Clinical Assessment of the Cardiopulmonary System

I Clinical Assessment of the Cardiopulmonary System Requires a Number of Specific Steps.

A Review of the patient’s chart:

A Before entering a patient’s room his or her chart should be reviewed completely.

B This review should identify the reason for the patient’s admission and the type of therapy he or she is to receive.

C An initial review of the chart helps to outline areas where the clinician would ask the patient questions and to help focus the physical examination.

D This initial review also frequently provides insights into the patient’s history, his or her family history, and social and environmental issues that may affect his or her disease.

III The Patient Interview: Medical History

A The interview provides unique information because it is the patients’ prospective on their illness.

B The interview is designed to accomplish three related goals:

1. Establish a rapport between patient and clinician.

2. Obtain essential diagnostic information.

3. Monitor changes in the patient’s symptoms and response to therapy.

C Effective patient interviewing requires that the clinician pay attention to a number of professional issues as listed in Box 18-1.

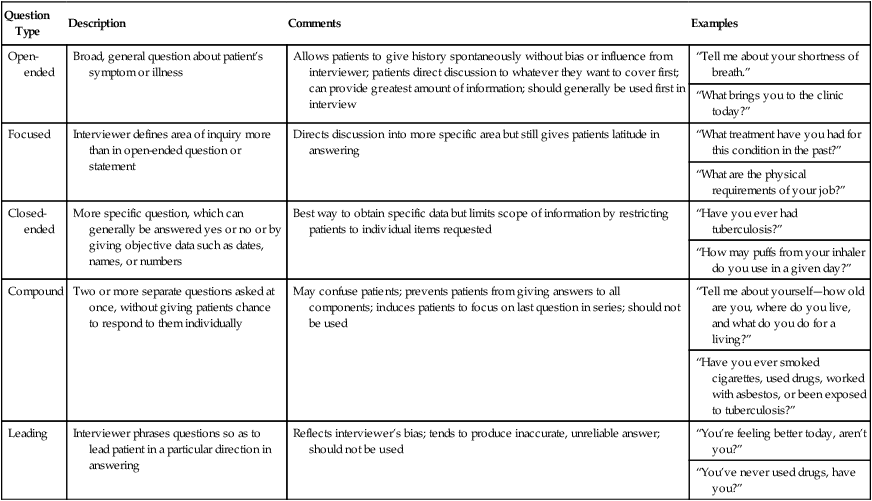

D Questions during the interview can be structured in a number of different ways depending on the type of response the clinician desires. Table 18-1 lists a number of different types of questions.

TABLE 18-1

Types of Questions in Taking a Medical History

| Question Type | Description | Comments | Examples |

| Open-ended | Broad, general question about patient’s symptom or illness | Allows patients to give history spontaneously without bias or influence from interviewer; patients direct discussion to whatever they want to cover first; can provide greatest amount of information; should generally be used first in interview | “Tell me about your shortness of breath.” |

| “What brings you to the clinic today?” | |||

| Focused | Interviewer defines area of inquiry more than in open-ended question or statement | Directs discussion into more specific area but still gives patients latitude in answering | “What treatment have you had for this condition in the past?” |

| “What are the physical requirements of your job?” | |||

| Closed-ended | More specific question, which can generally be answered yes or no or by giving objective data such as dates, names, or numbers | Best way to obtain specific data but limits scope of information by restricting patients to individual items requested | “Have you ever had tuberculosis?” |

| “How may puffs from your inhaler do you use in a given day?” | |||

| Compound | Two or more separate questions asked at once, without giving patients chance to respond to them individually | May confuse patients; prevents patients from giving answers to all components; induces patients to focus on last question in series; should not be used | “Tell me about yourself—how old are you, where do you live, and what do you do for a living?” |

| “Have you ever smoked cigarettes, used drugs, worked with asbestos, or been exposed to tuberculosis?” | |||

| Leading | Interviewer phrases questions so as to lead patient in a particular direction in answering | Reflects interviewer’s bias; tends to produce inaccurate, unreliable answer; should not be used | “You’re feeling better today, aren’t you?” |

| “You’ve never used drugs, have you?” |

From Pierson DJ, Kacmarek RM: Foundations of Respiratory Care. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1992. Churchill Livingstone

E Occupational or environmental exposures are a key aspect of a patient interview. Table 18-2 lists a number of common exposures associated with pulmonary disease.

