146 Clostridium difficile Colitis

Antibiotic-associated colitis was recognized soon after antibiotics were introduced in the 1940s, but the cause was not known until 1978 with the original reports of the role of Clostridium difficile as the putative agent in nearly all cases of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis and 10% to 15% of those with uncomplicated antibiotic-associated diarrhea.1 Subsequent work has identified the pathophysiology, epidemiology, diagnostic methods, and treatment for this condition. The major challenges continue to be prevention and the management of patients with advanced disease, particularly those with ileus.

Etiology

Etiology

C. difficile causes a spectrum of enteric complications of antibiotic use ranging from nuisance diarrhea to severe and sometimes life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis. There are occasional cases of antibiotic-associated colitis due to other pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella oxytoca, enterotoxin-producing strains of Clostridium perfringens or Salmonella), but most cases are either due to C. difficile or are enigmatic.2

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

There are six relevant issues:

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

The typical presentation of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is watery diarrhea associated with cramps.2 Other common features are fecal leukocytes, endoscopy showing PMC or colitis, characteristic changes on computed tomography (CT) (thickened bowel restricted to the colon, often associated with ascites), fever, hypoalbuminemia, and leukocytosis, sometimes with a leukemoid reaction. Nearly all cases of CDI are associated with diarrhea, but occasional postoperative patients will not have this owing to ileus. The laboratory clue that best predicts this diagnosis and its severity is the white blood cell (WBC) count. The average is about 15,000 cells/mL, but it may be much higher with counts over 20,000 or even 50,000 cells/mL. This strongly supports the CDI diagnosis and predicts severe disease.8

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

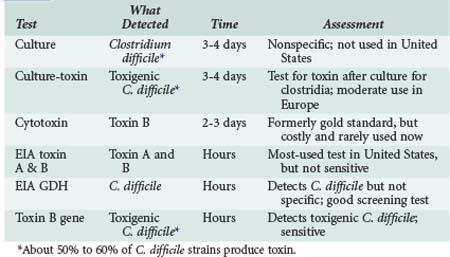

The diagnosis is based on detection of the C. difficile (culture, EIA for glutamine dehydrogenase or polymerase chain reaction [PCR] for toxigenic C. difficile) or its toxins, designated toxin A and toxin B (enzyme immunoassay [EIA] for toxins A + B, or cytotoxin assay). Relative merits are shown in Table 146-1.

Treatment

Treatment

Most important to treatment of CDI is discontinuing the implicated antibiotic. If there is a need for antibiotic treatment, select a drug that is unlikely to cause CDI (narrow-spectrum β-lactams, macrolides, aminoglycosides, antistaphylococcal drugs, tetracyclines; Table 146-2). The two favored drugs for treatment of CDI are metronidazole and vancomycin, both given by mouth.1,6,7 Metronidazole is often preferred because it is less expensive. Earlier studies showed it to work as well as vancomycin, but more recent trials show oral vancomycin is superior to metronidazole in seriously ill patients,8 defined as having a WBC over 15,000 cells/mL or elevated creatinine to 1.5 × baseline.6 Other markers of serious disease are albumin less than 2 mg/dL, admission to the ICU for CDI, pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) on endoscopy, or pancolitis on CT scan.9 Vancomycin is superior to metronidazole owing to pharmacology.8 All C. difficile are in the colon, so the challenge is getting an active drug to the colonic lumen. Vancomycin is not absorbed, so it all goes to the colon when given orally; metronidazole given orally is nearly completely absorbed, so it gets to the colon primarily through an inflamed colonic mucosa. Most patients improve with resolution of diarrhea in 3 to 5 days.1,7 Patients who are seriously ill (megacolon, septic shock, WBC >30,000/mL, lactate >5) and fail to respond to standard treatment should be considered for colectomy.9 The major indications are failure to respond to standard medical management and colonic perforation.

| Category | Characteristics | Treatment Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Mild-moderate | WBC ≤ 15,000/mL and creatinine < 1.5 × baseline | Metronidazole 500 mg PO 3×/d × 10-14 days |

| Severe | WBC > 15,000/mL or creatinine > 1.5 × baseline | Vancomycin, 125 mg 4×/d PO × 10-12 days |

| Severe and complicated | Hypotension, shock, ileus or megacolon | Vancomycin, 500 mg PO 4×/d by NG tube or by rectum, plus Metronidazole 500 mg IV q 8 h |

| First relapse Second relapse |

As above Vancomycin, standard dose, then taper and/or pulse |

PO, per os (orally); NG, nasogastric; WBC, white blood cell.

