Chapter 35 Climacteric

MENOPAUSE AND PERI- AND POSTMENOPAUSE∗

Hormonal Changes

Hormonal Changes

Menopause rarely occurs as a sudden loss of ovarian function. For some years before menopause, the ovary begins to show signs of impending failure. Anovulation becomes common, with resulting unopposed estrogen production and irregular menstrual cycles (see Chapter 33). On occasion, heavy menses, endometrial hyperplasia, and increasing mood and emotional changes may occur. In some women, hot flashes (or flushes) and night sweats begin well before menopause is reached. These perimenopausal symptoms may last 3 to 5 years before there is complete loss of menses and postmenopausal levels of hormones are reached.

Ovarian Senescence

Ovarian Senescence

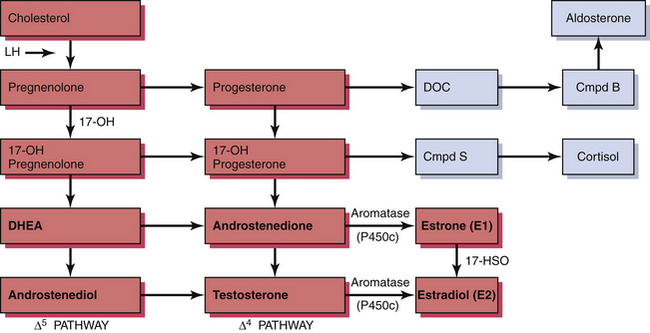

The ovary produces a sequence of hormones during a normal menstrual cycle. Under the influence of luteinizing hormone (LH), cholesterol from the liver is used to produce the androgens androstenedione and testosterone in the theca cells of the ovarian follicle. They, in turn, are converted in the granulosa cells immediately surrounding the oocytes into estrogen. Following ovulation, the luteal cells (luteinized granulosa cells) manufacture and secrete progesterone as well as estrogen. The synthesis of these sex hormones depends on the presence of viable follicles and ovarian stroma and the production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and LH in adequate amounts to induce their biosynthetic activity. The ovarian and adrenal (for comparison) steroid biosynthetic pathways are depicted in Figure 35-1.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical Manifestations

Loss of estrogen is associated with urogenital atrophy and osteoporosis (Table 35-1). Although postmenopausal women have a higher incidence of heart disease and of cancer, the relationship between these adverse events and reduced endogenous estrogen production, as well as the effects of hormonal therapy on them, remains unclear and controversial.

| Symptoms (early) |

Ovarian Hormone Therapy

Ovarian Hormone Therapy

A number of large observational cohort and case-control studies suggested ovarian hormone therapy might prevent or delay the onset of arteriosclerotic heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease through a number of diverse mechanisms. On the other hand, observational studies have raised concerns about ovarian hormone therapy and the risks for venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Although observational studies provide useful information, they are subject to several sources of bias. Table 35-2 lists some of the biases that may occur during observational studies.

TABLE 35-2 SOME OF THE INHERENT BIASES IN OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

| Selection bias | Hormone therapy users may be different from nonusers in terms of behaviors and disease risk. |

| Prescribing bias | Only well women are given hormone therapy. |

| Prevention bias | Monitoring and treatment are more intensive in women on hormone therapy. |

| Compliance bias | Women with greater adherence (even to placebo) have better outcomes. |

| Recall bias | Women who develop a disease have a better recollection of treatments taken. |

| Prevalence-incidence bias | Early adverse effects of hormone therapy not observed if user dies before becoming part of cohort. |

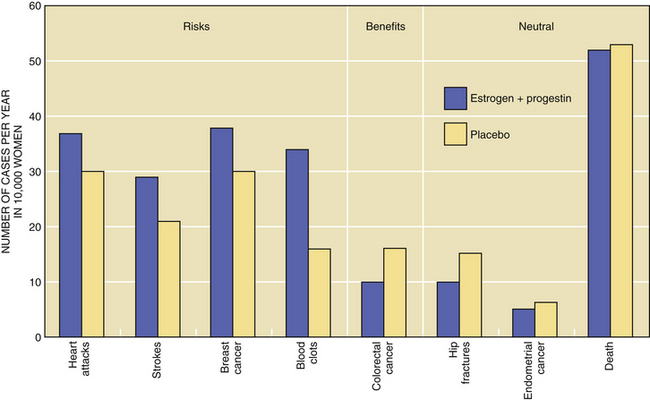

Randomized controlled trials tend to minimize the biases of observational studies. However, they are difficult and time-consuming to do when the conditions being observed are relatively uncommon. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study attempted to sort out the risks and benefits of ovarian hormone therapy. More than 16,000 women were entered into one arm of the study comparing a combined preparation of conjugated estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate with placebo. After 5 years of follow-up, this combined ovarian hormone arm was halted in July 2002. The previously reported protection from osteoporotic fracture was confirmed by the WHI study. In addition, a 37% reduction in the rate of colorectal cancer was found. This would result in six fewer cases of colorectal cancer (10 vs 16) per 10,000 women per year. Combined ovarian hormone use, however, was found to increase the risks for coronary artery disease events (by 29%), stroke (by 41%), thromboses (by 100%), and breast cancer (by 26%). Although most of the risks increased after 1 to 2 years of use, increased risk for breast cancer became apparent only after 4 years of use. There was no significant increase in death rates between treatment and placebo groups (Figure 35-2). Contrary to several previous studies, the WHI found an overall harmful rather than protective effect on cognitive decline and dementia.

FIGURE 35-2 Disease rates for women taking estrogen plus progestin or placebo.

(Data from the Women’s Health Initiative Study Group, 2002.)

A large observational cohort study, the Million Women Study (MWS), is addressing the risks and benefits of hormone therapy after menopause. More than 1 million women have been enrolled in the United Kingdom, and thus far no long-term results have been fully analyzed or reported. After a little more than 4 years of follow-up, however, the MWS reported an increased breast cancer risk with hormone therapy. Table 35-3 lists these results.

TABLE 35-3 RELATIVE RISKS (CONFIDENCE INTERVALS) OF BREAST CANCER WITH DURATION OF CURRENT USE OF HORMONES

| Duration of Use (yr) | Current Users of Estrogen Only | Current Estrogen and Progestin Users |

|---|---|---|

| <1 | 0.81 (0.55-1.20) | 1.45 (1.19-1.78) |

| 1-4 | 1.25 (1.10-1.41) | 1.74 (1.60-1.89) |

| 5-9 | 1.32 (1.20-1.46) | 2.17 (2.03-2.33) |

| ≥10 | 1.37 (1.22-1.54) | 2.31 (2.08-2.56) |

Data from Speroff L: The Million Women Study and breast cancer. Maturitas 46:1-6, 2003.

Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2003;362:419-427.

North American Menopause Society. Management of postmenopausal osteoporosis: Position statement. Menopause. 2002;9:84-101.

Shifren J.L., Schiff I. Menopause. In: Berek J.S., editor. Berek and Novak’s Gynecology. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &Wilkins; 2007,:1323-1340.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis Management of Ovarian Hormonal Therapy

Management of Ovarian Hormonal Therapy Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Lifestyle Changes and Alternative Treatments for the Climacteric

Lifestyle Changes and Alternative Treatments for the Climacteric