chapter 16 Clinical Endocrine Evaluation

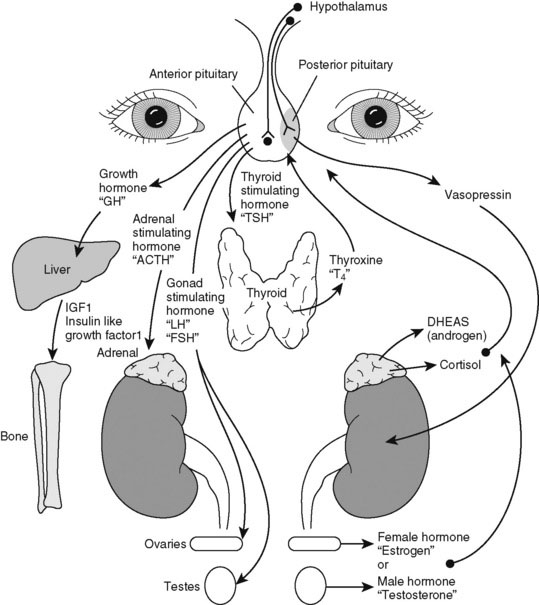

Pediatric endocrinology has special appeal because most childhood endocrine disorders are treatable. A specific diagnosis is usually possible on clinical grounds alone. Do not be intimidated by the myriad of hormone assays and endocrine tests needed to evaluate excesses or deficiencies. We have neatly arranged them all in an interrelated hormone map, which shows the feedback control of hormone action (Fig. 16–1). A good practice is to draw such a picture as you are explaining the details of hormone action to the family. Doing so slows down your explanation and makes you translate the medical lingo while still providing the correct names for hormones.

Approach to the Physical Examination of a Child with Possible Growth Hormone Deficiency

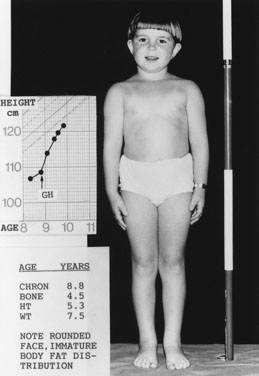

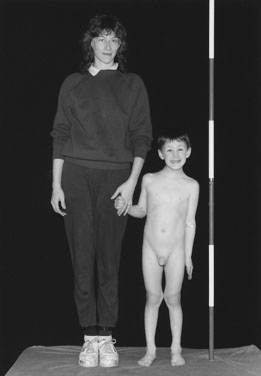

Children with GHD are described as cherubic (Figs. 16-2 through 16-4). They appear younger than their chronologic age, having a rounded face, chubby limbs, and “puddling” (or dimpling) of the anterior abdominal fat. Because of their infantile appearance, further enhanced by a high-pitched reedy voice, adults may baby them or classmates may carry them around like the class pet.

Height and weight percentiles (see Fig. 3–4) are usually discrepant in GHD, with a high weight-to-height ratio. This is a major clue to the need for detailed endocrine investigation. Chronic disease, especially inflammatory bowel disease, may be quite silent and manifest as short stature but, by contrast, with a low weight-to-height ratio.

When available, it is important to include the measurement of both biological parents of the child as a part of the assessment and to calculate the mid-parental height (see Chapter 3) to assess the child’s growth in the context of what would be expected for the family.

Investigate a growth velocity of less than 5 cm per year in children age 5 years to puberty; a growth velocity of less than 4 cm per year is clearly pathologic (see Chapter 3).

You cannot assess short stature or analyze growth velocity without examining the breasts and genitalia to determine the child’s pubertal stage (see Fig. 3–9).

Chief Characteristics of Thyroid Disorders in Children

Structure, function, signs, and symptoms

Evaluating a Child with Hyperthyroidism

Evaluating a Child with Hypothyroidism

Like children with hyperthyroidism, children with hypothyroidism rarely complain of symptoms (Box 16–1) perhaps because the changes develop so insidiously that neither child nor parent notices the difference. When symptoms go unrecognized for years, linear growth is profoundly impaired and may be the presenting feature.

