Clinical examination of the shoulder

Pain in the shoulder is, after low back pain, the most frequent complaint of orthopaedic patients. Despite the frequency of shoulder lesions – and the consequent pain and disability – much confusion still exists as to aetiology, terminology and treatment,1 in contrast to the statement made by Cyriax:2,3

On other occasions, patients present with a painful limitation of passive movement together with pain on resisted movements, and the question arises as to whether the problem is in an inert or a contractile structure. If there is capsular limitation on examination, the joint should be treated first. If resisted movements remain painful after the joint has been managed appropriately, then the tendons should be treated. This approach is the best one, because resisted movements very often become negative after arthritis has disappeared. The only explanation for the phenomenon is the close relationship between the capsule of the shoulder and the surrounding tendons.4 It can easily be understood how tension on the contractile structures may influence the pain originating in arthritis. Therefore pain on resisted movement(s) in association with an articular pattern should not be interpreted as being caused by a simple tendinosis. Of course, a severe tendinosis can limit active movement, because of the pain. But passive movements are of full range with a normal end-feel, even though there might be severe pain at the end of movement.

An arthritis is an arthritis, a tendinosis is a tendinosis and both have to be treated as such. It is a common misbelief that, as long as steroid is injected somewhere in the shoulder area, it will spread and cure the lesion, no matter where the lesion lies or where it was injected.5 In fact, if there is one region in the body which ought to be diagnosed and treated very specifically it is the shoulder. It is necessary to replace a vague diagnosis such as ‘rotator cuff disease’ or frozen shoulder by a precise one indicating exactly what is wrong.6–8

Referred pain

Pain referred to the shoulder

Other possible causes of referred pain at the shoulder are visceral disorders. The diaphragm is largely developed from the third and fourth cervical segment, the heart from the eighth cervical to the fourth thoracic. Therefore both can give rise to pain in the shoulder and arm. Irritation of the diaphragm and of the phrenic nerve, for example by blood or air under the diaphragm, is another well-known source of acute shoulder pain.9,10

A pulmonary neoplasm at the base of the lung with involvement of the diaphragm can provoke pain in the shoulder area. The same may also happen with a tumour of the superior sulcus (Pancoast’s tumour). The majority of these patients complain of shoulder pain and are often mistakenly thought to be suffering from a musculoskeletal lesion.11,12

Pain referred from the shoulder

Most structures around the shoulder are derived from the C5 segment. There is one important exception: the acromioclavicular joint, which is of C4 origin (Fig. 12.1). In acromioclavicular joint problems the pain is felt at the tip of the shoulder, with little spread. Exceptionally, when the lesion lies at the inferior acromioclavicular ligament, the pain can spread into the upper arm.

Fig 12.1 The C4 dermatome.

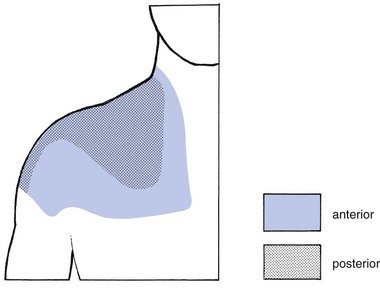

In a lesion of one of the other shoulder structures, such as in all types of tendinosis, arthritis and subdeltoid bursitis, the pain is not so much felt at the tip of the shoulder but rather starts in the deltoid region and may spread further down the radial aspect of the arm to the base of the thumb (C5 dermatome; Fig. 12.2). How far down the arm the pain is referred depends on the severity of the lesion: the more severe the inflammation, the further the pain will spread. In glenohumeral arthritis, the degree of pain reference is of particular interest in following the healing process: as the patient improves, the inflammation decreases and the pain spreads less far.

Fig 12.2 The C5 dermatome.

History

In arthritis of the shoulder, the history will be important to establish the stage (see Ch. 13). In other disorders it is of less significance.

The answers to a number of questions (summarized in Box 12.1) will be needed.

• What is your age? Age can be relevant in several disorders. It can be helpful in defining the exact type of arthritis. Traumatic arthritis will only be met after 40 years of age, arthritis from immobilization after the age of 60. Subdeltoid bursitis might be present between 15 and 65 years of age. Tendinosis can occur at any adult age.

