A. Excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation), occurring more days than not for at least 6 months, about a number of events or activities (such as work or school performance).

B. The individual finds it difficult to control the worry.

C. The anxiety and worry are associated with three (or more) of the following six symptoms (with at least some symptoms present for more days than not for the past 6 months): (1) restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge; (2) being easily fatigued; (3) difficulty concentrating or mind going blank; (4) irritability; (5) muscle tension; (6) sleep disturbance (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restless, unsatisfying sleep).

D. The anxiety, worry, or physical symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

E. The disturbance is not attributable to the physiologic effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism).

F. The disturbance is not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., anxiety or worry about having panic attacks in panic disorder, negative evaluation in social anxiety disorder [social phobia], contamination or other obsessions in obsessive-compulsive disorder, separation from attachment figures in separation anxiety disorder, reminders of traumatic events in posttraumatic stress disorder, gaining weight in anorexia nervosa, physical complaints in somatic symptom disorder, perceived appearance flaws in body dysmorphic disorder, having a serious illness in illness anxiety disorder, or the content of delusional beliefs in schizophrenia or delusional disorder).

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Etiology and Pathophysiology All anxiogenic agents act on the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor/chloride ion channel complex, implicating this neurotransmitter system in the pathogenesis of anxiety and panic attacks. Benzodiazepines are thought to bind two separate GABAA receptor sites: type I, which has a broad neuroanatomic distribution, and type II, which is concentrated in the hippocampus, striatum, and neocortex. The antianxiety effects of the various benzodiazepines are influenced by their relative binding to alpha 2 and 3 subunits of the GABAA receptor, and sedation and memory impairment to the alpha 1 subunit, Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) and 3α-reduced neuroactive steroids (allosteric modulators of GABAA) also appear to have a role in anxiety, and buspirone, a partial 5-HT1A receptor agonist, and certain 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor antagonists (e.g., nefazodone) may have beneficial effects.

PHOBIC DISORDERS

Clinical Manifestations The cardinal feature of phobic disorders is a marked and persistent fear of objects or situations, exposure to which results in an immediate anxiety reaction. The patient avoids the phobic stimulus, and this avoidance usually impairs occupational or social functioning. Panic attacks may be triggered by the phobic stimulus or may occur spontaneously. Unlike patients with other anxiety disorders, individuals with phobias usually experience anxiety only in specific situations. Common phobias include fear of closed spaces (claustrophobia), fear of blood, and fear of flying. Social phobia is distinguished by a specific fear of social or performance situations in which the individual is exposed to unfamiliar individuals or to possible examination and evaluation by others. Examples include having to converse at a party, use public restrooms, and meet strangers. In each case, the affected individual is aware that the experienced fear is excessive and unreasonable given the circumstance. The specific content of a phobia may vary across gender, ethnic, and cultural boundaries.

Phobic disorders are common, affecting ~7–9% of the population. Twice as many females are affected than males. Full criteria for diagnosis are usually satisfied first in early adulthood, but behavioral avoidance of unfamiliar people, situations, or objects dating from early childhood is common.

In one study of female twins, concordance rates for agoraphobia, social phobia, and animal phobia were found to be 23% for monozygotic twins and 15% for dizygotic twins. A twin study of fear conditioning, a model for the acquisition of phobias, demonstrated a heritability of 35–45%. Animal studies of fear conditioning have indicated that processing of the fear stimulus occurs through the lateral nucleus of the amygdala, extending through the central nucleus and projecting to the periaqueductal gray region, lateral hypothalamus, and paraventricular hypothalamus.

STRESS DISORDERS

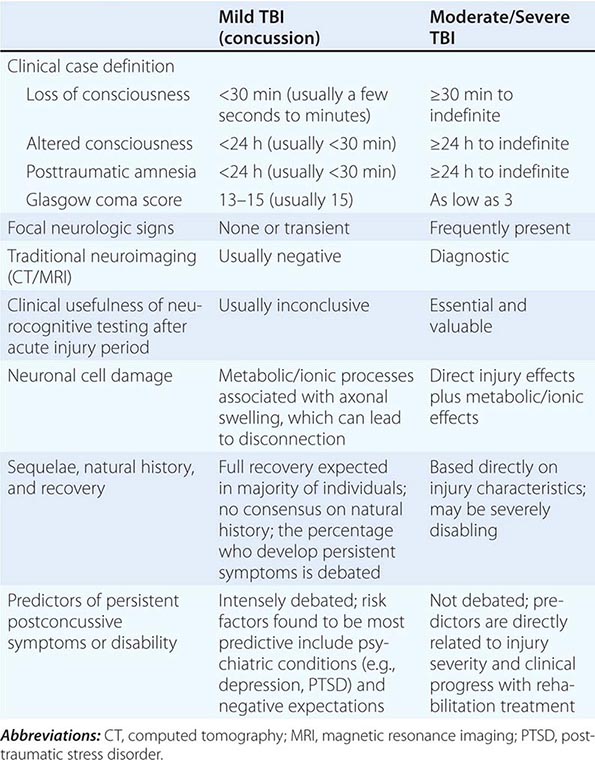

Clinical Manifestations Patients may develop anxiety after exposure to extreme traumatic events such as the threat of personal death or injury or the death of a loved one. The reaction may occur shortly after the trauma (acute stress disorder) or be delayed and subject to recurrence (PTSD) (Table 466-6). In both syndromes, individuals experience associated symptoms of detachment and loss of emotional responsivity. The patient may feel depersonalized and unable to recall specific aspects of the trauma, although typically it is reexperienced through intrusions in thought, dreams, or flashbacks, particularly when cues of the original event are present. Patients often actively avoid stimuli that precipitate recollections of the trauma and demonstrate a resulting increase in vigilance, arousal, and startle response. Patients with stress disorders are at risk for the development of other disorders related to anxiety, mood, and substance abuse (especially alcohol). Between 5 and 10% of Americans will at some time in their life satisfy criteria for PTSD, with women more likely to be affected than men.

|

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER |

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Risk factors for the development of PTSD include a past psychiatric history and personality characteristics of high neuroticism and extroversion. Twin studies show a substantial genetic influence on all symptoms associated with PTSD, with less evidence for an environmental effect.

Etiology and Pathophysiology It is hypothesized that in PTSD there is excessive release of norepinephrine from the locus coeruleus in response to stress and increased noradrenergic activity at projection sites in the hippocampus and amygdala. These changes theoretically facilitate the encoding of fear-based memories. Greater sympathetic responses to cues associated with the traumatic event occur in PTSD, although pituitary adrenal responses are blunted.

OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER

Clinical Manifestations Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors that impair everyday functioning. Fears of contamination and germs are common, as are handwashing, counting behaviors, and having to check and recheck such actions as whether a door is locked. The degree to which the disorder is disruptive for the individual varies, but in all cases, obsessive-compulsive activities take up >1 h per day and are undertaken to relieve the anxiety triggered by the core fear. Patients often conceal their symptoms, usually because they are embarrassed by the content of their thoughts or the nature of their actions. Physicians must ask specific questions regarding recurrent thoughts and behaviors, particularly if physical clues such as chafed and reddened hands or patchy hair loss (from repetitive hair pulling, or trichotillomania) are present. Comorbid conditions are common, the most frequent being depression, other anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and tics. OCD has a lifetime prevalence of 2–3% worldwide. Onset is usually gradual, beginning in early adulthood, but childhood onset is not rare. The disorder usually has a waxing and waning course, but some cases may show a steady deterioration in psychosocial functioning.

Etiology and Pathophysiology A genetic contribution to OCD is suggested by twin studies, but no susceptibility gene for OCD has been identified to date. Family studies show an aggregation of OCD with Tourette’s disorder, and both are more common in males and in first-born children.

The anatomy of obsessive-compulsive behavior is thought to include the orbital frontal cortex, caudate nucleus, and globus pallidus. The caudate nucleus appears to be involved in the acquisition and maintenance of habit and skill learning, and interventions that are successful in reducing obsessive-compulsive behaviors also decrease metabolic activity measured in the caudate.

MOOD DISORDERS

Mood disorders are characterized by a disturbance in the regulation of mood, behavior, and affect. Mood disorders are subdivided into (1) depressive disorders, (2) bipolar disorders, and (3) depression in association with medical illness or alcohol and substance abuse (Chaps. 467 through 471e). Major depressive disorder (MDD) is differentiated from bipolar disorder by the absence of a manic or hypomanic episode. The relationship between pure depressive syndromes and bipolar disorders is not well understood; MDD is more frequent in families of bipolar individuals, but the reverse is not true. In the Global Burden of Disease Study conducted by the World Health Organization, unipolar major depression ranked fourth among all diseases in terms of disability-adjusted life-years and was projected to rank second by the year 2020. In the United States, lost productivity directly related to mood disorders has been estimated at $55.1 billion per year.

