SECTION III CLINICAL PRESENTATION, ANATOMICAL CONCEPTS AND DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

HEADACHE – GENERAL PRINCIPLES

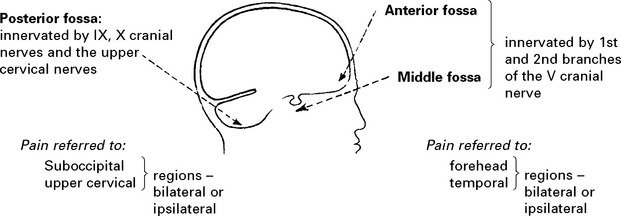

Intracranial pain-sensitive structures are:

venous sinuses, cortical veins, basal arteries, dura of anterior, middle and posterior fossae.

Extracranial pain-sensitive structures are:

Estimated prevalence of headache in the general population

| Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Tension type headache | 50–70 |

| Migraine | 10–15 |

| Medication overuse headache | 4 |

| Cluster headache | 0.1 |

| Raised intracranial pressure | < 0.01 |

HEADACHE – DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

History: most information is derived from determining:

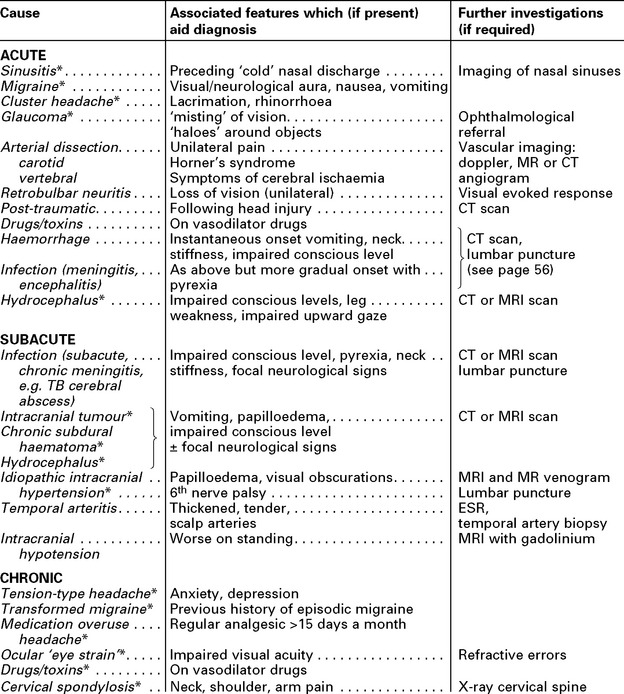

The following table classifies causes in these categories:

HEADACHE – SPECIFIC CAUSES

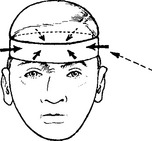

TENSION TYPE HEADACHE

Frequency: Infrequent or daily; worse towards the end of the day. May persist over many years.

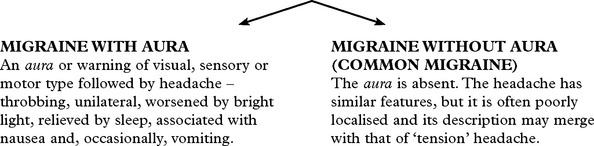

MIGRAINE

Migraine is a common, often familial disorder characterised by unilateral throbbing headache.

Onset: Childhood or early adult life.

Incidence: Affects 5–10% of the population.

Family history: Obtained in 70% of all sufferers.

Specific diagnostic criteria are required for migraine with and without aura.

Management

POST-TRAUMATIC HEADACHE

CLUSTER HEADACHES (Histamine cephalgia or migrainous neuralgia)

GIANT CELL (TEMPORAL) ARTERITIS

Neurological symptoms: strokes, hearing loss, myelopathy and neuropathy.

Visual symptoms are common with blindness (transient or permanent) or diplopia.

Duration: the headache is intractable, lasting until treated.

