2

By examining nine aged coccyges from fresh cadavers, the author found that the sacrococcygeal joint was a disc in one case, a synovial joint in four cases and, in the four remaining cases, an intermediate structure composed of a disc containing a fairly extensive cleft, parallel to the endplates, and bordered by annular fibers or synovial cells.3 This intermediate pattern was not found in the intercoccygeal joints. It is unknown if the same distribution is found in young individuals, which raises the question as to whether the cleft extends throughout life as a result of mechanical constraints, with the disc gradually changing to a synovial joint in the same individual. Synovial joints allow more mobility than discs. A fourth type found consisted of complete ossification of the sacrococcygeal joint. A study of two different populations found the frequency of this type to be 22% and 68% of the cases, respectively.4 In some instances, the entire coccyx was ossified.

The physiological movements of the coccyx are restricted to flexion and extension. Active flexion (movement in a forward direction) is performed by the levator ani and the external sphincter muscles. Extension (movement in a backward direction) is caused by a relaxation of these muscles and increased intra-abdominal pressure, which occurs during defecation and parturition.5 It is always a passive movement. To the best of the author’s knowledge, the movements of the coccyx in the sitting position have never been reported in the literature. They consist either of flexion (moving forward) or extension (moving backward) or a lack of mobility (rigid coccyx).

The angle of incidence determines the direction of sagittal movement of the coccyx. The author has described the coccygeal incidence as the angle at which the coccyx strikes the seat when the subject sits down.6 If the incidence is low, the coccyx will be more or less parallel to the seat surface. The pressure exerted by the seat will push the coccyx forward and upward in flexion. If the angle of incidence is high, the coccyx will be somewhat perpendicular to the seat surface. The coccyx will then be pushed backward in extension by increased intrapelvic pressure. The incidence is influenced by the shape of the coccyx and the sagittal pelvic rotation.7 Coccyges with more than two vertebrae are often curved and long, and have a low incidence. Conversely, straight, short coccyges have a higher incidence. Four types of coccyx have been described according to the Postacchini and Massobrio8 classification ranging from the straightest (type I) to the most sharply angled coccyx (hooked coccyx, type IV). The coccygeal shape can also be determined by measuring the intercoccygeal9 or sacrococcygeal angle (Maigne), this latter formed by the intersection of the coccygeal and the 4th sacral vertebra axis. A sacrococcygeal angle close to 180° corresponds to a straight coccyx while a curved coccyx will have an angle close to 90°. The incidence is related to another angle; the degree of sagittal pelvic rotation. This angle measures the sagittal rotation of the pelvis when the subject moves from the standing to the sitting position. This rotation is accompanied with reduction of lumbar lordosis. When the sagittal pelvic rotation is high (up to 60°), the incidence is low. This is usually observed in subjects with a normal or low body mass index (BMI). Conversely, when the pelvic rotation is low (less than 30°), the incidence is high. This is the case in subjects with high BMI (>27). It is believed that the pelvic volume in obese subjects restricts the natural movements of pelvic rotation. Other factors can restrict pelvic rotation, including loss of mobility of the lumbosacral junction as a result of degenerative disc changes, sequelae of discectomy and arthrodesis, or, more simply, a high seat. Hyperlaxity of the ligaments and a low seat can also increase rotation. Such factors can affect the occurrence of coccygeal pain.

HISTORICAL ASSESSMENT

Interviewing the patient with coccydynia should include the following four steps:

Confirm the diagnosis: where do you feel the pain?

It is therefore essential to ask the patient to turn his or her back toward the examiner and point to the painful area. The identified region must correspond to the coccyx. Diffuse pain or pain present in both the standing and sitting positions does not indicate common coccydynia. Frequent differential diagnoses include pain associated with depression, low back pain radiating to the coccyx, pudendal neuralgia, anal pathology, or certain sacroiliac pains.