Causes of Childhood Hypothyroidism

Case History 2

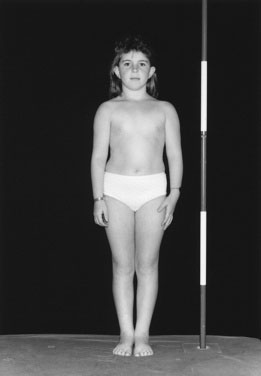

History. Shauna, age 15 years, says, “I was the tallest in my class in fifth grade, but I have not grown since then, and my periods haven’t started” (Fig. 16–5).

Your physical examination reveals all of the physical findings for hypothyroidism that are listed in Table 16–1. You particularly note the characteristic puffiness around Shauna’s upper face and eyes. In this case, because of profound hypothyroidism, there is also a more generalized swelling, including the neck.

| Type of Precocious Puberty | Underlying Cause |

|---|---|

| Central | Idiopathic Hypothalamic hamartoma Germinoma (pinealoma) Other cerebral tumors or malformations Severe hypothyroidism Secondary to cranial irradiation |

| Gonadal | Benign precocious thelarche (? central) Ovarian cysts, benign McCune-Albright syndrome (polyostotic fibrous dysplasia of bone, ovarian cysts, large irregular café-au-lait spots) Leydig cell hyperplasia (familial testotoxicosis) Gonadal tumors (male and female) Isolated premature menses (? central) |

| Adrenal | Benign premature adrenarche Congenital adrenal hyperplasia Adrenal tumors |

| Iatrogenic | Exogenous sources |

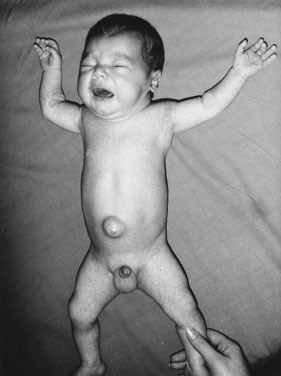

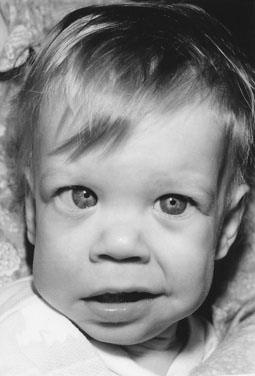

In a few infants, hypothyroidism is caused by a congenital enzyme defect in thyroid hormonogenesis. In such instances, a goiter is present. In many countries, congenital hypothyroidism is now detected in the presymptomatic stage, before any significant intellectual deficit occurs, through blood spot screening between the second and fifth days of life. If congenital hypothyroidism is left untreated, the clinical manifestations may not become fully apparent until around the third month of life.

The infant with untreated congenital hypothyroidism has a low core body temperature, slow pulse rate, prolonged neonatal jaundice (because of poor hepatic conjugation of bilirubin), dry skin and hair, a large posterior fontanel (greater than 0.5 cm), poor head control, poor muscle tone, an enlarged tongue, a characteristically puffy face, and a hoarse cry (Fig. 16–6). The parents may report poor feeding and constipation. If acquired hypothyroidism develops after age 2 or 3 years, no permanent intellectual deficit is thought to occur.

