CHAPTER 11 Clinical Presentation of Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas are tumors that are derived from the meningothelial cells that invest the arachnoid membrane. Therefore, meningiomas that occur outside the brain parenchyma are extra-axial tumors.1 They are more common in women than in men, with 65% of all diagnosed meningiomas occurring in women in the fifth and sixth decades of life. They are rare in children; only 1.5% of all meningiomas occur in childhood and adolescence, with boys predominantly affected.2 The localizations and clinical manifestations of pediatric meningiomas show differences from those in adults.3 That malignant meningiomas are very destructive and grow more rapidly than benign meningiomas makes a difference in their clinical behavior, and this separates the evaluation of malignant meningiomas. Limb paresis and headache are the most common clinical signs.4 Meningiomas may arise from any part of the lining in both the cranial vault and spinal cord. They often occur along the intracranial venous sinuses, which they may invade. Meningiomas produce numerous neurologic symptoms by several mechanisms, depending on their localization, size, and the function of the particular area.5 Their symptoms and signs include headache, seizure, personality changes, parkinsonism, and focal neurologic deficits such as hemiparesis, visual field defect, and cranial nerve disturbance. Because meningiomas are very slow-growing tumors, patients may have subtle symptoms for a long time before the diagnosis is made.6 Because of slow growth, the brain adapts to changes. Compensatory mechanisms fail in the advanced stages of meningioma growth.7 Meningiomas smaller than 2.0 cm in diameter are generally discovered in a postmortem study in middle-aged and elderly persons without having caused manifestations. As many as one third of all meningiomas are asymptomatic at the time of their diagnosis and are discovered when radiologic imaging is performed for unrelated symptoms.

FOCAL NEUROLOGIC DEFICITS

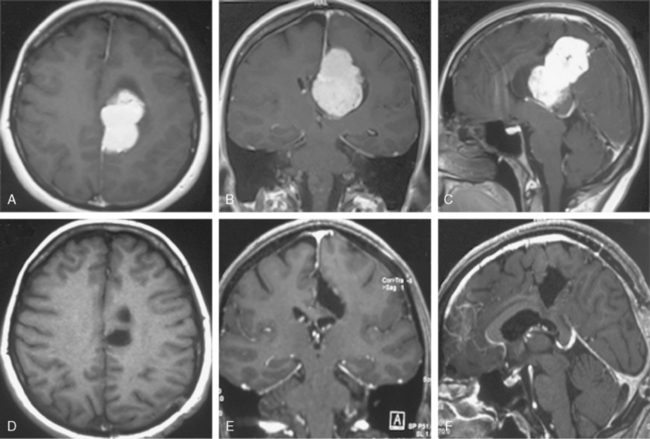

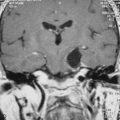

Parasagittal and falcian meningiomas are the most common localization of meningiomas (30%–50%).8 In considering the symptoms of both of these tumors, it is useful to divide them according to the area from which they arise: anterior, middle, and posterior thirds of the sagittal sinus and falx.9 Meningiomas arising from the middle third of the sagittal sinus and falx are the most common and present with focal seizures or gradual loss of motor and sensory function usually beginning in the lower extremity. Meningiomas arising from the anterior third tend to have a more insidious onset and often become large before a diagnosis is made. There may be a gradual change in personality and mental functions. Headache is common (Fig. 11-1).

Olfactory groove meningiomas can arise from arachnoidal cells along the cribriform plate and frontosphenoid suture and account for 10% of intracranial meningiomas.10 These meningiomas may slowly expand bilaterally and push on frontal lobes. The diagnosis depends on the findings of ipsilateral or bilateral anosmia or ipsilateral or bilateral blindness often with optic atrophy, headache, and mental changes.11 Inferior visual field defect is the most common sign. Olfactory groove meningiomas cause Foster Kennedy syndrome of unilateral optic atrophy and contralateral papilledema. The syndrome is originally described in these meningiomas but occurs in only a small number of patients. Other common symptoms are personality changes, cognitive decline and psychiatric disturbances.12 Mental changes such as apathy, abulia, akinesia, confusion, forgetfulness, and so forth are noticed particularly by family members over several years, so these symptoms may be the initial presentation.

Suprasellar meningiomas originating from the tuberculum sellae,13 diaphragma sellae and planum sphenoidale are uncommon. They represent about 3% to 10% of all intracranial meningiomas.1 The symptoms of suprasellar meningiomas include visual loss, loss of smell, mental disorders, epilepsy, and headache.14 Asymmetric visual loss, either monocular or binocular, is the most common symptom leading to diagnosis. Other symptoms such as dizziness, incontinence, tinnitus, fainting spells, motor deficits, somnolence, and endocrinologic disturbances are noted. Among suprasellar meningiomas, tuberculum sellae meningiomas are the most common. They cause bitemporal hemianopia, in contrast to other suprasellar meningiomas, and usually no endocrinologic disturbances are present. Cushing was the first to describe the syndrome caused by tuberculum sellae meningiomas.15,16