• What is the pain and does it radiate? Pain starting in the deltoid area and spreading towards the wrist, along the radial aspect of the arm, is caused by a lesion that originates in C5. Such pain may be felt in the whole dermatome or only in part of it. The majority of the shoulder structures belong to the C5 segment. The acromioclavicular joint, a C4 structure, is the main exception. A patient who indicates the tip of the shoulder only as the site of pain suggests strongly that there is a lesion of the acromioclavicular joint. Whether the pain is caused by arthritis, bursitis or simple tendinosis will make no difference to where or how far distally the pain is felt. The distal spread of referred pain depends only on the degree of inflammation. It is routine to ask if the pain remains above the elbow or radiates below it – a matter of particular importance in arthritis.

• Is there any pain in the arm at rest? This gives information about the severity of the lesion: if spontaneous pain is present, there is a greater degree of inflammation than if pain is felt only on movement. Again, the answer to this question is one of the criteria for judging the stage of arthritis.

• Can you lie on the affected side at night? Pain when lying on the shoulder indicates more severe inflammation than just pain on exercise. Bursitis, tendinosis or arthritis may make it impossible for the patient to lie on the affected side at night. Consequently, this question is not of much help in defining the exact nature of the structure at fault. However, it is rather important in following the resolution of the disorder: as the condition improves, the pain at night diminishes and finally disappears.

• Did the pain come on spontaneously or was there any particular reason for it, such as overactivity or an injury? It is clear that overactivity may provoke tendinosis. In a ruptured tendon, however, one should not necessarily expect recent overuse. Overactivity can also cause arthritis in a joint that is already osteoarthrotic; this is just as true for the acromioclavicular joint as it is for the glenohumeral joint. In haemophilia, haemarthrosis usually comes on spontaneously; it is more common at the knee but may occur at the shoulder as well.

• For how long have you had the pain? If the pain has already been present for some months, an acute subdeltoid bursitis can be excluded because the full course of this condition is 6 weeks. In addition, onset is abrupt over a few days, sometimes only hours, as in an attack of gouty arthritis. Arm pain because of root compression by a cervical disc protrusion wears off in about 4 months. Long-standing pain can be the outcome of a chronic subdeltoid bursitis or a simple tendinosis. Both can last for years. Monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis can take up to 2 years to disappear spontaneously.

• Are any other joints affected? A more generalized inflammatory disorder is expected if other joints have been previously involved or are attacked at the same time. Indeed, the shoulder joint can be the seat of rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus and ankylosing spondylitis.

• How is your general condition? Have you had any operations? Recent unexplained loss of weight can be the first sign of a carcinoma. A primary tumour at the shoulder or metastases can be a local source of shoulder pain. A Pancoast’s tumour of the lung often provokes pain in the shoulder area.

Inspection

The inspection starts with checking what position the head is held in and whether both shoulders are level. It is important to check for redness, swelling, muscular wasting or any deformity such as scapular winging. A step deformity at the upper lateral aspect of the shoulder is caused by an acromioclavicular dislocation, with the distal end of the clavicle lying superior to the acromion. Atrophy of the upper trapezius may indicate spinal accessory nerve palsy.13 Atrophy of supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus is caused by either a supraspinous nerve palsy or long-standing rotator cuff lesions.14 Effusion of more than 10–15 mL arising from the glenohumeral joint is normally visible on inspection at the anterior centre of the humeral head. Local swelling may also be found in acute, haemorrhagic or chronic subdeltoid bursitis and in acromioclavicular joint cysts,15 as well as in tumours.

Functional examination

The shoulder is an easy joint to examine. The intention is to obtain the maximum information from a minimum number of tests. Recent studies have shown high inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of the examination scheme presented.16–18

Preliminary examination

• There is or was trapezius pain

• The pain is only at the top of the shoulder and/or at the clavipectoral area

• The pain is in the arm but remains quite localized

• The pain in the arm is influenced by movements of the neck

• Coughing, sneezing or taking a deep breath increases the pain

The preliminary examination of the upper quadrant is comprised of the following tests (Box 12.2):

1. Six active movements of the cervical spine – range of movement and/or painfulness; quick survey of the cervical spine

2. Active elevation of the shoulder girdle – range of movement and/or painfulness; quick survey of all the structures of the shoulder girdle

3. Resisted rotations of the cervical spine and resisted elevation of the scapulae; quick survey of nerve roots C1–C2–C3–C4

4. Active elevation of both arms – range and pain; quick survey of shoulder and shoulder girdle

5. Resisted movements of the upper limb – strength and pain; this is both a quick test for peripheral lesions at the elbow–arm–wrist and a neurological examination of roots C5–C6–C7–C8–T1 and of the peripheral nerves of the upper limb

6. Passive examination of the elbow; quick test of the elbow joint.

If the examination reveals that the lesion lies in the shoulder, the examiner will try to define in which particular structure the lesion is situated by carrying out a detailed shoulder examination; this is comprised of 12 basic tests (summarized in Box 12.3).

