CHAPTER 50 CLINICAL SPECTRUM

The clinical spectrum of epilepsy is vast. In terms of symptomatology, the expression of epileptic seizures is very diverse and depends on the function of the part of the brain that is involved by the abnormal neuronal discharge. The age of the affected individual at disease onset and during its evolution ranges from neonates to elderly persons, leading to multiple clinical scenarios. Certain epileptic disorders that occur early in life may have severe consequences on the developing brain. Another key determinant of epileptic diseases is the etiological background, which may include genetic factors, acquired brain lesions, or progressive brain dysfunction but may also remain unknown. This diversity and sometimes complexity are well reflected by the classifications—classification of epileptic seizures on the one hand and classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes on the other. All of these parameters should be analyzed by a clinician in a syndromic approach to the patient’s condition. This type of approach facilitates development of a rational management strategy, with selection of the most appropriate drugs as a function of their spectrum of efficacy, and establishes a reasonably reliable prognosis. The severity of the different epileptic syndromes varies from very benign and transient conditions to devastating diseases.

DEFINITIONS AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

An epileptic seizure can be defined as a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal or excessive synchronous brain activity.

An epileptic seizure can be defined as a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal or excessive synchronous brain activity. Epilepsy is a family of disorders of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to epileptic seizures and by the neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition.

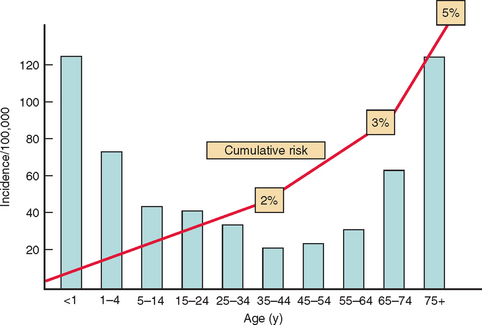

Epilepsy is a family of disorders of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to epileptic seizures and by the neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition.The overall annual incidence of epilepsy is generally believed to be around 50 per 100 000 (range, 40 to 70 per 100 000/year) in industrialized countries, but socioeconomically deprived people are at greater risk. First seizures are estimated to be around 70 per 100 000 annually. There is a mild predominance in males. The specific incidence as a function of age shows a bimodal curve, with two peaks, one in childhood, with figures of more than 100 per 100,000 during the first year of life, although there is evidence of a decrease in childhood incidence in recent decades. A second peak is observed in elderly people with an estimate of 150 per 100,000 over the age of 80 years, which is attributed to the many prevalent causes of brain damage at that age, with cardiovascular diseases being the most frequent (Fig. 50-1).

In terms of prevalence, several studies conducted in different regions of the world have suggested that epilepsy affects 5 to 8 per 1000 population. These estimates are based on individuals with active epilepsy, defined as patients with a seizure in the previous 5 years or still receiving antiepileptic drug treatment.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO EPILEPTIC DISORDERS

The next step is to characterize the epileptic seizure type relative to the list of different types defined by the International Classification of Seizures (Table 50-1). It is essential to identify or rule out seizure types by detailed questioning of patients and relatives. Localization within the brain should be specified when this is appropriate; in the case of reflex or provoked seizures, the specific stimulus should also be specified. Electroencephalographic data are often incorporated at this stage of the diagnostic process, as many seizures are also associated with specific electroclinical characteristics. Age at onset is also a critical piece of information. Certain specific seizure types may by themselves be more or less indicative of diagnostic entities with etiological, therapeutic, and/or prognostic implications.

A syndromic diagnosis should then be made whenever possible, again using the common terms proscribed by the International Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes. This syndromic diagnosis relies on the grouping of information: on seizure type or types, pattern of recurrence or frequency, age at onset, personal and familial antecedents, natural history, and other neurological and extraneurological manifestations. The electroencephalographic data, both interictal and sometimes ictal, are essential, as is a brain imaging examination. Magnetic resonance imaging is indicated in the majority of situations but can be omitted when certitude is reached about the diagnosis of an idiopathic generalized syndrome.

EPILEPTIC SEIZURES

Generalized Seizures

Atonic Seizures

They correspond to a loss of postural tone, leading to a fall or limited to a head drop. Their duration varies from seconds to minutes. The electroencephalogram usually consists of a slow and irregular discharge of spike-waves, which are usually seen in the context of childhood epileptic encephalopathies.

Partial Seizures

Simple Partial Seizures

Complex Partial Seizures

These are defined by a disturbance of consciousness, either at onset or after an initial phase of simple partial manifestations (aura). They are often accompanied by automatisms, gestural, oroalimentary (masticatory, swallowing), verbal, or more or less elaborated or adapted behavioral sequences. All of these automatisms, taken separately, have very little localizing value. Their sequence or combination of such diverse automatisms with other manifestations, however, may have some localizing value. A masticatory automatism is a good indicator of involvement of the amygdala in the context of temporal lobe seizures. The mesial temporal lobe is frequently at the origin of complex partial seizures that include an aura, often an ascending epigastric sensation with autonomic or psychic symptoms, with fear being frequent. Alteration of consciousness begins with an arrest or staring reaction, followed by oroalimentary automatisms, gestual automatisms, and limb dystonia (most often contralateral to the focus). A postictal dysphasia may be present if the dominant hemisphere is implicated. However, complex partial seizures may take their origin in other regions of the brain. The frontal lobes can generate either absence-like seizures or prominent motor automatisms.

EPILEPSIES AND EPILEPTIC SYNDROMES

The international classification (Table 50-2) may give the impression that it is simply a very long list of diseases, without providing the reader with some essential organizing notions like frequency or severity. Some syndromes are very frequent, whereas others correspond to orphan diseases, emphasizing an extraordinarily vast and diversified spectrum.

TABLE 50-2 International Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes

|

1. Focal syndromes (also partial or localization-related)

|

* Many metabolic or degenerative etiologies are possible. The progressive myoclonic epilepsies like Lafora and Unverricht-Lundborg diseases are classified here.

The current international classification is based on two main axes, or dichotomies. The first axis refers to the notion of partial versus generalized syndromes. In generalized epilepsies, all of the seizures are generalized seizures; the electroencephalographic characteristics are bilaterality, diffuseness, and symmetry. In partial or focal epilepsies, seizures take their origin in a focal or an epileptic zone, regardless of the fact that some seizures may become secondarily generalized. However, the term focal does not mean the epileptogenic region is a small, well-delineated focus of neuronal pathology. Focal seizures and syndromes are often due to diffuse and at times widespread areas of cerebral dysfunction. Furthermore, for several syndromes, it is unclear whether they are focal or generalized. In fact, there is a variety of conditions giving rise to a range of focal through generalized epilepsies that include diffuse hemispheric abnormalities, multifocal abnormalities, and bilaterally symmetrical localized abnormalities. Although concepts of partial and generalized epileptogenicity have value, perhaps more with respect to ictal events than to syndromes, it may not be appropriate or even useful to attempt to classify all seizures and syndromes within one or the other of these categories.

PROGNOSIS: FROM BENIGN CONDITIONS TO DEVASTATING DISEASES

Fish DE, et al, editors. The Treatment of Epilepsy. London: Blackwell Science (UK), 2004.

Kotagal P, Luders H. The Epilepsies: Etiologies and Prevention. New York: Academic Press, 2001.

Shorvon S. Handbook of Epilepsy Treatment. Boston: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

Schmidt D, Schachter SC. Epilepsy: Problem Solving in Clinical Practice. New York: Taylor & Francis, 1999.