Sphenoid wing meningiomas are located over the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone. The sphenoid wing is the third most common site for intracranial meningiomas.17 As meningiomas that are situated in sphenoid wing grow, they may expand medially into the wall of the cavernous sinus, anteriorly into the orbit, and laterally into the temporal bone. Growth of tumors in the inner wing and orbit most often causes direct damage to the optic nerve, leading mainly to progressive decrease in visual acuity; loss of color vision, especially central defects in the visual fields; and afferent pupillary defects. If meningiomas continue to grow and compress the optic nerve totally, first optic atrophy in one eye occurs, then blindness develops. Tumors growing into cavernous sinus cause damage to cranial nerves (occulomotor, trochlear, abducens, ophthalmic, and maxillary division of trigeminal nerve), sympathetic fibers, and the venous circulation. Thus damage to these structures leads to diplopia, Horner’s syndrome, palpebral swelling, and exophthalmos. Most prominent among these symptoms is a slowly developing unilateral exophthalmos. The abducens nerve is often the first affected cranial nerve, leading to diplopia with lateral gaze. Globoid type meningiomas may extend intracranially, so they may lead to seizure disorders or impairment of neurologic functions such as motor weakness. This type of meningioma causes different clinical syndromes. Variants of this clinical syndrome include anosmia, oculomotor palsies, Tolosa–Hunt syndromes (painful ophthalmoplegia), sometimes Foster Kennedy syndrome (papilledema of the other eye), and mental changes.

Clinoidal meningiomas are also termed medial or inner wing sphenoidal meningiomas. They arise from the meningeal covering of the anterior clinoid process.18 Symptoms and signs include visual disturbances, involvement of cranial nerves (III, IV, V, VI, and VII), headache, and seizure (Fig. 11-2).

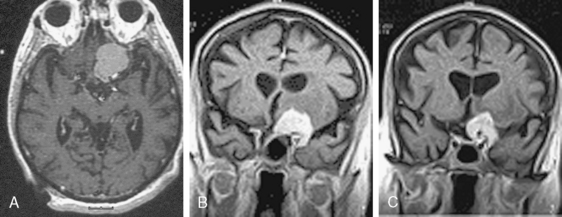

Optic nerve sheath meningiomas are responsible for 1% to 2% of all meningiomas. The symptoms of optic nerve sheath meningiomas depend on localization in the orbit, the optic canal, or intracranially.19 They are usually unilateral. Although patients typically present with initially decreased or blurred vision in the affected eye, at examination the vision acuity may be normal. In large tumors, blindness develops and swollen optic disc or optic atrophy and optociliary shunt vessels are seen on funduscopic examination.20,21 The predominant feature of these tumors is early visual loss (Fig. 11-3). Neurofibromatosis type II is associated with meningiomas, especially optic nerve sheath meningiomas.22 In these patients, family history is important.

Cavernous sinus meningiomas involving the cavernous sinus may start in the sinus or grow into it as part of a larger tumor involving the medial sphenoid wing, orbit, other areas of the middle fossa, or clivus or petrous bone. Their symptoms are similar to those discussed previously in sphenoid wing meningiomas, but they may be more mild or nonprogressive.23 Patients with these tumors are usually admitted to clinics with complaints of visual loss.

Intraventricular meningiomas are usually located in the trigone of the lateral ventricle.24 Lateral ventricular meningiomas are often silent tumors with papilledema, headache, weakness, mental changes, and visual field defects as the most common problems.

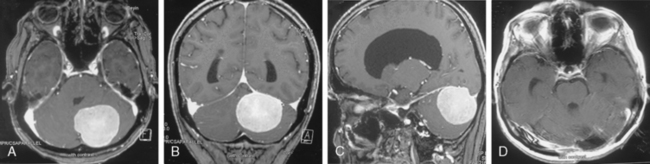

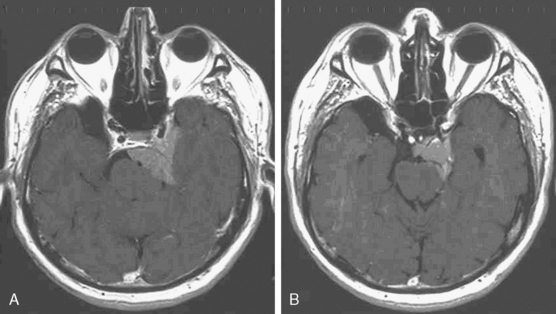

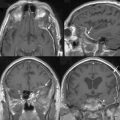

Infratentorial (posterior fossa) meningiomas are responsible for 10% of all meningiomas.25 Meningiomas are classified as petroclival, posterior surface of the petrous bone (cerebellopontine angle), cerebellar convexity, foramen magnum, and jugular foramen. Symptoms and signs include headache, cerebellar dysfunction, and tinnitus (Fig. 11-4).

