1 Clinical pharmacy process

Clinical pharmacy, unlike the discipline of pharmacy, is a comparatively recent and variably implemented form of practice. It encourages pharmacists and support staff to shift their focus from a solely product-oriented role towards more direct engagement with patients and the problems they encounter with medicines. Over the past 20 years there has been an emerging consensus that the practice of clinical pharmacy itself should grow from a collection of patient-related functions to a process in which all actions are undertaken with the intention of achieving explicit outcomes for the patient. In doing so, clinical pharmacy moves to embrace the philosophy of pharmaceutical care (Hepler and Strand, 1990).

Development of clinical practice in pharmacy

The emergence of clinical pharmacy as a form of practice has been attributed to the poor medicines control systems that existed in hospitals during the early 1960s (Cousins and Luscombe, 1995). Although provoked by similar hospital-centred problems, the nature of the professional response differed between the USA and the UK.

Medication safety may have been the spur but clinical pharmacy in the 1980s grew because of its ability to promote cost-effective medicines used in hospitals. This role was recognised by the UK government, which, in 1988, endorsed the implementation of clinical pharmacy services to secure value for money from medicines. Awareness that support depended, to an extent, on the quantification of actions and cost savings led several groups to develop ways of measuring pharmacists’ clinical interventions. Coding systems were necessary to aggregate large amounts of data in a reliable manner and many of these drew upon the eight steps (Table 1.1) of the drug use process (DUP) indicators (Hutchinson et al., 1986).

| DUP stage | Action |

|---|---|

| Need for a drug | Ensure there is an appropriate indication for each drug and that all medical problems are addressed therapeutically |

| Select drug | Select and recommend the most appropriate drug based upon the ability to reach therapeutic goals, with consideration of patient variables, formulary status and cost of therapy |

| Select regimen | Select the most appropriate drug regimen for accomplishing the desired therapeutic goals at the least cost without diminishing effectiveness or causing toxicity |

| Provide drug | Facilitate the dispensing and supply process so that drugs are accurately prepared, dispensed in ready-to-administer form and delivered to the patient on a timely basis |

| Drug administration | Ensure that appropriate devices and techniques are used for drug administration |

| Monitor drug therapy | Monitor drug therapy for effectiveness or adverse effects in order to determine whether to maintain, modify or discontinue |

| Counsel patient | Counsel and educate the patient or caregiver about the patient’s therapy to ensure proper use of medicines |

| Evaluate effectiveness | Evaluate the effectiveness of the patient’s drug therapy by reviewing all the previous steps of the drug use process and taking appropriate steps to ensure that the therapeutic goals are achieved |

The data collected from these early studies revealed that interventions had very high physician acceptance rates, were made most commonly at the ‘select regimen’ and ‘need for drug’ stages of the DUP, and were influenced by hospital ward type (intensive care and paediatrics having the highest rates), pharmacist grade (rates increasing with grade) and time spent on wards (Barber et al., 1997).

Pharmaceutical care

The need to focus on outcomes of medicines use rather than dwelling only on the functions of clinical pharmacy became apparent (Hepler and Strand, 1990). The launch of pharmaceutical care as the ‘responsible provision of drug therapy for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes that improve a patient’s quality of life’ was a landmark in the topography of pharmacy practice. In reality, this was an incremental step forward, rather than a revolutionary leap, since the foundations of pharmaceutical care as ‘the determination of drug needs for a given individual and the provision not only of the drug required but also the necessary services to assure optimally safe and effective therapy’ had been established previously (Brodie et al., 1980).

The delivery of pharmaceutical care is dependent on the practice of clinical pharmacy but the key feature of care is that the practitioner takes responsibility for a patient’s drug-related needs and is held accountable for that commitment. None of the definitions of pharmaceutical care is limited by reference to a specific professional group. Although pharmacists and pharmacy support staff would expect to, and clearly can, play a central role in pharmaceutical care, it is essentially a co-operative system that embraces the contribution of other professionals and patients (Table 1.2). The avoidance of factionalism has enabled pharmaceutical care to permeate community pharmacy, particularly in Europe, in a way that clinical pharmacy and its bedside connotations did not. It also anticipated health care policy in which certain functions, such as the prescribing of medicines, have been extended beyond their traditional professional origins to be undertaken by those trained and identified to be competent to do so.