DEPRESSION IN ASSOCIATION WITH MEDICAL ILLNESS

Depression occurring in the context of medical illness is difficult to evaluate. Depressive symptomatology may reflect the psychological stress of coping with the disease, may be caused by the disease process itself or by the medications used to treat it, or may simply coexist in time with the medical diagnosis.

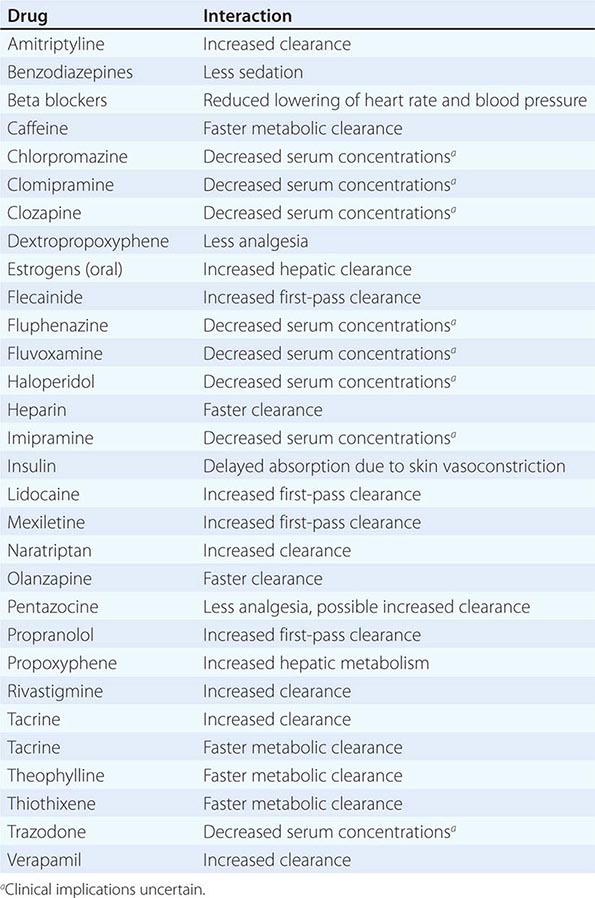

Virtually every class of medication includes some agent that can induce depression. Antihypertensive drugs, anticholesterolemic agents, and antiarrhythmic agents are common triggers of depressive symptoms. Iatrogenic depression should also be considered in patients receiving glucocorticoids, antimicrobials, systemic analgesics, antiparkinsonian medications, and anticonvulsants. To decide whether a causal relationship exists between pharmacologic therapy and a patient’s change in mood, it may sometimes be necessary to undertake an empirical trial of an alternative medication.

Between 20 and 30% of cardiac patients manifest a depressive disorder; an even higher percentage experience depressive symptomatology when self-reporting scales are used. Depressive symptoms following unstable angina, myocardial infarction, cardiac bypass surgery, or heart transplant impair rehabilitation and are associated with higher rates of mortality and medical morbidity. Depressed patients often show decreased variability in heart rate (an index of reduced parasympathetic nervous system activity), which may predispose individuals to ventricular arrhythmia and increased morbidity. Depression also appears to increase the risk of developing coronary heart disease, possibly through increased platelet aggregation. TCAs are contraindicated in patients with bundle branch block, and TCA-induced tachycardia is an additional concern in patients with congestive heart failure. SSRIs appear not to induce ECG changes or adverse cardiac events and thus are reasonable first-line drugs for patients at risk for TCA-related complications. SSRIs may interfere with hepatic metabolism of anticoagulants, however, causing increased anticoagulation.

In patients with cancer, the mean prevalence of depression is 25%, but depression occurs in 40–50% of patients with cancers of the pancreas or oropharynx. This association is not due to the effect of cachexia alone, as the higher prevalence of depression in patients with pancreatic cancer persists when compared to those with advanced gastric cancer. Initiation of antidepressant medication in cancer patients has been shown to improve quality of life as well as mood. Psychotherapeutic approaches, particularly group therapy, may have some effect on short-term depression, anxiety, and pain symptoms.

Depression occurs frequently in patients with neurologic disorders, particularly cerebrovascular disorders, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, multiple sclerosis, and traumatic brain injury. One in five patients with left-hemisphere stroke involving the dorsolateral frontal cortex experiences major depression. Late-onset depression in otherwise cognitively normal individuals increases the risk of a subsequent diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. All classes of antidepressant agents are effective against these depressions, as are, in some cases, stimulant compounds.

The reported prevalence of depression in patients with diabetes mellitus varies from 8 to 27%, with the severity of the mood state correlating with the level of hyperglycemia and the presence of diabetic complications. Treatment of depression may be complicated by effects of antidepressive agents on glycemic control. MAOIs can induce hypoglycemia and weight gain, whereas TCAs can produce hyperglycemia and carbohydrate craving. SSRIs and SNRIs, like MAOIs, may reduce fasting plasma glucose, but they are easier to use and may also improve dietary and medication compliance.

Hypothyroidism is frequently associated with features of depression, most commonly depressed mood and memory impairment. Hyperthyroid states may also present in a similar fashion, usually in geriatric populations. Improvement in mood usually follows normalization of thyroid function, but adjunctive antidepressant medication is sometimes required. Patients with subclinical hypothyroidism can also experience symptoms of depression and cognitive difficulty that respond to thyroid replacement.

The lifetime prevalence of depression in HIV-positive individuals has been estimated at 22–45%. The relationship between depression and disease progression is multifactorial and likely to involve psychological and social factors, alterations in immune function, and central nervous system (CNS) disease. Chronic hepatitis C infection is also associated with depression, which may worsen with interferon-α treatment.

Some chronic disorders of uncertain etiology, such as chronic fatigue syndrome (Chap. 464e) and fibromyalgia (Chap. 396), are strongly associated with depression and anxiety; patients may benefit from antidepressant treatment or anticonvulsant agents such as pregabalin.

DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS

Clinical Manifestations Major depression is defined as depressed mood on a daily basis for a minimum duration of 2 weeks (Table 466-7). An episode may be characterized by sadness, indifference, apathy, or irritability and is usually associated with changes in sleep patterns, appetite, and weight; motor agitation or retardation; fatigue; impaired concentration and decision making; feelings of shame or guilt; and thoughts of death or dying. Patients with depression have a profound loss of pleasure in all enjoyable activities, exhibit early morning awakening, feel that the dysphoric mood state is qualitatively different from sadness, and often notice a diurnal variation in mood (worse in morning hours). Patients experiencing bereavement or grief may exhibit many of the same signs and symptoms of major depression, although the emphasis is usually on feelings of emptiness and loss, rather than anhedonia and loss of self-esteem, and the duration is usually limited. In certain cases, however, the diagnosis of major depression may be warranted even in the context of a significant loss.

|

CRITERIA FOR A MAJOR DEPRESSIVE EPISODE |

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Approximately 15% of the population experiences a major depressive episode at some point in life, and 6–8% of all outpatients in primary care settings satisfy diagnostic criteria for the disorder. Depression is often undiagnosed, and even more frequently, it is treated inadequately. If a physician suspects the presence of a major depressive episode, the initial task is to determine whether it represents unipolar or bipolar depression or is one of the 10–15% of cases that are secondary to general medical illness or substance abuse. Physicians should also assess the risk of suicide by direct questioning, as patients are often reluctant to verbalize such thoughts without prompting. If specific plans are uncovered or if significant risk factors exist (e.g., a past history of suicide attempts, profound hopelessness, concurrent medical illness, substance abuse, or social isolation), the patient must be referred to a mental health specialist for immediate care. The physician should specifically probe each of these areas in an empathic and hopeful manner, being sensitive to denial and possible minimization of distress. The presence of anxiety, panic, or agitation significantly increases near-term suicidal risk. Approximately 4–5% of all depressed patients will commit suicide; most will have sought help from physicians within 1 month of their deaths.

In some depressed patients, the mood disorder does not appear to be episodic and is not clearly associated with either psychosocial dysfunction or change from the individual’s usual experience in life. Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymic disorder) consists of a pattern of chronic (at least 2 years), ongoing depressive symptoms that are usually less severe and/or less numerous than those found in major depression, but the functional consequences may be equivalent to or even greater; the two conditions are sometimes difficult to separate and can occur together (“double depression”). Many patients who exhibit a profile of pessimism, disinterest, and low self-esteem respond to antidepressant treatment. Persistent and chronic depressive disorders occur in approximately 2% of the general population.

Depression is approximately twice as common in women as in men, and the incidence increases with age in both sexes. Twin studies indicate that the liability to major depression of early onset (before age 25) is largely genetic in origin. Negative life events can precipitate and contribute to depression, but genetic factors influence the sensitivity of individuals to these stressful events. In most cases, both biologic and psychosocial factors are involved in the precipitation and unfolding of depressive episodes. The most potent stressors appear to involve death of a relative, assault, or severe marital or relationship problems.