Cerebellopontine angle meningiomas are the second most common tumor to arise in the cerebellopontine angle (CPA) after acoustic neuromas. CPA meningiomas arise lateral to the trigeminal nerve. Symptoms and signs of meningiomas localized to the CPA include loss of hearing, headache, cerebellar dysfunction, facial pain, or numbness secondary to involvement of the trigeminal nerve, long tract signs arising from involvement of the corticospinal tract, and vestibular dysfunction secondary to involvement of the vestibulocochlear nevre. Meningiomas also may involve the lower cranial nerves.26

Cerebellar convexity meningiomas constitute 1% to 2% of all meningiomas and 10% to 20% of posterior fossa meningiomas.25 They are frequently adjacent to the transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus, and torcular Herophili. They may attach to the cerebellar dura, the petrous dura, or the tentorium. Some of these tumors may become large before they produce symptoms. Patients may present with symptoms and signs characteristic of posterior fossa lesions: headache and cerebellar dysfunction.

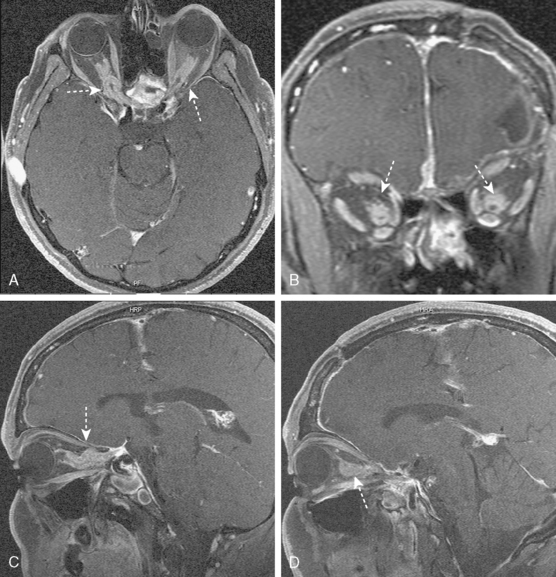

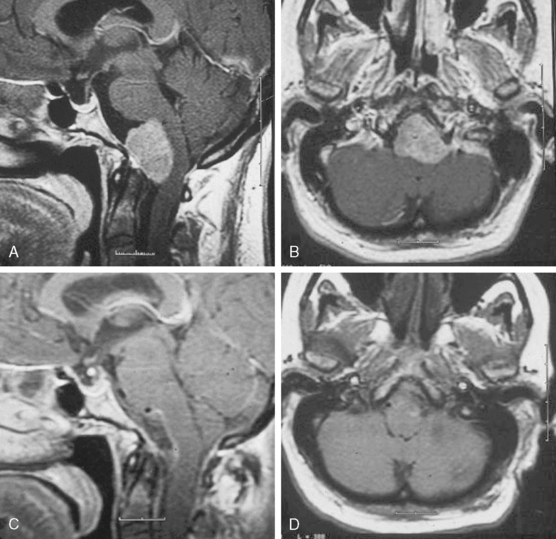

Petroclival meningiomas arise from the clivus and the petrous bone medial to the fifth cranial nerve. They may grow out along the petrous pyramid or into the cavernous sinus and middle fossa. Symptoms are secondary to several factors, the first being involvement of cranial nerves, especially the first trigeminal, vestibulocochlear, facial, abducens, and oculomotor nerves (Fig. 11-5). Deficits of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI are uncommon. Other symptoms include cerebellar or brain stem compression with involvement of the corticospinal tract. Rarely, petroclival meningiomas may invade the basilar artery and its branches and thus cause basilar arterial insufficiency.

Foramen magnum meningiomas symptoms and signs include unilateral neck pain; Lhermitte’s sign; involvement of the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory cranial nerves; cold dysesthesias; progression of motor and sensory deficits starting in one arm and spreading to the other limbs; and atrophy of the hand muscles (Fig. 11-6). Patients may also demonstrate slow athetosis-like movements of their arms, hands, and particularly fingers due to disturbance in position sense.

Jugular foramen meningiomas are an unusual location for meningiomas, accounting for 4% of posterior fossa meningiomas. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa involve the jugular foramen more often by extension from another site of origin. The clinical presentation of jugular foramen meningiomas is a combination of lower cranial nerve involvement (IX, X, XI, and XII). Patients with these tumors may also complain of hearing loss, pulsatile tinnitus, and middle ear mass.27,28

Spinal meningiomas are usually located in the thoracic region.29 In one study, a comprehensive series of 174 spinal meningiomas, 70% of the patients had little or no neurologic impairment and 30% had a significant or severe impairment preoperatively.30 The predominant symptom is pain in patients with these meningiomas.29 Spinal meningiomas may give rise to a Brown–Sequard syndrome (contralateral decreased pain sensation, ipsilateral weakness, decrease in position sense), sphincteric weakness, and eventually complete quadriparesis or paraparesis.

