Classification of Ocular Surface Disease

Introduction

The first line of defense is the eyelashes, which collect debris, therefore preventing it from interacting and damaging the surface of the eye. There are roughly 100 lashes in the upper lid and 50 in the lower lid.1 The layers of the eyelid, from superficial to deep, include the skin, orbicularis muscle, tarsus, and palpebral conjunctiva. The eyelid’s primary function is to protect the ocular surface, but they also function in cleansing and lubricating the eye. With each blink, the tear film is continuously spread over the ocular surface, maintaining optical visual clarity of the cornea. The subconscious blink reflex occurs every 6–10 seconds, and it has also been determined that significant restoration of the ocular surface occurs during extended times of closure, such as sleeping.

The conjunctiva is an ectodermally derived mucous membrane that extends from the mucocutaneous junction of the eyelid margins to the corneoscleral limbus.2 The conjunctival surface reflects onto the palpebral surfaces, creating fornices and folds, which allow for movement of the globe. Nasally, the plica semilunaris is formed by the folding of the conjunctiva. The conjunctival epithelium must be kept continuously moist to avoid desiccation.3 The conjunctival epithelium is rich in goblet cells, which are mucin-producing cells critical for the tear film. At the corneoscleral junction, the conjunctiva forms radial folds called the palisades of Vogt. The conjunctiva is also the sole source of lymphatic tissue of the eye, and therefore, has an important function in regard to protection against infection.

The final structure of the ocular surface is the cornea, which serves as the transparent window of the eye, allowing light rays to pass into the eye to be processed by the visual system. To accomplish this, the cornea must have a normal contour and be avascular, transparent, and be essentially dehydrated. The corneal epithelium is continuous with the conjunctival epithelium and both are composed of nonkeratinized, stratified, squamous epithelium cells. The corneal epithelium is 50 µm thick and has five or six layers of three different types of cells: superficial cells, wing cells, and basal cells. It is believed that the corneal epithelium is replaced by a population of stem cells found at the anatomical limbus.4 The corneal epithelium completely sheds and renews itself approximately every 7 days. The corneal epithelium is not a mucus membrane; however, it is susceptible to desiccation if not properly protected by the lids and tear film.

The lacrimal functional unit (LFU) has been described as an encompassing term representing the integrated system that comprises the ocular surface (cornea, conjunctiva, accessory lacrimal and meibomian glands), the main lacrimal glands, the blink mechanism that spreads tears, and the sensory and motor nerves that connect them whose parts act together and not in isolation.5 Poor function of this unit will often result in dry eye disease.

Eyelids and Eyelashes

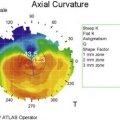

The critical relationship and dependence of the lid–lash complex to the ocular surface is described above. If the eyelid margin is not apposed to the corneal surface, significant ocular surface inflammation and mechanical trauma can occur. Flaws in the lid–lash complex, which can lead to instability of the ocular surface are myriad, but fall into two basic groups. One group leads to a mechanical rubbing and irritation of the ocular surface and the other is related to poor closure resulting in desiccation of the tissue. Disorders such as trichiasis, distichiasis, epiblepharon, lid imbrication syndrome, and entropion, cause ocular surface problems through the mechanical rubbing of lashes against the conjunctival and corneal surfaces. It is not only the trauma of the lashes rubbing, but also the induced chronic, low-grade inflammation, which further exacerbates the disease process. Most eyelid malpositions involve the lower lid. Trichiasis is distinguished from an entropion or epiblepharon by evaluating the lash orientation when the lid is in its normal position. Trichiasis refers to the condition where the lashes emerge from their normal anterior lamellar origin but are misdirected. Distichiasis is different from trichiasis in that the lashes originate from the more posterior meibomian gland orifices. Both conditions can be congenital or acquired. Another cause of mechanical trauma to the ocular surface creating significant inflammation is floppy eyelid syndrome. In this condition, the rubbery and floppy upper lid is everted during sleep and rubs on the pillow or sheets. This mechanical irritation creates a prominent papillary reaction on the upper palpebral conjunctiva, as well as punctate keratopathy on the cornea. Floppy eyelid is bilateral in 78% of patients, but can be asymmetric. Common external findings include a markedly elongated and lax upper lid and eyelash ptosis of the upper lid (Fig. 6.1). Patients often complain of ocular irritation, mucous discharge, and papillary conjunctivitis6 (Fig. 6.2). There are also reports of an association between keratoconus and floppy eyelid syndrome. One study reported 18% of their patients with floppy eyelid have clinical keratoconus and possibly up to 71% may have subclinical keratoconus.7

