CNS neoplasia I

Intracranial tumours

In adults, primary intracranial tumours represent only 3% of tumour-related deaths, and have an annual incidence of 4–7 per 100 000. Intracranial metastases are more common. Intracranial tumours are the second most common tumour in childhood with an annual incidence of 2–3 per 100 000.

Pathology

Intracranial tumours can be divided into intrinsic and extrinsic (Table 1).

Table 1 Approximate frequency of different intracranial tumours

| Tumour | Percentage of total | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | ||

| Glioblastoma multiforme | 20 | High-grade glioma; poor prognosis |

| Astrocytoma | 10 (48 in children) | Lower-grade glioma |

| Metastases | 10* | Often multiple |

| Oligodendroglioma | 5 | Slow growing. Often frontal or temporal and calcifies |

| Ependymoma† | 5 (10 in children) | Arise from ependymal lining, usually of 4th ventricle |

| Medulloblastoma† | 5 (45 in children) | Arise from cerebellum. May metastasize within CNS |

| Primary CNS lymphoma | Rare except in AIDS | May be multifocal |

| Extrinsic | ||

| Meningioma† | 15 | Arise from meninges and indent brain, may erode bone |

| Pituitary adenoma† | 7 | Chiasmatic visual disturbance and endocrine effects |

| Schwannoma, e.g. of acoustic nerve† | 7 | Benign |

| Other | 16 | Includes teratomas, pinealomas, etc. |

Estimates are taken from a combination of series

* Metastases are much more common. This estimate is of those with solitary intracranial metastases

Aetiology

The aetiology of most brain tumours is unknown. Hypotheses include the pathological activation of embryonic cell rests, for example in primitive tumours such as teratomas, or the dedifferentiation of mature cells to more primitive cells and neoplastic transformation. The importance of genetic changes is supported by the large number of inherited syndromes of CNS tumours, for example neurofibromatosis (p. 97). There are changes at specific sites of the genome in many tumours, including chromosome 22 loss in up to 70% of meningiomas, P53 gene (involved in DNA repair) in up to 40% of astrocytomas and epidermal growth factor receptor gene amplification in up to 40% of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). These changes represent an exciting development in understanding but their exact role is unclear; because none is seen in 100% of the appropriate tumour type, other factors must also be important. Endocrine factors are important in some tumours; meningiomas are more common in females, grow more rapidly in pregnancy and may express oestrogen receptors.

Clinical features

Management of intracranial tumours

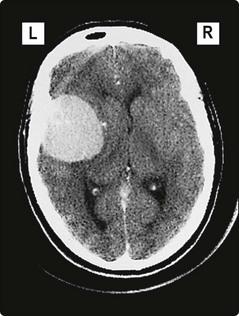

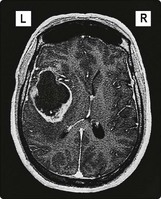

Treatment differs depending on the clinical situation, site of the tumour, the eloquence of the related part of the brain and the type of tumour. The objective of treatment will vary, from curative resection of a meningioma (Fig. 1) to palliation in a glioma (Fig. 2). Some rarer tumours have different treatment objectives (p. 96).

Presurgical management

Seizures are treated as focal epilepsy (p. 76). In the emergency situation, a loading dose of intravenous phenytoin is often used.