27 Coarctation of aorta

Salient features

History

• Symptoms are usually those of hypertension: headache, epistaxis, dizziness, and palpitations

• Claudication (caused by diminished blood flow the legs)

• Occasionally, diminished blood

• Patients sometimes seek medical attention because they have symptoms of heart failure or aortic dissection. Women with coarctation are at particularly high risk for aortic dissection during pregnancy.

Examination

• The upper torso is better developed than the lower part (as the lower body has chronic low systolic blood pressure compared to the upper part).

• The systolic arterial pressure is higher in the arms than in the legs, but the diastolic pressures are similar; therefore, a widened pulse pressure is present in the arms. (Note: This condition results in hypertension in the arms. Less commonly, the coarctation is immediately proximal to the left subclavian artery, in which case a difference in arterial pressure is noted between the arms.)

• Radial pulse on the left side may be less prominent.

• The femoral arterial pulses are weak and delayed (simultaneous palpation of the brachial and femoral arteries using the thumbs is the most convenient method of comparing pulsations in the upper and lower limbs).

• A systolic thrill may be palpable in the suprasternal notch.

• Heaving apex caused by left ventricular enlargement.

• A systolic ejection click (caused by a bicuspid aortic valve which occurs in 50% of cases) is frequently present, and the second heart sound is accentuated.

• A harsh systolic ejection murmur may be identified along the left sternal border and in the back, particularly over the coarctation.

• Scapular collaterals are visible (listen over these collaterals for murmur).

• A systolic murmur, caused by flow through collateral vessels, may be heard in the back.

• In about 30% of patients with aortic coarctation, a systolic murmur indicating an associated bicuspid aortic valve is audible at the base.

Advanced-level questions

What are the types of aortic coarctation?

Common

• Infantile or preductal where the aorta between the left subclavian artery and patent ductus arteriosus is narrowed. It manifests in infancy with heart failure. Associated lesions include patent ductus arteriosus, aortic arch anomalies, transposition of the great arteries, ventricular septal defect.

• Adult type: the coarctation in the descending aorta is juxtaductal or slightly postductal. It may be associated with biscuspid aortic valve or patent ductus arteriosus. It commonly presents between the ages of 15 and 30 years.

Rare

• Localized juxtaductal coarctation

• Coarctation of the ascending thoracic aorta

• Coarctation of the distal descending thoracic aorta

• Coarctation of the abdominal aorta

• Pseudocoarctation is of no haemodynamic significance and is a ‘kinked’ appearance of the aorta in the juxtaductal region without stenosis.

Is aortic coarctation commoner in men or women?

This condition is two to five times as frequent in men and boys as in women and girls.

How would you investigate this patient?

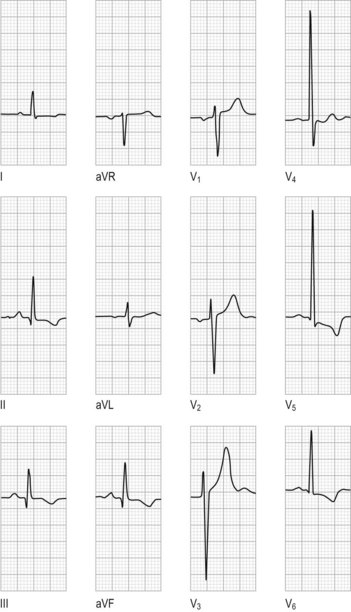

• Electrocardiogram usually shows left ventricular hypertrophy (Fig. 27.1).

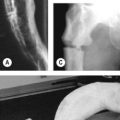

• Chest radiograph shows symmetric rib notching. The coarctation may be visualized as the characteristic ‘3’ sign on a chest radiograph (Fig. 27.2). The upper bulge is formed by dilatation of the left subclavian artery high on the left mediastinal border; the sharp indentation is the site of the coarctation and the lower bulge is called the poststenotic dilatation of the aorta.

• Echocardiography may visualize the coarctation; Doppler examination makes possible an estimate of the transcoarctation pressure gradient.

• Computed tomography (CT), MRI and contrast aortography are useful to determine the precise anatomy regarding the location and length of the coarctation; in addition, aortography permits the visualization of the collateral circulation.

What do you understand by the term pseudocoarctation?

It refers to buckling or kinking of the aortic arch without the presence of a significant gradient.

What are the complications of aortic coarctation?

• Severe hypertension and resulting complications:

• Infective endocarditis endarteritis (at the site of the coarctation or on a congenitally bicuspid aortic valve).

• Intracranial haemorrhage (combination of hypertension and ruptured berry aneurysm).

• Death occurs in 75% by the age of 50, and 90% by the age of 60 (Br Heart J 1970;32:633–40).

What are the fundal findings in coarctation of aorta?

Hypertension caused by coarctation of aorta causes retinal arteries to be tortuous with frequent ‘U’ turns; curiously, the classical signs of hypertensive retinopathy are rarely seen (see Fig. 202.1).

What is the treatment of such patients?

• Balloon dilatation with stent insertion in patients with native coarctation and recoarctation can be done with good immediate and medium-term results in adolescents and adults and should probably be the procedure of choice when the anatomy is suitable and expert skills are available.

• When the anatomy is not suitable (i.e. long tunnel-like stenosis) surgical resection and end-to-end anastomosis may be needed, although a tubular graft may be required if the narrowed segment is too long. After surgical repair of isolated aortic coarctation, the obstruction is usually relieved with minimum mortality (<2%). However, mortality is increased for reoperation (5–15%).

What happens to the hypertension after surgery?

• Among patients who undergo surgery during childhood, 90% are normotensive 5 years later, 50% are normotensive 20 years later, and 25% are normotensive 25 years later.

• Among those who undergo surgery after the age of 40 years, half have persistent hypertension, and many of those with a normal resting BP after successful repair have a hypertensive response to exercise.