INCREASED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

Some tumor locations are more associated with the symptoms and signs of increased ICP than others. Intraventricular meningiomas are commonly seen in the lateral ventricles and occur in the third and fourth ventricles as well.31 Presentation is in the form of increased ICP with no localizing features. Hydrocephalus occurs due to obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways.24 A meningioma arising from the posterior third part of parasagittal and falcian meningiomas often presents with headache or other symptoms and signs of increased ICP. There may be visual symptoms, often with visual field defects. Patients with sphenoid wing, cerebellopontine angle, cerebellar convexity, and petroclival meningiomas often present only with signs of increased ICP including headache and swollen optic disc.32 Obstructive hydrocephalus can be seen during meningiomas growth, especially posterior fossa meningioma, due to obstruction of CSF pathways.33

PARKINSONISM

Although parkinsonism can develop in association with any type of brain tumor, it develops most frequently in association with meningiomas located at the sphenoid ridge, parasagittal, and frontal sites. Functional abnormality in the nigrostriatal system due to chronic mechanical compression of the system by a sizable brain tumor seems to contribute to the pathogenesis of the parkinsonism.34 The extension of the meningioma and of the peritumoral edema may play an important role in compressing and consequently impairing perfusion of the basal ganglia region. The complete surgical removal of the meningiomas mostly remedies the parkinsonism.35

SEIZURES

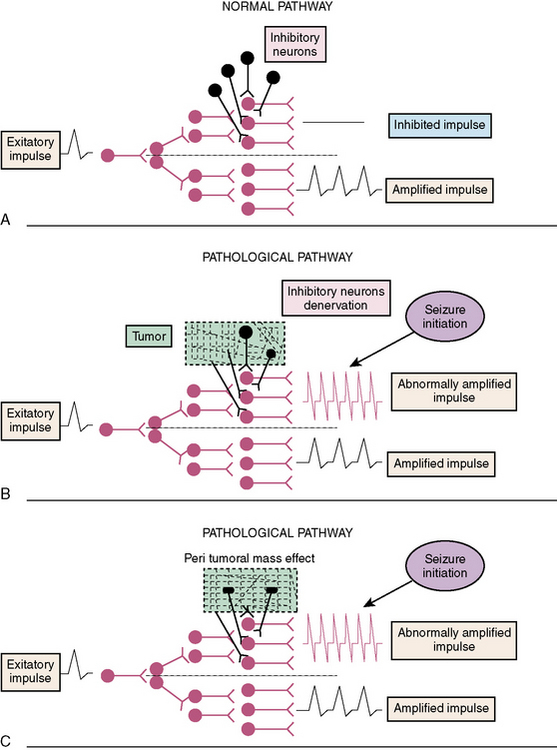

Approximately 3% to 12% of adult-onset and 0.2% to 6% of childhood-onset cases of epilepsy are caused by central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms.36–38 Seizure, which is significantly more common in patients with primary CNS neoplasms than metastases, is often the first initial symptom.39 Supratentorial meningiomas seizures frequencies were 29% to 67%.40,41 The type of seizure frequently relates to the part of the brain involved by the tumor.42,43 Lesions in the temporal lobe frequently cause complex partial seizures, absence, and gustatory and olfactory auras. Partial motor or sensory seizures are common with perirolandic lesions. Partial seizures are also frequent with tumors in the supplementary motor cortical area and the second somatic sensory area. Generalized tonic–clonic type seizures may occur as a secondary generalization after a partial seizure.44 Brain tumors are responsible for 3.5% to 6.3% of all status epilepticus cases.45,46 Nonconvulsive status epilepticus should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute mental status change in patients with brain tumor. Among primary CNS neoplasms, tumor location was associated with a trend in seizure risk: parietal (80%), temporal (74%), and frontal (62%).47 Most patients with meningiomas (86%), astrocytomas (80%), and tumor-associated epilepsy have a focal component to their seizures.48,49 However, in almost one third of patients with brain tumors and epilepsy, the epileptogenic focus does not correspond to tumor location. This phenomenon is called secondary epileptogenesis,50 implying that an actively discharging epileptogenic region induces similar paroxysmal activity in regions distant from the original site. Seizures are probably multifactorial, and incidence depends on tumor type and location.51–53 The pathophysiologic changes related to epileptic activity in peri- and intratumoral tissue are complex and have been only partly understood until now. There is also evidence, however, that seizures in the setting of a brain tumor may be due to alterations in the brain tissue surrounding the tumor, rather than within the tumor. Possible mechanisms involve different structural, biochemical, and histologic tumor-related alteration. Several mechanisms may be responsible for tumor-related epilepsy (Fig. 11-7). These include metabolic imbalance, pH abnormalities, amino acid and neuroreceptor disturbances, enzymatic changes, and immunologic activity.54–56 Cortical inhibitory (γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA], taurine) and excitatory (glutamate, aspartate) amino acids, and ions (magnesium, iron) are known to be affected by perilesional structural changes. Extracellular pH modulates neuronal excitability. The pH in the peritumoral cortex is significantly more alkaline than normal cortex.57 Changes of pH in peri- and intratumoral tissue could cause an imbalance in the excitatory and inhibitory stimuli.

Involvement of glutamate signaling in the brain tumor has been under investigation for many years.58 Glutamate signaling involves a large group of proteins and glutamate transporters with their effectors. Glutamate is one of the major excitatory neurotransmitters. Even levels as low as 2 to 5 μmol/L of extracellular glutamate are sufficient to cause excitotoxicity in the CNS.57,59 Perilesional immunoreactivity of glutamate decarboxylase and abnormal glutamatergic transmission are associated with increased glutamate concentration and increased excitability.60,61 Glutamate levels in the peritumoral edema of nonglial tumors were significantly elevated compared with edema associated with glial tumors or normal white matter.62 The pathogenesis of tumor-related seizures may involve a deficiency of GABA-mediated inhibition.63 Gangliogliomas constitute the most frequent tumor entity in young patients undergoing surgery for intractable epilepsy. In gangliomas, synaptic transmission, including GABA receptor signaling, was an underexpressed process compared with control tissue.64 In addition, benzodiazepine-GABA(A) receptor binding is very low in dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor.65 Brown and colleagues examined the localization and function of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor in tumors.66 In glioblastoma biopsies, the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor is expressed in the nuclei of cells, while it is found in the cytosol of astrocytomas, and is absent from meningioma and medulloblastoma tumor biopsies.