HEADACHE FROM RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

| Characteristics: | Associated features: |

|---|---|

HEADACHE DUE TO INTRACRANIAL HAEMORRHAGE

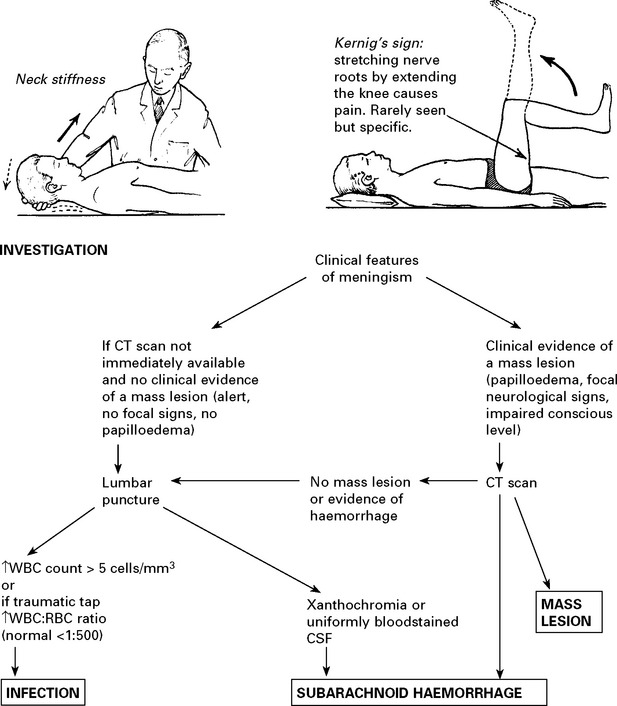

Management: further investigation – CT scan/lumbar puncture (see Meningism, page 75).

N.B. Consider sudden severe headaches to be due to subarachnoid haemorrhage until proved otherwise.

NON-NEUROLOGICAL CAUSES OF HEADACHE

Sinuses: Well localised. Worse in morning. Affected by posture, e.g. bending.

X-ray – sinus opacified. Treatment – decongestants or drainage.

Ocular: Refraction errors may result in ‘muscle contraction’ headaches

– resolves when corrected with glasses.

Dental disease: Discomfort localised to teeth. Check for malocclusion.

