8.7 CNS infections

meningitis and encephalitis

Meningitis

Aetiology

Bacteria

In Australia, meningococcal disease, particularly that caused by serogroup C, has declined since introduction of the meningococcal C conjugate vaccine (MenCCV) into the National Immunisation Program (NIP) schedule. The most common N. meningitidis serogroup causing invasive disease in those under 19 years is serogroup B (91%), followed by serogroup C (2–3%).1 Until the introduction of 7-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (7vPCV) into the NIP schedule, the most common pneumococcal serotypes causing invasive disease were those contained in 7vPCV (14, 6B, 18C, 19F, 4, 23F, 9V).2 However, since then, it appears that serotype replacement is occurring; nasal carriage of 7PCV serotypes has been replaced by others, namely 19A and 16F,3 and the rate of invasive pneumococcal disease caused by 7vPCV serotypes has decreased significantly.4 However, the rate of invasive pneumococcal disease caused by serotype 19A increased in non-Indigenous people and in the population overall.4 Antibiotic resistance is almost exclusively restricted to these serotypes (and remaining 7PCV serotypes).

Clinical findings

The classical features of meningitis comprise fever, headache, vomiting, neck stiffness, photophobia and altered mentation. However, the clinical manifestations are often non-specific, particularly in infants and young children. They may include fever, irritability, lethargy, poor feeding or vomiting. Up to 58% of children with meningitis have received antibiotics before the emergency department (ED) presentation.5 This may modify the clinical presentation of meningitis.6 It is therefore important to consider the possibility of central nervous system (CNS) infection in any sick infant or child, particularly if they are already taking antibiotics.

If the fontanelle is still open, it may be bulging when examined with the infant in a sitting position. Photophobia is difficult to ascertain in young children, and other signs of meningeal irritation may be absent or difficult to elicit. Resistance to being picked up or distress on walking may be the only clues. Kernig’s sign (inability to extend the knee when the leg is flexed at the hip), Brudzinski’s sign (bending the head forward produces flexion movements of the legs) and nuchal rigidity may be present in older children, but have even been shown to have low positive and negative predictive value in adults with meningitis.7

Investigations

A bulging fontanelle, in the absence of other signs of raised ICP, is not a contraindication to LP.

Cerebral computerised tomography (CT) should not be used to decide whether it is safe to proceed with LP or not. In a prospective study of bacterial meningitis, CT findings obtained during the acute stages failed to reveal any clinically significant abnormalities that were not suspected on neurological examination.8 Moreover, cerebral herniation can occur with a normal CT9,10 and the true cause of coning and relationship to prior lumbar puncture is not clearly established.

Other relative contraindications to LP include:

Examination of the CSF

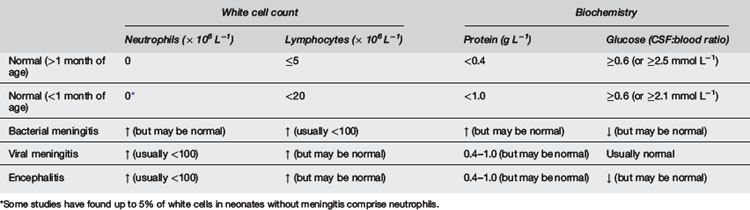

A CSF specimen should always be sent for urgent microscopy to help guide empiric treatment. Normal CSF is clear and contains few cells (and no neutrophils). As few as 200 × 106 cells per litre will cause CSF to appear turbid. The CSF profile may help differentiate between bacterial and viral meningitis, but the findings vary. Table 8.7.1 indicates the typical profiles in normal children and those with meningitis. However, these should always be interpreted in the context of the clinical picture. In early bacterial meningitis, the CSF cell count may be normal. In enteroviral meningitis, there is typically a neutrophil predominance early, and this may remain so for more than 24 hours.11

A traumatic tap occurs in 15–20% of LP in children.12,13 Several formulae have been devised for interpretation of CSF contaminated with blood, but the safest practice is to disregard the red cell count and treat if meningitis is suspected until culture and other studies are clearly negative.

Seizures do not result in increased CSF cell count in the absence of meningitis.

Other investigations

Management

Antibiotics

Following initial fluid resuscitation, the emphasis is on prompt commencement of parenteral antibiotics. Delay in antibiotic therapy has been associated with adverse clinical outcome in adults with bacterial meningitis.14

Rates of resistance to penicillin and cephalosporins amongst pneumococci have fallen in Australia since the introduction of the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine.3,4,15 Vancomycin should be added if rates of resistance are high.

Steroids

Routine administration of steroids as adjunctive therapy has been controversial in the past. The evidence that they protect against neurological (particularly audiological) complications of childhood meningitis is strongest for Hib meningitis, when dexamethasone is given before the first dose of antibiotics, and when a third generation cephalosporin is used. A recent large European trial in adults with meningitis showed reduction in mortality and severe morbidity with pneumococcal meningitis.16 A recent Cochrane meta-analysis including adult and paediatric trials concluded that adjuvant steroids are beneficial for children with bacterial meningitis.17 Evidence from animal studies shows that dexamethasone reduces penetration of vancomycin into infected cerebrospinal fluid.18 Thus, there is concern that use of dexamethasone with vancomycin could compromise the efficacy of vancomycin in third generation cephalosporin-resistant strains. Fortunately, the majority of cases of pneumococcal meningitis are still caused by strains that are susceptible to penicillin and third-generation cephalosporins.