Relatively slow-growing tumors are more epileptogenic, whereas the incidence of seizures is lower with more rapidly growing tumors (Table 11-1). The mechanisms of epileptogenesis vary with different tumors, for example, gliomas (intracerebral) infiltrate the surrounding brain tissue while meningiomas (extracerebral) do not infiltrate but simply compress or distort it. In meningiomas, seizures may be the result of a number of potential pathophysiologic mechanisms as follows:47,67,68 (1) morphologic changes in peritumoral brain tissue (aberrant neuronal migration), (2) compression of the underlying cortex, (3) local edema, (4) microscopic tumor invasion, (5) local cortical irritability, and (6) imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory mechanisms.

| Tumor type | Seizure incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Oligodendroglioma | 70–92 |

| Astrocytoma | 46–83 |

| Meningioma | 29–70 |

| Glioblastoma | 27–40 |

| Metastase | 25–35 |

Data from Salmaggi et al.,39 Penfield et al.,40 Chan et al.,41 Kurland et al.,43 Lynam et al.,47 Sutherland et al.,51 Whittle et al.,52 Beaumont et al.,56 Villemur et al.,67 Moots et al.,74 Sirven et al.,82 Vecht et al.83

Between 40% and 50% patients with either partial or generalised preoperative epilepsy caused by meningiomas continue to suffer seizures even after grade I or II resection.41,48 Few studies focus on seizure outcomes after resections of meningiomas. Flyger and colleagues studied the neogenesis of seizure disorders in the postoperative period.69 They observed that 41.1% of patients with no preoperative seizure disorder developed epilepsy postoperatively. Similarly, Foy and colleagues reported a 22% risk of postoperative seizures after meningioma resection.70 Chozick and colleagues assessed the incidence of postoperative seizures in 158 patients with meningiomas. They identified six clinical variables predictive of the occurence of postoperative seizures:71 (1) preoperative seizure history, (2) preoperative language disturbance, (3) parietal location of the tumor, (4) extent of tumor removal, (5) postoperative medication status, and (6) postoperative hydrocephalus. In contrast, it has been shown that there was no statistically significant association between extent of surgical resection and the development of delayed seizures.72 Preoperative and early postoperative EEG after meningioma surgery is not helpful in determining the risk of postoperative seizures.73 Early-onset postoperative seizure appeared in 66.7% within the first 48 hours after surgery.74 Of the patients with postoperative seizure, 71.2% were seizure-free after 1 year of anticonvulsant therapy. Between 15% and 40% of previously seizure-free patients with meningiomas will experience postoperative seizures.41,48,69,70 These results suggest that some tumors alter local brain tissue homeostasis and neuronal discharges.

SEIZURE MANAGEMENT

Overall, 60% of patients with primary brain tumors present with epilepsy and another 10% to 20% of patients develop epilepsy later in the course of their disease.49,73 Tumor-related seizures are often refractory to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).73,75,76 Optimal management of seizures with AEDs is unclear in brain tumor patients. No AED has been proven clearly superior for tumor-related epilepsy.77 Several factors contribute to difficulties in treatment of tumor-related seizures, such as tumor growth and drug interactions. One of the main reasons for poor seizure control may result from the insufficient or even absent influence of the currently available AEDs. Schaller and Ruegg suggested three reasons for the failure of AEDs to prevent seizures in patients with brain tumors78: (1) Most AEDs act on excitatory mechanisms by blocking ions channels or augmenting GABA. But seizures due to tumors may result from other mechanisms including altered peritumoral changes in regional metabolism. (2) Seizures may occur because of tumor progression, which is not affected by AED. (3) There is an insufficient serum concentration of AEDs due to drug interactions or reduced plasma protein levels.

Several serious adverse effects can occur with AED use.79 Serious rash, including Stevens Johnson syndrome, can occur with agents such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. Carbamazepine, valproic acid, phenytoin, and phenobarbital have potential hematologic effects when used alone. Levetiracetam, which has less allergenicity and fewer medical interactions, seems an attractive alternative that is more frequently recommended.76,77,80,81 Lynam and colleagues analyzed the management of seizures in 147 patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors.47 Phenytoin was the most common agent to treat patients who presented with seizures, it was also the most common medication to be discontinued in favor of levatiracetam. The most common side effects necessitating switching from phenytoin to levetiracetam were rash and elevated liver enzymes. Among their patients with primary CNS tumors and seizures, 75% required monotherapy and 23% required polytherapy for seizure management. In the metastatic group, 83% were managed with monotherapy.