Other disorders such as lagophthalmos, eyelid retraction, and ectropion cause damage to the ocular surface by exposure. In these cases, incomplete closure of the lids allows for local increased tear film evaporation and subsequent corneal and conjunctival desiccation. Closure of the eyelids is primarily a function of the upper lid, with the lower lid exhibiting very little upward movement during closure. As a result, many patients tolerate lower lid retraction and scleral show with minimal symptoms, if the upper lid function is normal.8 Resultant inflammation will cause further insult to the ocular surface. Medical management to stabilize the ocular surface and reduce inflammation is important, but often the critical step is surgically addressing the abnormal lid position.

Lid Margin and Meibomian Glands

Blepharitis is a broad term used to describe inflammation of the lid as a whole. Anterior blepharitis is defined as inflammation of the lid margin anterior to the gray line and centered on the lashes. Marginal blepharitis refers to inflammation of the lid margin and includes both anterior and posterior blepharitis. Posterior blepharitis describes inflammation of the posterior lid margin, which may have different causes, including MGD, conjunctival inflammation, and acne rosacea.9 McCulley et al., in 1982, published six categories for blepharitis, with the first three describing anterior blepharitis and the final three posterior blepharitis and meibomian gland abnormalities. Anterior blepharitis is commonly associated with staphylococcal disease, as well as seborrhea, and presents with inflammation, crusting, and collarettes on the lashes.10

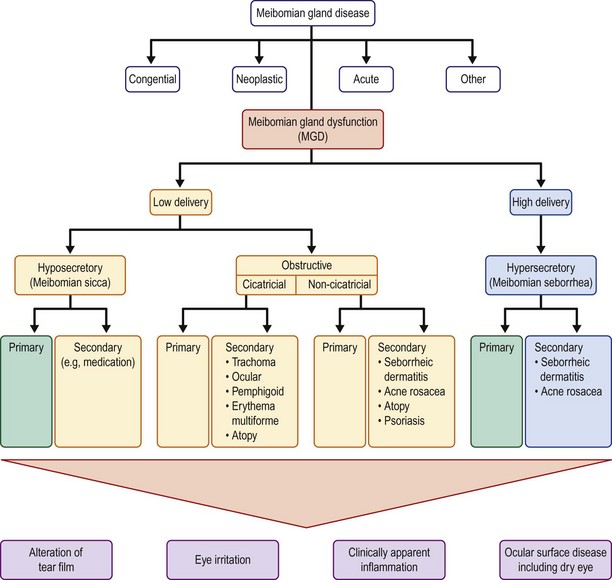

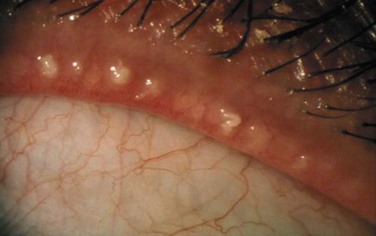

Hyposecretory MGD results from decreased meibum secretion without obvious obstruction. Hyposecretory MGD is seen clinically with gland atrophy and dropout. Contact lens wear has been associated with a decrease in the number of functional meibomian glands.9 Obstructive MGD is a result of obstruction of the duct, resulting in reduced delivery of meibum to the ocular surface. The gland orifice epithelium can become keratinized, creating a low-delivery state. Obstructive MGD is probably the most common form of MGD. Obstructive MGD is further divided into cicatricial and non-cicatricial. The cicatricial form of obstructive MGD results when the duct orifices are dragged posteriorly into the mucosa, as compared to non-cicatricial MGD where the ducts are obstructed but in their normal anatomic position. Causes of cicatricial obstructive MGD include trachoma, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, and atopic eye disease. Non-cicatricial obstructive MGD may be caused by Sjögren’s syndrome, seborrheic dermatitis, acne rosacea, atopy, and psoriasis9 (Fig. 6.3).