TABLE 18-2

Common Occupational or Environmental Exposures Associated with Pulmonary Disease

| Occupation or Activity | Exposure | Disease |

| Asbestos mining/milling/manufacture; pipe fitting; shipbuilding/ship fitting; insulation, construction, demolition, living with someone employed in any of the above | Asbestos | Lung cancer, asbestosis, malignant mesothelioma, nonmalignant inflammatory pleural effusion |

| Hard-rock mining, quarrying, stone cutting, abrasive industries, foundry work, sandblasting | Crystalline quartz (silica) | Silicosis |

| Coal mining | Coal dust | Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis |

| Farming, grain handling | Grain dust | Chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Farming, animal attendants | Moldy hay (spores of thermophilic actinomycetes [fungus]) | Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (farmer’s lung) |

| Cotton/flax/hemp workers, textile industry | Cotton dust | Byssinosis |

| Pigeon breeding, bird handling | Proteins derived from parakeets, budgerigars, pigeons, chickens, turkeys (avian droppings or feathers) | Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (e.g., pigeon-breeders’ lung), bird-fanciers’ lung |

| Woodworking, lumber industry | Wood dust, Alternaria (fungus), Western red cedar, oak, others | Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, woodworker’s lung, occupational asthma |

From Pierson DJ, Kacmarek RM: Foundations of Respiratory Care. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1992. Churchill Livingstone

F Symptoms expressed as a concern by patients should be explored in detail. Box 18-2 lists specific questions that should be asked regarding a specific symptom.

G All interviews of patients receiving respiratory care should focus on the following symptoms and signs.

a. The most common symptom of cardiopulmonary disease.

b. Is it dry or loose, productive or nonproductive?

c. A dry nonproductive cough is typical of congestive heart failure (CHF) or pulmonary fibrosis.

d. A loose, productive cough is often associated with bronchitis and asthma.

e. The most common cause of acute cough is viral infection.

f. Chronic coughing is associated with asthma, postnasal drip, chronic bronchitis, and gastroesophageal reflux.

a. Sputum containing pus is purulent.

b. Purulent sputum is thick, colored, and sticky.

c. Clear and thick sputum is mucoid.

d. Recent changes in the quantity, color, or viscosity of sputum are often signs of infection.

a. Defined as coughing up blood or blood-streaked sputum.

b. Hematemesis is vomiting of blood, blood from the gastrointestinal tract.

c. Massive hemoptysis is >300 ml.

d. Nonmassive hemoptysis is seen in tuberculosis, lung cancer, and pulmonary embolism.

e. Blood-streaked sputum is often associated with infection.

f. Massive hemoptysis is seen in lung abscess, bronchiectasis, and trauma.

a. Swelling of lower extremities

b. Normally associated with heart failure, usually right-sided failure.

c. May be severe enough to result in “pitting” when compressed.

a. With the head of the bed elevated 45 degrees, venous distention >3 to 4 cm above the sternal angle is abnormal.

a. Patient-perceived shortness of breath.

b. Occurs when the patient’s sense of the work of breathing exceeds that associated with the effort performed.

c. Orthopnea is dyspnea in the supine or lying position and is associated with heart failure.

d. Platypnea is dyspnea in the upright position seen in patients with right to left intracardiac shunts associated with congenital cardiac disease and venous to arterial shunts in the lung related to severe lung disease or chronic liver disease. Orthodeoxia is oxygen desaturation in the upright position.

a. Chest pain is usually classified as pleuritic or nonpleuritic.

b. Pleuritic chest pain is usually located laterally and posteriorly, worsens with a deep breath, and is described as sharp and stabbing.

c. Pleuritic pain is associated with inflammation of the pleura as a result of pneumonia or pulmonary embolism.

d. Nonpleuritic chest pain is located in the center of the chest and may radiate to the shoulder or back. It is not affected by breathing and is described as a dull ache or pressure.

e. The most common cause of nonpleuritic chest pain is angina, which is associated with coronary artery disease.

f. Nonpleuritic chest pain is also associated with gastroesophageal reflex, esophageal spasm, chest wall pain (costochondritis), and gallbladder disease.

a. A bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membrane caused by the presence of at least 5 g of deoxygenated hemoglobin.

b. May be either peripheral or central.

c. Typically seen in association with hypoxemia in the absence of anemia.

a. Diffuse bulbous enlargement of terminal phalanges of the fingers and toes.

b. Occurs as a result of a buildup of fibroelastic soft tissue in the nail bed.

c. Clubbing is usually asymptomatic and of an unknown mechanism.

a. A high-pitched musical sound produced when a patient breathes.

a. Is the patient oriented to person, place, and time?

b. Box 18-3 lists the terms with their definition of various levels of consciousness.

c. If the patient is falling asleep during the interview, his or her CO2 level may be elevated.