Phenytoin, phenobarbital, and valproate are the only AEDs subjected to prospective, randomized, controlled trials of seizure prophylaxis in patients with cerebral tumors. A meta- analysis in five randomized controlled trials showed that prophylaxis with AEDs (phenytoin, phenobarbital, or valproic acid) were not effective in primary brain tumors, meningiomas, and brain metastases.82 Further, neither the tumor type nor the type of surgery received by patients influenced seizure activity. AEDs not only are ineffective seizure prophylaxis in patients with cerebral tumors, but also may cause serious side effects.83 It is known that AED side effects are seen more frequently in patients with brain tumors (20%–40%) than in the general population of patients with epilepsy.75,84

Based on randomized studies, the Guidelines of the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend prophylactic use of AEDs in brain tumors.75 After brain surgery, AEDs can be discontinued after 1 week in patients without a history of previous seizures. In patients with brain tumors and refractory epilepsy despite careful medical treatment, neurosurgical treatment must be considered. Stereotactic radiosurgery is also used to treat meningiomas that are nonoperable, small, recurrent, or a result of a subtotal resection.85,86 The goal is to prevent further tumor growth and preserve normal neurologic function. This is a safe and effective option for primary or adjuvant therapeutic strategy.87,88

[1] Black P.M. Meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:643.

[2] Rushing E.J., Olsen C., Mena H., et al. Central nervous system meningiomas in the first two decades of life: a clinicopathological analysis of 87 patients. Neurosurgery. 2005;103(Suppl. 6):489.

[3] Ferrante L., Acqui M., Artico M., Mastronardi L., Fortuna A. Pediatric intracranial meningiomas. Br J Neurosurg. 1989;3:189.

[4] Jaaskelainen J., Haltia M., Servo A. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: radiology, surgery, radiotherapy and outcome. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:233.

[5] Fisher J.L., Schwartzbaum J.A., Wrensch M., Berger M.S. Evaluation of epidemiologic evidence for primary adult brain tumor risk factors using evidence-based medicine. Prog Neurol Surg. 2006;19:54.

[6] Kalamarides M., Goutagny S. Meningiomas. Rev Prat. 2006;56(16):1792.

[7] Sırven J.I., Malamut B.L. Clinical Neurology of the Older Adult. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2002.

[8] Tuna M., Göçer A.I., Gezercan Y., Vural A., Ildan F., Haciyakupoglu S., et al. Huge meningiomas: a review of 93 cases. Skull Base Surg. 1999;9(3):227.

[9] Maxwell R.E., Chou S.N. Parasagittal and Falx Meningiomas. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company, 1991.

[10] Hentschel S.J., DeMonte F. Olfactory groove meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14:e4.

[11] Medrano V., Mallada Frechin J., López Hernández N., Fernández Izquierdo S., Piqueras Rodríguez L. Olfactory seizures and parasellar meningioma. Rev Neurol. 2004;38(5):435.

[12] Vieregge P., Reinhardt V., Kretschmar C. Meningioma in psychiatry. Clinico-pathologic contribution to differential cerebral organic psychosyndrome diagnosis in middle and advanced age. Schweiz Arch Neurol Psychiatr. 1990;141:269.

[13] Pamir M.N., Ozduman K., Belirgen M., Kilic T., Ozek M.M. Outcome determinants of pterional surgery for tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147(11):1121.

[14] Brihaye J., Brihaye-van Geertruyden M. Management and surgical outcome of suprasellar meningiomas. Acta Neurochir [Suppl] (Wien). 1988;42:124.

[15] Maurice V., Ropper A.H. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001.

[16] Al Mefty O., Smith R.R. Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press, 1999.

[17] Patankar T., Prasad S., Goel A. Sphenoid wing meningioma—an unusual cause of duro-optic calcification. J Postgrad Med. 1997;43(2):48.

[18] Pamir M.N., Belirgen M., Ozduman K., Kılıç T., Ozek M. Anterior clinoidal meningiomas: analysis of 43 consecutive surgically treated cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008. May 29. [Epub ahead of print]

[19] Miller N.R. Primary tumours of the optic nerve and its sheath. Eye. 2004;18:1026.

[20] Dutton J.J. Optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Surv Ophthalmol. 1992;37(3):167.

[21] Saeed P., Rootman J., Nugent R.A., White V.A., Mackenzie I.R., Koornneef L. Optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(10):2019.

[22] Bosch M.M., Wichmann W.W., Boltshauser E., Landau K. Optic nerve sheath meningiomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(3):379.

[23] Jacob M., Wydh E., Vighetto A., Sindou M. Visual outcome after surgery for cavernous sinus meningioma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150(5):421.

[24] Bhatoe H.S., Singh P., Dutta V. Intraventricular meningiomas: a clinicopathological study and review. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20(3):E9. 15

[25] Roberti F., Sekhar L.N., Kalavakonda C., Wright D.C. Posterior fossa meningiomas: surgical experience in 161 cases. Surg Neurol. 2001;56:8.

[26] Voss N.F., Vrionis F.D., Heilman C.B., Robertson J.H. Meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle. Surg Neurol. 2000;53:439.