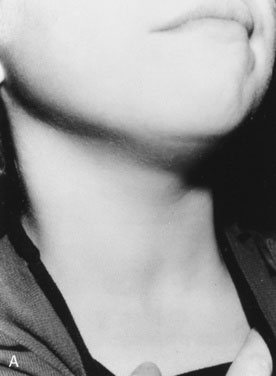

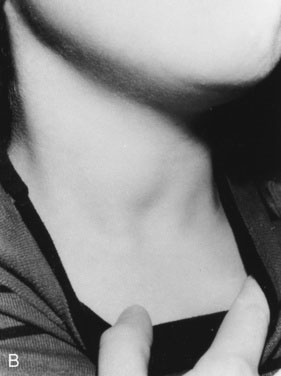

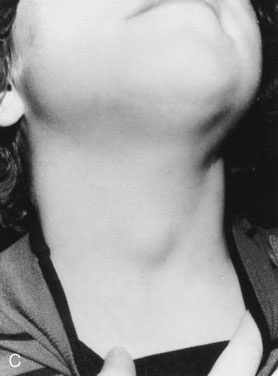

Approach to the Physical Examination of the Child with a Thyroid Disorder

As with other pediatric examinations, always begin with the hands-off approach. Children are often ticklish, and touching the neck may elicit giggles and squirming, making it difficult to see the thyroid. Sit the child on a chair or examining table, with good light and in a relaxed atmosphere. If the child is old enough and cooperative, ask him or her to take a sip of water, first hold the water in the mouth without swallowing, and then swallow. Observe the area just above the sternal notch to see whether the small thyroid gland moves up and down during swallowing (Fig. 16–7). Next, ask the child to hyperextend the neck. This maneuver makes thyroid enlargement more obvious, and sometimes it is the only way to see the gland easily.

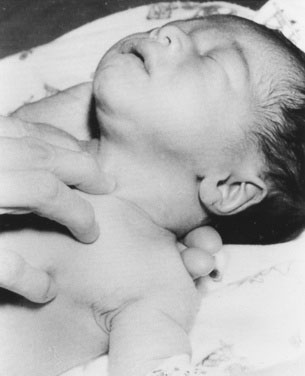

Examining newborns and young infants

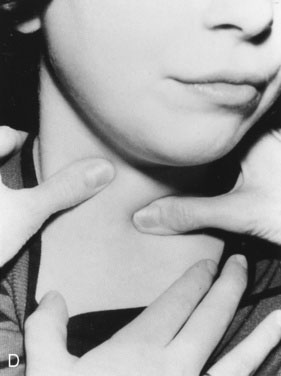

In a newborn or young infant, use a different technique to examine the thyroid. Place your hand under the child’s back, between the scapulae, and raise the baby’s shoulders, allowing the head to fall back gently until it rests on the examining table or a parent’s lap. If the thyroid is enlarged, this maneuver will expose it, allowing you to palpate with the second and third fingers of your other hand (Fig. 16–8).

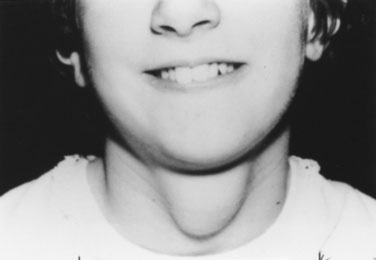

Examining young children and adolescents

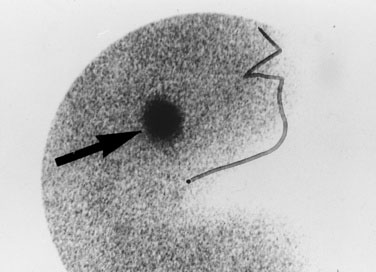

Most midline neck masses are thyroid glands or thyroid remnants. A central rounded midline mass between the thyroid and the chin is almost certain to be a thyroglossal duct cyst (Fig. 16–9), derived from a remnant of the thyroglossal duct, which runs from the foramen cecum of the tongue downward to the cricoid cartilage during fetal development. When the child sticks out the tongue, the mass moves upward. The child may present initially with an infected thyroglossal duct cyst. Sometimes, the gland fails entirely to migrate downward from the foramen cecum and manifests clinically as an oval or rounded midline mass at the base of the tongue (Fig. 16–10). This lingual thyroid usually represents all of the thyroid that the child has. Most lingual thyroids are treated with daily therapy using l-thyroxine, which suppresses pituitary thyrotropin (TSH) secretion, causing the lump to shrink markedly.

Causes of Hypercalcemia

Case History 3

Some infants with idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia have a characteristic facial appearance (Williams syndrome), consisting of full cheeks, a wide mouth, and a stellate iris, typically associated with supravalvular aortic stenosis or other cardiovascular lesions (Fig. 16–11). Infantile hypercalcemia can be associated with subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn, so it is important to look for areas of firm reddened nodules on the child’s trunk, limbs, or cheeks. Also ask about a history of this type of lesion because sometimes the lesion has resolved by the time the hypercalcemia is discovered. An asymptomatic condition known as familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia is generally discovered incidentally or during family screening studies. The etiology is an autosomal dominant defect in the calcium-sensing receptor. The volume of urine does not increase (therefore, neither does the thirst) because the urine calcium level is low, partly explaining the paucity of symptoms. Because the condition is caused by a calcium-sensing defect, the serum parathyroid hormone level is usually in the normal range, not suppressed as it would be in a normal individual.