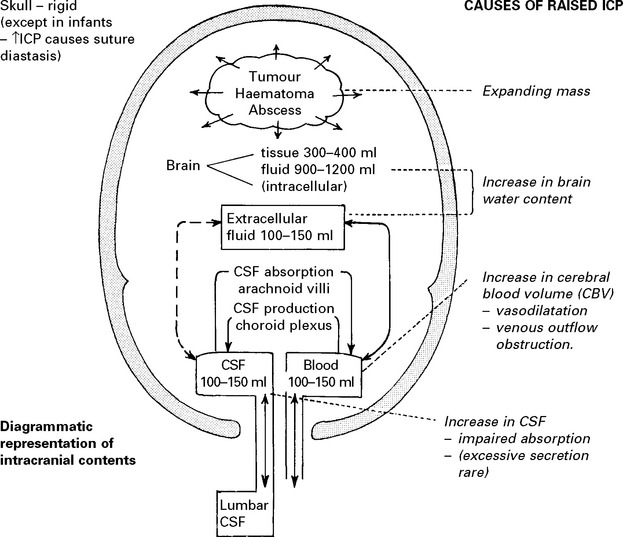

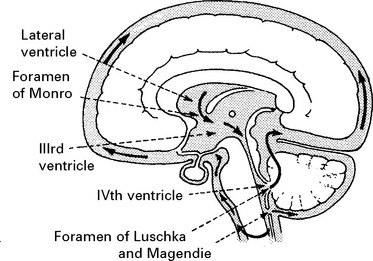

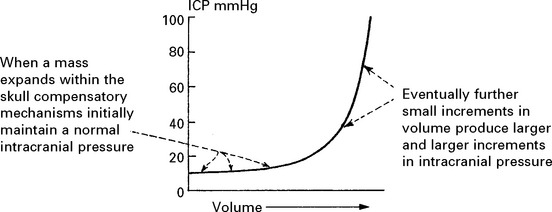

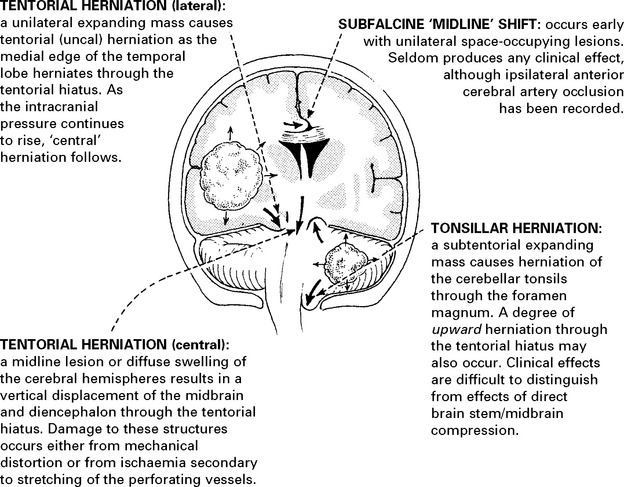

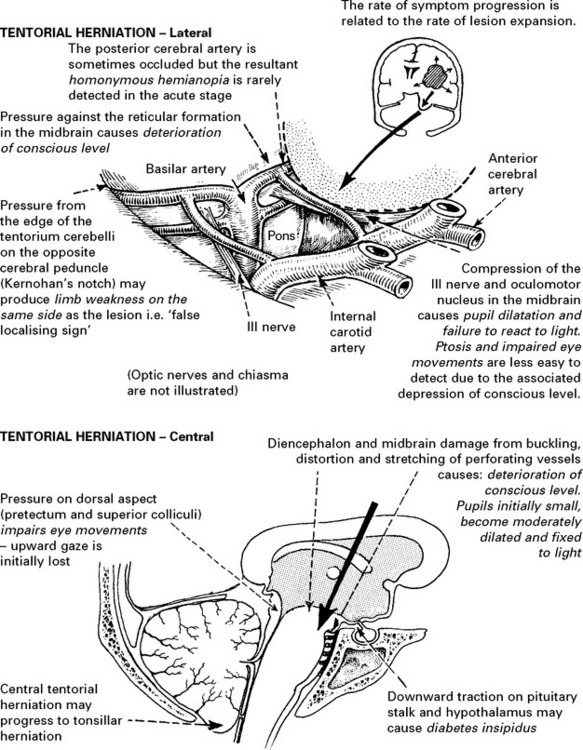

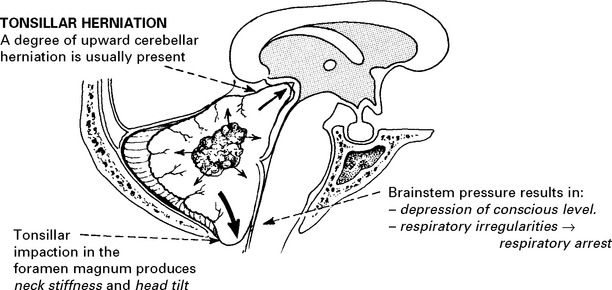

RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

Compensatory mechanisms for an expanding intracranial mass lesion:

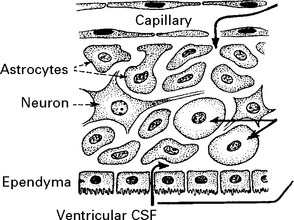

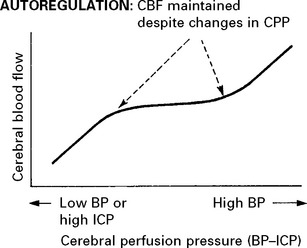

CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW (CBF)/CEREBRAL BLOOD VOLUME (CBV)

Blood flow is dependent on blood pressure and the vascular resistance:

Inside the skull, intracranial pressure must be taken into account:

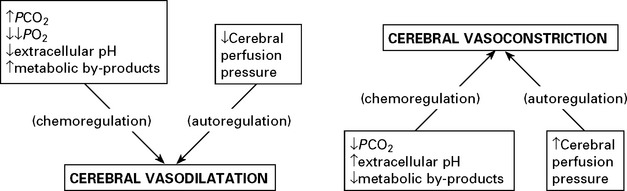

FACTORS AFFECTING THE CEREBRAL VASCULATURE

Chemoregulation

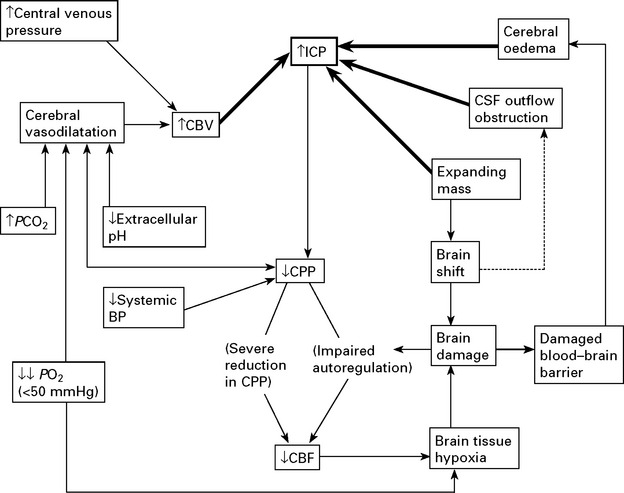

INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE (ICP)

When intracranial pressure is monitored with a ventricular catheter, regular waves due to pulse and respiratory effects are recorded (page 53). As an intracranial mass expands and as the compensatory reserves diminish, transient pressure elevations (pressure waves) are superimposed. These become more frequent and more prominent as the mean pressure rises.

CLINICAL EFFECTS OF RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

Clinical features due to ↑ICP:

INVESTIGATIONS

Patients with suspected raised intracranial pressure require an urgent CT/MRI scan. Intracranial pressure monitoring where appropriate (see page 53).

