Chapter 2 Clinical Approach to the Patient

Obstetric and Gynecologic Evaluation

Obstetric and Gynecologic Evaluation

In few areas of medicine is it necessary to be more sensitive to the emotional and psychological needs of the patient than in obstetrics and gynecology. By their very nature, the history and physical examination may cause embarrassment to some patients. The members of the medical care team are individually and collectively responsible for ensuring that each patient’s privacy and modesty are respected while providing the highest level of medical care. Box 2-1 lists the appropriate steps for the clinical approach to the patient.

Obstetric History

Obstetric History

PREVIOUS PREGNANCIES

Each prior pregnancy should be reviewed in chronologic order and the following information recorded:

Diagnosis of Pregnancy

Diagnosis of Pregnancy

SIGNS OF PREGNANCY

The signs of pregnancy may be divided into presumptive, probable, and positive.

Gynecologic History

Gynecologic History

Gynecologic Physical Examination

Gynecologic Physical Examination

GENERAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Breasts

The breast examination is particularly important in gynecologic patients (see Chapters 29 and 31).

Abdomen

Abdominal tenderness must be determined by placing one hand flat against the abdomen in the nonpainful areas initially, then gently and gradually exerting pressure with the fingers of the other hand (Figure 2-1). Rebound tenderness (a sign of peritoneal irritation), muscle guarding, and abdominal rigidity should be gently elicited, again first in the nontender areas. A “doughy” abdomen, in which the guarding increases gradually as the pressure of palpation is increased, is often seen with a hemoperitoneum.

PELVIC EXAMINATION

Speculum Examination

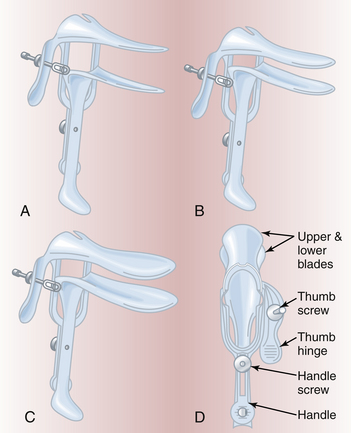

The vagina and cervix should be inspected with an appropriately sized bivalve speculum (Figure 2-2), which should be warmed and lubricated with warm water only, so as not to interfere with the examination of cervical cytology or any vaginal exudate. After gently spreading the labia to expose the introitus, the speculum should be inserted with the blades entering the introitus transversely, then directed posteriorly in the axis of the vagina with pressure exerted against the relatively insensitive perineum to avoid contacting the sensitive urethra. As the anterior blade reaches the cervix, the speculum is opened to bring the cervix into view. As the vaginal epithelium is inspected, it is important to rotate the speculum through 90 degrees, so that lesions on the anterior or posterior walls of the vagina ordinarily covered by the blades of the speculum are not overlooked. Vaginal wall relaxation should be evaluated using either a Sims’ speculum or the posterior blade of a bivalve speculum. The patient is asked to bear down (Valsalva’s maneuver) or to cough to demonstrate any stress incontinence. If the patient’s complaint involves urinary stress or urgency, this portion of the examination should be carried out before the bladder is emptied.

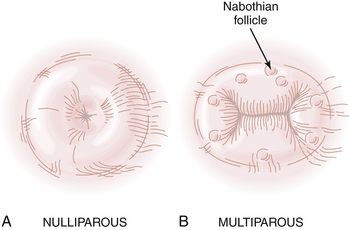

The cervix should be inspected to determine its size, shape, and color. The nulliparous patient generally has a conical, unscarred cervix with a circular, centrally placed os; the multiparous cervix is generally bulbous, and the os has a transverse configuration (Figure 2-3). Any purulent cervical discharge should be cultured. Plugged, distended cervical glands (nabothian follicles) may be seen on the ectocervix. In premenopausal women, the squamocolumnar junction of the cervix is usually visible around the cervical os, particularly in patients of low parity. Postmenopausally, the junction is invariably retracted within the endocervical canal. A cervical cytologic smear (Papanicolaou, or Pap, smear) should be taken before the speculum is withdrawn. The exocervix is gently scraped with a wooden spatula, and the endocervical tissue is gently sampled with a Cytobrush.

Bimanual Examination

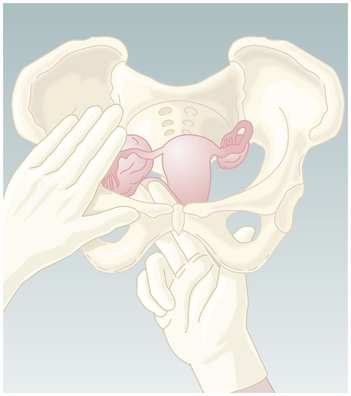

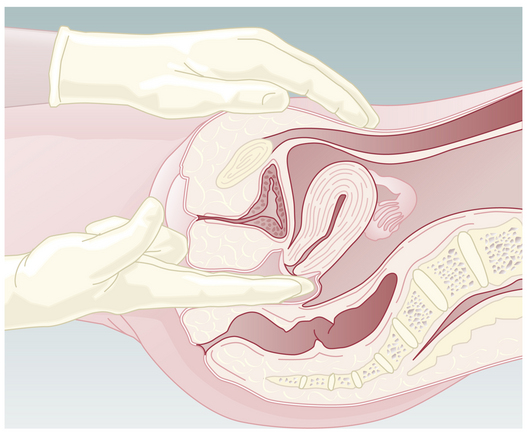

The uterus is evaluated by placing the abdominal hand flat on the abdomen with the fingers pressing gently just above the symphysis pubis. With the vaginal fingers supinated in either the anterior or the posterior vaginal fornix, the uterine corpus is pressed gently against the abdominal hand (Figure 2-4). As the uterus is felt between the examining fingers of both hands, the size, configuration, consistency, and mobility of the organ are appreciated. If the muscles of the abdominal wall are not compliant or if the uterus is retroverted, the outline, consistency, and mobility must be determined by ballottement with the vaginal fingers in the fornices; in these circumstances, however, it is impossible to discern uterine size accurately.

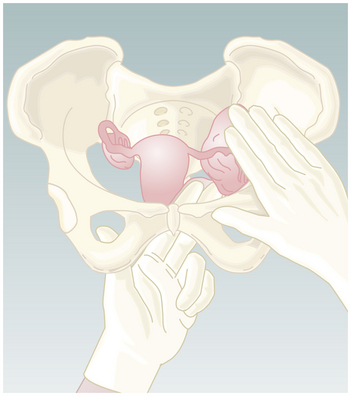

By shifting the abdominal hand to either side of the midline and gently elevating the lateral fornix up to the abdominal hand, it may be possible to outline a right adnexal mass (Figure 2-5). The left adnexa are best appreciated with the fingers of the left hand in the vagina (Figure 2-6). The examiner should stand sideways, facing the patient’s left, with the left hip maintaining pressure against the left elbow, thereby providing better tactile sensation because of the relaxed musculature in the forearm and examining hand. The pouch of Douglas is also carefully assessed for nodularity or tenderness, as may occur with endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or metastatic carcinoma.

FIGURE 2-5 Bimanual examination of the right adnexa. Note that fingers of the right hand are in the vagina.

RECTAL EXAMINATION

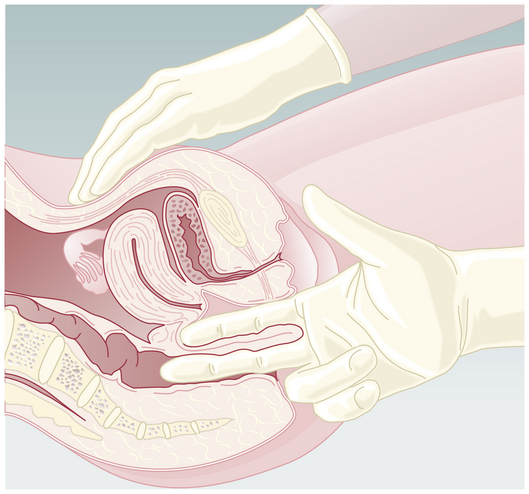

A rectovaginal examination is helpful in evaluating masses in the cul-de-sac, the rectovaginal septum, or adnexa. It is essential in evaluating the parametrium in patients with cervical cancer. Rectal examination may also be essential in differentiating between a rectocele and an enterocele (Figure 2-7).

Patients with Special Needs

Patients with Special Needs

GENITAL AMBIGUITY

Dealing with genital ambiguity in the newborn requires a coordinated and timely response. The family’s psychological well-being must be addressed because they must feel confident in the gender identity of their child. Ambiguity can result from masculinization of a female child due to exogenous hormone ingestion or maternal or fetal overproduction of androgen. It may also result from incomplete virilization of a male infant, hormonal insensitivity, gonadal dysgenesis, or chromosomal anomalies (see Chapters 31 and 32). When assessing an infant with ambiguous genitals, fluid and electrolyte balance should be monitored and blood drawn for 17-hydroxyprogesterone and cortisol to rule out 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Life-threatening illness may be missed in children with the salt-losing form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (see Chapter 32).

VAGINAL BLEEDING IN THE PREPUBERTAL CHILD

Precocious puberty (see Chapter 31) may present with vaginal bleeding, although most commonly other evidence of maturation will have preceded the bleeding and will be evident on examination. At the very least, a pale, estrogenized vaginal epithelium will be seen, and cytologic analysis of the vagina will confirm the hormonal effect. Transient precocious puberty may occur in response to a functional ovarian cyst, and vaginal bleeding may be triggered by the spontaneous resolution of the cyst. Exogenous hormonal exposure should be considered because children have been known to ingest birth control pills. Ovarian tumors resulting in pseudoprecocious puberty should be ruled out.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The initial reproductive health visit. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 335. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;100:1413-1416.

Cope Z. The Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen. London: Oxford Medical Publications; 2001.

Lewis M.A., Mickman J.L. Approach to the patient with developmental disabilities. In: Pregler J.P., DeCherney A.H., editors. Women’s Health: Principles and Clinical Practice. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker, 2002.

Pham T. Approach to the geriatric patient. In: Pregler J.P., DeCherney A.H., editors. Women’s Health: Principles and Clinical Practice. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker, 2002.

Wilkes M.S., Anderson M. Approach to the adolescent patent. In: Pregler J.P., DeCherney A.H., editors. Women’s Health: Principles and Clinical Practice. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker, 2002.

Obstetric Physical Examination

Obstetric Physical Examination

The Geriatric Patient

The Geriatric Patient Patients with Disabilities

Patients with Disabilities