Identify a cause

Trauma is a classical cause of coccydynia. Sometimes, patients blame a traumatic event sustained several years earlier, although the role of this past event is questionable. Based on the fact that luxation (see below) is the most commonly observed condition after a trauma, it was demonstrated that the interval between the trauma and the onset of coccydynia is a determining factor.7 A very short or nonexistent interval (such as in postpartum coccydynia) is almost certainly indicative of trauma-related pain. Traumatic coccydynia is very likely if the pain occurs within a month of an injury. After 3 months, it is unlikely that trauma is the cause. It is important to know whether the traumatic event is an occupational injury or not, as the treatment results may be less effective when the trauma is work related.

In some cases, coccydynia may develop after moderate trauma, as a result of a long car journey, or riding a bicycle or a horse. In obese patients, excess weight in conjunction with the particular way of changing from standing to sitting (see below), and even sitting itself can be considered as repeated microtraumas. Generally, post-traumatic coccydynia is more frequent in straight coccyges that move into extension when the subject sits down than in curved coccyges that move into flexion.7,9 Curved coccyges are actually relatively well protected during the impact of sitting. Thus, contrary to a common opinion, hooked coccyges are less at risk than straight ones regarding post-traumatic coccygodynia.

Apart from a possible trauma, it has been shown that other factors such as BMI and the presence of pain when standing up from sitting could have diagnostic value.6 Determining body mass index is essential, as this factor greatly affects coccygeal biomechanics and, therefore, the culprit lesion. Luxation is more frequently observed in the obese population. The obese subject has a low angle of sagittal pelvic rotation when sitting down. As a result, the coccyx is more or less perpendicular to the seat surface, which increases the risk of luxation. In a normal-weight or lean person, the angle of sagittal pelvic rotation is greater, and the coccyx is parallel to the seat and prone to flexion and hypermobility. In lean patients, a spicule may cause significant irritation due to the absence of perineal fat (see below).

PAIN ON STANDING UP FROM SITTING The presence of sharp pain on passing from the sitting to the standing position is a sign that suggests a lesion that can be identified with radiologic imaging. These radiographic abnormalities are usually luxation or osseous spicules.7 As with any information gleaned during history taking, this element is of greater value if the patient mentions it spontaneously.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The rest of the consultation should be focused upon the radiologic procedure and the therapeutic management. An etiologic diagnosis is sometimes possible at this stage. Failing this, it may be possible to identify elements suggesting the presence of a radiologic lesion (Table 120.1).

Table 120.1 Clinical Elements Suggesting the Presence of a Radiologic Lesion on Dynamic Films Versus no Lesion

| Items Suggesting a Radiologic Lesion | Items Suggesting Normal Radiographs |

|---|---|

| Local coccygeal pain | Pain radiating to the buttocks and thighs |

| Pain only in the sitting position | Significant pain also present in the standing position |

| Pain on standing up from sitting (especially if mentioned spontaneously) | Absence of pain on standing up from sitting |

| Pain occurring immediately after sitting down | Pain occurring after 30–60 minutes of sitting |

| Painful sitting position from the beginning of the day | Painful sitting position especially at the end of the day |

| Pain relieved for at least a month by a steroid injection | Pain unresponsive to a steroid injection |

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

Standard radiographs

Fractures

Coccygeal fractures are very rare (two in a thousand according to the author’s findings, where the fracture only involved the first coccygeal vertebra). This is easily understood as the weak point of the coccyx is the sacrococcygeal or intercoccygeal joint and not the coccyx itself. Luxation is the most common trauma-related injury. However, fractures of the distal portion of the sacrum are slightly more common (1% in the author’s cases). The real figure may be higher, as most of the author’s patients are referred with chronic coccydynia. Fractures are only responsible for acute coccydynia, since they resolve spontaneously, typically within 3 weeks. Pseudoarthrosis seems to be exceedingly rare as this entity has never been observed in the author’s patients.

Dynamic radiographs

Since coccydynia is more pronounced in the sitting position, it is essential to compare lateral sitting and lateral standing radiographs when evaluating chronic coccydynia. Radiographs should be taken immediately when there is a history of violent trauma or acute pain. The author has termed this examination ‘dynamic exploration.’10 The author has had the opportunity to evaluate in excess of a thousand cases in this manner.