Table 1.2 Definitions of clinical pharmacy, pharmaceutical care and medicines management

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Clinical pharmacy | Clinical pharmacy comprises a set of functions that promote the safe, effective and economic use of medicines for individual patients. Clinical pharmacy process requires the application of specific knowledge of pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, pharmaceutics and therapeutics to patient care |

| Pharmaceutical care | Pharmaceutical care is a co-operative, patient-centred system for achieving specific and positive patient outcomes from the responsible provision of medicines. The practice of clinical pharmacy is an essential component in the delivery of pharmaceutical care |

| Medicines management | Medicines management encompasses the way in which medicines are selected, procured, delivered, prescribed, administered and reviewed to optimise the contribution that medicines make to producing informed and desired outcomes of patient care |

Medication-related problems

When the outcome of medicines use is not optimal, a classification (Box 1.1) for identifying the underlying medication- related problem (MRP) has been proposed (Hepler and Strand, 1990). Some MRPs are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Preventable medication-related hospital admissions in the USA have a prevalence of 4.3%, indicating that gains in public health from improved medicines management would be sizeable (Winterstein et al., 2002). In the UK too, preventable medication-related morbidity has been associated with 4.3% of admissions to a medical unit. In nearly all cases, the underlying MRP was linked to prescribing, monitoring or adherence (Howard et al., 2003).

In prospective studies, up to 28% of accident and emergency department visits have been identified as medication related, of which 70% are deemed preventable (Zed, 2005). Again, the most frequently cited causes were non-adherence and inappropriate prescribing and monitoring. The cost of drug-related morbidity and mortality in the US ambulatory care (outpatient) population was estimated in 2000 to be $177 billion. Hospital admission accounted for 70% of total costs (Ernst and Grizzle, 2001). In England, adverse drug reactions (ADRs) have been identified as the cause of 6.5% of hospital admissions for patients over 16 years of age. The median bed stay with patients admitted with an ADR was 8 days representing 4% of bed capacity. The projected annual cost to the NHS was £466 million, the equivalent of seven 800-bed hospitals occupied by patients admitted with an ADR (Pirmohamed et al., 2004).

The rate for adverse drug events among hospital inpatients in the USA has been quantified as 6.5 per 100 admissions. Overall, 28% of events were judged preventable, rising to 42% of those classified as life-threatening or serious (Bates et al., 1995). The direct cost of medication errors, defined as preventable events that may cause or lead to inappropriate medicines use or harm, in NHS hospitals has been estimated to lie between £200 and £400 million per year. To this should be added the costs arising from litigation (DH, 2004).

Benefits of pharmaceutical care

The ability to demonstrate that clinical pharmacy practice improves patient outcomes is of great importance to the pharmaceutical care model. In the USA, for example, pharmacists’ participation in physician ward rounds has been shown to reduce adverse drug events by 78% and 66% in general medical (Kucukarslan et al., 2003) and intensive care settings (Leape et al., 1999), respectively. A study covering 1029 US hospitals was the first to indicate that both centrally based and patient-specific clinical pharmacy services are associated with reduced mortality rates (Bond et al., 1999). The services involved were medicines information, clinical research performed by pharmacists, active pharmacist participation in resuscitation teams and pharmacists undertaking admission medication histories.

In the UK, the focus has been also on prevention and management of medicine-related problems. Recognition that many patients either fail to benefit or experience unwanted effects from their medicines has elicited two types of response from the pharmacy profession. The first response has been to put in place, and make use of, a range of postgraduate initiatives and programmes to meet the developmental needs of pharmacists working in clinical settings. The second has been the re-engineering of pharmaceutical services to introduce schemes for medicines management at an organisational level. These have ranged from specific initiatives to target identified areas of medication risk, such as pharmacist involvement in anticoagulation services, to more general approaches where the intention is to ensure consistency of medicines use, particularly across care interfaces. Medicines reconciliation on hospital admission ensures that medicines prescribed to in-patients correspond to those that the patient was taking prior to admission. Guidance in the UK recommends that medicines reconciliation should be part of standard care and that pharmacists should be involved as soon as possible after the patient has been admitted (NICE and NPSA, 2007). Medicines reconciliation has been defined as:

Pharmaceutical consultation

Pharmaceutical care is predicated on a patient-centred approach to identifying, preventing or resolving medicine-related problems. Central to this aim is the need to establish a therapeutic relationship. This relationship must be a partnership in which the pharmacist works with the patient to resolve medication-related issues in line with the patient’s wishes, expectations and priorities. Table 1.3 summarises the three key elements of the care process (Cipolle et al., 1998). Research in chronic diseases has shown that self-management is promoted when patients more fully participate in the goal-setting and planning aspects of their care (Sevick et al., 2007). These are important aspects to consider when pharmacists consult with patients. In community pharmacy, one approach to help patients used their medicines more effectively is medicines use review (MUR). This uses the skills of pharmacists to help patients understand how their medicines should be used, why they take them and to identify any problems patients have in relation to their medicines, providing feedback to the prescriber if necessary. Two goals of MUR are to improve the adherence of patients to prescribed medicines and to reduce medicines wastage.

| Element | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Assessment | The main goal is to establish a full medication history and highlight actual and potential drug-related problems |

| Care plan | This should clearly state the goals to optimise care and the responsibilities of both the pharmacist and the patient in attaining the stated goals |

| Evaluation | This reviews progress against the stated patient outcomes |

Clinical guidance on medicines adherence emphasises the importance of patient involvement in decisions about medicines (NICE, 2009).

Recommendations include that health care professionals should:

Medicines-taking behaviour

Intentional (or deliberate) non-adherence may be due to a number of factors. Recent work in health psychology has shaped our understanding of how patients perceive health and illness and why they often decide not to take their medicines. When people receive information about illness and its treatment, it is processed in accordance with their own belief systems. Often patients’ perceptions are not in tune with the medical reality and when this occurs, taking medicines may not make sense to the individual. For example, a patient diagnosed with hypertension may view the condition as one that is caused by stress and, during periods of lower stress, may not take their prescribed medicines (Baumann and Leventhal, 1985). Consequently, a patient holding this view of hypertension may be at increased risk of experiencing an adverse outcome such as a stroke.

More recent research has shown that patient beliefs about the necessity of the prescribed medication and concerns about the potential long-term effects have a strong influence on medicines-taking behaviour (Horne, 2001). However, a patient’s beliefs about the benefits and risks of medicines are rarely explored during consultation, despite evidence of an association between non-adherence and the patient’s satisfaction with the consultation process adopted by practitioners (Ley, 1988).

Consultation process

Descriptions of pharmaceutical consultation have been confined largely to the use of mnemonics such as WWHAM, AS METTHOD and ENCORE (Box 1.2). These approaches provide the pharmacist with a rigid structure to use when questioning patients about their symptoms but, although useful, serve to make the symptom or disease the focus of the consultation rather than the patient. A common misconception is that health care professionals who possess good communication skills are also able to consult effectively with patients; this relationship will not hold if there is a failure to grasp the essential components of consultation technique. Research into patients’ perceptions of their illness and treatment has demonstrated that they are more likely to adhere to their medication regimen, and be more satisfied with the consultation, if their views about illness and treatment have been taken into account and the risks and benefits of treatment discussed. The mnemonic approach to consultation does not address adequately the complex interaction that may take place between a patient and a health care practitioner.

Box 1.2 Mnemonics used in the pharmacy consultation process

ENCORE

Undertaking a pharmaceutical consultation can be considered as a series of four interlinked phases, each with a goal and set of competencies (Table 1.4). These phases follow a problem-solving pattern, embrace relevant aspects of adherence research and attempt to involve the patient at each stage in the process. For effective consultation, the practitioner also needs to draw upon a range of communication behaviours (Box 1.3). This approach serves to integrate the agendas of both patient and pharmacist. It provides the vehicle for agreeing on the issues to be addressed and the responsibilities accepted by each party in achieving the desired outcomes.

| Element | Goal | Examples of associated competencies |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Building a therapeutic relationship | Invites patient to discuss medication or health-related issue |

| Discusses structure and purpose of consultation | ||

| Negotiates shared agenda | ||

| Data collection and problem identification | Identifying the patient’s medication-related needs | Takes a full medication history |

| Establishes patient’s understanding of their illness | ||

| Establishes patient’s understanding of the prescribed treatment | ||

| Identifies and prioritises patient’s pharmaceutical problems | ||

| Actions and solutions | Establishing an acceptable management plan with the patient | Involves patient in designing management plan |

| Tailors information to address patient’s perception of illness and treatment | ||

| Checks patient’s understanding | ||

| Refers appropriately | ||

| Closure | Negotiating safety netting strategies with the patient | Provides information to guide action when patient experiences problems with management plan |

| Provides further appointment or contact point |

The ability to consult with patients is a key process in the delivery of pharmaceutical care and consequently requires regular review and development, regardless of experience. To ensure these core skills are developed, individuals should use trigger questions to prompt reflection on their approach to consulting (Box 1.4).

Clinical pharmacy functions and knowledge

Step 1. Establishing the need for drug therapy

Step 1.1. Relevant patient details

Without background information on the patient’s health and social circumstances (Table 1.5) it is difficult to establish the existence of, or potential for, MRPs. When this information is lacking a review solely of prescribed medicines will probably be of limited value and risks making a flawed judgement on the appropriateness of therapy for that individual.

| Factor | Implications |

|---|---|

| Age | The very young and the very old are most at risk of medication-related problems. A patient’s age may indicate their likely ability to metabolise and excrete medicines and have implications for step 2 of the drug use process |

| Gender | This may alter the choice of the therapy for certain indications. It may also prompt consideration of the potential for pregnancy or breast feeding |

| Ethnic or religious background | Racially determined predispositions to intolerance or ineffectiveness should be considered with certain classes of medicines, for example, ACE inhibitors in Afro-Caribbean people. Formulations may be problematic for other groups, for example, those based on blood products for Jehovah’s Witnesses or porcine-derived products for Jewish patients |

| Social history | This may impact on ability to manage medicines and influence pharmaceutical care needs, for example, living alone or in a care home or availability of nursing, social or informal carers |

| Presenting complaint | Symptoms the patient describes and the signs identified by the doctor on examination. Pharmacists should consider whether these might be attributable to the adverse effects of prescribed or purchased medicines |

| Working diagnosis | This should enable the pharmacist to identify the classes of medicines that would be anticipated on the prescription based on current evidence |

| Previous medical history | Understanding the patient’s other medical conditions and their history helps ensure that management of the current problem does not compromise a prior condition and guides the selection of appropriate therapy by identifying potential contraindications |

| Laboratory or physical findings | The focus should be on findings that may affect therapy, such as |

Step 1.2. Medication history

Discrepancies between the history recorded by the medical team and that which the pharmacist elicits fall into two categories: intentional (where the medical team has made a decision to alter the regimen) or unintentional (where a complete record was not obtained). Discrepancies should be clarified with the prescriber or referred to a more senior pharmacist. Box 1.5 lists the key components of a medication history.

Box 1.5 Key components of a medication history

Step 2. Selecting the medicine

Step 3. Administering the medicine

Table 1.6 summarises the main pharmaceutical considerations for step 3. At this point, the practitioner needs to ensure the following tasks have been completed accurately.

Table 1.6 Pharmaceutical considerations in the administration of medicines

| Dose | Is the dose appropriate, including adjustments for particular routes or formulations? |

| Examples: differences in dose between intravenous and oral metronidazole, intramuscular and oral chlorpromazine, and digoxin tablets compared with the elixir | |

| Route | Is the prescribed route available (is the patient nil by mouth?) and appropriate for the patient? |

| Examples: unnecessary prescription of an intravenous medicine when the patient can swallow, or the use of a solid dosage form when the patient has dysphagia | |

| Dosage form | Is the medicine available in a suitable form for administration via the prescribed route? |

| Documentation | Is documentation complete? Do nurses or carers require specific information to administer the medicine safely? |

| Examples: appropriateness of crushing tablets for administration via nasogastric tubes, dilution requirements for medicines given parenterally, rates of administration and compatibilities in parenteral solutions (including syringe drivers) | |

| Devices | Are devices required, such as spacers for inhalers? |

Step 6. Patient advice and education

Although the research on adherence indicates the primacy of information that has been tailored to the individual’s needs, resources produced by national organisations, such as Diabetes UK (www.diabetes.org.uk) and British Heart Foundation (www.bhf.org.uk), may also be of help to the patient and their family or carers. In addition, patients often require specific information to support their daily routine of taking medicines. All written information, including medicines reminder charts, should be dated and include contact details of the pharmacist to encourage patients to raise further queries or seek clarification.

Step 7. Evaluating effectiveness

Case 1.1

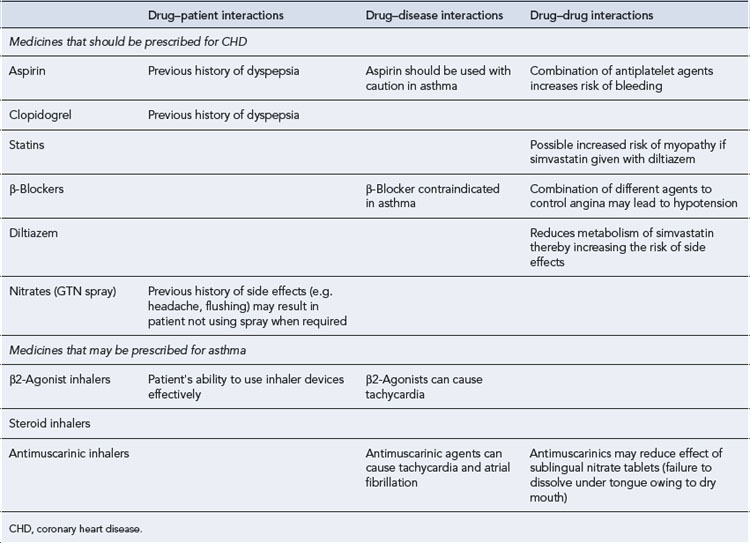

Steps 3 and 4. Administering and providing the medicines

| Recommendation | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|

| Medicines that should be prescribed for CHD | ||

| Aspirin | 75 mg daily orally after food | Benefit outweighs risk if used with PPI |

| Clopidogrel | 75 mg daily orally after food | Benefit outweighs risk if used with PPI |

| Length of course should be established in relation to previous stent | ||

| Lansoprazole | 15 mg daily orally | Decreases risk of GI bleeds with combination antiplatelets |

| Concerns about some PPIs reducing the effectiveness of clopidogrel makes selection of specific PPI important | ||

| Simvastatin | 20 mg daily orally | Low dose selected due to diltiazem reducing the metabolism of simvastatin and increasing the risk of side effect |

| Nitrates | 2 puffs sprayed under the tongue when required for chest pain | |

| Diltiazem | 90 mg m/r twice a day | Used for rate control as β-blockers contraindicated in asthma |

| Ramipril | 10 mg daily | To reduce the progression of CHD and heart failure |

| Medicines that may have been prescribed | ||

| Salbutamol inhaler | 2 puffs (200 µcg) to be inhaled when required | Patient should follow asthma treatment plan if peak flow decreases |

| Beclometasone inhalers | 2 puffs (400 µcg) twice a day | Asthma treatment plan which may include increasing the dose of inhaled steroids if peak flow decreases |

CHD, coronary heart disease; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; GI, gastro-intestinal; m/r, modified release.

Steps 5, 6 and 7. Monitoring therapy, patient education and evaluation

Table 1.9 The case of Mr JB: monitoring criteria and patient advice

| Recommendation | |

|---|---|

| Drugs that should be prescribed for CHD | |

| Aspirin | Ask patient about any symptoms of dyspepsia or worsening asthma |

| Clopidogrel | Ask patient about any symptoms of dyspepsia |

| Lansoprazole | If PPIs don’t resolve symptoms, primary care doctor should be consulted |

| Simvastatin | Liver function tests 3 months after any change in dose, or annually Creatine kinase only if presenting with symptoms of unexplained muscle pain Cholesterol levels 3 months after any change in dose, or annually if at target |

| Nitrates (GTN spray) | Frequency of use to be noted. Increasing frequency that results in a resolution of chest pain should be reported to primary care doctor and anti-anginal therapy may be increased ANY use that does not result in resolution of chest pain requires urgent medical attention |

| Diltiazem | Blood pressure and pulse monitored regularly |

| Ramipril | Renal function and blood pressure monitored within 2 weeks of any dose change, or annually |

| Drugs that may have been prescribed for asthma | |

| Salbutamol inhaler | Salbutamol use should be monitored as any increase in requirements may require increase in steroid dose |

| Beclometasone inhalers | Monitor for oral candidiasis |

Quality assurance of clinical practice

Quality assurance of clinical pharmacy has tended to focus on the review of performance indicators, such as intervention rates, or rely upon experienced pharmacists to observe and comment on the practice of others using local measures. The lack of generally agreed or national criteria raises questions about the consistency of these assessments, where they take place, and the overall standard of care provided to patients. Following the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry (2001) into paediatric cardiac surgery, there has been much greater emphasis on the need for regulation to maintain the competence of health care professionals, the importance of periodic performance appraisal coupled with continuing professional development, and the introduction of revalidation.

The challenges for pharmacists are twofold: first, to demonstrate their capabilities in a range of clinical pharmacy functions and second, to engage with continuing professional development in a meaningful way to satisfy the expectations of pharmaceutical care and maintain registration with, for example, the General Pharmaceutical Council in the UK. The pragmatic approach to practice and the clinical pharmacy process outlined throughout this chapter has been incorporated into a professional development framework, called the General Level Framework (GLF) available at: www.codeg.org, that can be used to develop skills, knowledge and other attributes irrespective of the setting of the pharmacist and their patients.

Barber N.D., Batty R., Ridout D.A. Predicting the rate of physician-accepted interventions by hospital pharmacists in the United Kingdom. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm.. 1997;54:397-405.

Bates D.W., Cullen D.J., Laird N., et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 1995;274:29-34.

Baumann L.J., Leventhal H. I can tell when my blood pressure is up, can’t I? Health Psychol.. 1985;4:203-218.

Bond C.A., Raehl C.L., Franke T. Clinical pharmacy services and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:556-564.

Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry. The Report of the Public Inquiry into Children’s Heart Surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995. In Learning from Bristol. London: Stationery Office; 2001. Available at: http://www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk/final_report/rpt_print.htm

Brodie D.C., Parish P.A., Poston J.W. Societal needs for drugs and drug related services. Am. J. Pharm. Educ.. 1980;44:276-278.

Cipolle R.J., Strand L.M., Morley P.C., editors. Pharmaceutical Care Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

Cousins D.H., Luscombe D.K. Forces for change and the evolution of clinical pharmacy practice. Pharm. J.. 1995;255:771-776.

Department of Health. Building a Safer NHS for Patients: Improving Medication Safety. London: Department of Health, 2004. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4071443

Ernst F.R., Grizzle A.J. Drug-related morbidity and mortality: updating the cost of illness model. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc.. 2001;41:192-199.

Hepler C.D., Strand L.M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm.. 1990;47:533-543.

Horne R. Compliance, adherence and concordance. In: Taylor K., Harding G., editors. Pharmacy Practice. London: Taylor and Francis, 2001.

Howard R.L., Avery A.J., Howard P.D., et al. Investigation into the reasons for preventable drug related admissions to a medical admissions unit: observational study. Qual. Saf. Health Care. 2003;12:280-285.

Hutchinson R.A., Vogel D.P., Witte K.W. A model for inpatient clinical pharmacy practice and reimbursement. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm.. 1986;20:989-992.

Kucukarslan S.N., Peters M., Mlynarek M., et al. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch. Intern. Med.. 2003;163:2014-2018.

Leape L.L., Cullen D.J., Clapp M.D., et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 1999;282:267-270.

Ley P. Communicating with Patients. In Improving Communication, Satisfaction and Compliance. London: Croom Helm; 1988.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and National Patient Safety Agency. Technical Patient Safety Solutions for Medicines Reconciliation on Admission of Adults to Hospital. London: NICE, 2007. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/PSG001GuidanceWord.doc

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. In Clinical Guideline 76. London: NICE; 2009. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG76NICEGuideline.pdf

Pirmohamed M., James S., Meakin S., et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. Br. Med. J.. 2004;329:15-19.

Sevick M.A., Trauth J.M., Ling B.S., et al. Patients with complex chronic diseases: perspectives on supporting self management. J. Gen. Intern. Med.. 2007;22:438-444.

Winterstein A.G., Sauer B.C., Helper C.D., et al. Preventable drug-related hospital admissions. Ann. Pharmacother.. 2002;36:1238-1248.

Zed P.J. Drug-related visits to the emergency department. J. Pharm. Pract.. 2005;18:329-335.