[27] Gilbert M.E., Shelton C., McDonald A., et al. Meningioma of the jugular foramen: glomus jugulare mimic and surgical challenge. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:25.

[28] Mcdonald A., Salzman K.L., Harnsberger H.R., et al. Primary jugular foramen meningioma: imaging appearance and differentiating features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:373.

[29] Peker S., Çerçi A., Özgen S., et al. Spinal meningiomas: evaluation of 41 patients. J Neurosurg Sci. 2005;49:7.

[30] Solero C.L., Fornari M., Giombini S., et al. Spinal meningiomas: review of 174 operated cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:153.

[31] McDermott M.W. Intraventricular meningiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14(4):559.

[32] Lyngdoh B.T., Giri P.J., Behari S., Banerji D., Chhabra D.K., Jain V.K. Intraventricular meningiomas: a surgical challenge. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(5):442.

[33] Voss N.F., Vrionis F.D., Heilman C.B., Robertson J.H. Meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle. Surg Neurol. 2000;53:439.

[34] Kondo T. Brain tumor and parkinsonism. Nippon Rinsho. 1997;55(1):118.

[35] Salvati M., Frati A., Ferrari P., Verrelli C., Artizzu S., Letizia C. Parkinsonian syndrome in a patient with a pterional meningioma: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2000;102(4):243.

[36] Bromfield E.B. Epilepsy in patients with brain tumors and other cancers. Rev Neurol Dis. 2004;1(Suppl. 1):S27.

[37] Ibrahim K., Appleton R. Seizures as the presenting symptom of brain tumours in children. Seizure. 2004;13:108.

[38] Wyllie E. The Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

[39] Salmaggi A., Riva M., Silvani A., Merli R., Tomei G., Lorusso L., et al. Lombardia Neuro-oncology Group. A multicentre prospective collection of newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients in Lombardia, Italy. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(4):227.

[40] Penfield W., Erickson T.C., Tarlov I. Relation of intracranial tumours and symptomatic epilepsy. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1940;44:300.

[41] Chan R.C., Thompson G.B. Morbidity, mortality, and quality of life following surgery for intracranial meningiomas. A retrospective study in 257 cases. J Neurosurg. 1984;60(1):52.

[42] Chang J.H., Kim J.A., Chang J.W., Park Y.G., Kim T.S. Sylvian meningioma without dural attachment in an adult. J Neurooncol. 2005;74(1):43.

[43] Kurland L.T., Schoenberg B.S., Annegers J.F., Okazaki H., Molgaard C.A. The incidence of primary intracranial neoplasms in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935–1977. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1982;381:6.

[44] Regis J., Sanson M., Kalamarides M. Recurrent multiple meningioma and generalized seizure. Neurochirurgie. 2005;51(2):129.

[45] Scholtes F.B., Renier W.O., Meinardi H. Generalized convulsive status epilepticus: causes, therapy, and outcome in 346 patients. Epilepsia. 1994;35(5):1104.

[46] Hui A.C., Lam A.K., Wong A., Chow K.M., Chan E.L., Choi S.L., et al. Generalized tonic-clonic status epilepticus in the elderly in China. Epileptic Disord. 2005;7(1):27.

[47] Lynam L.M., Lyons M.K., Drazkowski J.F., Sirven J.I., Noe K.H., Zimmerman R.S., et al. Frequency of seizures in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors: a retrospective review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109(7):634.

[48] Ramamurthi B., Ravi B., Ramachandran V. Convulsions with meningiomas: incidence and significance. Surg Neurol. 1980;14(6):415.

[49] Hildebrand J., Lecaille C., Perennes J., Delattre J.Y. Epileptic seizures during follow-up of patients treated for primary brain tumors. Neurology. 2005;65:212.

[50] Morrell F. Varieties of human secondary epileptogenesis. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1989;6(3):227.

[51] Sutherland G.R., Florell R., Louw D., Choi N.W., Sima A.A. Epidemiology of primary intracranial neoplasms in Manitoba. Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14(4):586.

[52] Whittle I.R., Beaumont A. Seizures in patients with supratentorial oligodendroglial tumours. Clinicopathological features and management considerations. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;135(1–2):19.

[53] Bianchi L., De Micheli E., Bricolo A., Ballini C., Fattori M., Venturi C., et al. Della Corte LExtracellular levels of amino acids and choline in human high grade gliomas: an intraoperative microdialysis study. Neurochem Res. 2004;29(1):325.

[54] Bateman D.E., Hardy J.A., McDermott J.R., Parker D.S., Edwardson J.A. Amino acid transmitter levels in gliomas and their relationship to the incidence of epilepsy. Neurol Res. 1988;10:112.

[55] Tada M., deTribolet N. Recent advances in immunobiology of brain tumours. J Neurooncol. 1993;17:261.

[56] Beaumont A., Whittle I.R. The pathogenesis of tumour associated epilepsy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142:1.

[57] Gerweck L.E., Seetharman K. Cellular pH gradient in tumour versus normal tissue-potential exploitation for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1194.

[58] Takano T., Lin J.H., Arcuino G., Gao Q., Yang J., Nedergaard M. Glutamate release promotes growth of malignant gliomas. Nat Med. 2001;7:1011.