A Temperature: An indicator of metabolic rate.

a. Oral: 97.0 to 99.5°F or 36.5 to 37.5°C.

b. Axillary: 96.7 to 98.5°F or 35.9 to 36.9°C.

c. Rectal: 98.7 to 100.5°F or 37.1 to 38.1°C.

d. Ear: Essentially the same as rectal if measured correctly.

2. Hyperthermia (fever): In the hospitalized patient it is normally indicative of infection, which is usually bacterial but may be viral.

3. Hypothermia is rare in hospitalized patients but may be a result of:

B Pulse: A general reflection of pump capabilities of the heart.

1. Heart rate in adults is normally 60 to 100 beats/min.

a. Heart rates >100 beats/min (tachycardia) may be a reflection of the following:

2. Rhythm: A regular rhythm should be noted. Irregular rhythm may indicate:

3. Strength: The force of the beat should be easily noted.

a. A weak, thready pulse is normally associated with hypotension.

b. A strong bounding pulse may be associated with hypertension.

c. Pulsus paradoxus or paradoxical pulse: A decrease in pulse strength during spontaneous inhalation; frequently a result of changes in auto-positive end-expiratory pressure levels during inspiration and expiration.

d. Pulsus alternans: An alternating succession of strong and weak pulses, suggestive of left-sided heart failure.

C Blood pressure: The force exerted by the arterial pressure against the wall of the artery.

1. Systolic pressure is normally 95 to 139 mm Hg (between 130 and 139 mm Hg currently referred to as prehypertension) in the adult.

2. Diastolic pressure is normally 60 to 89 mm Hg in the adult.

3. Pulse pressure is the difference between the systolic and diastolic pressure, normally 35 to 40 mm Hg. If it is <25 to 30 mm Hg, the peripheral pulse is difficult to palpate. This pressure provides the gradient for peripheral perfusion.

4. Hypertension is a pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg and may be reflective of:

5. Prehypertension, a systolic pressure of 130 to 140 mm Hg, is now considered a precursor to hypertension and requires a change in lifestyle and in some cases treatment.

6. Hypotension is a pressure <95/60 mm Hg and may be reflective of:

V Physical Assessment of the Chest

A Chest assessment includes the following (sequentially performed as listed):

B Inspection is the observation of the patient’s chest configuration and pattern of breathing. During inspection, the following should be evaluated:

a. Is the patient sitting comfortably, or does he or she require support to ventilate?

b. The position assumed provides information about the patient’s use of accessory muscles of ventilation or the presence of pain.

a. Anteroposterior to lateral diameter ratio is normally 1:2. If the patient is barrel-chested, the ratio approaches 1:1, a common finding in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

b. Bony deformities of the thorax

(1) Kyphosis: Posterior curvature of the thoracic vertebral column.

(2) Scoliosis: Lateral curvature of the spinal column.

(3) Kyphoscoliosis: Combination of kyphosis and scoliosis.

(4) Pectus carinatum: Protrusion of the sternum anteriorly.

(5) Pectus excavatum: Depression of the sternum.

(6) Any thoracic deformity may result in restriction of ventilation.

a. Sequence of normal lung expansion

(4) Abnormal sequencing may be a result of underlying lung disease or an increase in cardiopulmonary stress.

b. Uniform bilateral chest expansion

c. Use of accessory muscles of ventilation

(1) Normal inspiration requires only contraction of the diaphragm and external intercostals.

(3) Use of accessory muscles is an indication of increased work of breathing (see Section VI).

d. Acute cardiopulmonary stress normally results in an increased ventilatory rate.

e. Patients with chronic obstructive lung disease may have a decreased ventilatory rate, whereas patients with chronic restrictive lung disease may have an increased ventilatory rate.

f. Pursed lipped breathing is indicative of chronic airway obstruction.

g. Inspiratory/expiratory ratios should be about 1:2.

h. The presence of audible wheezes, crackles, or rhonchi is indicative of secretions or bronchospasm.

C Palpation is the touching of the chest to evaluate movement and underlying lung function.

1. Symmetric movement of the thoracic cage.

2. Tone of ventilatory muscles.

3. Presence of consolidation, pneumothorax, atelectasis, or pleural effusion. These may cause a shift in the mediastinum. Palpation of the trachea at the suprasternal notch identifies shifting.

a. Pneumothorax shifts the trachea and lungs away from the area of the pneumothorax.

b. Consolidation and atelectasis shifts the trachea and lungs toward the affected area.

c. Unilateral pleural effusion shifts the trachea and lungs away from the effusion. A bilateral effusion may not affect position.

4. Fremitus: The vibration produced over the thoracic cage by the conduction of sound waves.

a. Evaluation of fremitus is performed bilaterally to compare the tactile vibrations between sides of the chest.

b. Normally fremitus is equal throughout all lung fields; however, it may be increased over the apex of the right lung.

c. Fremitus is increased if lung density is increased (e.g., pneumonia or consolidation).

d. Fremitus is decreased if atelectasis from obstruction is present or if fluid or air accumulates in the pleural space.

e. A generalized or diffuse decrease in fremitus is noted in those with COPD and muscular or obese chest walls.

5. Subcutaneous emphysema: If it is present, an air leak has allowed gas to enter the tissue.

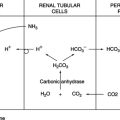

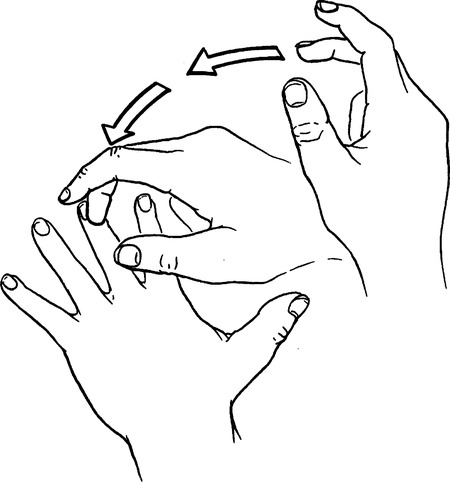

D Percussion is the production of audible and tactile vibrations over the chest by tapping the chest wall (Figure 18-1).

1. If lung tissue is normal, percussion produces a moderately low-pitched sound.

2. The presence of increased air in the thoracic cavity produces a lower-pitched, more muffled drumlike sound, frequently referred to as hyperresonance.

3. Decreased air in the thoracic cavity, consolidation, atelectasis, or a pleural effusion causes the percussion note to be higher pitched but dull or flat.

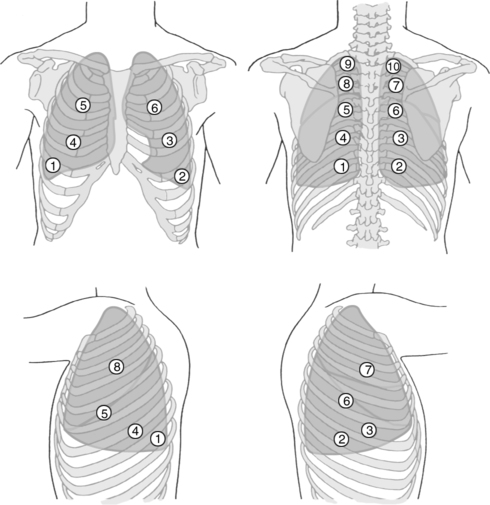

4. Percussion should be performed over all lung fields following a specific pattern as illustrated in Figure 18-2.

E Auscultation is the evaluation of breath sounds with a stethoscope (see Figure 18-2).

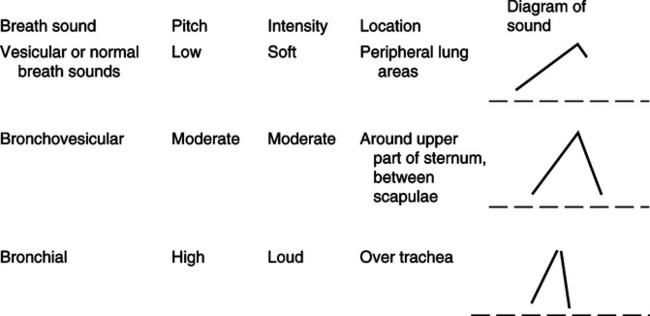

1. Normal breath sounds (Figure 18-3)

a. Over the trachea, the sound is loud with a tubular quality, referred to as bronchial or tracheal breath sounds.

b. Auscultation of the parenchyma reveals a soft muffled sound referred to as vesicular breath sounds. These are usually heard during inspiration but only minimally during exhalation.

c. The sound heard over the airways is termed bronchovesicular. It is softer than bronchial breath sounds and lower in pitch, being heard during inspiration and expiration.