Basic functional examination of the shoulder

The basic shoulder examination consists of 12 tests. It is important always to perform every basic test and not to stop, even if the diagnosis appears clear after a limited number of tests. Stopping too soon can easily lead to an incomplete diagnosis. It is important to realize that, in mixed patterns of pain on both passive and resisted movement(s), pain on resisted movements does not exclude a disorder in an inert structure, nor pain on passive movements a disorder in a contractile structure. These results may sometimes lead to diagnostic difficulties (see Ch. 4).

Elevation of the arm

Active elevation

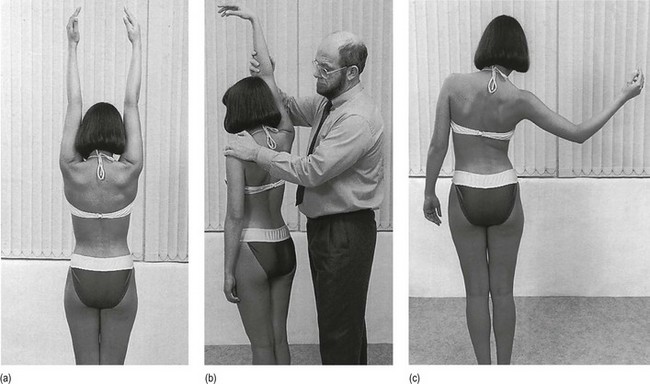

The patient is asked to raise both arms sideways above the head, as far as possible (Fig. 12.3a). The range of movement and the influences, if any, on pain are noted.

This very unselective and broad test investigates both inert and contractile structures, not only of one single joint, but also of all five ‘joints’ of the shoulder girdle (see online chapter Clinical examination of the shoulder girdle). Therefore, the result should always be interpreted in light of the other tests. As it gives a good idea of the patient’s willingness to cooperate, it will also help in identifying a person who has no genuine lesion but is feigning illness.

Passive elevation

The examiner takes the patient’s arm just proximal to the elbow, brings it upwards from the side and pushes it as far as it will go towards the head. At the same time counterpressure is applied over the contralateral shoulder, preventing the patient from side-flexing to the other side (Fig. 12.3b). Pain, range of motion and end-feel are noted. Because this movement comes to a halt when the axillary portion of the capsule is stretched, the normal end-feel is elastic.

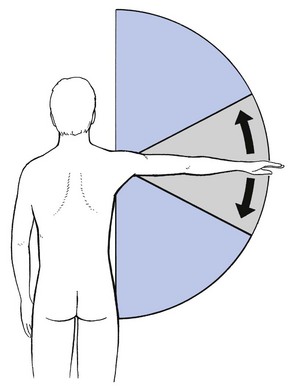

Painful arc

The patient raises the arm, actively, in a frontal plane and concentrates on pain likely to occur at mid-range, being asked to indicate where pain starts and where it stops on further elevation (Fig. 12.3c).

A painful arc is defined as the symptom appearing somewhere around the halfway mark, with the arm near the horizontal and disappearing before the end of the movement (Fig. 12.4). This description holds even if pain is again present at the end-point. Some patients have an ascending arc, others a descending one; both are regarded as a real painful arc and no diagnostic distinction is made between them. Sometimes an arc becomes visible to the examiner, i.e. when the patient avoids the painful movement by bringing the arm towards the front of the body during elevation.

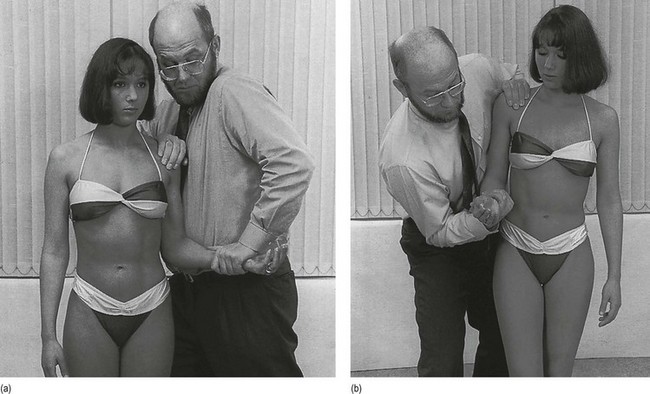

Fig 12.4 Painful arc.

