1 Clinical approach to cancer patients

Introduction

A suspicion of cancer or diagnosis of cancer is the beginning of a difficult journey. In many ways it is like climbing a mountain for the first time; a journey filled with uncertainty and challenges which carries no guarantees (Figure 1.1). Patients often carry additional anxieties if there have been perceived delays so that a knowledge of warning signs of cancer and an understanding of referral and treatment is essential for any healthcare professional.

Patients presenting to their primary care physician with warning signs of cancer (Box 1.1) should be referred to a specialist centre for an urgent evaluation. In the UK and many parts of the World, cancer treatment is organized around a multidisciplinary team which consists of physicians, surgeons, cancer specialists, radiologists, pathologists and clinical nurse specialists. Many investigations for suspected cancer are done either in ‘one-stop’ (e.g. for breast cancer) or ‘two-stop’ clinics (e.g. lung cancer) to expedite diagnosis and treatment.

Investigations for a suspected cancer

Diagnostic investigations

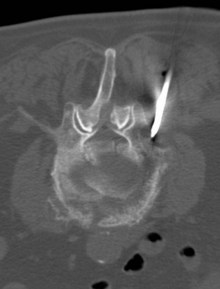

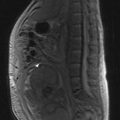

Diagnostic investigations are undertaken in a logical order, with blood tests including relevant tumour markers and simple imaging, and proceed to the diagnostic imaging of choice for particular tumour types. Imaging helps to determine local and distant metastatic staging. Confirmation of the diagnosis can be obtained by cytology or biopsy. Many tumours require biopsy for further characterization and immunohistochemical assessment. Biopsies can be obtained by core biopsies, and guided biopsies using imaging or endoscopic visualization (Figure 1.2). All patients need a definite histological diagnosis if specific cancer treatment is contemplated. Rarely, treatment can be undertaken when the radiological appearance and tumour markers are typical (e.g. choriocarcinoma, germ cell tumours).

Staging investigations

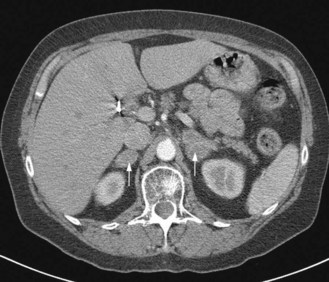

Once the histological diagnosis is established, further investigations are undertaken to stage the cancer. The choice of investigation depends on the primary and pattern of metastasis. For example, the common sites of metastasis in lung cancer are regional lymph nodes, adrenals and liver; hence all patients with a lung cancer have CT scan of chest and abdomen (Figure 1.3). All patients who are planned to undergo curative treatment, particularly an extensive surgical resection, need additional investigations to assess their suitability for radical treatment. Functional imaging is more sensitive than anatomical imaging in detecting distant metastasis (e.g. PET scan staging alters conventional staging in up to 25% of patients). Endoscopic ultrasound and thoracoscopy and laparoscopy are also used in staging in appropriate situations (Chapters 9, 11).

Staging

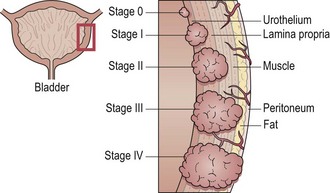

The purpose of staging is to assess the extent of disease, choose the appropriate treatment and to assess likely outcome of the disease. Staging is also important in the comparison of results between treatment centres. The TNM system has been developed for many cancers. TNM staging denotes tumour, node and metastatic status. T staging is generally based on the size of the tumour (usually according to defined size criteria, e.g. in breast cancer) or depth of invasion in hollow organs (e.g. oesophageal cancer, bladder cancer) or local spread to neighbouring organs or subsites (e.g. supraglottic cancer) (Figure 1.4). N staging is based on pattern of spread along the lymphatic chain, or number of nodes involved or size of nodes involved. It may be clinical or pathological. M1 denotes distant metastasis. Composite staging involves grouping various T, N and M combinations into 4 stages and each site has different stage grouping (e.g. see p. 80). Other descriptors of TNM staging are shown in Box 1.2. Other cancers are staged by slightly different systems such as FIGO for many gynaecological cancers (Chapters 13, p. 197).