TREATMENT OF RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

In some patients, despite the above measures, cerebral swelling may produce a marked increase in intracranial pressure. This may follow removal of a tumour or haematoma or may complicate a diffuse head injury. Artificial methods of lowering intracranial pressure may prevent brain damage and death from brain shift, but some methods lead to reduced cerebral blood flow, which in itself may cause brain damage (see page 84).

Intracranial pressure is monitored with a ventricular catheter or surface pressure recording device (see page 52). Treatment may be instituted when the mean ICP is > 25 mmHg. Ensure cause is not due to constriction of neck veins.

Methods of reducing intracranial pressure

Controlled hyperventilation: Bringing the PCO2 down to 3.5kPa by hyperventilating the sedated or paralysed patient causes vasoconstriction. Although this reduces intracranial pressure, the resultant reduction in cerebral blood flow may aggravate ischaemic brain damage and do more harm than good (see page 232). Maintaining the blood pressure and the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) (>60 mmHg) appears to be as important as lowering intracranial pressure.

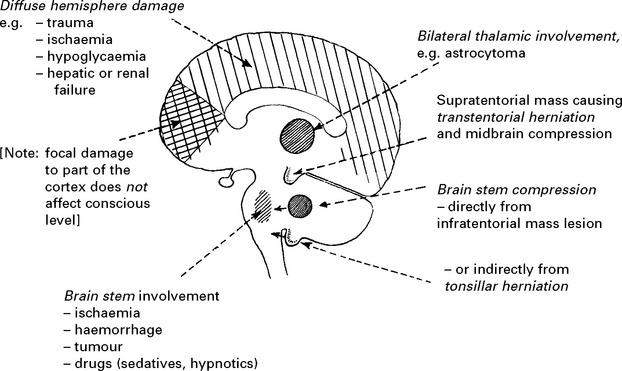

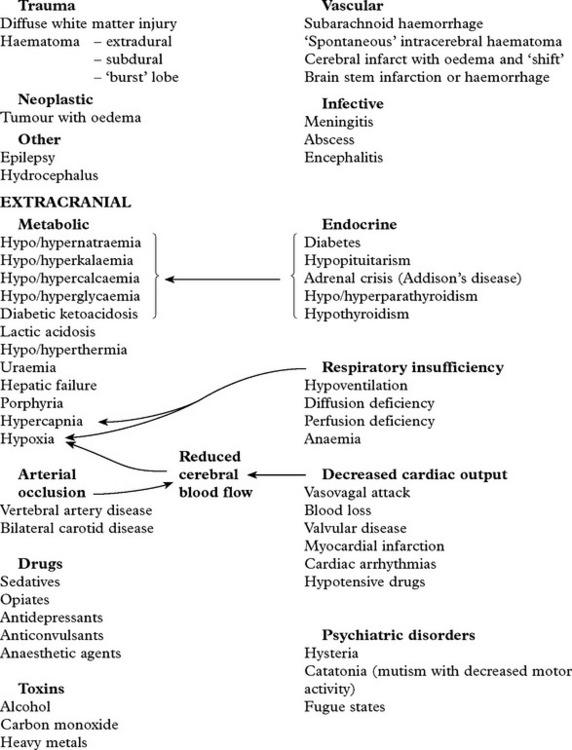

COMA AND IMPAIRED CONSCIOUS LEVEL

Many pathological processes may impair conscious level and numerous terms have been employed to describe the various clinical states which result, including obtundation, stupor, semicoma and deep-coma. These terms result in ambiguity and inconsistency when used by different observers. Recording conscious level with the Glasgow coma scale (page 5) avoids these difficulties and clearly describes the level of arousal. With this scale:

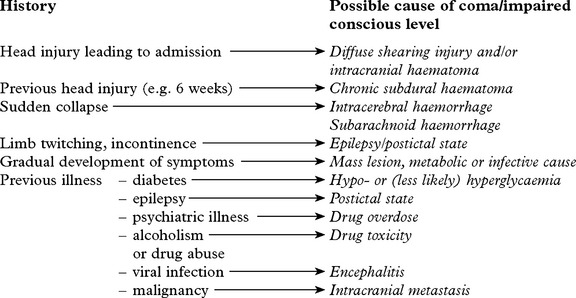

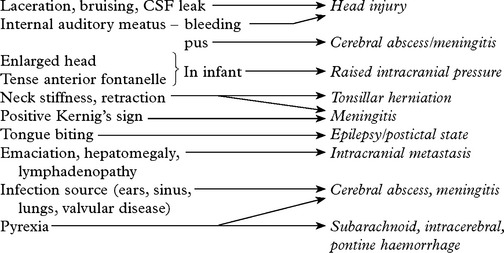

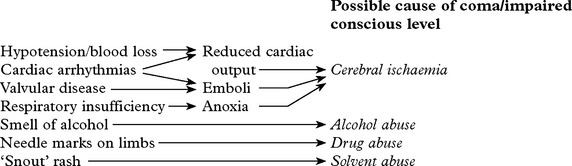

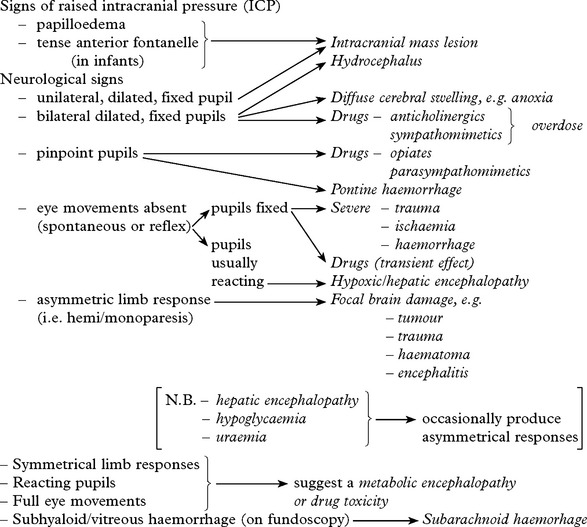

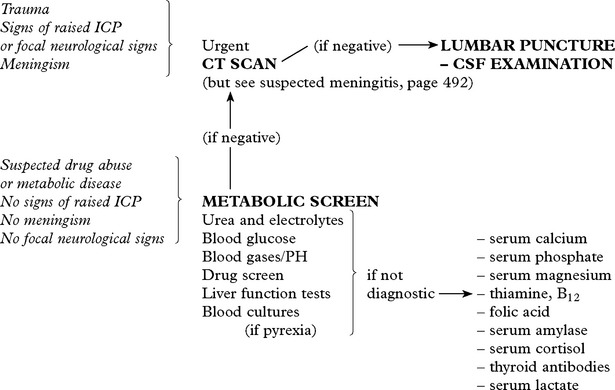

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

In addition

CHEST X-RAY – may reveal a bronchial carcinoma.

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY – may provide evidence of – subclinical epilepsy

Prognosis

Although conscious level examination does not aid diagnosis, it plays an essential role in patient management and along with the duration of coma, pupil response and eye movements provides valuable prognostic information. Non-traumatic coma tends to carry a better prognosis (see page 214).

TRANSIENT LOSS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Pseudo-seizure (non-epileptic attack disorder) – see below

Acute toxic or metabolic coma:

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

History

Try to obtain a history from eye-witness as well as from the patient themselves.

Recovery: a rapid recovery suggest syncope; waking in the ambulance suggest seizure.

History from witness (find them; phone them):

Any colour change; ‘ashen’ suggests syncope; cyanosed suggests seizure.

How quickly they recovered; rapid recovery suggest syncope.

Investigation is directed by the clinical history:

Electroencephalography (EEG) may reveal a focal or generalized disturbance – epilepsy.

Electrocardiography (ECG) and 24 hour ECG may reveal a cardiac arrythmia.

Head up tilt-table testing may reveal neurocardiogenic syncope or orthostatic hypotension.

Echocardiography may reveal cardiomyopathy.

Blood glucose may indicate hypoglycaemia.

EEG telemetry is occassionally needed.

Often attacks of unconsciousness remain unexplained and possibly have a psychological basis. The circumstances of the attack (e.g. during an argument), the non-stereotyped nature of the episode suggest a non-organic explanation. Such attacks are often mistaken for a seizure and are referred to as pseudo-seizures or non-epileptic attacks (see page 99).

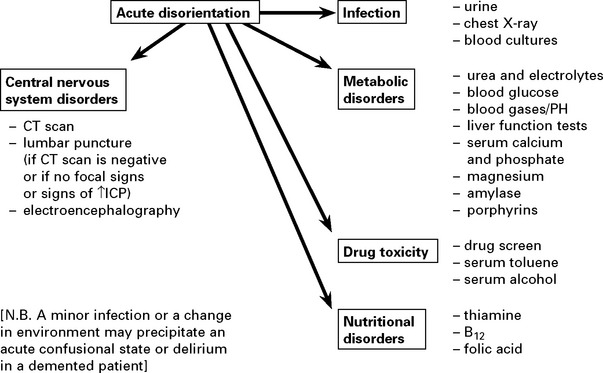

CONFUSIONAL STATES AND DELIRIUM

The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is used to confirm delirium.

The presence of features 1 and 2 and either 3 or 4 are diagnostic.