Unipolar depressive disorders usually begin in early adulthood and recur episodically over the course of a lifetime. The best predictor of future risk is the number of past episodes; 50–60% of patients who have a first episode have at least one or two recurrences. Some patients experience multiple episodes that become more severe and frequent over time. The duration of an untreated episode varies greatly, ranging from a few months to ≥1 year. The pattern of recurrence and clinical progression in a developing episode are also variable. Within an individual, the nature of episodes (e.g., specific presenting symptoms, frequency and duration) may be similar over time. In a minority of patients, a severe depressive episode may progress to a psychotic state; in elderly patients, depressive symptoms may be associated with cognitive deficits mimicking dementia (“pseudodementia”). A seasonal pattern of depression, called seasonal affective disorder, may manifest with onset and remission of episodes at predictable times of the year. This disorder is more common in women, whose symptoms are anergy, fatigue, weight gain, hypersomnia, and episodic carbohydrate craving. The prevalence increases with distance from the equator, and improvement may occur by altering light exposure.

Etiology and Pathophysiology Although evidence for genetic transmission of unipolar depression is not as strong as in bipolar disorder, monozygotic twins have a higher concordance rate (46%) than dizygotic siblings (20%), with little support for any effect of a shared family environment.

Neuroendocrine abnormalities that reflect the neurovegetative signs and symptoms of depression include: (1) increased cortisol and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion, (2) an increase in adrenal size, (3) a decreased inhibitory response of glucocorticoids to dexamethasone, and (4) a blunted response of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level to infusion of thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH). Antidepressant treatment leads to normalization of these abnormalities. Major depression is also associated with changes in levels of proinflammatory cytokines and neurotrophins.

Diurnal variations in symptom severity and alterations in circadian rhythmicity of a number of neurochemical and neurohumoral factors suggest that biologic differences may be secondary to a primary defect in regulation of biologic rhythms. Patients with major depression show consistent findings of a decrease in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep onset (REM latency), an increase in REM density, and, in some subjects, a decrease in stage IV delta slow-wave sleep.

Although antidepressant drugs inhibit neurotransmitter uptake within hours, their therapeutic effects typically emerge over several weeks, implicating adaptive changes in second messenger systems and transcription factors as possible mechanisms of action.

The pathogenesis of depression is discussed in detail in Chap. 465e.

BIPOLAR DISORDER

Clinical Manifestations Bipolar disorder is characterized by unpredictable swings in mood from mania (or hypomania) to depression. Some patients suffer only from recurrent attacks of mania, which in its pure form is associated with increased psychomotor activity; excessive social extroversion; decreased need for sleep; impulsivity and impairment in judgment; and expansive, grandiose, and sometimes irritable mood (Table 466-8). In severe mania, patients may experience delusions and paranoid thinking indistinguishable from schizophrenia. One-half of patients with bipolar disorder present with a mixture of psychomotor agitation and activation with dysphoria, anxiety, and irritability. It may be difficult to distinguish mixed mania from agitated depression. In some bipolar patients (bipolar II disorder), the full criteria for mania are lacking, and the requisite recurrent depressions are separated by periods of mild activation and increased energy (hypomania). In cyclothymic disorder, there are numerous hypomanic periods, usually of relatively short duration, alternating with clusters of depressive symptoms that fail, either in severity or duration, to meet the criteria of major depression. The mood fluctuations are chronic and should be present for at least 2 years before the diagnosis is made.

|

CRITERIA FOR A MANIC EPISODE |

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Manic episodes typically emerge over a period of days to weeks, but onset within hours is possible, usually in the early morning hours. An untreated episode of either depression or mania can be as short as several weeks or last as long as 8–12 months, and rare patients have an unremitting chronic course. The term rapid cycling is used for patients who have four or more episodes of either depression or mania in a given year. This pattern occurs in 15% of all patients, almost all of whom are women. In some cases, rapid cycling is linked to an underlying thyroid dysfunction, and in others, it is iatrogenically triggered by prolonged antidepressant treatment. Approximately one-half of patients have sustained difficulties in work performance and psychosocial functioning, with depressive phases being more responsible for impairment than mania.

Bipolar disorder is common, affecting ~1.5% of the population in the United States. Onset is typically between 20 and 30 years of age, but many individuals report premorbid symptoms in late childhood or early adolescence. The prevalence is similar for men and women; women are likely to have more depressive and men more manic episodes over a lifetime.

Differential Diagnosis The differential diagnosis of mania includes secondary mania induced by stimulant or sympathomimetic drugs, hyperthyroidism, AIDS, and neurologic disorders such as Huntington’s or Wilson’s disease and cerebrovascular accidents. Comorbidity with alcohol and substance abuse is common, either because of poor judgment and increased impulsivity or because of an attempt to self-treat the underlying mood symptoms and sleep disturbances.

Etiology and Pathophysiology Genetic predisposition to bipolar disorder is evident from family studies; the concordance rate for monozygotic twins approaches 80%. Patients with bipolar disorder also appear to have altered circadian rhythmicity, and lithium may exert its therapeutic benefit through a resynchronization of intrinsic rhythms keyed to the light/dark cycle.

SOMATIC SYMPTOM DISORDER

Many patients presenting in general medical practice, perhaps as many as 5–7%, will experience a somatic symptom(s) as particularly distressing and preoccupying, to the point that it comes to dominate their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs and interferes to a varying degree with everyday functioning. Although the absence of a medical explanation for these complaints was historically emphasized as a diagnostic element, it has been recognized that the patient’s interpretation and elaboration of the experience is the critical defining factor and that patients with well-established medical causation may qualify for the diagnosis. Multiple complaints are typical, but severe single symptoms can occur as well. Comorbidity with depressive and anxiety disorders is common and may affect the severity of the experience and its functional consequences. Personality factors may be a significant risk factor, as may a low level of educational or socioeconomic status or a history of recent stressful life events. Cultural factors are relevant as well and should be incorporated into the evaluation. Individuals who have persistent preoccupations about having or acquiring a serious illness, but who do not have a specific somatic complaint, may qualify for a related diagnosis—illness anxiety disorder. The diagnosis of conversion disorder (functional neurologic symptom disorder) is used to specifically identify those individuals whose somatic complaints involve one or more symptoms of altered voluntary motor or sensory function that cannot be medically explained and that causes significant distress or impairment or requires medical evaluation.

In factitious illnesses, the patient consciously and voluntarily produces physical symptoms of illness. The term Munchausen’s syndrome is reserved for individuals with particularly dramatic, chronic, or severe factitious illness. In true factitious illness, the sick role itself is gratifying. A variety of signs, symptoms, and diseases have been either simulated or caused by factitious behavior, the most common including chronic diarrhea, fever of unknown origin, intestinal bleeding or hematuria, seizures, and hypoglycemia. Factitious disorder is usually not diagnosed until 5–10 years after its onset, and it can produce significant social and medical costs. In malingering, the fabrication derives from a desire for some external reward such as a narcotic medication or disability reimbursement.

FEEDING AND EATING DISORDERS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Feeding and eating disorders constitute a group of conditions in which there is a persistent disturbance of eating or associated behaviors that significantly impair an individual’s physical health or psychosocial functioning. In DSM-5 the described categories (with the exception of pica) are defined to be mutually exclusive in a given episode, based on the understanding that although they are phenotypically similar in some ways, they differ in course, prognosis, and effective treatment interventions. Compared with DSM-IV-TR, three disorders (i.e., avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, rumination disorder, pica) that were previously classified as disorders of infancy or childhood have been grouped together with the disorders of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Binge-eating disorder is also now included as a formal diagnosis; the intent of each of these modifications is to encourage clinicians to be more specific in their codification of eating and feeding pathology.

PICA

Pica is diagnosed when the individual, over age 2, eats one or more nonnutritive, nonfood substances for a month or more and requires medical attention as a result. There is usually no specific aversion to food in general but a preferential choice to ingest substances such as clay, starch, soap, paper, or ash. The diagnosis requires the exclusion of specific culturally approved practices and has not been commonly found to be caused by a specific nutritional deficiency. Onset is most common in childhood but the disorder can occur in association with other major psychiatric conditions in adults. An association with pregnancy has been observed, but the condition is only diagnosed when medical risks are increased by the behavior.

RUMINATION DISORDER

In this condition, individuals who have no demonstrable associated gastrointestinal or other medical condition repeatedly regurgitate their food after eating and then either rechew or swallow it or spit it out. The behavior typically occurs on a daily basis and must persist for at least 1 month. Weight loss and malnutrition are common sequelae, and individuals may attempt to conceal their behavior, either by covering their mouth or through social avoidance while eating. In infancy, the onset is typically between 3 to 12 months, and the behavior may remit spontaneously, although in some it appears to be recurrent.