Approach to the Physical Examination of a Hypocalcemic Child

Case History 4

Hypocalcemia may occur secondary to hypoparathyroidism or pseudohypoparathyroidism (an abnormality of the parathyroid hormone receptor) or in association with vitamin D deficiency. The most common causes of hypoparathyroidism (aside from surgical removal of the gland) are autoimmune destruction and the absence or maldevelopment of the parathyroid glands. This condition may also be associated with aortic arch abnormalities and the absence or diminished function of the thymus and a microdeletion of chromosome 22q11.2. Children with pseudohypoparathyroidism typically show moderate obesity, with ovoid facies, mild to moderate intellectual deficit, and short fourth or fifth metacarpals (see Fig. 16–12). When the child makes a fist, the fourth and fifth knuckles are short, a sign also seen in girls with Turner (karyotype XO) syndrome.

Chief Characteristics of Adrenal Disorders in Children

Evaluating cushing syndrome

Observe the child from all sides to assess body fat distribution. In adults with Cushing syndrome, the adiposity is clearly central; they have slim limbs, thin hands, and a rounded face. Young children with Cushing syndrome have more generally distributed body fat that is still maximal in the face, trunk, and cervical region, but the adiposity is chunkier and more solid in the very young, almost seeming to bury their small features (Fig. 16–13). We never tell patients that they have a buffalo hump, preferring the term increased posterior cervical fat pad because it sounds less derogatory.

Striae (stretch marks) are unusual before the teen years. In Cushing syndrome, these marks are violaceous rather than the pink to silver color seen in obesity or during rapid growth in normal adolescents. Check the scalp hairline. Fine lanugo hair growing down from the scalp to the forehead, from the occipital region to the nape of the neck, and sweeping down the lateral cheek suggests excess cortisol exposure. A small amount of fine hair may be distributed over the entire body, including the pubic region. Cortisol excess increases red cell production, giving the child a ruddy, plethoric complexion. It also inhibits protein synthesis, resulting in muscle atrophy, decreased strength, thin fragile skin and vasculature, and susceptibility to bruising. Osteoporosis, a significant sequela, may be manifested by back pain due to vertebral compression fractures. This condition is particularly evident in children who have received high-dose glucocorticoid therapy for prolonged periods to control a primary disease (see Fig. 16–14).

Once you suspect Cushing syndrome, how can you localize its cause? Increased pigmentation suggests a pituitary etiology, such as an adenoma with increased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion, although the pigmentary change is far less dramatic than in Addison disease. Always note the parents’ complexion so as not to be misled by familial pigmentary characteristics. Pituitary tumors can press on the optic chiasm, causing visual field defects—classically, bitemporal hemianopsia with optic atrophy (see Chapter 8). On clinical grounds alone, it can be extremely difficult to differentiate Cushing syndrome with a central etiology from that caused by an adrenal tumor. Sophisticated laboratory and imaging investigations are usually required to make the distinction.

Androgen excess

Benign Premature Adrenarche

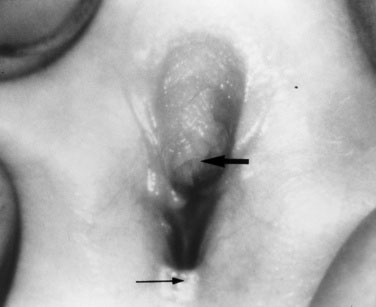

The absence of penile enlargement in boys or of clitoral enlargement in girls distinguishes benign premature adrenarche from pathologic virilization. If a female fetus were exposed to excessive androgen in utero, the clitoris enlarges, and the labia may fuse posteriorly (Figs. 16-15 through 16-18).