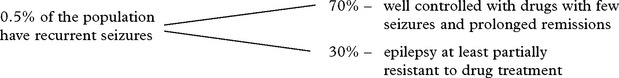

EPILEPSY

Definitions

The prodrome refers to mood or behavioural changes which may precede the attack by some hours.

The ictus refers to the attack or seizure itself.

The stereotyped and uncontrollable nature of the attack is characteristic of epilepsy.

SEIZURE CLASSIFICATION

The classification of epilepsy involves two steps:

CLASSIFICATION OF SEIZURE TYPE

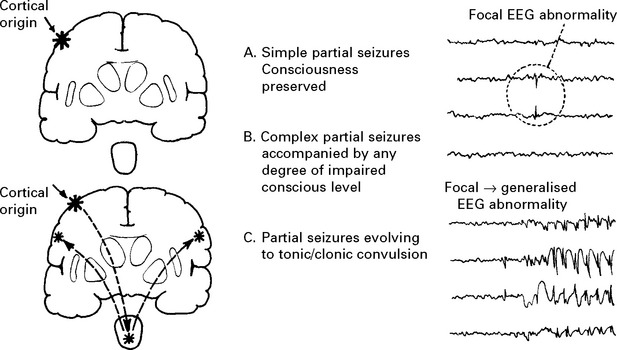

1. PARTIAL (focal, localisation related) SEIZURE

Classified by site of onset (frontal, temporal, parietal or occipital lobe) and by severity:

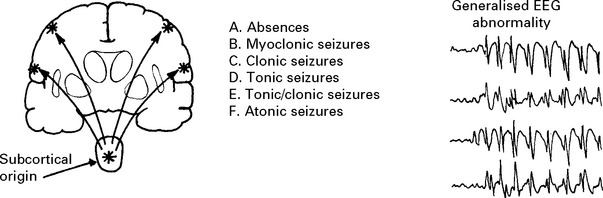

2. GENERALISED SEIZURES (convulsive or non-convulsive)

3. UNCLASSIFIED SEIZURES, There may be insufficient information to classify a seizure.

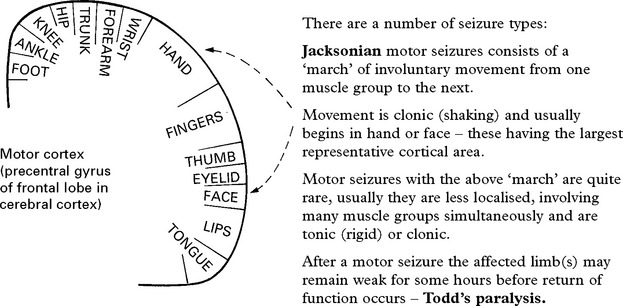

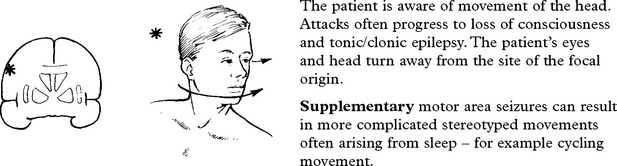

THE PARTIAL SEIZURES

Partial seizures are classified according to both their:

Severity – simple; complex partial; evolving to tonic/clonic convulsion

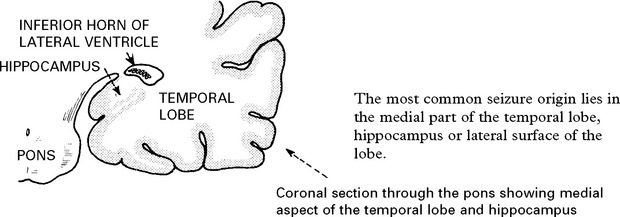

TEMPORAL LOBE SEIZURES

The nature of the attack

The content of attacks may vary in an individual patient. Commonly encountered symptoms include:

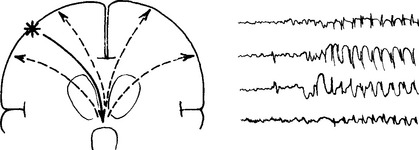

PARTIAL SEIZURES EVOLVING TO TONIC/CLONIC CONVULSION

An eyewitness account is important because retrograde amnesia may prevent recall of the onset.