AVOIDANT/RESTRICTIVE FOOD INTAKE DISORDER

The cardinal feature of this disorder is avoidance or restriction of food intake, usually stemming from a lack of interest in or distaste of food and associated with weight loss, nutritional deficiency, dependency on nutritional supplementation, or marked impairment in psychosocial functioning, either alone or in combination. Culturally approved practices, such as fasting, or a lack of available food must be excluded as possible causes. The disorder is distinguished from anorexia nervosa by the presence of emotional factors, such as a fear of gaining weight and distortion of body image in the latter condition. Onset is usually in infancy or early childhood, but avoidant behaviors may persist into adulthood. The disorder is equally prevalent in males and females and is frequently comorbid with anxiety and cognitive and attention-deficit disorders and situations of familial stress. Developmental delay and functional deficits may be significant if the disorder is long-standing and unrecognized.

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Individuals are diagnosed with anorexia nervosa if they restrict their caloric intake to a degree that their body weight deviates significantly from age, gender, health, and developmental norms and if they also exhibit a fear of gaining weight and an associated disturbance in body image. The condition is further characterized by differentiating those who achieve their weight loss predominantly through restricting intake or by excessive exercise (restricting type) from those who engage in recurrent binge eating and/or subsequent purging, self-induced vomiting, and usage of enemas, laxatives, or diuretics (binge-eating/purging type). Such subtyping is more state than trait specific, as individuals may transition from one profile to the other over time. Determination of whether an individual satisfies the primary criterion of significant low weight is complex and must be individualized, using all available historical information and comparison of body habitus to international body mass norms and guidelines.

Individuals with anorexia nervosa frequently lack insight into their condition and are in denial about possible medical consequences; they often are not comforted by their achieved weight loss and persist in their behaviors despite having met previously self-designated weight goals. Recent research has identified alterations in the circuitry of reward sensitivity and executive function in anorexia and implicated disturbances in frontal cortex and anterior insula regulation of interoceptive awareness of satiety and hunger. Neurochemical findings, including the role of ghrelin, remain controversial.

Onset is most common in adolescence, although onset in later life can occur. Many more females than males are affected, with a lifetime prevalence in women of up to 4%. The disorder appears most prevalent in postindustrialized and urbanized countries and is frequently comorbid with preexisting anxiety disorders. The medical consequences of prolonged anorexia nervosa are multisystemic and can be life-threatening in severe presentations. Changes in blood chemistry include leukopenia with lymphocytosis, elevations in blood urea nitrogen, and metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia when purging is present. History and physical examination may reveal amenorrhea in females, skin abnormalities (petechiae, lanugo hair, dryness), and signs of hypometabolic function, including hypotension, hypothermia, and sinus bradycardia. Endocrine effects include hypogonadism, growth hormone resistance, and hypercortisolemia. Osteoporosis is a longer-term concern.

The course of the disorder is variable, with some individuals recovering after a single episode, while others exhibit recurrent episodes or a chronic course. Untreated anorexia has a mortality of 5.1/1000, the highest among psychiatric conditions. Maudsley family-based therapy has proven to be an effective therapy in younger individuals, with strict behavioral contingencies used when weight loss becomes critical. No pharmacologic intervention has proven to be specifically beneficial, but comorbid depression and anxiety should be treated. Weight gain should be undertaken gradually with a goal of 0.5 to 1 pound per week to prevent refeeding syndrome. Most individuals are able to achieve remission within 5 years of the original diagnosis.

BULIMIA NERVOSA

Bulimia nervosa describes individuals who engage in recurrent and frequent (at least once a week for 3 months) periods of binge eating and who then resort to compensatory behaviors, such as self-induced purging, enemas, use of laxatives, or excessive exercise to avoid weight gain. Binge eating itself is defined as excessive food intake in a prescribed period of time, usually <2 h. As in anorexia nervosa, disturbances in body image occur and promote the behavior, but unlike in anorexia, individuals are of normal weight or even somewhat overweight. Subjects typically describe a loss of control and express shame about their actions, and often relate that their episodes are triggered by feelings of negative self-esteem or social stresses. The lifetime prevalence in women is approximately 2%, with a 10:1 female-to-male ratio. The disorder typically begins in adolescence and may be persistent over a number of years. Transition to anorexia occurs in only 10–15% of cases. Many of the medical risks associated with bulimia nervosa parallel those of anorexia nervosa and are a direct consequence of purging, including fluid and electrolyte disturbances and conduction abnormalities. Physical examination often results in no specific findings, but dental erosion and parotid gland enlargement may be present. Effective treatment approaches include SSRI antidepressants, usually in combination with cognitive-behavioral, emotion regulation, or interpersonal-based psychotherapies.

BINGE-EATING DISORDER

Binge-eating disorder is distinguished from bulimia nervosa by the absence of compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain after an episode and by a lack of effort to restrict weight gain between episodes. Other features are similar, including distress over the behavior and the experience of loss of control, resulting in eating more rapidly or in greater amounts than intended or eating when not hungry. The 12-month prevalence in females is 1.6%, with a much lower female-to-male ratio than bulimia nervosa. Little is known about the course of the disorder, given its recent categorization, but its prognosis is markedly better than for other eating disorders, both in terms of its natural course and response to treatment. Transition to other eating disorder conditions is thought to be rare.

PERSONALITY DISORDERS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Personality disorders are characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, and interpersonal behavior that are relatively inflexible and cause significant functional impairment or subjective distress for the individual. The observed behaviors are not secondary to another mental disorder, nor are they precipitated by substance abuse or a general medical condition. This distinction is often difficult to make in clinical practice, because personality change may be the first sign of serious neurologic, endocrine, or other medical illness. Patients with frontal lobe tumors, for example, can present with changes in motivation and personality while the results of the neurologic examination remain within normal limits. Individuals with personality disorders are often regarded as “difficult patients” in clinical medical practice because they are seen as excessively demanding and/or unwilling to follow recommended treatment plans. Although DSM-5 portrays personality disorders as qualitatively distinct categories, there is an alternative perspective that personality characteristics vary as a continuum between normal functioning and formal mental disorder.

Personality disorders have been grouped into three overlapping clusters. Cluster A includes paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders. It includes individuals who are odd and eccentric and who maintain an emotional distance from others. Individuals have a restricted emotional range and remain socially isolated. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder frequently have unusual perceptual experiences and express magical beliefs about the external world. The essential feature of paranoid personality disorder is a pervasive mistrust and suspiciousness of others to an extent that is unjustified by available evidence. Cluster B disorders include antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic types and describe individuals whose behavior is impulsive, excessively emotional, and erratic. Cluster C incorporates avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality types; enduring traits are anxiety and fear. The boundaries between cluster types are to some extent artificial, and many patients who meet criteria for one personality disorder also meet criteria for aspects of another. The risk of a comorbid major mental disorder is increased in patients who qualify for a diagnosis of personality disorder.

SCHIZOPHRENIA

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous syndrome characterized by perturbations of language, perception, thinking, social activity, affect, and volition. There are no pathognomonic features. The syndrome commonly begins in late adolescence, has an insidious (and less commonly acute) onset, and, often, a poor outcome, progressing from social withdrawal and perceptual distortions to recurrent delusions and hallucinations. Patients may present with positive symptoms (such as conceptual disorganization, delusions, or hallucinations) or negative symptoms (loss of function, anhedonia, decreased emotional expression, impaired concentration, and diminished social engagement) and must have at least two of these for a 1-month period and continuous signs for at least 6 months to meet formal diagnostic criteria. Disorganized thinking or speech and grossly disorganized motor behavior, including catatonia, may also be present. As individuals age, positive psychotic symptoms tend to attenuate, and some measure of social and occupational function may be regained. “Negative” symptoms predominate in one-third of the schizophrenic population and are associated with a poor long-term outcome and a poor response to drug treatment. However, marked variability in the course and individual character of symptoms is typical.

The term schizophreniform disorder describes patients who meet the symptom requirements but not the duration requirements for schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder is used for those who manifest symptoms of schizophrenia and independent periods of mood disturbance. The terms “schizotypal” and “schizoid” refer to specific personality disorders and are discussed in that section. The diagnosis of delusional disorder is used for individuals who have delusions of various content for at least 1 month but who otherwise do not meet criteria for schizophrenia. Patients who experience a sudden onset of a brief (<1 month) alteration in thought processing, characterized by delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, or gross motor behavior, are most appropriately designated as having a brief psychotic disorder. Catatonia is recognized as a nonspecific syndrome that can occur as a consequence of other severe psychiatric/medical disorders and is diagnosed by the documentation of three or more of a cluster of motor and behavioral symptoms, including stupor, cataplexy, mutism, waxy flexibility, and stereotypy, among others. Prognosis depends not on symptom severity but on the response to antipsychotic medication. A permanent remission without recurrence does occasionally occur. About 10% of schizophrenic patients commit suicide.

