chapter 21 Clinical Evaluation for Possible Child Abuse

Obtaining the History

Physical Examination

Documentation

Obtaining Pertinent History

Formulating questions for history of present illness

| Child: | “He hurt my noonoo.” |

| Physician: | “Hmmm, I’m not sure I know exactly what you mean when you say noonoo, do you know another word for it?” |

| Child: | “You know, my privates!” |

| Physician: | “Oh, I see. Just to be sure I’m thinking of the right privates, “Can you show me where your noonoo is?” |

| Child: | “There, silly!” |

| Child: | “He put his stick in my bird.” |

| Physician: | “Do you mean his penis?” |

| Child: | “Yes.” |

| Physician: | “Is your bird your vagina?” |

| Child: | “Uh-huh” |

| Physician: | “Did it hurt?” |

| Child: | “Yeah.” |

| Physician: | “Did he put it in your mouth?” |

| Child: | “Yes.” |

| Physician: | “How about your bum?” |

| Child: | “He put his stick in my mouth.” |

| Physician: | “In your mouth?” |

| Child: | “Yeah and sometimes my bird too.” |

| Physician: | “Hmmm. What’s that like?” |

| Child: | “Kinda funny ’cause it gets all big and it stands up.” |

| Physician: | “And how does that feel when that happens?” |

| Child: | “Goodish badish.” |

| Physician: | “Really… anything else?” |

| Child: | “Kinda wet and goopy too.” |

| Physician: | “I see…” |

| Child: | “But that’s okay—we use Kleenex on the night table to clean up.” |

Physical Examination

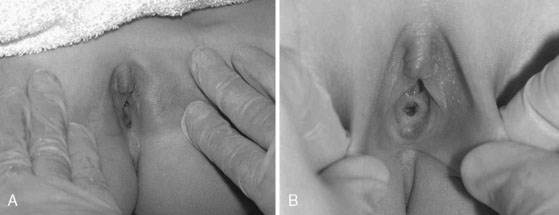

Examination for Sexual Abuse

In girls, the examination for possible sexual abuse is limited to the assessment of the external genital structures only. It is not the same as a gynecologic examination, which is an internal examination. For information on performing a gynecologic examination, see Chapter 18.

Genital Examination

Step 1: Frog-leg position with lateral traction of the labia majora

The supine frog-leg position (Fig. 21–4) is an ideal initial position to visualize the external structures of the vulva and provide an initial view of the hymen. This position should be used for visualization of the female genitalia during well-child visits, when a more in-depth look at the hymen is not required. This position has the advantage of being less invasive and more natural, helping the patient relax. It can be used on an examination table or, for the insecure younger patient, on a parent’s lap. In this position, the labia majora usually separate automatically, exposing the introitus. Gentle lateral traction of the labia majora can help visualize the labia minora, clitoris, posterior fourchette, and hymen.

FIGURE 21–4 Supine frog-leg position.

(From McCann JJ, Kerns DL: The Anatomy of Child and Adolescent Sexual Abuse: A CD-ROM Atlas/Reference, Intercorp Inc., 1999)

Step 2: Frog-leg position with downward traction of the labia majora

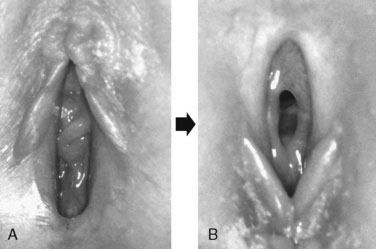

Figure 21–5 illustrates the labial traction and retraction techniques and the difference in hymenal visualization that they offer.

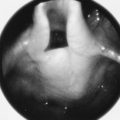

Step 3: Prone knee-chest position

Once the hymen and other genital structures have been identified and examined, if any abnormality is suspected, you must examine them again with the child in the prone knee-chest position (Fig. 21–6). This is especially important when suspicious findings are identified with the child in the supine frog-leg position. The hymen may look abnormal in the supine position because of the effects of gravity on the anterior vaginal wall and to the adherence of mucosal surfaces. By turning the patient into the prone knee-chest position, the effects of gravity are reversed by pulling the posterior hymenal edge and anterior vaginal wall in the opposite direction. If they are real, the same defect(s) seen in the supine position should be visible with the child in the prone knee-chest position. Findings that disappear indicate positional changes in the hymen’s appearance and are not true abnormalities.