High-delivery, hypersecretory MGD is defined by the release of a large volume of lipid at the lid margin that is easily visible on examination with digital pressure on the glands. Seborrheic dermatitis has been reported to be associated with hypersecretory MGD in 100% of cases.9 Other causes include acne rosacea and atopic disease. In acne, increased sebum excretion on the face is a critical factor in the disease process9 (Fig. 6.4).

The prevalence of MGD reported in the ophthalmic literature varies widely from as low as 3.5%11 to almost 70%.12 One of the challenges of identifying a true prevalence is its wide range of symptoms and clinical findings, creating a broad spectrum that has significant overlap with other ocular surface disorders, specifically dry eye disease. One consistent finding has been the increased prevalence in the Asian population. Several studies12,13 have reported higher than 60% for the Asian population, compared to between 3.5%11 and 19.9%14 for Caucasians.

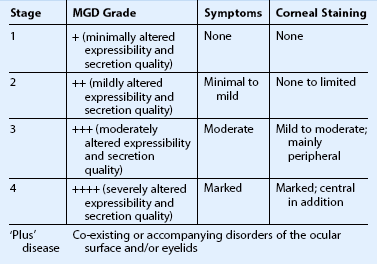

To better guide the clinician with treatment of MGD, the International Workshop devised a staging system for MGD. Four stages were defined based on expressability, secretion quality, symptoms, and corneal staining. Stage 1 refers to patients with minimally altered expressability and secretion quality, no symptoms, and no corneal staining. Stage 2 defines patients with mildly altered expressability and secretion quality, minimal to mild symptoms, and limited corneal staining. Stage 3 is defined as moderately altered expressability and secretion quality, moderate symptoms, and mild to moderate peripheral corneal staining. Stage 4 is defined as severely altered expressability and secretion quality, marked symptoms, and marked central corneal staining. Plus disease is reserved for patients with co-existing disorders of the ocular surface and/or eyelids15 (Table 6.1). The classification and staging of lid margin diseases will better aid the clinician, further our understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease process, improve our treatment options and patient outcomes, and guide future research studies in this field.

Tear Film and Dry Eye Syndrome

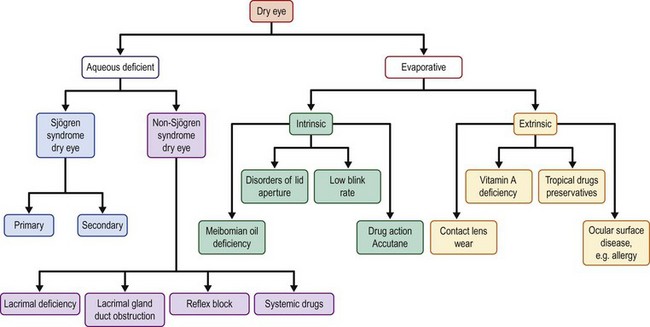

Dry eye disease (DED), or keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), is one of the most common conditions affecting patients worldwide. Abnormalities of the tear film are characterized by the component that is abnormal or deficient. Dry eye was defined by the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) as a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface.16 Historically, and from the DEWS report, DED is divided into two major subtypes: aqueous tear-deficient dry eye (ADDE) and evaporative dry eye (EDE) (Fig. 6.5).

Aqueous Tear-Deficient Dry Eye

Aqueous tear-deficient dry eye (ADDE) refers to dry eye that is due to failure of lacrimal secretion. The failure of lacrimal secretion due to lacrimal acinar destruction or dysfunction results in increased tear osmolarity and starts a cascade of inflammatory mediators to the ocular surface.16 ADDE is further subdivided into two groups: Sjögren’s syndrome dry eye (SSDE) and non-Sjögren’s syndrome dry eye. Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune process targeting the lacrimal and salivary glands. It is the second most common autoimmune rheumatologic disease, exceeded only by rheumatoid arthritis. There are two forms of SS: primary SS refers to cases where there is no other associated systemic connective tissue disease; secondary SS consists of the features of primary SS with the features of an overt autoimmune connective tissue disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematous, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, systemic sclerosis, primary biliary sclerosis, or mixed connective tissue disease. Diagnostic criteria including patient’s symptoms, ocular signs, salivary gland involvement, and presence of autoantibodies have been published to aid diagnosis17 (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2

Revised International Classification Criteria for Ocular Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome

I. Ocular symptoms: a positive response to at least one of the following questions:

1. Have you had daily, persistent, troublesome dry eyes for more than 3 months?

2. Do you have a recurrent sensation of sand or gravel in the eyes?

II. Oral symptoms: a positive response to at least one of the following questions:

1. Have you had a daily feeling of dry mouth for more than 3 months?

2. Have you had recurrently or persistently swollen salivary glands as an adult?

3. Do you frequently drink liquids to aid in swallowing dry food?

III. Ocular signs: that is, objective evidence of ocular involvement defined as a positive result for at least one of the following two tests:

1. Schirmer I test, performed without anesthesia (≤5 mm in 5 minutes)

2. Rose bengal score or other ocular dye score (≥4 according to van Bijsterveld’s scoring system)

IV. Histopathology: in minor salivary glands (obtained through normal-appearing mucosa) focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis, evaluated by an expert histopathologist, with a focus score ≥1, defined as a number of lymphocytic foci (which are adjacent to normal-appearing mucous acini and contain more than 50 lymphocytes) per 4 mm two of glandular tissue

V. Salivary gland involvement: objective evidence of salivary gland involvement defi ned by a positive result for at least one of the following diagnostic tests:

1. Unstimulated whole salivary flow (≤1.5 mL in 15 minutes)

2. Parotid sialography showing the presence of diffuse sialectasias (punctate, cavitary or destructive pattern), without evidence of obstruction in the major ducts

3. Salivary scintigraphy showing delayed uptake, reduced concentration and/or delayed excretion of tracer

VI. Autoantibodies: presence in the serum of the following autoantibodies:

(From Krachmer et al., Cornea, 3rd ed., Mosby, Elsevier 2010. Table 36.1.)

Non-SS dry eye is a form of ADDE due to lacrimal dysfunction, where the systemic autoimmune features characteristics of SSDE have been excluded. Age-related dry eye is the most common form; however, other forms include secondary lacrimal gland deficiencies, obstruction of the lacrimal gland ducts, and reflex hyposecretion.17 For age-related dry eye, alterations in ductal pathology with increasing age have been postulated as a cause of lacrimal gland dysfunction.18 Another contributing factor to age-related dry eye is the change in androgen levels with time, which is why postmenopausal women are one of the groups at highest risk of DED. Causes of secondary lacrimal gland deficiency include infiltration of the lacrimal gland in sarcoidosis, lymphoma, AIDS, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), lacrimal gland ablation, and lacrimal gland denervation.17 Cicatricizing conjunctivitis, caused by trachoma, pemphigoid, and erythema multiforme, and severe chemical and thermal burns can cause non-SS dry eye due to lacrimal gland duct obstruction. Finally, reflex hyposecretion can lead to non-SS dry eye due to reducing the reflex-induced lacrimal secretion and reducing the blink reflex leading to increasing evaporative loss. This reflex sensory block is common in diabetes mellitus and causes of neurotrophic keratitis, such as herpes simplex virus.17