Schizophrenia is present in 0.85% of individuals worldwide, with a lifetime prevalence of ~1–1.5%. An estimated 300,000 episodes of acute schizophrenia occur annually in the United States, resulting in direct and indirect costs of $62.7 billion.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is principally one of exclusion, requiring the absence of significant associated mood symptoms, any relevant medical condition, and substance abuse. Drug reactions that cause hallucinations, paranoia, confusion, or bizarre behavior may be dose-related or idiosyncratic; parkinsonian medications, clonidine, quinacrine, and procaine derivatives are the most common prescription medications associated with these symptoms. Drug causes should be ruled out in any case of newly emergent psychosis. The general neurologic examination in patients with schizophrenia is usually normal, but motor rigidity, tremor, and dyskinesias are noted in one-quarter of untreated patients.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Epidemiologic surveys identify several risk factors for schizophrenia, including genetic susceptibility, early developmental insults, winter birth, and increasing parental age. Genetic factors are involved in at least a subset of individuals who develop schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is observed in ~6.6% of all first-degree relatives of an affected proband. If both parents are affected, the risk for offspring is 40%. The concordance rate for monozygotic twins is 50%, compared to 10% for dizygotic twins. Schizophrenia-prone families are also at risk for other psychiatric disorders, including schizoaffective disorder and schizotypal and schizoid personality disorders, the latter terms designating individuals who show a lifetime pattern of social and interpersonal deficits characterized by an inability to form close interpersonal relationships, eccentric behavior, and mild perceptual distortions.

ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION OF VIOLENCE

Primary care physicians may encounter situations in which family, domestic, or societal violence is discovered or suspected. Such an awareness can carry legal and moral obligations; many state laws mandate reporting of child, spousal, and elder abuse. Physicians are frequently the first point of contact for both victim and abuser. Approximately 2 million older Americans and 1.5 million U.S. children are thought to experience some form of physical maltreatment each year. Spousal abuse is thought to be even more prevalent. An interview study of 24,000 women in 10 countries found a lifetime prevalence of physical or sexual violence that ranged from 15 to 71%; these individuals are more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, and substance abuse and to have attempted suicide. In addition, abused individuals frequently express low self-esteem, vague somatic symptomatology, social isolation, and a passive feeling of loss of control. Although it is essential to treat these elements in the victim, the first obligation is to ensure that the perpetrator has taken responsibility for preventing any further violence. Substance abuse and/or dependence and serious mental illness in the abuser may contribute to the risk of harm and require direct intervention. Depending on the situation, law enforcement agencies, community resources such as support groups and shelters, and individual and family counseling can be appropriate components of a treatment plan. A safety plan should be formulated with the victim, in addition to providing information about abuse, its likelihood of recurrence, and its tendency to increase in severity and frequency. Antianxiety and antidepressant medications may sometimes be useful in treating the acute symptoms, but only if independent evidence for an appropriate psychiatric diagnosis exists.

MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN THE HOMELESS

There is a high prevalence of mental disorders and substance abuse among homeless and impoverished individuals. Depending on the definition used, estimates of the total number of homeless individuals in the United States range from 800,000 to 2 million, one-third of whom qualify as having a serious mental disorder. Poor hygiene and nutrition, substance abuse, psychiatric illness, physical trauma, and exposure to the elements combine to make the provision of medical care challenging. Only a minority of these individuals receives formal mental health care; the main points of contact are outpatient medical clinics and emergency departments. Primary care settings represent a critical site in which housing needs, treatment of substance dependence, and evaluation and treatment of psychiatric illness can most efficiently take place. Successful intervention is dependent on breaking down traditional administrative barriers to health care and recognizing the physical constraints and emotional costs imposed by homelessness. Simplifying health care instructions and follow-up, allowing frequent visits, and dispensing medications in limited amounts that require ongoing contact are possible techniques for establishing a successful therapeutic relationship.

467 |

Alcohol and Alcoholism |

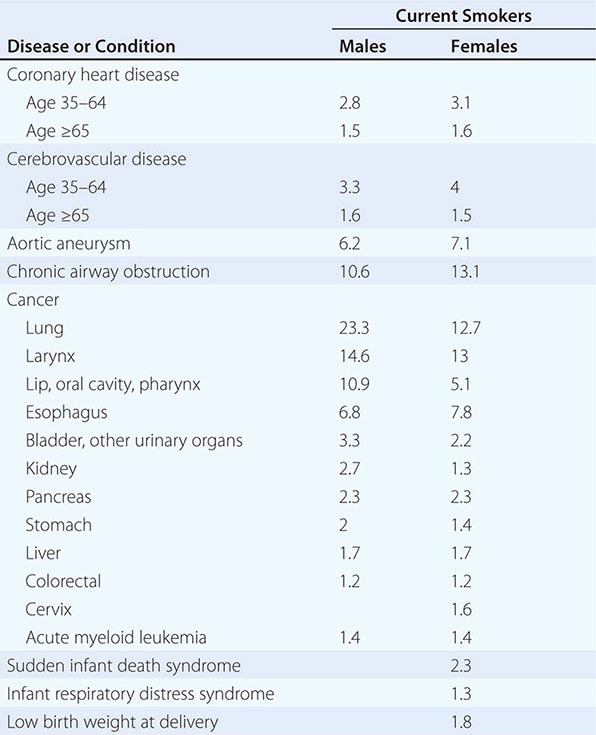

Alcohol (beverage ethanol) distributes throughout the body, affecting almost all systems and altering nearly every neurochemical process in the brain. This drug is likely to exacerbate most medical problems, affect medications metabolized in the liver, and temporarily mimic many medical (e.g., diabetes) and psychiatric (e.g., depression) conditions. The lifetime risk for repetitive alcohol problems is almost 20% for men and 10% for women, regardless of a person’s education or income. Although low doses of alcohol might have healthful benefits, greater than three standard drinks per day enhances the risk for cancer and vascular disease, and alcohol use disorders decrease the life span by about 10 years. Unfortunately, most clinicians have had only limited training regarding alcohol-related disorders. This chapter presents a brief overview of clinically useful information about alcohol use and problems.

PHARMACOLOGY AND NUTRITIONAL IMPACT OF ETHANOL

Ethanol blood levels are expressed as milligrams or grams of ethanol per deciliter (e.g., 100 mg/dL = 0.10 g/dL), with values of ~0.02 g/dL resulting from the ingestion of one typical drink. In round figures, a standard drink is 10–12 g, as seen in 340 mL (12 oz) of beer, 115 mL (4 oz) of nonfortified wine, and 43 mL (1.5 oz) (a shot) of 80-proof beverage (e.g., whisky); 0.5 L (1 pint) of 80-proof beverage contains ~160 g of ethanol (about 16 standard drinks), and 750 mL of wine contains ~60 g of ethanol. These beverages also have additional components (congeners) that affect the drink’s taste and might contribute to adverse effects on the body. Congeners include methanol, butanol, acetaldehyde, histamine, tannins, iron, and lead. Alcohol acutely decreases neuronal activity and has similar behavioral effects and cross-tolerance with other depressants, including benzodiazepines and barbiturates.

Alcohol is absorbed from mucous membranes of the mouth and esophagus (in small amounts), from the stomach and large bowel (in modest amounts), and from the proximal portion of the small intestine (the major site). The rate of absorption is increased by rapid gastric emptying (as seen with carbonation); by the absence of proteins, fats, or carbohydrates (which interfere with absorption); and by dilution to a modest percentage of ethanol (maximum at ~20% by volume).

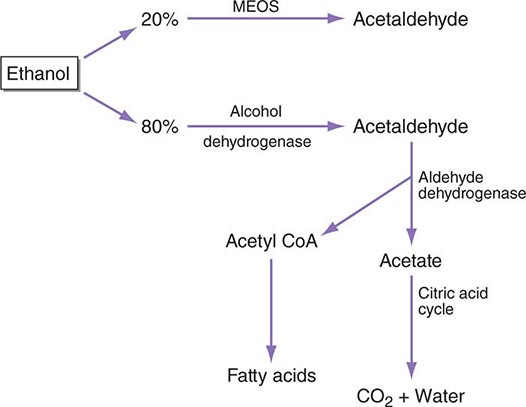

Between 2% (at low blood alcohol concentrations) and 10% (at high blood alcohol concentrations) of ethanol is excreted directly through the lungs, urine, or sweat, but most is metabolized to acetaldehyde, primarily in the liver. The most important pathway occurs in the cell cytosol where alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) produces acetaldehyde, which is then rapidly destroyed by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in the cytosol and mitochondria (Fig. 467-1). A second pathway occurs in the microsomes of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (the microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system, or MEOS) that is responsible for ≥10% of ethanol oxidation at high blood alcohol concentrations.

FIGURE 467-1 The metabolism of alcohol. CoA, coenzyme A; MEOS, microsomal ethanoloxidizing system.

Although a drink contains ~300 kJ, or 70–100 kcal, these are devoid of minerals, proteins, and vitamins. In addition, alcohol interferes with absorption of vitamins in the small intestine and decreases their storage in the liver with modest effects on folate (folacin or folic acid), pyridoxine (B6), thiamine (B1), nicotinic acid (niacin, B3), and vitamin A.

Heavy drinking in a fasting, healthy individual can produce transient hypoglycemia within 6–36 h, secondary to the acute actions of ethanol on gluconeogenesis. This can result in temporary abnormal glucose tolerance tests (with a resulting erroneous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus) until the alcoholic has abstained for 2–4 weeks. Alcohol ketoacidosis, probably reflecting a decrease in fatty acid oxidation coupled with poor diet or recurrent vomiting, can be misdiagnosed as diabetic ketosis. With the former, patients show an increase in serum ketones along with a mild increase in glucose but a large anion gap, a mild to moderate increase in serum lactate, and a β-hydroxybutyrate/lactate ratio of between 2:1 and 9:1 (with normal being 1:1).

In the brain, alcohol affects almost all neurotransmitter systems, with acute effects that are often the opposite of those seen following desistance after a period of heavy drinking. The most prominent actions relate to boosting γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity, especially at GABAA receptors. Enhancement of this complex chloride channel system contributes to anticonvulsant, sleep-inducing, antianxiety, and muscle relaxation effects of all GABA-boosting drugs. Acutely administered alcohol produces a release of GABA, and continued use increases density of GABAA receptors, whereas alcohol withdrawal states are characterized by decreases in GABA-related activity. Equally important is the ability of acute alcohol to inhibit postsynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) excitatory glutamate receptors, whereas chronic drinking and desistance are associated with an upregulation of these excitatory receptor subunits. The relationships between greater GABA and diminished NMDA receptor activity during acute intoxication and diminished GABA with enhanced NMDA actions during alcohol withdrawal explain much of intoxication and withdrawal phenomena.

As with all pleasurable activities, alcohol acutely increases dopamine levels in the ventral tegmentum and related brain regions, and this effect plays an important role in continued alcohol use, craving, and relapse. The changes in dopamine pathways are also linked to increases in “stress hormones,” including cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) during intoxication and withdrawal. Such alterations are likely to contribute to both feelings of reward during intoxication and depression during falling blood alcohol concentrations. Also closely linked to alterations in dopamine (especially in the nucleus accumbens) are alcohol-induced changes in opioid receptors, with acute alcohol causing release of beta endorphins.

Additional neurochemical changes include increases in synaptic levels of serotonin during acute intoxication and subsequent upregulation of serotonin receptors. Acute increases in nicotinic acetylcholine systems contribute to the impact of alcohol in the ventral tegmental region, which occurs in concert with enhanced dopamine activity. In the same regions, alcohol impacts on cannabinol receptors, with resulting release of dopamine, GABA, and glutamate as well as subsequent effects on brain reward circuits.

BEHAVIORAL EFFECTS, TOLERANCE, AND WITHDRAWAL

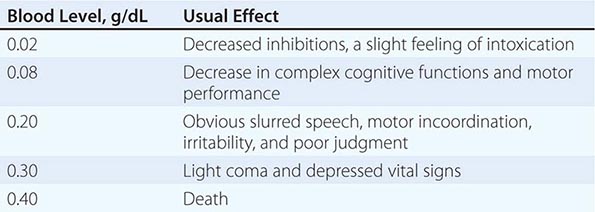

The acute effects of a drug depend on the dose, the rate of increase in plasma, the concomitant presence of other drugs, and past experience with the agent. “Legal intoxication” with alcohol in most states requires a blood alcohol concentration of 0.08 g/dL, but levels of 0.04 are cited in some other countries. However, behavioral, psychomotor, and cognitive changes are seen at 0.02–0.04 g/dL (i.e., after one to two drinks) (Table 467-1). Deep but disturbed sleep can be seen at twice the legal intoxication level, and death can occur with levels between 0.30 and 0.40 g/dL. Beverage alcohol is probably responsible for more overdose deaths than any other drug.

|

EFFECTS OF BLOOD ALCOHOL LEVELS IN THE ABSENCE OF TOLERANCE |

Repeated use of alcohol contributes to acquired tolerance, a phenomenon involving at least three compensatory mechanisms. (1) After 1–2 weeks of daily drinking, metabolic or pharmacokinetic tolerance can be seen, with up to 30% increases in the rate of hepatic ethanol metabolism. This alteration disappears almost as rapidly as it develops. (2) Cellular or pharmacodynamic tolerance develops through neurochemical changes that maintain relatively normal physiologic functioning despite the presence of alcohol. Subsequent decreases in blood levels contribute to symptoms of withdrawal. (3) Individuals learn to adapt their behavior so that they can function better than expected under influence of the drug (learned or behavioral tolerance).

The cellular changes caused by chronic ethanol exposure may not resolve for several weeks or longer following cessation of drinking. Rapid decreases in blood alcohol levels before that time can produce a withdrawal syndrome, which is most intense during the first 5 days, but some symptoms (e.g., disturbed sleep and anxiety) can take up to 4–6 months to resolve.

THE EFFECTS OF ETHANOL ON ORGAN SYSTEMS

Relatively low doses of alcohol (one or two drinks per day) have potential beneficial effects of increasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and decreasing aggregation of platelets, with a resulting decrease in risk for occlusive coronary disease and embolic strokes. Red wine has additional potential health-promoting qualities at relatively low doses due to flavinols and related substances. Modest drinking might also decrease the risk for vascular dementia and, possibly, Alzheimer’s disease. However, any potential healthful effects disappear with the regular consumption of three or more drinks per day, and knowledge about the deleterious effects of alcohol can both help the physician to identify patients with an alcohol use disorder and to supply them with information that might help motivate a change in behavior.

NERVOUS SYSTEM

Approximately 35% of drinkers (and a much higher proportion of alcoholics) experience a blackout, an episode of temporary anterograde amnesia, in which the person forgets all or part of what occurred during a drinking evening. Another common problem, one seen after as few as one or two drinks shortly before bedtime, is disturbed sleep. Although alcohol might initially help a person fall asleep, it disrupts sleep throughout the rest of the night. The stages of sleep are altered, and time spent in rapid eye movement (REM) and deep sleep is reduced. Alcohol relaxes muscles in the pharynx, which can cause snoring and exacerbate sleep apnea; symptoms of the latter occur in 75% of alcoholic men older than age 60 years. Patients may also experience prominent and sometimes disturbing dreams later in the night. All of these sleep problems are more pronounced in alcoholics, and their persistence may contribute to relapse.

Another common consequence of alcohol use is impaired judgment and coordination, increasing the risk of injury. In the United States, ~40% of drinkers have at some time driven while intoxicated. Heavy drinking can also be associated with headache, thirst, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue the following day, a hangover syndrome that is responsible for much missed time and temporary cognitive deficits at work and school.

Chronic high doses cause peripheral neuropathy in ~10% of alcoholics: similar to diabetes, patients experience bilateral limb numbness, tingling, and paresthesias, all of which are more pronounced distally. Approximately 1% of alcoholics develop cerebellar degeneration or atrophy, producing a syndrome of progressive unsteady stance and gait often accompanied by mild nystagmus; neuroimaging studies reveal atrophy of the cerebellar vermis. Fortunately, very few alcoholics (perhaps as few as 1 in 500 for the full syndrome) develop Wernicke’s (ophthalmoparesis, ataxia, and encephalopathy) and Korsakoff’s (retrograde and anterograde amnesia) syndromes, although a higher proportion have one or more neuropathologic findings related to these conditions. These result from low levels of thiamine, especially in predisposed individuals with transketolase deficiencies. Alcoholics can manifest cognitive problems and temporary memory impairment lasting for weeks to months after drinking heavily for days or weeks. Brain atrophy, evident as ventricular enlargement and widened cortical sulci on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans, occurs in ~50% of chronic alcoholics; these changes are usually reversible if abstinence is maintained. There is no single alcoholic dementia syndrome; rather, this label describes patients who have irreversible cognitive changes (possibly from diverse causes) in the context of chronic alcoholism.

Psychiatric Comorbidity As many as two-thirds of individuals with alcohol use disorders meet the criteria for another psychiatric syndrome in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) of the American Psychiatric Association (Chap. 466). Half of these relate to a preexisting antisocial personality manifesting as impulsivity and disinhibition that contribute to both alcohol and drug use disorders. The lifetime risk is 3% in males, and ≥80% of such individuals demonstrate alcohol- and/or drug-related conditions. Another common comorbidity occurs with problems regarding illicit substances. The remainder of alcoholics with psychiatric syndromes have preexisting conditions such as schizophrenia or manic-depressive disease and anxiety syndromes such as panic disorder. The comorbidities of alcoholism with independent psychiatric disorders might represent an overlap in genetic vulnerabilities, impaired judgment in the use of alcohol from the independent psychiatric condition, or an attempt to use alcohol to alleviate symptoms of the disorder or side effects of medications.