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

The clinical presentation of classic salt-losing virilizing CAH is dramatic, and early recognition and treatment are lifesaving. The infant with this condition may present in shock and is profoundly dehydrated, limp, and pale, with little response to painful stimuli (Fig. 16–19). The clinical tip-off may be that the extent of collapse and shock far exceeds the reported level of gastrointestinal loss from diarrhea and vomiting.

A defect in the 11-hydroxylase enzyme causes cortisol deficiency and virilization, as in 21-hydroxylase deficiency, but the affected infant is also hypertensive (because of excess accumulation of 21-deoxycortisol acetate), a feature that stresses the necessity for accurate blood pressure recording, even in newborns. The less common deficiency of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase results in ambiguous genitalia in both male and female infants. (See Chapter 5 for a detailed discussion of the clinical approach to the child with ambiguous genitalia.)

Approach to the Physical Examination of a Child with Ambiguous Genitalia

The female child with hyperandrogenism due to CAH has an enlarged clitoris and normal internal female sexual organs (Fig. 16–20). In a newborn, the enlarged clitoris may resemble a male phallus so closely as to be indistinguishable. The child whose genitalia are shown in Figure 16–18 actually underwent a circumcision 10 days before the signs of acute adrenal insufficiency appeared.

FIGURE 16–20 Genitogram of the patient shown in Figure 16–18. The radiograph demonstrates the bladder, uterus (arrow), and vagina.

Look at the perineum carefully to see whether there is a urethral orifice separate from and anterior to the hymenal ring. When the lower end of the vagina has not formed, as occurs in some females with CAH, there is a fistula from vagina to urethra, with a common external opening. A milder anatomic abnormality may be clitoral hypertrophy with partial fusion of the posterior labia; in this abnormality, the joining skin is thickened, not grayish and transparent as in benign labial agglutination (see Fig. 18–7), a common phenomenon in female infants.

At the other extreme is the child with a normal XY karyotype who has ambiguous genitalia because of an androgen receptor abnormality (Fig. 16–21). The term used to describe a urethral opening on the perineal surface in boys is perineal hypospadias.

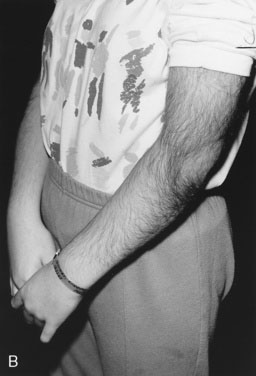

Hirsutism

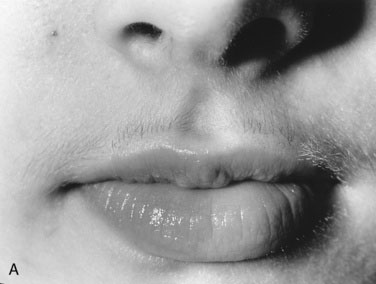

Excessive facial or body hair is most distressing to adolescent girls and their parents, but you should explain that it is usually simply a variation of “normal.” Hair growth increases and becomes courser (terminal hair) in the androgen-dependent areas: on the upper lip, chin, and cheeks, between the breasts, across the chest, shoulders, and back (including the sacral area), up the linea alba, across the abdomen, down the inner thigh, and on the limbs and digits. Remember that there is a normal variation in the amount of terminal body hair in women. Asian, Northern European, and sub-Saharan African women have the least terminal hair, while women of Mediterranean and Indian subcontinent descent have more. Individuals whose hair is more darkly pigmented will appear more hirsute. Generally beginning at puberty, hirsutism becomes more troublesome with age. Pay attention to hirsutism that develops at puberty so you can offer investigation and treatment before the hair growth becomes well established and impossible to reverse (Fig. 16–22).