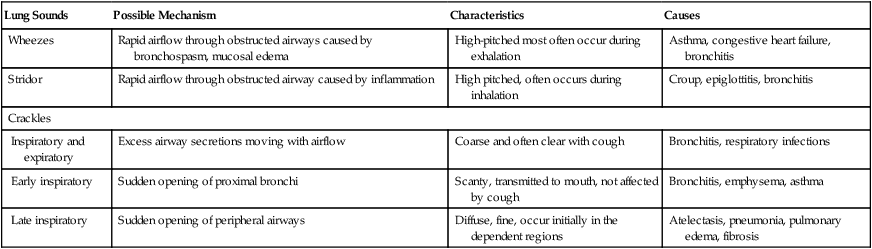

2. Adventitious or abnormal breath sounds (Tables 18-3 and 18-4)

TABLE 18-3

Recommended Terminology for Lung Sounds Versus Terminology in Other Publications

| Recommended Term | Classification | Terms Used in Other Publications |

| Crackles | Discontinuous | Rales |

| Crepitations | ||

| Wheezes | High-pitched, continuous | Sibilant rales |

| Musical rales | ||

| Sibilant rhonchi | ||

| Low-pitched, continuous | Rhonchi | |

| Sonorous rales |

From Wilkins RL, Krier SJ, Sheldon RL: Clinical Assessment in Respiratory Care, ed 4. St. Louis, Mosby, 2000.

TABLE 18-4

Application of Adventitious Lung Sounds

| Lung Sounds | Possible Mechanism | Characteristics | Causes |

| Wheezes | Rapid airflow through obstructed airways caused by bronchospasm, mucosal edema | High-pitched most often occur during exhalation | Asthma, congestive heart failure, bronchitis |

| Stridor | Rapid airflow through obstructed airway caused by inflammation | High pitched, often occurs during inhalation | Croup, epiglottitis, bronchitis |

| Crackles | |||

| Inspiratory and expiratory | Excess airway secretions moving with airflow | Coarse and often clear with cough | Bronchitis, respiratory infections |

| Early inspiratory | Sudden opening of proximal bronchi | Scanty, transmitted to mouth, not affected by cough | Bronchitis, emphysema, asthma |

| Late inspiratory | Sudden opening of peripheral airways | Diffuse, fine, occur initially in the dependent regions | Atelectasis, pneumonia, pulmonary edema, fibrosis |

From Wilkins RL, Krider SJ, Sheldon RL: Clinical Assessment in Respiratory Care, ed 4. St. Louis, Mosby, 2000.

a. Crackles (rales): A discontinuous sound (<20 msec) that is perceived as a wet, crackling, bubbling sound associated with gas moving through liquid. Normally they are heard during:

b. Rhonchi: A continuous sound (>25 msec) that is low in pitch and normally indicative of secretions in large airways. In patients who can successfully mobilize their own secretions, rhonchi clear with coughing.

c. Wheezes: A continuous sound (>25 msec) that is high pitched and normally indicative of bronchospasm or mucosal edema in medium to larger airways. Wheezes do not clear with coughing.

d. Pleural friction rub: A creaking or grating sound as a result of inflamed pleural surfaces rubbing together during breathing.

A During normal breathing the muscles of ventilation consume 5% to 10% of the total oxygen consumed to perform the work of breathing.

B The effort required to perform the work of breathing depends on the following:

1. Airway resistance (increased; increases work)

2. Compliance (decreased; increases work)

3. Respiratory rate (increased; increases work)

4. Tidal volume (increase and decrease may increase work)

C Normally the ventilatory pattern a patient assumes is that which requires the least work.

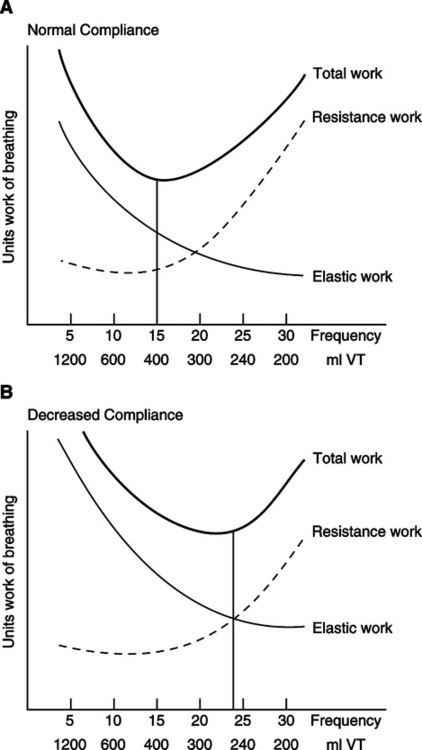

1. Figure 18-4, A, relates the components of the work of breathing to the respiratory rate and tidal volume.

2. Resistance work refers to the amount of work necessary to overcome nonelastic resistance to ventilation. If nonelastic resistance were the only force opposing ventilation, the ideal ventilatory pattern would be a slow rate and a large tidal volume.

3. Elastic work refers to the amount of work necessary to overcome elastic resistance. If elastic resistance were the only force opposing ventilation, a rapid ventilatory rate with a small tidal volume would be ideal.

4. Total work refers to actual work expended with varying ventilatory rates and tidal volumes. Note the ideal rate is approximately 12 to 18 breaths/min with an ideal tidal volume of approximately 6 ml/kg predicted body weight.

5. Figure 18-4, B, illustrates the effect an increase in elastic work has on ventilatory pattern.

a. Because elastic resistance to ventilation has increased, the least amount of work is accomplished at a high ventilatory rate and a small tidal volume.

b. With most acute pulmonary diseases there is an increase in elastic work; therefore, ventilatory rates increase and tidal volumes decrease.

6. If resistance work were increased, the total work curve in Figure 18-4, A, would shift to the left.

a. The ideal respiratory pattern would produce a slow rate with large tidal volumes. This pattern minimizes the effect of the increased resistance.

b. This would be the ideal ventilatory pattern for patients in asthmatic attacks. However, fear and anxiety frequently result in the opposite pattern (fast and shallow) being assumed.

7. Refer to Chapter 5 for quantification of work of breathing.

A Ventilatory reserve is the ability of the organism to respond to increased levels of cardiopulmonary stress.

B During normal breathing, the efficiency of the ventilatory muscles is poor. Approximately 90% of the oxygen consumed to perform the work of breathing is lost as heat.

C The efficiency of the ventilatory muscles is further reduced with chronic pulmonary disease and with an increased minute ventilation.

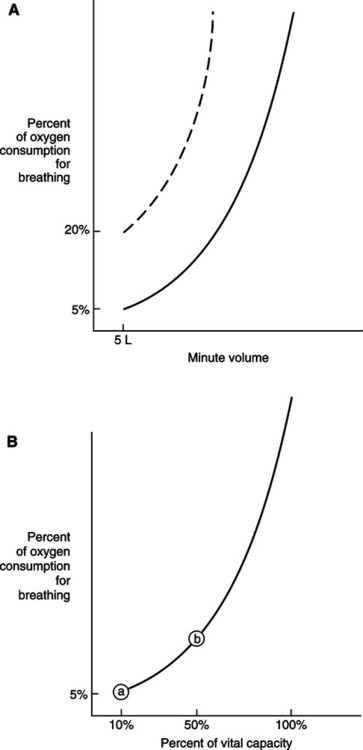

D Figure 18-5, A, depicts the relationship between minute volume and percentage of oxygen consumed for breathing in patients without chronic pulmonary disease (solid line) and patients with chronic pulmonary disease (dotted line).

1. The percentage of oxygen consumed for breathing markedly increases as minute volume increases.

2. In patients with chronic pulmonary disease the percentage of oxygen consumed for breathing at basal level is already increased (20%). With increased minute volume there is a tremendous increase in oxygen consumption. These patients have markedly lower reserves than patients without chronic pulmonary disease.

E Figure 18-5, B, illustrates the relationship between percentage of oxygen consumed for breathing and the percentage of the vital capacity (VC) that is the tidal volume.

VIII Vital Capacity/Maximum Inspiratory Pressure

A A normal VC is approximately 70 to 90 ml/kg of ideal body weight.

B VCs are frequently used as an estimate of the patient’s ventilatory reserve.

C If the VC is >15 ml/kg of ideal body weight, it is assumed that the individual has the capability to respond to increased levels of cardiopulmonary stress.

D However, if the VC is <10 ml/kg, prolonged sustained spontaneous ventilation is questionable. This individual has virtually no reserves.

E At VCs between 10 and 15 ml/kg, reserves are marginal, and appropriate monitoring should be instituted.

F Maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP) is also a parameter used to assess ventilatory reserves.

G If the MIP is more negative than -30 cm H2O in a 20-second period and the patient has normal lungs and is recovering from anesthesia, neuromuscular or neurologic disease, or an overdose, sustained spontaneous ventilation is probable.

H In patients with chronic pulmonary disease or acute respiratory failure associated with multiorgan system failure, the use of a -30 cm H2O range for MIP becomes less reliable.

1. In this population, MIP or VC values provide a daily guide to ventilatory muscle capability but are unreliable as a specific indicator of spontaneous ventilatory capability.

2. The measurement of MIP before and after weaning trials provides information on the development of exhaustion. A lower value after a weaning trial compared with initial values indicates exhaustion and an inability to continue spontaneous breathing.

I During the measurement of MIP, the diaphragm must be at its resting level for maximum performance. Thus the greater the length of the diaphragmatic muscle fibers (smaller lung volume), the greater their contractile force.

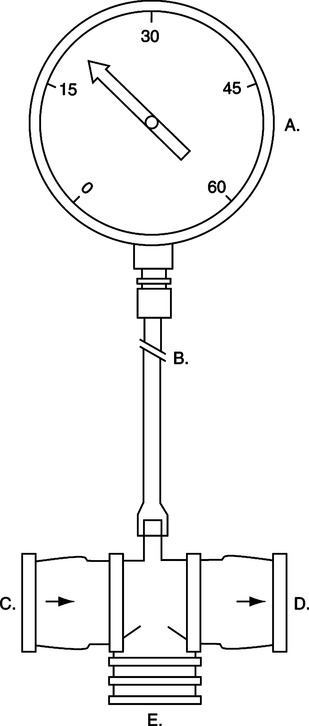

1. In the intensive care unit, evaluation of MIP is difficult if a one-way valve system is not used (Figure 18-6).

2. The use of a one-way valve allows the patient to exhale after each attempted inspiration, resulting in a lower lung volume and greater force generation.

3. Normally inspiratory occlusion is maintained for 20 seconds unless adverse reaction occurs.

4. MIP generally should be measured only in patients with stable cardiopulmonary status who can withstand the stress.

IX Rapid Shallow Breathing Index

A Normally the relationship between respiratory rate and tidal volume in liters is approximately 20 to 60 in the average adult.

B This relationship has been used to determine whether a patient is ready to be discontinued from ventilatory support.

C In critically ill patients a rapid shallow breathing index (RSBI) <105 indicates a high probability of being able to breathe unassisted.

D An RSBI ≥105 indicates ventilatory support is still required.

E It is critical that the RSBI be determined the same way it was studied if it is to be maximally predictive.

1. Patient is disconnected from the ventilator.

2. Allowed to breathe room air unsupported.

3. Respiratory rate is counted for a full minute.

4. Tidal volume is measured with a pneumotachograph and mask or mouthpiece for a full minute and the average determined.

5. Respiratory rate is then divided by average tidal volume expressed in liters.

X Assessment of Peripheral Perfusion

A Adequacy of peripheral perfusion can be estimated by:

1. Confusion, agitation, and disorientation are all signs of cerebral hypoxia that can be caused by decreased oxygen carriage or decreased cerebral perfusion.

2. Somnolence and drowsiness are signs of increased arterial Pco2 levels.

1. Normal urinary output is approximately 40 to 60 ml/hr.

2. Decreased urinary output is frequently a sign of decreased peripheral perfusion.

D Capillary refill decreases as peripheral perfusion decreases.

E Skin turgor also decreases as peripheral perfusion decreases.

G Thready, faint, or distant peripheral pulses are noted as peripheral perfusion decreases.

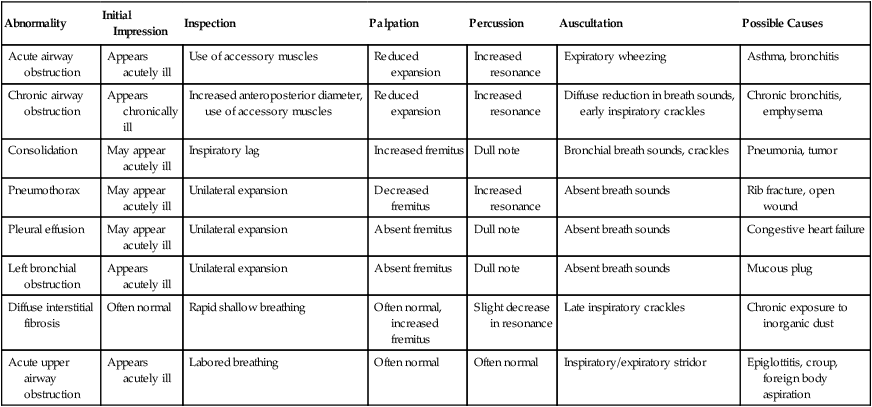

XI Physical Signs Associated with Common Abnormal Pulmonary Pathology (Table 18-5)