Many psychiatric syndromes can be seen temporarily during heavy drinking and subsequent withdrawal. These alcohol-induced conditions include an intense sadness lasting for days to weeks in the midst of heavy drinking seen in 40% of alcoholics, which tends to disappear over several weeks of abstinence (alcohol-induced mood disorder); temporary severe anxiety in 10–30% of alcoholics, often beginning during alcohol withdrawal, which can persist for a month or more after cessation of drinking (alcohol-induced anxiety disorder); and auditory hallucinations and/or paranoid delusions in a person who is alert and oriented, seen in 3–5% of alcoholics (alcohol-induced psychotic disorder).

Treatment of all forms of alcohol-induced psychopathology includes helping patients achieve abstinence and offering supportive care, as well as reassurance and “talk therapy” such as cognitive-behavioral approaches. However, with the exception of short-term antipsychotics or similar drugs for substance-induced psychoses, substance-induced psychiatric conditions only rarely require medications. Recovery is likely within several days to 4 weeks of abstinence. Conversely, because alcohol-induced conditions are temporary and do not indicate a need for long-term pharmacotherapy, a history of alcohol intake is an important part of the workup for any patient with one of these psychiatric symptoms.

THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

Esophagus and Stomach Alcohol can cause inflammation of the esophagus and stomach causing epigastric distress and gastrointestinal bleeding, making alcohol one of the most common causes of hemorrhagic gastritis. Violent vomiting can produce severe bleeding through a Mallory-Weiss lesion, a longitudinal tear in the mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

Pancreas and Liver The incidence of acute pancreatitis (~25 per 1000 per year) is almost threefold higher in alcoholics than in the general population, accounting for an estimated 10% or more of the total cases. Alcohol impairs gluconeogenesis in the liver, resulting in a fall in the amount of glucose produced from glycogen, increased lactate production, and decreased oxidation of fatty acids. This contributes to an increase in fat accumulation in liver cells. In healthy individuals these changes are reversible, but with repeated exposure to ethanol, especially daily heavy drinking, more severe changes in the liver occur, including alcohol-induced hepatitis, perivenular sclerosis, and cirrhosis, with the latter observed in an estimated 15% of alcoholics (Chap. 363). Perhaps through an enhanced vulnerability to infections, alcoholics have an elevated rate of hepatitis C, and drinking in the context of that disease is associated with more severe liver deterioration.

CANCER

As few as 1.5 drinks per day increases a woman’s risk of breast cancer 1.4-fold. For both genders, four drinks per day increases the risk for oral and esophageal cancers approximately threefold and rectal cancers by a factor of 1.5; seven to eight or more drinks per day produces an approximately fivefold increased risk for many cancers. These consequences may result directly from cancer-promoting effects of alcohol and acetaldehyde or indirectly by interfering with immune homeostasis.

HEMATOPOIETIC SYSTEM

Ethanol causes an increase in red blood cell size (mean corpuscular volume [MCV]), which reflects its effects on stem cells. If heavy drinking is accompanied by folic acid deficiency, there can also be hypersegmented neutrophils, reticulocytopenia, and a hyperplastic bone marrow; if malnutrition is present, sideroblastic changes can be observed. Chronic heavy drinking can decrease production of white blood cells, decrease granulocyte mobility and adherence, and impair delayed-hypersensitivity responses to novel antigens (with a possible false-negative tuberculin skin test). Associated immune deficiencies can contribute to vulnerability toward infections, including hepatitis and HIV, and interfere with their treatment. Finally, many alcoholics have mild thrombocytopenia, which usually resolves within a week of abstinence unless there is hepatic cirrhosis or congestive splenomegaly.

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

Acutely, ethanol decreases myocardial contractility and causes peripheral vasodilation, with a resulting mild decrease in blood pressure and a compensatory increase in cardiac output. Exercise-induced increases in cardiac oxygen consumption are higher after alcohol intake. These acute effects have little clinical significance for the average healthy drinker but can be problematic when persisting cardiac disease is present.

The consumption of three or more drinks per day results in a dose-dependent increase in blood pressure, which returns to normal within weeks of abstinence. Thus, heavy drinking is an important factor in mild to moderate hypertension. Chronic heavy drinkers also have a sixfold increased risk for coronary artery disease, related, in part, to increased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and carry an increased risk for cardiomyopathy through direct effects of alcohol on heart muscle. Symptoms of the latter include unexplained arrhythmias in the presence of left ventricular impairment, heart failure, hypocontractility of heart muscle, and dilation of all four heart chambers with associated mural thrombi and mitral valve regurgitation. Atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, especially paroxysmal tachycardia, can also occur temporarily after heavy drinking in individuals showing no other evidence of heart disease—a syndrome known as the “holiday heart.”

GENITOURINARY SYSTEM CHANGES, SEXUAL FUNCTIONING, AND FETAL DEVELOPMENT

Drinking in adolescence can affect normal sexual development and reproductive onset. At any age, modest ethanol doses (e.g., blood alcohol concentrations of 0.06 g/dL) can increase sexual drive but also decrease erectile capacity in men. Even in the absence of liver impairment, a significant minority of chronic alcoholic men show irreversible testicular atrophy with shrinkage of the seminiferous tubules, decreases in ejaculate volume, and a lower sperm count (Chap. 411).

The repeated ingestion of high doses of ethanol by women can result in amenorrhea, a decrease in ovarian size, absence of corpora lutea with associated infertility, and an increased risk of spontaneous abortion. Heavy drinking during pregnancy results in the rapid placental transfer of both ethanol and acetaldehyde, which may contribute to a range of consequences known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). One severe result is the fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), seen in ~5% of children born to heavy-drinking mothers, which can include any of the following: facial changes with epicanthal eye folds; poorly formed ear concha; small teeth with faulty enamel; cardiac atrial or ventricular septal defects; an aberrant palmar crease and limitation in joint movement; and microcephaly with mental retardation. Less pervasive FASD conditions include combinations of low birth weight, a lower intelligence quotient (IQ), hyperactive behavior, and some modest cognitive deficits. The amount of ethanol required and the time of vulnerability during pregnancy have not been defined, making it advisable for pregnant women to abstain completely.

OTHER EFFECTS

Between one-half and two-thirds of alcoholics have skeletal muscle weakness caused by acute alcoholic myopathy, a condition that improves but which might not fully remit with abstinence. Effects of repeated heavy drinking on the skeletal system include changes in calcium metabolism, lower bone density, and decreased growth in the epiphyses, leading to an increased risk for fractures and osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Hormonal changes include an increase in cortisol levels, which can remain elevated during heavy drinking; inhibition of vasopressin secretion at rising blood alcohol concentrations and enhanced secretion at falling blood alcohol concentrations (with the final result that most alcoholics are likely to be slightly overhydrated); a modest and reversible decrease in serum thyroxine (T4); and a more marked decrease in serum triiodothyronine (T3). Hormone irregularities should be reevaluated because they may disappear after a month of abstinence.

ALCOHOLISM (ALCOHOL USE DISORDER)

Because many drinkers occasionally imbibe to excess, temporary alcohol-related problems are common in nonalcoholics, especially in the late teens to the late twenties. However, repeated problems in multiple life areas can indicate an alcohol use disorder as defined in DSM-5.

DEFINITIONS AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

An alcohol use disorder is defined as repeated alcohol-related difficulties in at least 2 of 11 life areas that cluster together in the same 12-month period (Table 467-2). Ten of the 11 items were taken directly from the 7 dependence and 4 abuse criteria in DSM-IV, after deleting legal problems and adding craving. Severity of an alcohol use disorder is based on the number of items endorsed: mild is two or three items; moderate is four or five; and severe is six or more of the criterion items. The new diagnostic approach is similar enough to DSM-IV that the following descriptions of associated phenomena are still accurate.

|

DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL OF MENTAL DISORDERS, FIFTH EDITION, CLASSIFICATION OF ALCOHOL USE DISORDER (AUD) |

aMild AUD: 2–3 criteria required; Moderate AUD: 4–5 items endorsed; severe AUD: 6 or more items endorsed.

The lifetime risk for an alcohol use disorder in most Western countries is about 10–15% for men and 5–8% for women. Rates are similar in the United States, Canada, Germany, Australia, and the United Kingdom, tend to be lower in most Mediterranean countries, such as Italy, Greece, and Israel, and may be higher in Ireland, France, and Scandinavia. An even higher lifetime prevalence has been reported for most native cultures, including American Indians, Eskimos, Maori groups, and aboriginal tribes of Australia. These differences reflect both cultural and genetic influences, as described below. In Western countries, the typical alcoholic is more often a blue- or white-collar worker or homemaker. The lifetime risk for alcoholism among physicians is similar to that of the general population.