The etiology of hirsutism may be nonclassic CAH, in which the enzyme block is only partial. Affected patients have no evidence of adrenal insufficiency but, because of 21-hydroxylase enzyme deficiency, may experience precocious adrenarche and, at puberty, hirsutism. Hirsutism may be idiopathic, with hair follicles that are excessively sensitive to normal levels of androgen. Another cause is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), in which there is excess androgen production or effect from ovarian androgens. PCOS in the adolescent is typified by anovulatory cycles (oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea), and clinical or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, usually associated with obesity. In addition to hirsutism, girls with hyperandrogenism may have acne or male pattern hair loss. Hirsutism typically begins around the time of puberty. In some cases, precocious adrenarche is the forerunner. There is a strong familial incidence, although the genetics have not been clearly defined; therefore, always ask about hirsutism, irregular menses and difficulty with conception in female relatives. Associated high insulin levels, a risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus, are also characteristic. In every case, look for acanthosis nigricans. This thickened, raised, velvety brown appearance to the skin folds in the neck, axillae, or groin, between the breasts, or over pressure points like the elbow or knuckles is the hallmark of hyperinsulinism (Fig. 16–23). Usually, affected children have been accused of not washing their necks, but no amount of scrubbing helps.

Approach to the Physical Examination of a Child with Adrenal Insufficiency

The child in an acute adrenal crisis is dehydrated and extremely lethargic. Recumbent blood pressure may be normal but falls precipitously upon standing or sitting. In primary adrenal failure, there is increased pigmentation over pressure or friction points (such as elbows [Fig. 16–24] or knees) and on buccal surfaces, gingival margins, nail bases, palmar creases, and scars that develop after the disorder begins. Even pigmented nevi darken. This darkening is due to increased ACTH production, which stimulates melanocytes. (The first 13 amino acids in the ACTH sequence are identical to those in melanocyte-stimulating hormone.)

Pubertal Development: Precocious, Delayed, and Normal Variants

General definitions

Central precocious puberty is idiopathic in the majority of cases. Identifiable causes include hypothalamic tumors and hamartomas (normal tissue in a tumorous collection). Noncentral precocious puberty does not originate in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis; it results from increased sex hormone secretion from the adrenal glands or gonads. CAH is one example. See Table 16–1 for a list of the causes of precocious puberty.

Obtaining the history

For a child whose pubertal development is abnormal, you must evaluate the psychosocial impact. Is excessive masturbation a problem? How do the parents deal with the problem? Do they hug and cuddle this 4-year-old who looks and sounds like a small man but acts like a small child (Fig. 16–25)?

Approach to physical examination of children with precocious puberty

Take height measurements 6 months to 1 year apart so that you can calculate the child’s growth velocity (see Chapter 3), which is accelerated. Chronic or acute increases in intracranial pressure, secondary to a central tumor, cause optic atrophy or papilledema. Carefully document the visual acuity, visual fields, and extraocular movements. Occasionally, children with hypothyroidism experience precocious puberty, but they are short, with decreased growth velocity for age. Look for café au lait spots, brown macular pigmented areas on the skin with either a smooth border, consistent with neurofibromatosis, or an irregular outline, consistent with McCune-Albright syndrome (Fig. 16–26). Both conditions can be associated with precocious puberty, the former with central precocious puberty. In McCune-Albright syndrome, the precocious puberty is not central, and the child may have multiple ovarian cysts and completely suppressed pituitary gonadotropins, but menses often begin before age 4 years. These children also have the bone lesions of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, evident on radiographs.

To examine a child’s breasts, observe the contour, palpate for breast tissue to distinguish true breast tissue from excess adiposity and record the breast diameter. Is the nipple pale, thin, and translucent (Fig. 16–27), as in isolated breast enlargement (precocious thelarche)? This common reversible condition seen in toddlers does not usually progress to true precocious puberty. Alternatively, is the areola dark, indicating high circulating estrogen levels, with a prominent nipple mound, as seen in the 3-year-old girl with McCune-Albright syndrome shown in Figure 16–26? This child demonstrated precocious puberty with menses at age 18 months. Note also the irregular contours of the café au lait spot over the right breast—a clue to the etiology of the precocity.

When there is a significant postnatal increase in circulating estrogen, regardless of its source, the labia minora become enlarged and thickened (Fig. 16–28), vaginal secretions (leukorrhea and/or menses) begin, and breast buds appear.

Testicular examination

Estimate testicular volume using an orchidometer (Fig. 16–29). A volume of 4 mL is equivalent to 2.5 cm long and corresponds with Tanner stage 2 or the beginning of puberty (see Fig. 3–9). Enlargement suggests a testicular origin for androgen production. If you have a tape measure only, you can derive the testicular volume from measurements of width and length, using the following formula:

FIGURE 16–29 An orchidometer. Note the numerical volumes in milliliters printed on the beads. Prepubertal testicles are 1 to 3 mL.

At Tanner stage 3, testicular volume is between 10 and 12 mL.

Physical findings in delayed puberty

Although by far the most common cause of delayed puberty is physiologic (constitutional) delay, usually associated with delayed growth, the history and physical examination helps exclude pathologic causes. A classification dividing the causes into central (hypothalamic and/or pituitary) and gonadal is given in Table 16–2. Although the list is not exhaustive, it provides an orderly approach to the evaluation of teenagers who are worried about their sexual development. Their stature may be normal or shorter than normal, and their growth velocity is below normal for their chronologic age. The exceptions are boys with Klinefelter syndrome (karyotype XXY gonadal dysgenesis), who are tall with disproportionately long arms and legs, normal adrenarche, and small testes, which may be cryptorchid. These children are often overweight and may show delayed social and intellectual development.

| Type of Delayed Puberty | Causes |

|---|---|

| Central | Physiologic (Constitutional) delay Malnutrition (including anorexia nervosa) Intensive physical training Chronic illness Hypothalamic and/or pituitary Developmental/genetic Destructive Surgical Radiotherapy Tumor Drugs (e.g., cyproterone acetate, luteinizing hormone agonists) Other endocrine (including hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinemia) |

| Gonadal | Developmental Vanishing testes caused by antenatal testicular torsion Anatomic abnormalities of female genital tract Chromosomal XXY Klinefelter syndrome XO Turner syndrome Immunologic Autoimmune endocrinopathy (oophoritis) Destructive Surgical removal of gonads Radiotherapy/chemotherapy |

When pubertal delay is combined with short stature in girls, always consider Turner syndrome (karyotype XO), the physical characteristics of which include a short, wide-based neck, low anterior and posterior hairline, shield-shaped chest, absence of breast development, increased elbow-carrying angle, a short fourth metacarpal (see Fig. 16–12), and spoon-shaped nails with lateral margins buried deeply in the pericuticular skin. In some girls, the signs of Turner syndrome are very subtle, especially if the karyotype demonstrates mosaicism, and the presence of breast development does not preclude the diagnosis. Children with Turner syndrome undergo normal adrenarche, so pubic hair and axillary hair are expected at the appropriate age.

The inability to smell (anosmia) or an impaired sense of smell (hyposmia) may accompany hypothalamic hypogonadism, an association that can be explained because the neurons producing LHRH share their origin with the olfactory nerve. Test the sense of smell (see Chapter 13) in any child with small (and often undescended) testicles and a small penis (less than 2.5 or 3 cm in length and circumference). Remember that it is the intrauterine fetal testosterone level that is responsible for the development of the normal penis size at birth.

Clinical Characteristics of Diabetes Mellitus in Children

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Strong predictors of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) in overweight children are first- or second-degree relatives with diabetes and the presence of acanthosis nigricans (see Fig. 16–23). Not all children who are obese are destined to develop diabetes. The increase in rate of type 2 DM in young people is related to rising rates of obesity in the general population. Obesity in a child older than 6 years, especially when accompanied by parental obesity, correlates with adult obesity, a risk factor for type 2 DM, and also an independent risk factor for adult cardiovascular disease. Careful documentation of the family history should alert you to a genetic predisposition to obesity and provide a stimulus for preventive counseling. Because of concerns about self-esteem, calling attention to personal characteristics of an individual is frowned upon. We often ask parents whether they have any concerns about the child’s growth or weight. Gently questioning the child about lifestyle habits may elicit associated poor eating and exercise habits and excessive sedentary activities. Ask about what activities the child participates in each week, including walking. However, to get a full picture of the situation, it is essential to ask about screen time (TV, computer and video games), which can often be many hours per day. Ask whether the child has a TV, computer, or other electronic gadgets in his or her bedroom. Individual counseling, focused on setting small goals to move toward healthier behaviors, is important. However, population-based remedies are also needed to promote change on a large scale.