FIGURE 21–6 The knee-chest position.

(From McCann JJ, Kerns DL: The Anatomy of Child and Adolescent Sexual Abuse: A CD-ROM Atlas/Reference, Intercorp Inc., 1999)

To visualize the hymen with the child in this position, place your thumbs lateral to the area of the posterior fourchette, with the palms of your hands on the patient’s buttocks. With your thumbs, gently lift the tissues superiorly and laterally, in effect, lifting the posterior vaginal wall against gravity (Fig. 21–7). Using this technique, the posterior hymen should be clearly visible, smoothed out by the effects of gravity. Figure 21–8 demonstrates the striking conformational change in the hymen when the patient is changed from the supine frog-leg position to the prone knee-chest position.

FIGURE 21–7 Examination of the hymen in the knee-chest position.

(From McCann JJ, Kerns DL: The Anatomy of Child and Adolescent Sexual Abuse: A CD-ROM Atlas/Reference, Intercorp Inc., 1999)

Specialized techniques for examining the postpubertal patient

If the swab slips out into the vestibule, be sure to determine whether it has slipped out because of the presence of a hymenal transection or because of the examination technique (Fig. 21–9). Normally, the posterior hymen should not exhibit deep transections that extend to the vaginal wall.

If the less invasive swab technique is not successful, you can insert the tip of a Foley catheter into the introitus, inflate the balloon, and gently pull the catheter out of the vagina. Doing so will stretch out the margins of the hymen and allow for visualization of the posterior rim (Fig. 21–10).

Assessing Children for Physical Abuse and Neglect

Triage of referrals

The Student Consult Web site offers a section on triaging cases of physical abuse.

Formulating questions

| Physician: | “What’s this?” |

| Child: | “A bruise.” |

| Physician: | “How did you get it?” |

| Child: | “It’s from the slipper.” |

| Physician: | “What do you mean?” |

| Child: | “You know, when I pee in my bed.” |

Functional Inquiry

Physical examination for suspected neglect

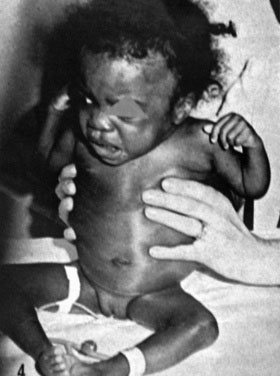

Look for redundant skin folds secondary to weight loss on the buttocks and extremities, hypotonia, poor muscle bulk, severe diaper dermatitis, or plagiocephaly. In the absence of congenital torticollis, plagiocephaly often results from children lying on their backs for prolonged periods of time. Observe the child’s posture; some children with chronic deprivation maintain the typical infantile posture that normally disappears after the first 4 or 5 months (i.e., flexed elbows, hips and knees, with closed fists held close to the face). The classic posture of sensory deprivation involves the sustained external rotation of the shoulder, flexion at the elbows, with the arms pronated and hands near the head or face, often with clenched fists. Sometimes similar flexion at the hips and knees is seen in the frog-leg position, along with supinated feet (Fig. 21–11).

Notes on Photography

“I certify that I took this photograph on October 31, 2009, and that it was not altered.”

If at all possible, use a separate computer folder for the involved patient.

Adams J.A. Guidelines for medical care of children evaluated for suspected sexual abuse: an update for 2008. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:435-441.

Block R.W., Krebs N.F., Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect and the Committee on Nutrition. Failure to thrive as a manifestation of child neglect. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1234-1237.

Kellogg N.D., Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics, 116:2, 2005;506-512. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/reprint/116/2/506.

Kellogg N.D., Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):1233-1241.

Kellogg N.D., Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Oral and dental aspects of child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics, 116:6, 2005;1565-1568. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/reprint/116/6/1565.

Kellogg N.D., Menard S.W., Santos A. Genital anatomy in pregnant adolescents: “Normal” does not mean “nothing happened.”. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1):e67-e69.