30 Clinical and performance-based assessment

The importance of clinical assessment

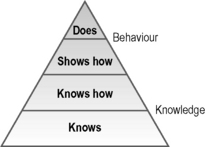

The assessment of competence can be distinguished from performance assessment. Tests of competence, such as the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), demonstrate in a controlled situation what an examinee is capable of doing. Performance assessment tools such as record analysis or multi-source feedback assess what the individual does in practice. The Miller pyramid provides a framework for assessment with the bottom of the pyramid being the assessment of knowledge and the higher levels of the pyramid being the assessment of performance (Fig. 30.1).

Considerations in clinical assessment

The patient

There are benefits to be gained from the use of a range of patient representations in the clinical examination. The choice of patient representation will be influenced by what is being assessed, the level of standardisation required, the required realism or fidelity and the local logistics including the availability and relative costs associated with the use of real patients and trained simulated patients (Collins and Harden 1998).

Simulated patients

Difficulties in standardising real patients and a lack of availability in some situations led to the development of simulated or standardised patients. These have been used for assessment as well as teaching. The simulated patient, as described in Chapter 25, is usually a lay person who has undergone various levels of training in order to provide a consistent clinical scenario. The examinee interacts with the simulated patient in the same way as if they were taking a history, examining or counselling a real patient. Simulated patients are used most commonly to assess history taking and communication skills or physical examination where no abnormality is found. Simulated patients have also been used to simulate a range of physical findings including, for example, different neurological presentations. The term ‘standardised patient’ has been used to indicate that the person has been trained to play the role of the patient consistently and according to specific criteria.

Simulators and models

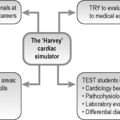

Simulators, from the very basic models used to assess skills such as skin suturing to the more complex interactive whole-body manikins such as SimMan, have been used increasingly in medical training as outlined in Chapter 25. They have an important role to play in assessment. The Harvey cardiac manikin, for example, has been used at an OSCE station to assess skills in cardiac auscultation. Simulators are valuable to assess procedural and practical skills including the insertion of intravenous lines, catheterisation and endoscopy technique. While simulators have played a key role in competence assessment in other fields, notably with airline pilots, simulators have been slow to make an impact in assessment in medicine. The situation has changed rapidly and such devices now play a prominent role in clinical assessment. Indeed in some instances surgeons are allowed to perform a procedure in clinical practice only after they have demonstrated competence on a simulator.

The examiner

A student’s profile

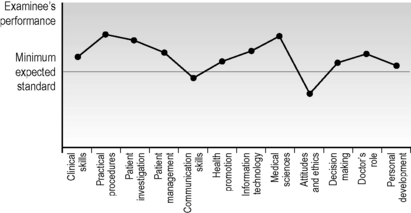

A wide range of different learning outcomes or competencies including clinical skills, practical procedures, decision making and problem solving, collaboration and team working and professionalism and attitudes is assessed in a clinical examination. It makes little sense simply to allocate a percentage score for each component and then to sum these to produce a total mark of, for example, 62%. Excellence in carrying out an examination or practical procedure should not compensate for unprofessional behaviour or an inappropriate attitude. The answer is not to agonise over the relative importance of each element of competence and the allocation of a percentage for that element but to produce a competence profile for the examinee. This indicates for each candidate, as shown in Figure 30.2, the domains where their performance is satisfactory or perhaps excellent and those domains or competencies where their performance falls short of what is expected.

Feedback

The provision of feedback to the examinee is an important part of a clinical assessment. As discussed in Chapter 2, this should be specific, non-evaluative and timely. It is an essential element of ‘assessment for learning’ and should guide the learner in their further studies. It is important that when the assessment process is planned, time is allowed for the provision of feedback. The OSCE can be considered as an example of the different approaches that can be adopted:

• Following an OSCE, students’ checklists and ratings sheets for each station can be returned to the examinee with the examiner’s comments attached.

• Following an OSCE, a meeting with the teacher can be scheduled and the examination is discussed with individuals or the class as a whole.

• During an OSCE, time can be allocated at the end of each station for the provision of feedback from the examiner to the examinee.

• After completion of a station, the examinees review at the following station their own performance at the previous station as recorded on the examiner’s checklist and compare this with a model performance as shown on a video recording.