TABLE 18-5

Physical Signs of Pulmonary Abnormalities

| Abnormality | Initial Impression | Inspection | Palpation | Percussion | Auscultation | Possible Causes |

| Acute airway obstruction | Appears acutely ill | Use of accessory muscles | Reduced expansion | Increased resonance | Expiratory wheezing | Asthma, bronchitis |

| Chronic airway obstruction | Appears chronically ill | Increased anteroposterior diameter, use of accessory muscles | Reduced expansion | Increased resonance | Diffuse reduction in breath sounds, early inspiratory crackles | Chronic bronchitis, emphysema |

| Consolidation | May appear acutely ill | Inspiratory lag | Increased fremitus | Dull note | Bronchial breath sounds, crackles | Pneumonia, tumor |

| Pneumothorax | May appear acutely ill | Unilateral expansion | Decreased fremitus | Increased resonance | Absent breath sounds | Rib fracture, open wound |

| Pleural effusion | May appear acutely ill | Unilateral expansion | Absent fremitus | Dull note | Absent breath sounds | Congestive heart failure |

| Left bronchial obstruction | Appears acutely ill | Unilateral expansion | Absent fremitus | Dull note | Absent breath sounds | Mucous plug |

| Diffuse interstitial fibrosis | Often normal | Rapid shallow breathing | Often normal, increased fremitus | Slight decrease in resonance | Late inspiratory crackles | Chronic exposure to inorganic dust |

| Acute upper airway obstruction | Appears acutely ill | Labored breathing | Often normal | Often normal | Inspiratory/expiratory stridor | Epiglottitis, croup, foreign body aspiration |

From Wilkins RL, Krider SJ, Sheldon RL: Clinical Assessment in Respiratory Care, ed 4. St. Louis, Mosby, 2000.

XII Laboratory Assessment in Cardiopulmonary Disease

1. Complete red blood cell count (CBC)

a. Red blood cell (RBC) count (normal levels)

2. Anemia: A below-normal quantity of hemoglobin, RBC count, or hematocrit and greatly decreases oxygen-carrying capacity. It may be a result of:

3. Polycythemia: An increase in hemoglobin, RBC count, or hematocrit. It may result from:

4. Abnormalities in WBC count and their differential are a result of infection, allergic reaction, or leukemia.

a. An increase in overall WBC count (i.e., leukocytosis) is normally noted in bacterial infections.

b. A decrease in overall WBC count (i.e., leukopenia) is normally noted in leukemia, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.

c. Neutrophilia (increased neutrophils): A common response to stress and the body’s first response to:

d. A leftward shift of the neutrophils: Increased levels of bands (immature neutrophils) as a result of stress. The greater the stress, the greater the percent bands.

e. Eosinophilia: An increase in the number of eosinophils, usually a result of:

f. Lymphocytosis: An increase in the number of lymphocytes, usually a result of a viral infection.

g. Monocytosis: An increase in the number of monocytes, usually a result of:

h. Basophilia: An increase in the number of basophiles usually seen in:

a. Platelets are necessary for normal coagulation of blood. If the platelet count is low, small skin hemorrhages are noted:

b. Platelet counts are reduced by:

c. An increase in platelets may be a result of:

d. Increased platelet levels increase the likelihood of thrombosis (blood clots).

1. Four distinct tests generally are used to evaluate the tendency of blood to clot.

2. Bleeding time: Evaluates the ability of small skin vessels to constrict and evaluates the function of platelets. Normal time is up to 6 minutes.

3. APTT: Evaluates the amount of time it takes plasma to form a fibrin clot once the body’s intrinsic clotting pathways are activated. Normal time is 32 to 51 seconds.

4. PT: Evaluates the amount of time it takes extrinsic blood factors to form a clot once activated. Normal PT is 12 to 15 seconds.

5. All times are lengthened during hemophilia.

C Electrolytes (see Chapter 14)

D Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels and urinalysis (see Chapter 13).