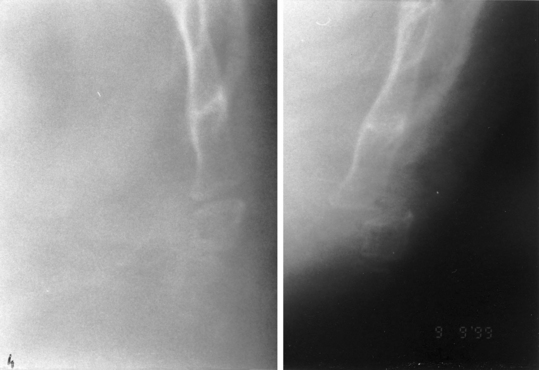

The lateral standing X-ray is taken first. In order for the coccyx to be in a neutral position, it is important that the patient avoids sitting for the 5–10 minutes preceding the X-ray examination. Otherwise, in some cases of hypermobility or luxation, there is not enough time for the coccyx to regain a neutral position. Next, the patient sits on a hard stool with the feet on a footrest (if necessary) so that the thighs are horizontal (as in the usual sitting position) until pain is experienced (Fig. 120.1). If necessary, the subject can lean slightly backward to feel the pain. If the pain cannot be triggered after a few minutes, interpretation of the sitting film will be difficult, since it has been taken in a position of no pain. The radiograph must then be taken in the sitting position, the position that regularly provokes the most intense pain for that patient.

The two radiographs are read separately to compare the general appearance, number of vertebrae, curves, sacrococcygeal and intercoccygeal joints, and the presence of a possible fracture, or coccygeal spicule. The two films are then superimposed over a bright source of light, with both sacrums superimposed upon each other to compare and measure sagittal movement of the coccyx (Fig. 120.2).

Angle of mobility

It is possible to determine the angle of coccygeal mobility, the apex of which is in the center of the first mobile disc. In two-thirds of cases, coccygeal movement is forward (flexion). Normal values in a control group range from 0° to 25°. An angle of mobility exceeding 30° in women (25° in men) is abnormal.6 In one-third of cases, the coccyx moves backward (extension), resulting in an angle of usually less than 15°. This angle can be increased to 20° only in exceptional cases. As the angle of mobility is the one of greatest importance, it should be measured systematically, except in cases of luxation, which precludes its measurement and is therefore irrelevant. Other angles differ from the angle of mobility, as their significance is purely biomechanical.

Lesions observed on dynamic radiographs

Posterior coccygeal luxation

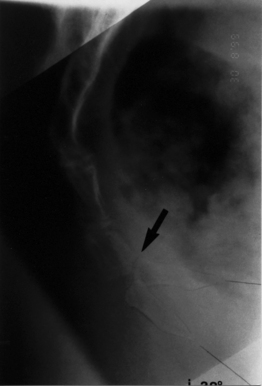

Luxation is the most striking coccygeal lesion (Fig. 120.3). It represents about 20% of the chronic coccydynia cases. Except in very rare cases of permanent luxation, it occurs only in the sitting position, and spontaneously reduces when the patient stands up. This explains why such a lesion had not been identified prior to the author’s findings. Luxation occurs on straight coccyges, with limited pelvic rotation and a greater angle of incidence. Sacrococcygeal and intercoccygeal discs are equally affected. The coccyx always moves backward. A control-group analysis showed that its displacement had to exceed 20% (based on a measurement method used for spondylolisthesis) to be significant.11 Generally, the backward movement ranges from 50% to 100%, and its implication in pain is almost never an issue.

Hypermobility

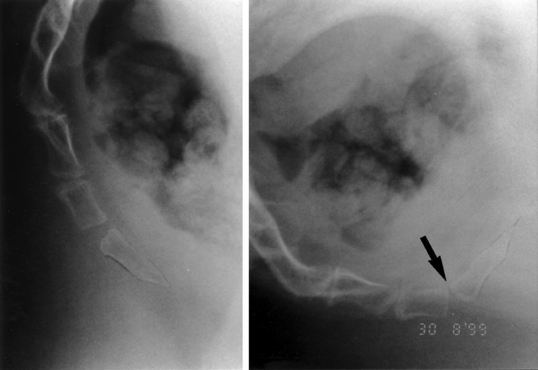

Hypermobility is defined by coccygeal flexion exceeding 30° in the sitting position.6 It is often associated with impaction of the anterior portion of the two distal vertebrae (Fig. 120.4) and/or a discrete forward displacement of the last vertebra of the coccyx, forming a small step in the sitting position (Fig. 120.5). It is found in 25% of chronic coccydynia cases. Typically, hypermobility is observed in patients with high sagittal pelvic rotation, in which the coccyx (usually curved) faces the seat surface somewhat horizontally, resulting in an incidence of less than 35°. Hypermobility is almost exclusively found in women.