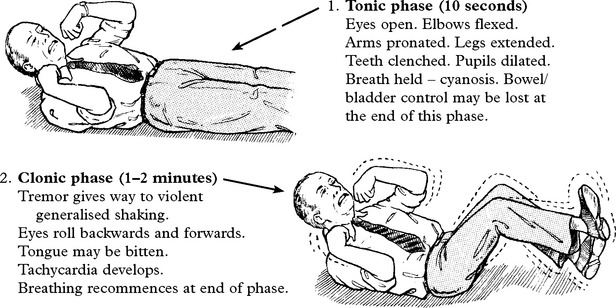

GENERALISED SEIZURES

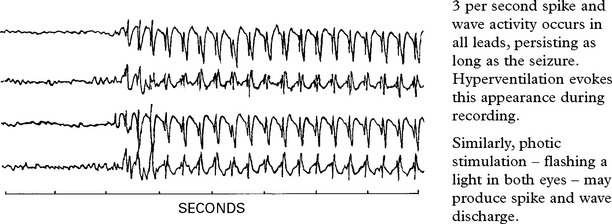

ABSENCE STATUS

Long periods of clouding of consciousness with continuing ‘spike and wave’ activity on the EEG.

MYOCLONIC SEIZURES

Sudden, brief, generalised muscle contractions. They often occur in the morning and are occasionally associated with tonic/clonic seizures. The commonest disorder is benign juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) with onset after puberty. Myoclonus on the edge of sleep is normal. Myoclonus also occurs in degenerative and metabolic disease (see page 190).

SYMPTOMATIC SEIZURES

| Newborn | Infancy and Childhood | Adult |

|---|---|---|

| Asphyxia | Febrile convulsions | Trauma |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | CNS infection | Drugs and alcohol |

| Hypocalcaemia | Trauma | CNS infection |

| Hypoglycaemia | Congenital defects | Intracranial haemorrhage |

| Hyperbilirubinaemia | Inborn errors of metabolism | Tumours |

| Water intoxication | Tumours | Vascular disease |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | Hypoglycaemia |

SEIZURES – DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

EPISODIC CONFUSION

Intermittent confusional episodes caused by drugs (e.g. barbiturates) or toxins (e.g. solvents).

PANIC ATTACKS Hyperventilation can induce focal motor and sensory symptoms.

EPILEPSY – CLASSIFICATION

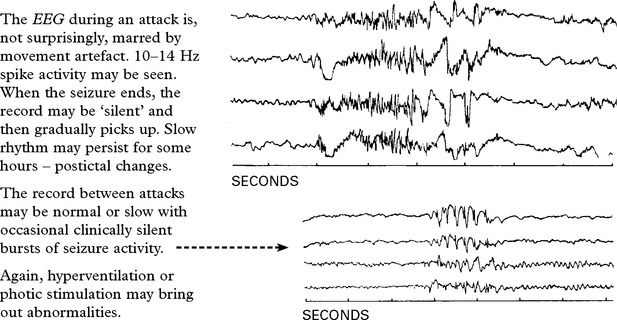

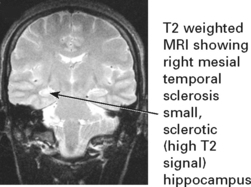

EPILEPSY – INVESTIGATION

Investigations are directed at:

The relative emphasis of these elements will depend on the clinical situation.

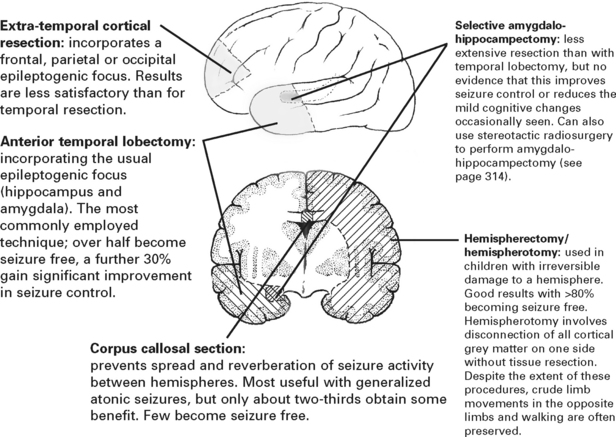

EPILEPSY – TREATMENT

EPILEPSY – SPECIFIC ISSUES

WITHDRAWAL OF DRUG TREATMENT

Several factors increase the likelihood of relapse of epilepsy after drug withdrawal:

SUDDEN UNEXPLAINED DEATH IN EPILEPSY (SUDEP)

DRIVING AND EPILEPSY (DVLA UK regulations for type 1 licence (cars))

| Off treatment | Isolated (single) seizure: 1 year off driving; if MRI and EEG are normal DVLA will consider reducing this to 6 months. |

| Withdrawal of treatment: 6 months off driving (excluding period of drug withdrawal) | |

| On treatment | Patients must be free of attacks (whilst awake) for 1 year |

| Patients must be free of attacks whilst asleep for 1 year unless they have a 3 year history of sleep related attacks alone. |