Three tests for the glenohumeral joint

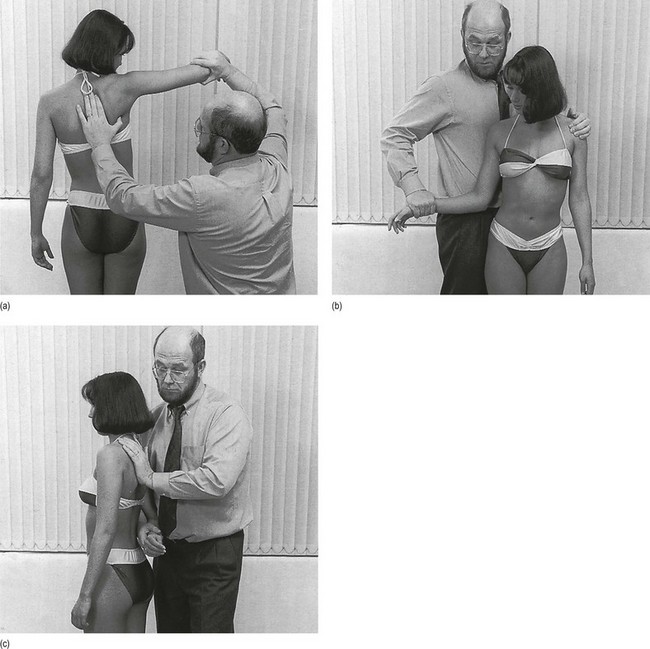

Passive scapulohumeral abduction

The lower angle of the scapula is immobilized by the thumb and index. With the other hand, the examiner takes the patient’s arm just above the elbow and lifts it up until the scapula starts to move (Fig. 12.5a). It is important for the patient not to assist this movement actively because then the scapula immediately starts to rotate, so making the movement a compound one involving several joints.

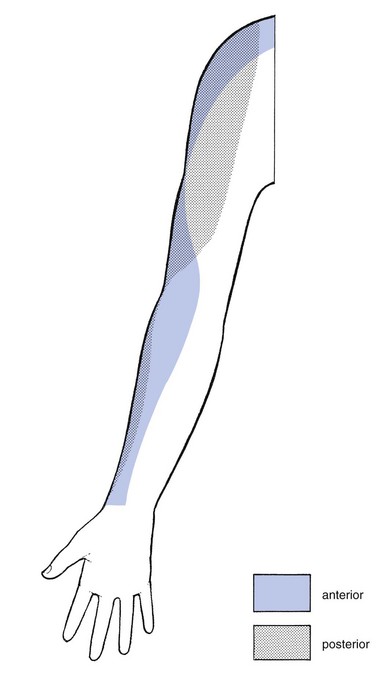

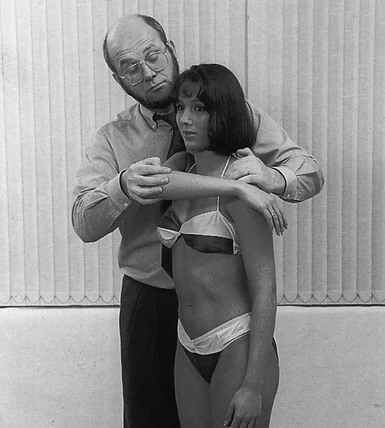

Passive lateral rotation

The examiner takes the patient’s arm above the wrist, flexes the elbow to a right angle and pulls the arm with gentle pressure into full lateral rotation, meanwhile avoiding extension by holding the patient’s elbow against the side of the abdomen. The trunk is immobilized by bringing the other hand around the patient’s contralateral shoulder (Fig. 12.5b).

Besides the anterior portion of the joint capsule, other structures, such as the subcoracoid bursa, the acromioclavicular joint and the subscapularis tendon, are tested as well. Limitation of the movement is mainly found if something is wrong with the scapulohumeral joint itself; in this event, a harder end-feel is usually present.19,20 A simple tendinosis of the subscapularis does not cause limitation of the movement but may render it very painful.

Passive medial rotation

With one hand still just above the patient’s wrist and flexing the patient’s elbow to 90°, the arm is brought into full medial rotation, without extension. The examiner’s other hand is placed dorsally between the scapulae (Fig. 12.5c). The normal amplitude is about 90°. As before, this movement should be compared on both sides.

Resisted movements

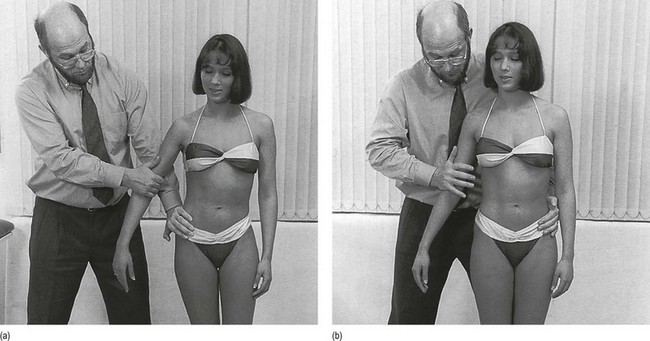

Resisted adduction

The patient is asked to pull the right arm towards the body as hard as possible. The examiner puts one hand around the elbow, and the other at the patient’s ipsilateral side (Fig. 12.6a).

Resisted abduction

The test is performed with the arm hanging down, a few degrees of abduction being permitted. The examiner asks the patient to push his or her arm to the side, meanwhile applying counterpressure at the elbow. The examiner’s other hand stabilizes the patient on the contralateral side (Fig. 12.6b).

Resisted lateral rotation

The patient is asked to bend the elbow to a right angle and to push the forearm away from the body. To avoid any movement of the trunk, the other hand is put on the patient’s contralateral shoulder (Fig. 12.7a). Counterpressure is applied just above the wrist and care must be taken to get two details right. First, the patient should keep the elbow against the body, so that there is no element of abduction. Second, extension of the elbow during lateral rotation is avoided. This is easily checked if the examiner puts the little finger underneath the patient’s wrist: extension at the elbow causes the digit to move down.

Resisted medial rotation

This is tested in the same position as resisted lateral rotation, but the patient’s arm is held at the inner part of the wrist and the forearm is pulled towards the body (Fig. 12.7b).

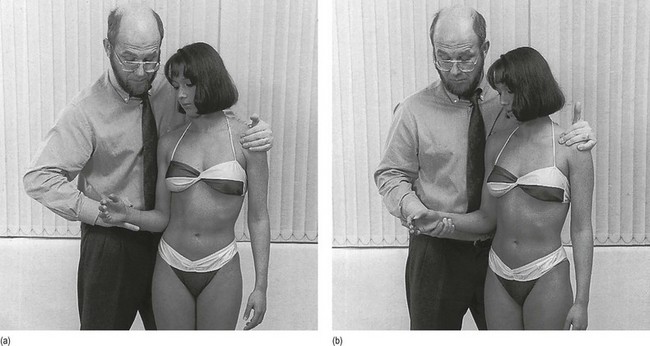

Resisted elbow flexion

With the elbow still bent at a right angle and the forearm supinated, the forearm is pulled up. Counterpressure is applied to the distal part of the forearm just above the wrist. The other hand is placed on the patient’s ipsilateral shoulder (Fig. 12.8a).

Resisted elbow extension

In the same position as for flexion, the patient attempts to extend the elbow. To be able to hold the patient’s elbow at 90° of flexion, the examiner puts his or her own elbow on the iliac crest, the arm in an almost vertical position underneath the patient’s wrist. The other hand rests on the patient’s ipsilateral shoulder (Fig. 12.8b).

Accessory tests

Sometimes the diagnosis is still not clear after the basic examination and a differential diagnosis has to be undertaken. At other times, the exact structure at fault has been identified by this stage of the examination but the precise localization of the lesion within that particular structure remains uncertain. In both cases, one or more accessory tests may be required (Box 12.4). Passive horizontal adduction is the only one which is explained here. The other tests are discussed, together with the corresponding disorders, in the following chapters.

Passive horizontal adduction

The patient’s arm is brought horizontally in front of the body. At the end of the movement the elbow is pressed gently further towards the contralateral shoulder (Fig. 12.9). Twisting of the patient’s trunk is prevented by the examiner bringing the other hand behind this shoulder.

Fig 12.9 Passive horizontal adduction.

Technical investigations

All technical investigations of the shoulder have in common the fact that they are performed to search for anatomical changes. This is in contrast with the objective of a clinical examination, which aims to detect functional deficiencies and/or pain. Anatomical changes that are not causing functional disturbances (remain asymptomatic) are very common in the shoulder region and their frequency increases with age.22–24 Therefore, one should always interpret technical diagnoses with care and even reluctance, for it is perfectly possible that the lesion seen on imaging is in fact asymptomatic and another lesion that is not shown is at the root of the disability. A common mistake is the combination of a symptomatic glenohumeral arthritis that remains undiagnosed with sonography and an asymptomatic rotator cuff tear that is easily detected with the same technique. We therefore fully agree with Kessel, who states: ‘An X- ray is best used to check a hypothesis which has been formed by history and clinical examination. One should eschew the temptation of a shortcut to the X-ray room or scanner.’25

Plain radiography

The main indications for radiography of the shoulder are evaluation of fractures and dislocations, imaging of bony disorders such as tumours and metastases, and identification of calcifications in or around tendons. Plain radiographs may also be helpful in the evaluation of anterior and posterior instability. Although ultrasonography is nowadays the most frequently used method to evaluate rotator cuff lesions, plain X-ray examination can be of use in the detection of accompanying appearances, such as changes in the coracoacromial arch, an unusual form or a spur off the acromion.26 Radiography is also still advocated in long-standing massive cuff tears.27,28

Ultrasound scanning

Ultrasound scanning is mainly advocated for the detection of full or partial rotator cuff lesions. In experienced hands it can reveal not only the integrity of the rotator cuff but also the thickness of its various component tendons. Through careful positioning and through knowledge of the dynamic anatomy of the cuff, the experienced ultrasonographer can image selectively the upper and lower subscapularis, the biceps tendon, the anterior and the posterior supraspinatus, the infraspinatus and the teres minor. Ultrasonography has further advantages: it is non-invasive and safe, bilateral examinations are quickly performed, the shoulder can be examined dynamically and, above all, the procedure is inexpensive.29

One important disadvantage, however, is that the method has a long learning curve. The results are examiner-dependent and a good outcome can only be expected in experienced hands.30 Specificity and sensitivity of as high as 98% and 91% respectively in comparison with surgical findings were claimed by Mack et al.31 Others have found an overall sensitivity of 97% in diagnosing full cuff tears and of 91% in partial thickness tears.32

Arthrography

Single-contrast arthrography can be helpful in diagnosing complete tears of the rotator cuff, incomplete deep surface tears and instability problems.33 It will show loss of axillary-fold space and diminished joint capacity in adhesive capsulitis, but because this disorder is so easy to detect clinically, arthrography should never be required. It is of no assistance in clarifying the differential diagnosis in cases of impingement, in the absence of a rotator cuff tear.

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy is useful for both diagnosis and treatment.34–39 It should be regarded as an adjuvant in those cases where the normal diagnostic aids are insufficient.35 As it offers an excellent view of the glenoid, labrum and capsule, it is an excellent technique in repair of shoulder instability.36

However, confronted with the almost perfect results obtained through examination technique, the physician should never forget that full and partial tears of the rotator cuff exist in a substantial part of a normal asymptomatic population. Both cadaveric studies37,38 and imaging studies39,40 on asymptomatic individuals have demonstrated that cuff defects become increasingly common after the age of 40 and that most occur without substantial clinical manifestations.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has rapidly become a commonly used technique for shoulder evaluation, proving its utility in the evaluation of muscle, tendons, hyaline and fibrous cartilage, joint capsule, fat, bursae and bone marrow.41 Today it is the most accurate non-invasive method available for imaging the rotator cuff.42 The major advantages of this modality include its non-invasive nature, lack of ionizing radiation, excellent contrast and anatomic resolution, multiplanar imaging capability, and ability as a single imaging modality to evaluate simultaneously for a wide variety of pathologic processes.43 One disadvantage is that small foci of soft tissue calcification may be missed on MRI.44 As with all techniques that provide optimal visualization, one should always take into account the high rate of asymptomatic lesions and never rely simply on the outcome of the technique to make a diagnosis and start a treatment.45–48