GENETICS

Approximately 60% of the risk for alcohol use disorders is attributed to genes, as indicated by the fourfold higher risk in children of alcoholics (even if adopted early in life and raised by nonalcoholics) and a higher risk in identical twins compared to fraternal twins of alcoholics. The genetic variations operate primarily through intermediate characteristics that subsequently combine with environmental influences to alter the risk for heavy drinking and alcohol problems. These include genes relating to a high risk for all substance use disorders that operate through impulsivity, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Another characteristic, an intense flushing response when drinking, decreases the risk for only alcohol use disorders through gene variations for several alcohol-metabolizing enzymes, especially aldehyde dehydrogenase (a mutation only seen in Asians), and to a lesser extent, variations in ADH.

An additional genetically influenced characteristic, a low sensitivity to alcohol, affects the risk for heavy drinking and may operate, in part, through variations in genes relating to calcium and potassium channels, GABA, nicotinic, and serotonin systems. A low response per drink is observed early in the drinking career and before alcohol use disorders develop. All follow-up studies have demonstrated that this need for higher doses of alcohol to achieve effects predicts future heavy drinking, alcohol problems, and alcohol use disorders. The impact of a low response to alcohol on adverse drinking outcomes is partially mediated by a range of environmental influences, including the selection of heavier-drinking friends, more positive expectations of the effects of high doses of alcohol, and suboptimal ways of coping with stress.

NATURAL HISTORY

Although the age of the first drink (~15 years) is similar in most alcoholics and nonalcoholics, a slightly earlier onset of regular drinking and drunkenness, especially in the context of conduct problems, is associated with a higher risk for later alcohol use disorders. By the mid-twenties, most nonalcoholic men and women moderate their drinking (perhaps learning from problems), whereas alcoholics are likely to escalate their patterns of drinking despite difficulties. The first major life problem from alcohol often appears in the late teens to early twenties, and a pattern of multiple alcohol difficulties by the midtwenties. Once established, the course of alcoholism is likely to include exacerbations and remissions, with little difficulty in temporarily stopping or controlling alcohol use when problems develop, but without help, desistance usually gives way to escalations in alcohol intake and subsequent problems. Following treatment, between half and two-thirds of alcoholics maintain abstinence for years, and often permanently. Even without formal treatment or self-help groups, there is at least a 20% chance of spontaneous remission with long-term abstinence. However, should the alcoholic continue to drink heavily, the life span is shortened by ~10 years on average, with the leading causes of death being heart disease, cancer, accidents, and suicide.

TREATMENT

The approach to treating alcohol-related conditions is relatively straightforward: (1) recognize that at least 20% of all patients have an alcohol use disorder; (2) learn how to identify and treat acute alcohol-related conditions; (3) know how to help patients begin to address their alcohol problems; and (4) know enough about treating alcoholism to appropriately refer patients for additional help.

IDENTIFICATION OF THE ALCOHOLIC

Even in affluent locales, ~20% of patients have an alcohol use disorder. These men and women can be identified by asking questions about alcohol problems and noting laboratory test results that can reflect regular consumption of six to eight or more drinks per day. The two blood tests with ≥60% sensitivity and specificity for heavy alcohol consumption are γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) (>35 U) and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) (>20 U/L or >2.6%); the combination of the two is likely to be more accurate than either alone. The values for these serologic markers are likely to return toward normal within several weeks of abstinence. Other useful blood tests include high-normal MCVs (≥91 μm3) and serum uric acid (>416 mol/L, or 7 mg/dL).

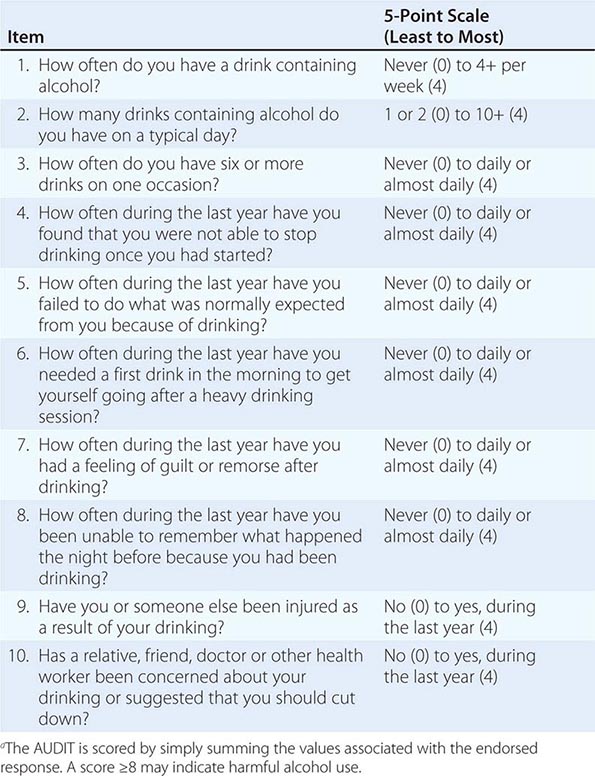

The diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder ultimately rests on the documentation of a pattern of repeated difficulties associated with alcohol (Table 467-2). Thus, in screening, it is important to probe for marital or job problems, legal difficulties, histories of accidents, medical problems, evidence of tolerance, and so on, and then attempt to tie in use of alcohol or another substance. Some standardized questionnaires can be helpful, including the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Table 467-3), but these are only screening tools, and a face-to-face interview is still required for a meaningful diagnosis.

|

THE ALCOHOL USE DISORDERS IDENTIFICATION TEST (AUDIT)a |

GLOBAL CONSIDERATIONS

![]() As described above, rates of alcohol use disorders differ across sex, age, ethnicity, and country. There are also differences across countries regarding the definition of a standard drink (e.g., 10–12 g of ethanol in the United States and 8 g in the United Kingdom) and the definition of being legally drunk. The preferred alcoholic beverage also varies across groups, even within countries. That said, regardless of sex, ethnicity, or country, the actual drug in the drink is still ethanol, and the risks for problems, course of alcohol use disorders, and approaches to treatment are similar across the world.

As described above, rates of alcohol use disorders differ across sex, age, ethnicity, and country. There are also differences across countries regarding the definition of a standard drink (e.g., 10–12 g of ethanol in the United States and 8 g in the United Kingdom) and the definition of being legally drunk. The preferred alcoholic beverage also varies across groups, even within countries. That said, regardless of sex, ethnicity, or country, the actual drug in the drink is still ethanol, and the risks for problems, course of alcohol use disorders, and approaches to treatment are similar across the world.

468e |

Opioid-Related Disorders |

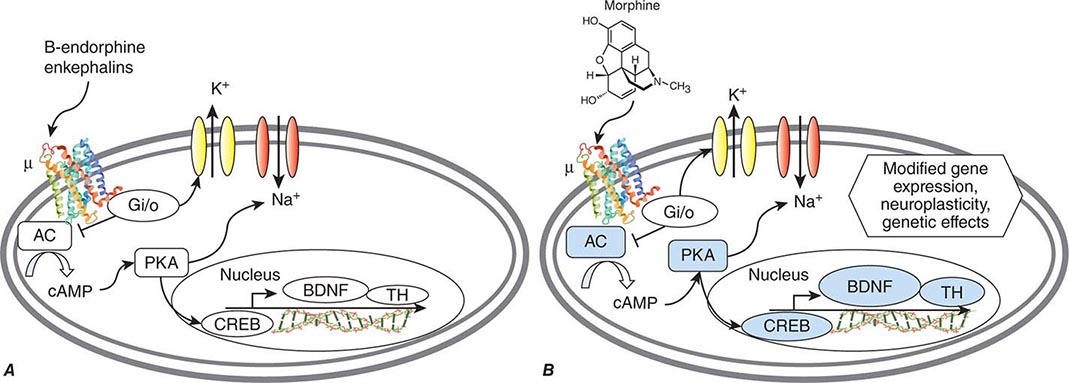

![]() Opiate analgesics have been abused since at least 300 B.C. Nepenthe (Greek “free from sorrow”) helped the hero of the Odyssey, but widespread opium smoking in China and the Near East has caused harm for centuries. Since the first chemical isolation of opium and codeine 200 years ago, a wide range of synthetic opioids have been developed, and opioid receptors were cloned in the 1990s. Two of the most important adverse effects of all these agents are the development of opioid use disorder and overdose. The 0.1% annual prevalence of heroin dependence in the United States is only about one-third the rate of prescription opiate use and is substantially lower than the 2% rate of morphine users in Southeast and Southwest Asia. Prescription opiates are primarily used for pain management, but due to ease of availability, adolescents procure and use these drugs with dire consequences. In 2011, for example, 11 million individuals in the United States used nonmedically prescribed pain killers that were linked to over 420,000 emergency department visits and nearly 17,000 overdose deaths. Although these rates are low relative to other abused substances, their disease burden is substantial, with high rates of morbidity and mortality; disease transmission; increased health care, crime, and law enforcement costs; and less tangible costs of family distress and lost productivity.