Hypermobility is more frequent in normal-weighted or lean subjects. It is the particular way the coccyx comes into contact with the seat when these subjects sit down that triggers this disorder. Such patients exhibit a considerable degree of pelvic rotation that pushes the coccyx into a position parallel to the seat increasing flexion forces. Hypermobility is rarely post-traumatic, but can be associated with diffuse ligamentous hyperlaxity. Hypermobility and anterior luxation (5% of cases) are related, as they have the same biomechanical characteristics. Indeed, anterior luxation involves the same type of coccyges and only the most distal coccygeal vertebra is involved.

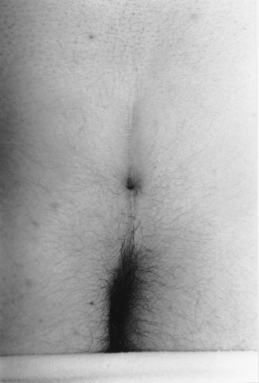

Coccygeal spicules

The spicule is a bony excrescence that can be palpated at the tip of the coccyx, jutting out under the skin (Fig. 120.6). It can cause irritation to the subcutaneous tissues during sitting. In some instances inflammation in the form of a bursitis can develop. It accounts for 15% of all causes of coccydynia. Spicules are more frequent in long and curved coccyges.7 In nearly 80% of cases, there is a skin abnormality over the spicule: a somewhat distinct pit, or, more rarely, a frank pilonidal sinus (Fig. 120.7).

Fig. 120.7 Skin pit or a real pilonidal sinus, and coccygeal spicule often form a ‘mirror-image’ pattern.

A pit or a pilonidal sinus associated with a spicule can be considered as a mirror lesion, indicating an embryologic origin of the malformation, with two poorly separated embryonic layers. Dynamic films show that spicules are most commonly seen in immobile coccyges, in which the pressure from the spicule is made worse by the inability of the coccyx to take evasive action when sitting. The spicule itself is sometimes difficult to visualize. Sometimes, a multiplanar reformatted CT scan is used to visualize the spicule. Currently, MRI is the imaging test of choice when the radiographs are indeterminate (Fig. 120.8).

Other causes in the absence of radiologic lesion

Dynamic radiographs taken while pain is present

If the familiar pain is present, but no abnormality of coccygeal mobility can be documented, then no conclusive etiology can be made from the dynamic films. Nearly half of these patients, i.e. 15% of the total, respond well to intradiscal steroid injection, a fact which tends to substantiate the presence of intradiscal inflammation. Other patients respond to a steroid injection administered at the tip of coccyx, although no spicule is visible on radiographs. Such cases probably reflect apical bursitis on immobile coccyges, where the pain is localized at the tip.

LUMBAR PAIN AND COCCYDYNIA

Pain referred from the lumbosacral area

A coccygeal pain can be referred from a lumbosacral condition (L4–5 or L5–S1).12 In such cases, the pain in the coccygeal area is exacerbated by lumbar movements (bending over or coughing) rather than sitting. Discogenic low back pain may be felt only in the sitting position and may, thus, be confused with real coccydynia. In these cases, pain in the coccygeal area has developed with or soon after the occurrence of low back pain, but never before. Such pain is a lumbar pain radiating to the coccyx, and is not related to the coccyx itself.

TREATMENT OF COCCYDYNIA

Coccygeal injections

Pericoccygeal injection had been used long before the author’s studies, and the benefit of this method is significant.13–15 The author has designed a technique for intradiscal injection under fluoroscopic control, and has described how to select the disc to be injected.