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is equally as accurate as MRI for evaluation of the glenoid rim and labrum, the humeral head and the glenohumeral capsule. Nevertheless, MRI is to be preferred because it is more accurate in tendinopathies and no X-ray exposure occurs.49 In shoulder instability, CT-arthrography seems to be the best diagnostic method.50

References

1. Herberts, P, Kadefors, R, A study of painful shoulder in welders. Acta Orthop Scand 1976; 47:381–387. ![]()

2. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine. vol I. Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

3. Annaert, JM, Peetrons, P, Famaey, JP, Paraclinical diagnostic procedures in micro- and macrotraumas of the shoulder. Indications for echography and CT scanning. Rev Med Brux. 1990;11(3):47–53. ![]()

4. Clark, J, Sidles, J, Matsen, A, The relationship of the glenohumeral joint capsule to the rotator cuff. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1990; 254:29–34. ![]()

5. Hollingworth, G, Ellis, R, Hattersley, T, Comparison of injection techniques for shoulder pain: results of a double blind, randomised study. BMJ 1983; 287:1339–1341. ![]()

6. Kingma, M, Schouderpijn. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1976;120(8):325–337. ![]()

7. Blécourt, J, De periarthritis humeroscapularis. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1960; 104:369. ![]()

8. Wirth, C, Kohn, D, Melzer, C, Markl, A, Value of diagnostic measures in soft tissue diseases and soft tissue lesions of the shoulder joint. Unfallchirurg. 1990;93(8):339–345. ![]()

9. Yuksek, YN, Akat, AZ, Gozalan, U, et al, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia. Am J Surg. 2008;195(4):533–536. ![]()

10. Scawn, ND, Pennefather, SH, Soorae, A, et al, Ipsilateral shoulder pain after thoracotomy with epidural analgesia: the influence of phrenic nerve infiltration with lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 2001;93(2):260–264. ![]()

11. Jones, DR, Detterbeck, FC, Pancoast tumors of the lung. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1998;4(4):191–197. ![]()

12. Yacoub, M, Hupert, C, Shoulder pain as an early symptom of Pancoast tumor. J Med Soc N J. 1980;77(9):583–586. ![]()

13. Zarkadas, PC, Throckmorton, TW, Steinmann, SP, Neurovascular injuries in shoulder trauma. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39(4):483–490. ![]()

14. Biundo, JJ, Jr., Mipro, RC, Jr., Djuric, V, Peripheral nerve entrapment, occupation-related syndromes, sports injuries, bursitis, and soft-tissue problems of the shoulder. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1995;7(2):151–155. ![]()

15. Postacchini, F, Perugia, D, Gumina, S, Acromioclavicular joint cyst associated with rotator cuff tear. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1993; 294:111–113. ![]()

16. Pellecchia, GL, Paolino, J, Connell, J, Intertester reliability of the Cyriax evaluation in assessing patients with shoulder pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;23(1):34–38. ![]()

17. Hayes, KW, Petersen, CM, Reliability of classifications derived from Cyriax’s resisted testing in subjects with painful shoulders and knees. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(5):235–246. ![]()

18. Hanchard, NC, Howe, TE, Gilbert, MM, Diagnosis of shoulder pain by history and selective tissue tension: agreement between assessors. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35(3):147–153. ![]()

19. Petersen, CM, Hayes, KW, Construct validity of Cyriax’s selective tension examination: association of end-feels with pain at the knee and shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(9):512–521. ![]()

20. Chesworth, BM, MacDermid, JC, Roth, JH, Patterson, SD, Movement diagram and ‘end-feel’ reliability when measuring passive lateral rotation of the shoulder in patients with shoulder pathology. Phys Ther. 1998;78(6):593–601. ![]()

21. Clark, HD, McCann, PD, Acromioclavicular joint injuries. Orthop Clin North Am 2000; 31:177–187. ![]()

22. Reilly, P, Macleod, I, Macfarlane, R, et al, Dead men and radiologists don’t lie: a review of cadaveric and radiological studies of rotator cuff tear prevalence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(2):116–121. ![]()

23. Yamamoto, A, Takagishi, K, Osawa, T, et al, Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):116–120. ![]()

24. Worland, RL, Lee, D, Orozco, CG, et al, Correlation of age, acromial morphology, and rotator cuff tear pathology diagnosed by ultrasound in asymptomatic patients. J South Orthop Assoc. 2003;12(1):23–26. ![]()

25. Kessel, L. Clinical Disorders of the Shoulder, 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1986.

26. Bigliani, LU, Morrison, D, April, EW. The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to rotator cuff tears. Orthop Trans. 1986; 10:228.