Box 1.2

TNM staging descriptors

Prefix

Consultation with patients and breaking the news

When patients attend oncology clinics many of them may have some idea about the details of their cancer and a rough outline of their further management. However, most patients are in shock and may take a long time to come to terms with a diagnosis of cancer. This gets particularly difficult for an inquisitive patient, who will search for more information on the internet and some of the information overload can add to the anxiety. A clinician role is to help the patient to cope with the situation, and give them clear directions on further management and aim (Box 1.3).

Box 1.3

Tips on consultation

Dos

Don’ts

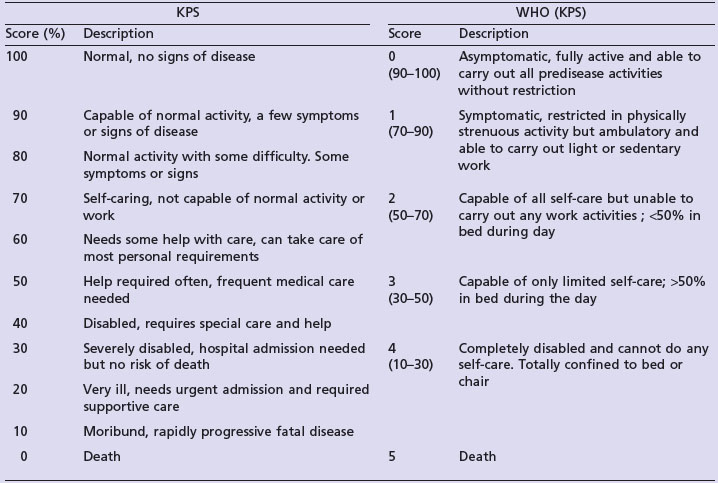

Assessing fitness for treatment

Performance status (PS): Performance status helps to quantify the physical well-being of patients and helps to determine optimal treatment, make treatment modifications (including dose modification of chemotherapy) and to measure the intensity of supportive care required. It should be clearly documented at the beginning and throughout treatment. There are a number of scoring systems and the two most commonly used are Karnofsky performance status (KPS) and WHO score (Table 1.1). Patients are generally eligible for curative treatment only if PS is 0–1, palliative anticancer treatment when PS is 0–2 and generally no anticancer treatment is given if PS 3–4. However, in certain situations, when the disease is very responsive to treatment and rapid deterioration is due to the current disease process, modified curative treatment is considered (e.g. germ cell tumours). If performance status deteriorates rapidly during anticancer treatment, treatment is either stopped or modified.

Follow-up during treatment

Follow-up during treatment is to assess response to treatment, monitor toxicity and modify further treatment. Toxicity should be monitored alongside treatment so that patients on a 3 weekly cycle of chemotherapy will be seen every 3 weeks prior to each treatment to modify the dose or adjust supportive treatments. For patients who have had significant toxicities on a previous cycle, they may be seen in between the cycle dates. Patients undergoing radiotherapy will often be seen at least once throughout their treatment to assess acute toxicities and prescribe supportive measures as necessary.

Support during treatment

The potential sources of this support can be in the form of documents from helpful websites or organizations, local cancer support groups, and named key workers such as specialist nurses or Macmillan nurses. It should be emphasized at the start of diagnosis and treatment that it is natural to require the help of others at some point in the journey and that it will only help their overall outcome. The special needs of children diagnosed with cancer and their family is discussed on p. 320.

Genetic screening

Patients with a suspected genetic component to their cancer need referral to a clinical genetics department. Chapter 5 (p. 45) deals with the recommendations for referral to clinical genetics and further management for the patient and their family.

Follow-up after treatment and management of recurrence

Almost all patients who have been treated with curative intent need some regular follow-up to detect an early potentially curable recurrence and a second cancer. The frequency and mode of follow-up depend on the pattern of recurrence of individual cancers, which are dealt with individually. It is still debatable whether early detection of a metastatic recurrence improves overall survival in most cancers.

Beyond cure and survivorship

For many patients treatment will be possible and they will succeed in climbing the mountain of diagnosis, treatment and its complications (Figure 1.5). However the long-term impact of this on their lives must not be underestimated and many patients feel at their most lost at the end of treatment or when follow-up is discontinued (see also p. 58, late effects). An understanding of this process will help facilitate any further care that is necessary to return them to a functional life.