Approaches to clinical and performance assessment

The objective structured long examination record (OSLER)

In the traditional long case, the examinee takes a history and examines a patient over a period of up to an hour unobserved by the examiner. Following this the examiner meets with the student and over a 20–30-minute period discusses the patient and the examinee’s findings and conclusions. As a replacement for the ‘long case’ component of a clinical examination, the OSLER was proposed as a more objective and valid assessment of the student’s clinical competence (Gleeson 1997).

• history taking scored in relation to pace and clarity of presentation, communication skills, systematic approach and the establishment of the case facts

• physical examination rated in relation to a systematic approach, examination technique, and the establishment of the correct physical findings

• the ability to determine appropriate investigations for the patient

• the examinee’s views on the management of the patient

• the clinical acumen and overall ability to identify and present a satisfactory approach to tackling the patient’s problems.

The objective structured clinical examination (OSCE)

1. The task can be specified so that it can be completed in 5 minutes.

2. The task can be spread over two linked stations with the first part of the task, for example assessing a patient’s record, undertaken at the first station and the subsequent task of counselling the patient assessed at the following station.

3. A station may be duplicated in the circuit to allow students to spend double the set time at the station. This may be useful for a history taking station.

The content of the examination together with the competencies to be tested is carefully planned on a blueprint in advance of the OSCE. This ensures that the examination tests a range of competencies in relation to different aspects of medical practice. Examples of the types of stations that can be included in an OSCE are given in Appendix 5.

Reflect and react

1. The assessment of clinical competence is a central issue in medical education and whatever your role as a teacher, you should be aware of the different approaches and tools available.

2. You may find yourself responsible for the organisation of an OSCE. The OSCE is a flexible tool. See a couple in action then design one to suit your own needs.

3. You may have to serve as an examiner in an OSCE or be the person responsible for providing students with feedback on their performance. Your role may be to advise students or trainees who are about to sit an OSCE as to how best to prepare for it. Ensure that you are familiar with the examination details.

4. Performance assessment in the work place is particularly challenging. The examiner and examinee both need to be committed to its success. Think about how you might distinguish between competence and performance in your trainees.

Boursicot K., Etheridge L., Setna Z., et al. Performance in assessment: consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa conference. Med. Teach.. 2011;33:370-383.

The conclusions of a group of experts in the area.

Boursicot K.A.M., Roberts T.E., Burdick W.P. Structured assessments of clinical competence. In: Swanwick T., editor. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence,Theory and Practice. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:246-258.

Practical advice on planning, running and scoring an OSCE.

Collins J.P., Harden R.M. The use of real patients, simulated patients and simulators in clinical examinations. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 13. Med. Teach.. 1998;20:508-521.

Gleeson F. Assessment of clinical competence using the Objective Structured Long Examination Record (OSLER). AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 9. Med. Teach.. 1997;19:7-14.

A description of how the long case can be improved in a clinical examination.

Harden R.M., Gleeson F.A. ASME Medical Education Guide No. 8. Assessment of Medical Competence Using an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE). Edinburgh: ASME; 1979.

An early description of the OSCE but still with much relevance today.

Hill F., Kendall K. Adopting and adapting the mini-CEX as an undergraduate assessment and learning tool. The Clinical Teacher. 2007;4:244-248.

How the Mini-CEX can be used in undergraduate education.

Norcini J., Burch V. Work-place Based Assessment as an Educational Tool. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 31. Dundee: AMEE, 2007.

A description of the range of tools used in work place based assessment.

Gronlund N.E., Waugh C.K. Assessment of Student Achievement. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson; 2009.

Chapter 9 in this classic text provides an overview of performance assessment.

Holmboe E.S., Hawkins R.E. Practical Guide to the Evaluation of Clinical Competence. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

A more detailed account of assessment of clinical competence.

Norcini J., Holmboe E. Work-based assessment. In Cantillon P., Wood D., editors: ABC of Learning and Teaching in Medicine, second ed., Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. (Chapter 11)

An introduction to work-based assessment.

Tekian A., McGuire C.H., McGaghie W.C. Innovative Simulations for Assessing Professional Competence: From Paper-and-Pencil to Virtual Reality. University of Illinois at Chicago Department of Medical Education; 1999.