27. Pearsall, AW, 4th., Bonsell, S, Heitman, RJ, et al, Radiographic findings associated with symptomatic rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(2):122–127. ![]()

28. Nové-Josserand, L, Edwards, TB, O’Conner, DP, et al, The acromioclavicular and coracohumeral intervals are abnormal in rotator cuff tears with muscular fatty degeneration. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; 433:90–96. ![]()

29. Teefey, SA, Rubin, DA, Middleton, WD, et al, Detection and quantification of rotator cuff tears. Comparison of ultrasonographic, magnetic resonance imaging, and arthroscopic findings in seventy-one consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(4):708–716. ![]()

30. Iannotti, JP, Ciccone, J, Buss, DD, et al, Accuracy of office-based ultrasonography of the shoulder for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1305–1311. ![]()

31. Mack, LA, Matsen, FA, III., Kiloyne, RF, Ultrasound: US evaluation of the rotator cuff. Radiology 1985; 157:205–209. ![]()

32. Hedmann, A, Fett, H, Ultrasonography of the shoulder in subacromial syndromes with disorders and injuries of the rotator cuff. Orthopäde 1995; 24:498–508. ![]()

33. Neviaser, RJ, Radiologic assessment of the shoulder: plain and arthrographic. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18(3):343–349. ![]()

34. Gartsman, GM, Arthroscopic acromioplasty for lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A(2):169–180. ![]()

35. Arens, H, Van der Linden, T. Artroscopie van de Schouder. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1984; 128(49):2334.

36. O’Brien, S, Warren, R, Schwartz, E, Anterior shoulder instability. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18(3):395–408. ![]()

37. Fukada, H, Mikasa, M, Yamanaka, K, et al, Incomplete rotator cuff tears diagnosed by subacromial bursography. Clin Orthop 1987; 223:51–58. ![]()

38. Jerosch, J, Muller, T, Castro, WH, The incidence of rotator cuff rupture. An anatomic study. Acta Orthop Belg. 1991;57(2):124–129. ![]()

39. Sher, JS, Uribe, JW, Posada, A, et al, Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg 1995; 77:933–936. ![]()

40. Milgrom, C, Schaffler, M, Gilbert, S, van Holsbeeck, M, Rotator-cuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand dominance and gender. J Bone Joint Surg 1995; 77B:296–298. ![]()

41. Tirman, PF, Steinbach, LS, Belzer, JP, Bost, FW, A practical approach to imaging of the shoulder with emphasis on MR imaging. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28(4):483–515. ![]()

42. Murray, PJ, Shaffer, BS, Clinical update: MR imaging of the shoulder. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2009;17(1):40–48. ![]()

43. Chaipat, L, Palmer, WE, Shoulder magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(3):371–386. ![]()

44. Polster, JM, Schickendantz, MS, Shoulder MRI: what do we miss? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(3):577–584. ![]()

45. Shahabpour, M, Kichouh, M, Laridon, E, et al, The effectiveness of diagnostic imaging methods for the assessment of soft tissue and articular disorders of the shoulder and elbow. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65(2):194–200. ![]()

46. Moosmayer, S, Tariq, R, Stiris, MG, Smith, HJ, MRI of symptomatic and asymptomatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears. A comparison of findings in 100 subjects. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(3):361–366. ![]()

47. Yamaguchi, K, Ditsios, K, Middleton, WD, et al, The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1699–1704. ![]()

48. Hirano, Y, Sashi, R, Izumi, J, et al, Comparison of the MR findings on indirect MR arthrography in patients with rotator cuff tears with and without symptoms. Radiat Med. 2006;24(1):23–27. ![]()

49. Rafii, M, Firooznia, H, Sherman, O, et al, Rotator cuff lesions: signal patterns at MR imaging. Radiology. 1990;177(3):817–823. ![]()

50. Van Oostayen, J, Bloem, J, Obermann, W, et al, Computertomografie na artrografie bij instabiliteit van het schoudergewricht. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1993;137(5):236–240. ![]()

51. Verdonk, R, Van Meirhaeghe, J, Van Houcke, H, et al, Shoulder bursoscopy. Acta Orthop Belg. 1988;54(2):233–250. ![]()