[59] Van Den Bosch L., Van Damme P., Bogaert E., Robberecht W. The role of excitotoxicity in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:1068.

[60] Lyons S.A., Chung W.J., Weaver A.K., Ogunrinu T., Sontheimer H. Autocrine glutamate signaling promotes glioma cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67(19):9463.

[61] Ishiuchi S., Yoshida Y., Sugawara K., Aihara M., Ohtani T., Watanabe T., et al. Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors regulate growth of human glioblastoma via Akt activation. J Neurosci. 2007;27(30):7987.

[62] Kimura T., Ohkubo M., Igarashi H., Kwee I.L., Nakada T. Increase in glutamate as a sensitive indicator of extracellular matrix integrity in peritumoral edema: a 3.0-tesla proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(4):609.

[63] Irlbacher K., Brandt S.A., Meyer B.U. In vivo study indicating loss of intracortical inhibition in tumor-associated epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(1):119.

[64] Aronica E., Boer K., Becker A., Redeker S., Spliet W.G., van Rijen P.C., et al. Gene expression profile analysis of epilepsy-associated gangliogliomas. Neuroscience. 2008;151(1):272.

[65] Richardson M.P., Hammers A., Brooks D.J., Duncan J.S. Benzodiazepine-GABA(A) receptor binding is very low in dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor: a PET study. Epilepsia. 2001;42(10):1327.

[66] Brown R.C., Degenhardt B., Kotoula M., Papadopoulous V. Location-dependent role of the human glioma cell peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor in proliferation and steroid biosynthesis. Cancer Lett. 2000;156(2):125.

[67] Villemure J.G., de Tribolet N. Epilepsy in patients with central nervous system tumors. Curr Opin Neurol. 1996;9:424.

[68] Wolf H.K., Roos D., Blumcke I., Pietsch T., Wiestler O.D. Perilesional neurochemical changes in focal epilepsies. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 1996;91:376.

[69] Flyger G. Epilepsy following radical removal of parasagittal and convexity meningiomas. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand. 1956;31:245.

[70] Foy P.M., Copeland G.P., Shaw M.D. The incidence of postoperative seizures. Acta Neurochir. 1981;55:253.

[71] Chozick B.S., Reinert S.E., Greenblatt S.H. Incidence of seizures after surgery for supratentorial meningiomas: a modern analysis. J Neurosurg. 1996;84(3):382.

[72] Rothoerl R.D., Bernreuther D., Woertgen C., Brawanski A. The value of routine electroencephalographic recordings in predicting postoperative seizures associated with meningioma surgery. Neurosurg Rev. 2003;26(2):108.

[73] Moots P.L., Maciunas R.J., Eisert D.R., Parker R.A., Laporte K., Abou-Khalil B. The course of seizure disorders in patients with malignant gliomas. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:717.

[74] Lieu A.S., Howng S.L. Intracranial meningiomas and epilepsy: incidence, prognosis and influencing factors. Epilepsy Res. 2000;38(1):45.

[75] Glantz M.J., Cole B.F., Forsyth P.A., Recht L.D., Wen P.Y., Chamberlain M.C., et al. Practice parameter: anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;54(10):1886.

[76] Vecht C.J., van Bremen M. Optimizing therapy of seizures in patients with brain tumors. Neurology. 2006;67(Suppl. 4):S10.

[77] Engel J., Pedley T.A. Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

[78] Schaller B., Rüegg S.J. Brain tumor and seizures: pathophysiology and its implications for treatment revisited. [published retraction appears in Epilepsia 44:1463, 2003]. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1223.

[79] Hildebrand J. Management of epileptic seizures. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16(4):314.

[80] Vecht C.J., Wagner G.L., Wilms E.B. Interactions between antiepileptic and chemotherapeutic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(7):404.

[81] van Breemen M.S., Vecht C.J. Optimal seizure management in brain tumor patients. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005;5(3):207.

[82] Sirven J.I., Wingerchuk D.M., Drazkowski J.F., Lyons M.K., Zimmerman R.S. Seizure prophylaxis in patients with brain tumors: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1489.

[83] Vecht C.J., Wagner G.L., Wilms E.B. Treating seizures in patients with brain tumors: Drug interactions between antiepileptic and chemotherapeutic agents. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(6 Suppl. 19):49.

[84] Wen P.Y., Marks P.W. Medical management of patients with brain tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:199.

[85] Brell M., Villà S., Teixidor P., Lucas A., Ferrán E., Marín S., et al. Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy in the treatment of exclusive cavernous sinus meningioma: functional outcome, local control, and tolerance. Surg Neurol. 2006;65(1):28.

[86] Kondziolka D., Flickinger J.C., Perez B., et al. Judicious resection and/or radiosurgery for parasagittal meningiomas: outcomes from a multicenter review. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:405.

[87] Pamir M.N., Kiliç T., Bayrakli F., Peker S. Changing treatment strategy of cavernous sinus meningiomas: experience of a single institution. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(Suppl. 2):S58.

[88] Pamir M.N., Peker S., Kilic T., Sengoz M. Efficacy of gamma-knife surgery for treating meningiomas that involve the superior sagittal sinus. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2007;68(2):73.