STATUS EPILEPTICUS

TREATMENT

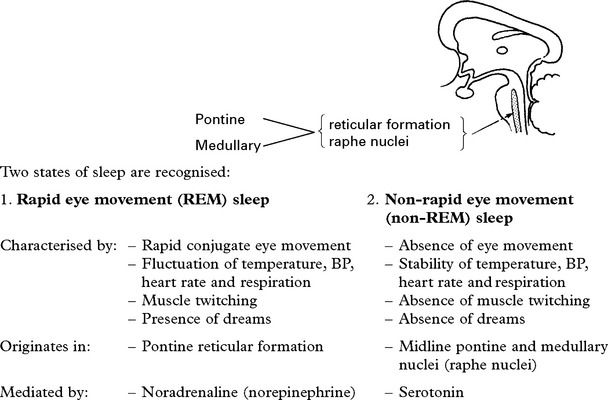

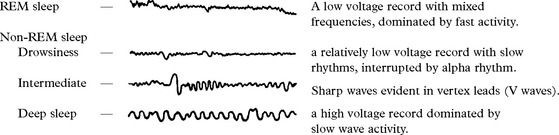

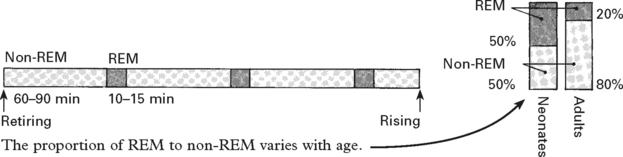

DISORDERS OF SLEEP

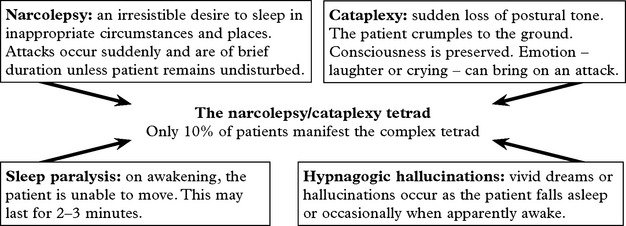

NARCOLEPSY AND CATAPLEXY

SLEEP APNOEA SYNDROMES

| Central causes: | Mechanical causes: |

|---|---|

| Brain stem medullary infarction or following cervical/foramen magnum surgery. | Obesity. Tonsillar enlargement. |

| Myxoedema. Acromegaly. |

When breathing ceases, the resultant hypercapnia and hypoxia eventually stimulate respiration.

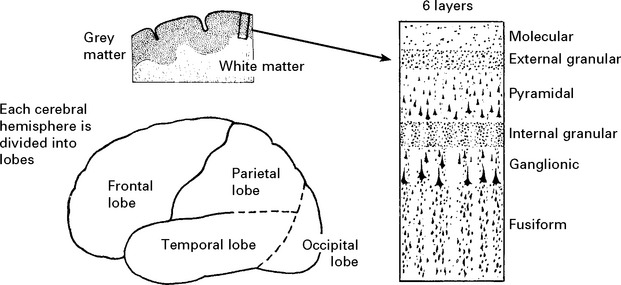

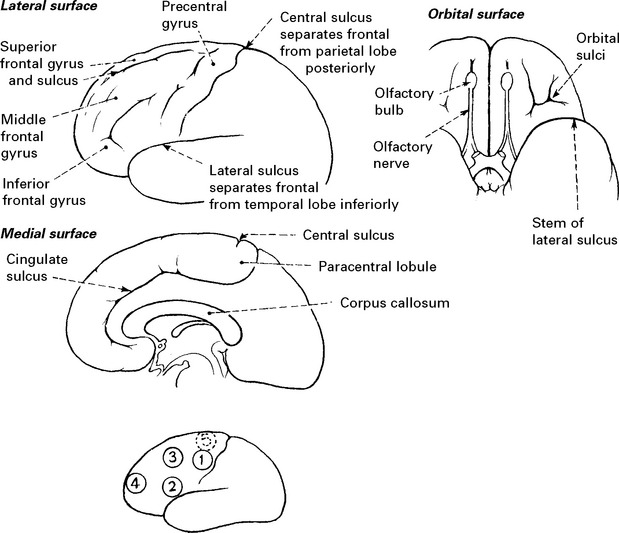

HIGHER CORTICAL DYSFUNCTION

GENERAL ANATOMY

The parietal sensory cortex, dominated by granular layers, is termed the GRANULAR CORTEX.

FRONTAL LOBES

IMPAIRMENT OF FRONTAL LOBE FUNCTION

| Orbitofrontal syndrome | Frontal convexity syndrome | Medial frontal syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Disinhibition | Apathy | Akinetic |

| Poor judgement | Indifference | Incontinent |

| Emotional lability | Poor abstract thought | Sparse verbal output |

Pre-frontal lesions are also associated with: