Clinical practice

Red cell transfusion

Two questions need to be answered before transfusion of red cells is undertaken:

Some general indications for red cell transfusion are listed in Table 42.1.

Table 42.1

Practicalities of red cell transfusion

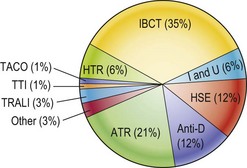

All those involved in the prescription and administration of blood should follow local guidelines with respect to patient identification and the checking of the compatibility and viability of the transfused units. Critical information is contained on the blood bag and the attached compatibility label (Fig 42.1). No discrepancies are permissible. Most serious adverse transfusion reactions are due to transfusion of the wrong blood to the patient (Fig 42.2). Errors can be reduced by newer technologies such as bar coding and radiofrequency chips – these generally rely on machine readable data on patient wristbands.

Fig 42.2 Serious hazards of transfusion, United Kingdom 1992–2010 (data with permission of SHOT).

IBCT, incorrect blood transfused; ATR, acute transfusion reactions; HSE, handling and storage errors; I and U, inappropriate/unnecessary/delayed transfusions; HTR, haemolytic transfusion reactions; TRALI, transfusion-related acute lung injury; TACO, transfusion-associated circulation overload; TTI, transfusion-transmitted infections.

Transfusion of plasma and plasma products

A wide range of plasma products is available for therapeutic use:

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP). Plasma is collected from whole blood or derived from plasmapheresis prior to rapid freezing. FFP contains the full range of coagulation factors and indications for use are shown in Table 42.2. The normal dose in an adult is one litre. FFP can transmit infection and cause immunological reactions – it is not suitable for volume expansion alone.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP). Plasma is collected from whole blood or derived from plasmapheresis prior to rapid freezing. FFP contains the full range of coagulation factors and indications for use are shown in Table 42.2. The normal dose in an adult is one litre. FFP can transmit infection and cause immunological reactions – it is not suitable for volume expansion alone.

Table 42.2

Possible indications for use of fresh frozen plasma

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

Severe liver disease (e.g. prior to liver biopsy)

Coagulopathy of massive blood transfusion

Replacement therapy of some rare congenital factor deficiencies

Bleeding in haemorrhagic disease of newborn/malabsorption vitamin K

Cryoprecipitate. This is prepared from FFP by slow thawing and separation of the resultant precipitate. It is rich in fibrinogen and may be useful in the treatment of DIC and management of massive blood transfusion.

Cryoprecipitate. This is prepared from FFP by slow thawing and separation of the resultant precipitate. It is rich in fibrinogen and may be useful in the treatment of DIC and management of massive blood transfusion.

Factor VIII and IX concentrate. See pages 72–73.

Factor VIII and IX concentrate. See pages 72–73.

Albumin. This is produced by fractionation of pooled plasma. Solutions for clinical use include human albumin 4.5/5%, human albumin 20% and plasma protein fraction (PPF). Albumin solutions are used for the treatment of severe hypoproteinaemia, particularly when associated with a low plasma volume. Concentrated solutions can help produce a diuresis in hypo-albuminaemia (e.g. in hepatic cirrhosis).

Albumin. This is produced by fractionation of pooled plasma. Solutions for clinical use include human albumin 4.5/5%, human albumin 20% and plasma protein fraction (PPF). Albumin solutions are used for the treatment of severe hypoproteinaemia, particularly when associated with a low plasma volume. Concentrated solutions can help produce a diuresis in hypo-albuminaemia (e.g. in hepatic cirrhosis).

Immunoglobulins. These can be ‘specific’ and used in passive prophylaxis against a range of infections (e.g. varicella zoster, tetanus) or to prevent haemolytic disease of the newborn (anti-Rhesus D). ‘Non-specific’ immunoglobulins are used for passive prophylaxis against hepatitis A, treatment of hypogammaglobulinaemia and in selected autoimmune disorders (e.g. ITP).

Immunoglobulins. These can be ‘specific’ and used in passive prophylaxis against a range of infections (e.g. varicella zoster, tetanus) or to prevent haemolytic disease of the newborn (anti-Rhesus D). ‘Non-specific’ immunoglobulins are used for passive prophylaxis against hepatitis A, treatment of hypogammaglobulinaemia and in selected autoimmune disorders (e.g. ITP).