The presentation of type 2 DM is generally insidious, with few symptoms at first, much as in adults. With time, polyuria and polydipsia develop once the blood glucose level is sufficiently high. Many children have ketonuria, and diabetic ketoacidosis does occur. With improved public and health professional awareness, children with type 1 DM progress less frequently to ketoacidosis than in the past. However, most are ketotic (have acetone breath and ketones in the urine) and thin. Children with type 2 DM are overweight, but as our population becomes progressively more obese, we are seeing more overweight children, even among patients with onset of type 1 DM, making this unreliable as a differentiating feature. In certain racial groups such as black Americans or among indigenous peoples, it is more likely that the diagnosis will be type 2 DM rather than type 1 DM, but not invariably so. Similarly, in white teens, type 1 DM is most common, but type 2 DM is increasing in this population as well. Type 2 diabetes is rare, but not unknown, before the onset of puberty. The presence of acanthosis nigricans strongly points to type 2 DM as the cause of the diabetes (see Fig. 16–23).

Acute presentation of type 1 diabetes mellitus or acute decompensation in a child previously diagnosed

Table 16–3 contains a useful checklist for significant issues in the history and physical examination of the child with known diabetes who returns for assessment of diabetes control (Figs. 16–30 and 16–31). It is important to remember that diabetes routines are very demanding for the child or teen and their family and often are not fully observed. Clinicians must remember that lecturing a teen about the potential long-term consequences of diabetes is rarely motivating. Using principles of chronic disease management, acknowledge what is done well and help the child or teen and parents to set concrete goals to work together toward getting better results.

TABLE 16–3 Checklist of Significant Issues in History and Physical Examination for Assessment of Diabetes Control

| History | Meal plan and compliance; mealtime problems Insulin Route–pump/injections Dose/pump rates, frequency Timing Sites Adjustment for blood glucose Self-monitoring of blood glucose Frequency Results in book/device memory Device/calibrated? Hypoglycemia Day/night Warning/no warning Mild/moderate Severe (definition: cannot help self)/seizure Usual treatment Exercise Ask what sports Intercurrent illnesses History of gastric discomfort or frequent loose stools may suggest celiac disease (gluten-sensitive enteropathy), as common an associated disease as Hashimoto thyroiditis; poor control of diabetes despite following guidelines may be a useful clue Dental care (silent dental infection may be a cause of poor control) Emotional or psychosocial problems Family functioning/coping School progress School/daycare knowledge of diabetes/hypoglycemia Smoking/drinking Safe sex Driving Test blood sugar before driving Carry sugar to treat lows Wearing a medical alert bracelet or medallion |

| Physical Findings | Growth and pubertal development BMI (interpreted by using age appropriate BMI standards) Blood pressure Funduscopy for microangiopathy (microaneurysms, exudates) Dental examination Goiter or evidence of hypothyroidism (up to 10% of diabetic children experience Hashimoto thyroiditis) Acanthosis nigricans (see Fig. 16–23) (a sign of hyperinsulinism, present in children with, or at risk for, type 2 diabetes mellitus Hepatomegaly (fatty infiltration associated with poor control) Monilial vaginitis in girls/balanitis in boys Insulin injection sites (hypertrophy [Fig. 16–30], lipoatrophy) Neuropathy (ankle jerks, vibration sense) Mobility of finger joints (reduced by increased glycosylation of tissue proteins when blood glucose is chronically high) Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (Fig. 16–31) (a rare but characteristic dermopathy of diabetes; a yellowish or salmon colored, circular, raised lesion with a central area of atrophic fragile skin; generally located over the shins) |

Hall J.G., Froster-Iskenius U.G., Allanson J.E. Handbook of normal physical measurements. Oxford University Press: Toronto, 1989.

Kronenberg H.M., Melmed S., Polonsky K., et al. Williams textbook of endocrinology, 11th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2008.

LeRoith D., Wolfsdorf J.I. Pediatric endocrinology update. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2005;34:3.

Sperling M.A. Pediatric endocrinology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2008.