Adapted from Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010;31:431-55.

Prevention

Prevention

Prevention of C. difficile includes: (1) surveillance to detect epidemics, (2) methods to prevent transmission of C. difficile, and (3) strategies to prevent unnecessary exposure to antibiotics, especially those most likely to induce CDI. For surveillance purposes, a rate of more than 4-10/10,000 patient days or 3-8/1000 admissions is regarded as excessive.6,10 For prevention of horizontal transmission, the key preventive measures are hand hygiene (use of soap and water in epidemics), barrier precautions, use of private rooms or cohorting of case patients until diarrhea resolves, and disinfection of environmental surfaces using sporicidal agents such as chlorine-containing agents. For hand hygiene, it is noted that soap and water in place of alcohol-based hygiene is recommended only in C. difficile epidemics. Patients with CDI should have their own commode and room (or be cohorted) until diarrhea resolves. The decision to stop barrier precautions or for patient transfer should not be based on stool studies for C. difficile, since there is no test to determine response to treatment. Avoidance of unnecessary antibiotic use with antibiotic stewardship programs is an important general practice principle but is especially important in controlling this complication. With epidemics as described by surveillance rates, it is important to define the associated antimicrobials. Published reports indicate control of epidemics through restraining or eliminating use of clindamycin, cefotaxime, or fluoroquinolones when these agents were implicated.6 Identification of the serotype of the implicated strain (e.g., NAP-1) may facilitate epidemiologic investigations in outbreaks. However, this requires stool culture for C. difficile, which most hospital labs do not usually do, and referral of the strain to a reference lab for serotyping.

Complications

Complications

The major complications of C. difficile for the intensivist are toxic megacolon and sepsis.1,6,9 Toxic megacolon poses two problems: first is the severity of this complication per se, but also important is the inability to deliver vancomycin to the site of infection. Methods to deal with toxic megacolon are included in Table 146-2. For rectal instillations, the vancomycin is diluted with saline and delivered by enema, with a goal to get it to the right colon. Some patients will be severely ill with signs of sepsis, but bacteremia with enteric bacteria is rare, and C. difficile bacteremia as a complication of CDI has not been reported. C. difficile perforation has been reported as a complication of megacolon but is unusual. Most seriously ill patients respond to standard management of sepsis, with particular attention to rehydration, while attempting to control disease with oral vancomycin and IV metronidazole.

Key Points

Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:758-764.

A review of CDI including the recent developments with the NAP-1 strain.

Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:334-339.

McFarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, Stamm WE. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:204-210.

McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, Owens, RCJr, Kazakova SV, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2433-2441.

Lyras D, O’Connor JR, Howarth PM, Sambol SP, Carter GP, et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176-1179.

The role of toxin B as an essential component of the pathophysiology of CDI.

Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-455.

Lowy I, Molrine DC, Leav BA, Blair BM, Baxter R. Treatment with monoclonal antibodies against Clostridium difficile toxins. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:197-205.

Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:302-307.

Lamontagne F, Labbé AC, Haeck O, Lesur O, Lalancette M, et al. Impact of emergency colectomy on survival of patients with fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis during an epidemic caused by a hypervirulent strain. Ann Surg. 2007;133:718-720.

McDonald LC, Coignard B, Dubberke E, Song X, Horan T, et al. Recommendations for surveillance of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:140-145.

1 Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:758-764.

2 Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:334-339.

3 McFarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, Stamm WE. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:204-210.

4 McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, Owens RCJr, Kazakova SV, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2433-2441.

5 Lyras D, O’Connor JR, Howarth PM, Sambol SP, Carter GP, et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176-1179.

6 Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-455.

7 Lowy I, Molrine DC, Leav BA, Blair BM, Baxter R. Treatment with monoclonal antibodies against Clostridium difficile toxins. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:197-205.

8 Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:302-307.

9 Lamontagne F, Labbé AC, Haeck O, Lesur O, Lalancette M, et al. Impact of emergency colectomy on survival of patients with fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis during an epidemic caused by a hypervirulent strain. Ann Surg. 2007;133:718-720.

10 McDonald LC, Coignard B, Dubberke E, Song X, Horan T, et al. Recommendations for surveillance of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:140-145.