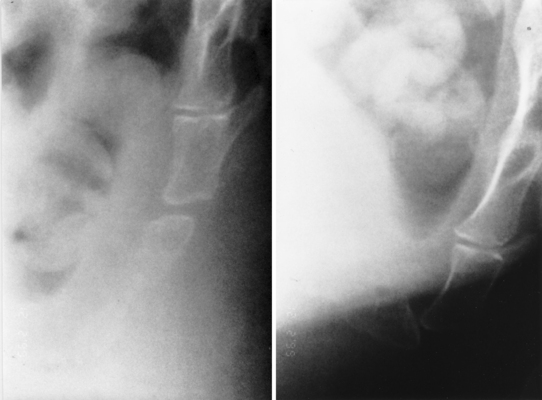

Technique of intradiscal injection

This injection can reasonably be conducted only under fluoroscopic control. The patient lies on the left side, hips and knees flexed. The disc that needs to be injected can be identified in two ways. If dynamic films confirm luxation or hypermobility, the responsible disc is obvious to the clinician. Conversely, if moderate hypermobility or no radiologic lesions are uncovered, careful palpation of the coccyx from the lower extremity of the sacrum to the tip of the coccyx will help determine the most painful site. The area is then marked with a paperclip or other radiopaque marker, to verify correct positioning during fluoroscopy. The marker is aligned to rest at the midline of the involved site. A felt pen then marks the intended site of needle puncture. The skin is then carefully disinfected with alcohol and then iodine. A local anesthetic is administered with a thin subcutaneous needle. The center of the disc is then entered with a 23-gauge, 25 mm needle. In obese patients, a 50 mm needle is necessary. The procedure can be difficult sometimes. Small osteophytes can impede advancement of the needle or force it to deviate laterally. Fluoroscopic imaging from the posteroanterior and lateral planes will demonstrate incorrect needle placement. The ideal terminal location is at the center of the symptomatic disc. The needle should not be pushed too ventral as the potential space anterior to the most ventral aspect of the disc is only 5 mm. The approximating structure is the rectal wall. The author usually injects a small amount of dye during coccygeal discography (Fig. 120.9). This allows for confirmation of needle position. In some instances the familiar pain can even be elicited, but the author considers such provocation to be an unreliable indicator of whether the diagnosis is accurate. Examination is completed with the injection of approximately 2 mL of a glucocorticoid. At the next follow-up visit the vast majority of patients describe complete relief of their symptoms. The author has observed no serious complications in over 2000 injections. Despite the safe record, theoretical mishaps must be kept in mind, including iodine allergy, infection, or perforation of the posterior rectal wall.

Results

Response to injection is generally slow, especially at the coccygeal tip. The injection benefit is generally assessed 3 weeks later and will persist up to 3 months with good to excellent results in 75% of the cases.16 After 3 months, the results may decline, with relapse in one-third of patients. In the case of relapse, a second injection may be performed. If the relief is longer after the second injection, then treatment with local injections may have a good overall outcome. If the relief is shorter, injections are discontinued and another treatment is then considered. At 1 year, treatment by injection is effective in 65% of cases (good to excellent results), a figure which makes it the first line of conservative treatment. The author reserves it for chronic coccydynia (more than 2 months’ duration). Posterior luxations respond less well, with only 50% of good/excellent results. The best results (80%) are obtained in patients with spicules.

Manual treatment

Manual treatment is the most ancient treatment of coccydynia. Standard techniques include levator ani massage,17 joint mobilization with the coccyx in extension,18 and levator ani stretching.19 These maneuvers are performed via intrarectal route over three to four sessions within a 2-week interval. A study of manual treatment conducted by the author gave an overall success rate of 25% at 6 months, which remained stable at the 2-year review date.19 A placebo-controlled study, which has not yet been published, reveals slightly better results in patients who had manual treatment than in a placebo group (efficacy was proven in 22% of cases versus 12%, respectively), which confirmed a significant difference between the two groups. Logically, the results of manual treatment vary with the cause of coccydynia. Patients with a rigid coccyx do least well; those with a normally mobile coccyx do best. Patients with luxation or hypermobility have in-between results. Coccydynia resulting from a rigid coccyx is often due to bursitis at the tip of the coccyx, whether a spicule is present or not. Given that such a lesion is inflammatory in nature, it is expected that it would respond to manual treatment.