Fluids

Careful management of fluid and electrolyte balance is important in the treatment of meningitis. Over or under hydration are associated with adverse outcomes.19–21 Many children have increased antidiuretic hormone secretion, and some will have dehydration due to vomiting, poor fluid intake or septic shock. Assessment of the clinical signs of hydration, including weight, measurement of the serum sodium, documentation of urine output, and clinical assessment of the neurological state should be monitored closely, and the total fluid intake adjusted accordingly.

Initial fluid resuscitation to treat shock should be with 20 mL kg−1 of isotonic (normal) saline. Thereafter, isotonic fluids should be given to maintain systemic blood pressure (and thereby cerebral blood flow). Previous guidelines have emphasised the importance of fluid restriction.19 It may be necessary to restrict fluids if the serum sodium is <130 mmol L−1, or if there are signs of fluid overload. However, fluid restriction does not generally improve outcome20 and has even been associated with a worse neurological outcome.21 Thus, most children should receive normal maintenance fluid volumes.

Prevention

Complications

Bacterial meningitis is associated with a 4.5% mortality rate, and intellectual, cognitive and auditory impairment in 10–20% of survivors.22 The risk for sequelae is greatest in those who experience acute neurological complications at the time of their illness.23

Encephalitis

Investigations

CSF biochemistry and microscopy findings are non-specific (see Table 8.7.1). PCR testing for HSV and enterovirus is sensitive and specific. Cerebral CT or MRI of the brain and EEG may be suggestive of HSV encephalitis, particularly if they show temporal lobe involvement.

Management

1 Annual report of the Australian Meningococcal Surveillance Programme, 2008. Commun Dis Intell. 2009;33(3):259-267.

2 Liu M., Andrews R., Stylianopoulos J., et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among children in Victoria. Commun Dis Intell. 2003;27(3):362-366.

3 Leach A., Morris P., McCallum G., et al. Emerging pneumococcal carriage serotypes in a high-risk population receiving universal 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine since 2001. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:121-129.

4 Giele C., Anthony K., Lehmann D., Van Buynder P. Invasive pneumococcal disease in Western Australia: emergence of serotype 19A. Med J Aust. 2009;190:166.

5 Kallio M.J., Kilpi T., Anttila M., Peltola H. The effect of a recent previous visit to a physician on outcome after childhood bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 1994;272(10):787-791.

6 Rothrock S.G., Green S.M., Wren J., et al. Pediatric bacterial meningitis: is prior antibiotic therapy associated with an altered clinical presentation? Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(2):146-152.

7 Thomas K.E., Hasbun R., Jekel J., Quagliarello V.J. The diagnostic accuracy of Kernig’s sign, Brudzinski’s sign, and nuchal rigidity in adults with suspected meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(1):46-52.

8 Cabral D.A., Flodmark O., Farrell K., Speert D.P. Prospective study of computed tomography in acute bacterial meningitis. J Pediatr. 1987;111(2):201-205.

9 Rennick G., Shann F., de Campo J. Cerebral herniation during bacterial meningitis in children. Br Med J. 1993;306(6883):953-955.

10 Shetty A.K., Desselle B.C., Craver R.D., Steele R.W. Fatal cerebral herniation after lumbar puncture in a patient with a normal computed tomography scan. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6):1284-1286.

11 Negrini B., Kelleher K.J., Wald E.R. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in aseptic versus bacterial meningitis. Pediatrics. 2000;105(2):316-319.

12 Mazor S.S., McNulty J.E., Roosevelt G.E. Interpretation of traumatic lumbar punctures: who can go home? Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):525-528.

13 Shah K.H., Richard K.M., Nicholas S., Edlow J.A. Incidence of traumatic lumbar puncture. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(2):151-154.

14 Aronin S.I., Peduzzi P., Quagliarello V.J. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis: risk stratification for adverse clinical outcome and effect of antibiotic timing. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(11_Part_1):862-869.

15 McMaster P., McIntyre P., Gilmour R., et al. The emergence of resistant pneumococcal meningitis – implications for empiric therapy. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87(3):207-210.

16 de Gans J., van de Beek D., the European Dexamethasone in Adulthood Bacterial Meningitis Study Investigators. Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1549-1556.

17 Brouwer M., McIntyre P., de Gans J., et al. Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (9):2010. CD004405

18 Martinez-Lacasa J., Cabellos C., Martos A., et al. Experimental study of the efficacy of vancomycin, rifampicin and dexamethasone in the therapy of pneumococcal meningitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49(3):507-513.

19 Shann F., Germer S. Hyponatraemia associated with pneumonia or bacterial meningitis. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60(10):963-966.

20 Duke T., Mokela D., Frank D., et al. Management of meningitis in children with oral fluid restriction or intravenous fluid at maintenance volumes: a randomised trial. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2002;22(2):145-157.

21 Singhi S.C., Singhi P.D., Srinivas B., et al. Fluid restriction does not improve the outcome of acute meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14(6):495-503.

22 Baraff L.J., Lee S.I., Schriger D.L. Outcomes of bacterial meningitis in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12(5):389-394.

23 Grimwood K., Anderson P., Anderson V., et al. Twelve year outcomes following bacterial meningitis: further evidence for persisting effects. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83(2):111-116.

24 Whitley R.J., Lakeman F. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: therapeutic and diagnostic considerations. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(2):414-420.