Surgical treatment

Coccygectomy has long been controversial, despite the good results reported in the literature. However, the author feels that the controversy has evolved because of ill-defined selection criteria. Patients with disabling pain and dynamic radiographs demonstrating coccygeal instability, which includes luxation and hypermobility, represent the objective criteria used for the selection of surgical cases in the author’s study, and the results were excellent.20 In 90% of cases, results were good to excellent. Improvement was experienced in 2–3 months, although it took 6–10 months in some cases. In very few cases, definitive improvement was not described until 1–2 years postoperatively. This fairly long delay could be due to deafferentation pain (phantom limb syndrome). In cases of occupational injury or litigation, the outcome may be negative. A recent review of patients treated by coccygectomy for disabling instability showed that these who have responded positively to an injection (at least for a short period of time, i.e. 4 weeks) had a better outcome than those who failed to respond. The author recently extended the indication for coccygectomy to poorly tolerated spicules, provided that the patient responded to steroid injection at least once (but with a short interval of pain relief). These results are currently being assessed.

CONCLUSION

As anticipated by Howorth,21 the study of coccygeal pathology has shown that the mechanisms of coccydynia are, in their majority, comparable to those encountered in peripheral joint lesions, and not due to hysteria, a diagnosis which is offensive for the patient.

1 Sugar O. Coccyx, the bone named for a bird. Spine. 1995;20:379-383.

2 Gray H. Gray’s anatomy, 35th edn. Edinburgh: Longman, 1973.

3 Maigne JY, Molinié V, Fautrel B. Anatomie des disques sacro et inter-coccygiens. Revue de Médecine Orthopédique. 1992;28:34-35.

4 Saluja PG. The incidence of ossification of the sacrococcygeal joint. J Anat. 1988;156:11-15.

5 Smout CF, Jacoby F, Lillie EW. Gynaecological and obstetrical anatomy, 12th edn. Oxford, New-York, Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1969.

6 Maigne JY, Tamalet B. Standardized radiologic protocol for the study of common coccydynia and characteristics of the lesions observed in the sitting position. Spine. 1996;21:2588-2593.

7 Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine. 2000;25:3072-3079.

8 Postacchini F, Massobrio M. Idiopathic coccygodynia: analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. J Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65A:1116-1124.

9 Kim NH, Suk KS. Clinical and radiological differences between traumatic and idiopathic coccygodynia. Yonsei Med J. 1999;40:215-220.

10 Maigne JY, Guedj S, Fautrel B. Coccygodynies: intérêt des radiographies dynamiques de profil en station assise. Rev Rhum Mal Ostéoartic. 1992;59:28-31.

11 Maigne JY, Guedj S, Straus C. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Lateral roentgenograms in the sitting position and coccygeal discography. Spine. 1994;19:930-934.

12 Nelson DA. Idiopathic coccygodynia and lumbar disk disease: Historical correlations and clinical cautions. Perspect Biol Med. 1991;34:229-238.

13 Jurmand SH. Les injections péridurales dans le traitement de la coccygodynie. Rev Rhum Mal Ostéoartic. 1976;43:217-220.

14 Kersey PJ. Non-operative management of coccygodynia. Lancet. 1980;1(8163):318.

15 Wray C, Easom S, Hoskinson J. Coccydynia. Aetiology and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:335-338.

16 Rouhier B. Résultats des injections coccygiennes dans le traitement de la coccygodynie chronique. Thèse d’université. Paris V, 2003.

17 Thiele GH. Coccydynia and pain in the superior gluteal region. JAMA. 1937;109:1271-1275.

18 Maigne R. Les manipulations vertébrales, 3rd edn., Paris: Expansion Scientifique Française; 1961:180.

19 Maigne JY, Chatellier G. Comparison of three manual coccydynia treatments. Spine. 2001;26:E479-E484.

20 Maigne JY, Lagauche D, Doursounian L. Instability of the coccyx in coccydynia. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B:1038-1041.

21 Howorth B. The painful coccyx. Clin Orthop. 1959;14:145-150.