Evaporative Dry Eye

Evaporative dry eye results from the exposed ocular surface losing water in the presence of normal lacrimal secretory function. Evaporative dry eye is further divided into intrinsic causes and extrinsic. Intrinsic causes include meibomian gland dysfunction, disorders of the lid aperture, and low blink rate. MGD, as discussed above, is the most common cause of evaporative dry eye. Proptosis due to thyroid eye disease, craniosynostosis, and orbital masses increase the area of exposure, resulting in worsening dry eye. Lagophthalmos, especially nocturnal, or incomplete closure after blepharoplasty are other causes of intrinsic evaporative dry eye. A reduced blink rate seen with focused near work or in Parkinson’s disease also causes evaporative dry eye.17

Extrinsic causes of evaporative dry eye include ocular surface disease, such as allergic conjunctivitis and vitamin A deficiency, contact lens wear, and preservatives in commonly used ophthalmic medicines. Many components of eye drop formulations can induce a toxic response from the ocular surface. Benzalkonium chloride, one of the most common offenders, causes surface epithelial cell damage and punctate epithelial keratitis, which interferes with surface wetability.17 Glaucoma patients treated for years with preservative-containing drops are at risk for evaporative dry eye. Contact lens use is extremely prevalent in the world today. The primary reasons for contact lens intolerance are dryness and discomfort.17 About 50% of contact lens wearers report dry eye symptoms.19 In addition, contact lens wearers are twelve times more likely than emmetropes to report dry eye symptoms and five times more likely than people wearing spectacles.20

Conjunctiva

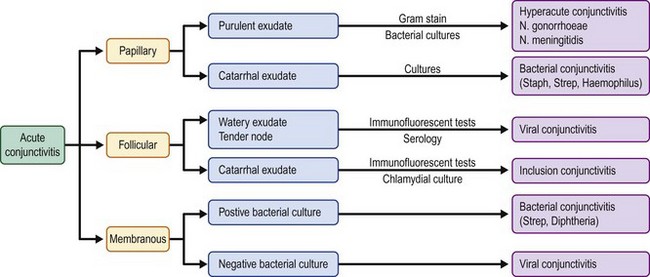

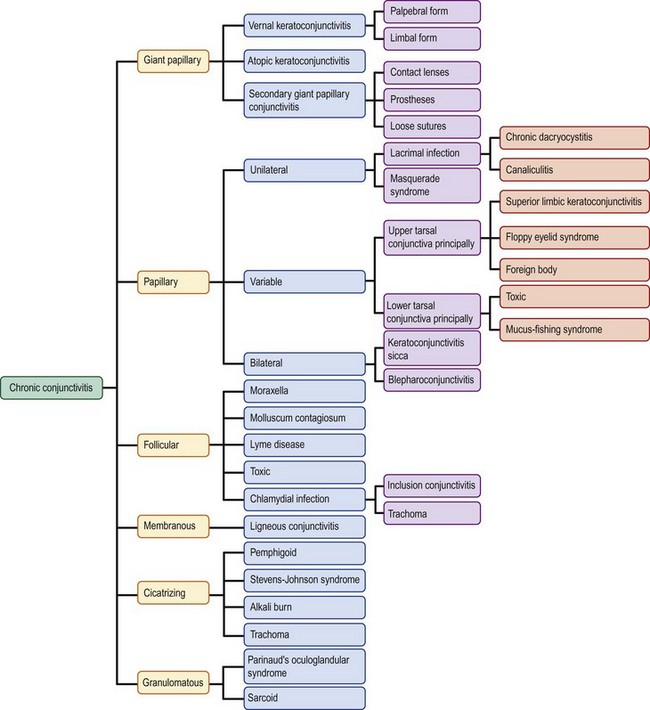

The hallmark of disorders of the conjunctiva is inflammation. The conjunctiva has a relatively simple histological structure that limits the response to inflammatory stimuli to five morphologic responses: papillary, follicular, membranous/pseudomembranous, cicatrizing, and granulomatous. Chronicity is also an important criterion for classification of conjunctivitis. Typically, acute conjunctivitis is defined as having a duration of less than 3 weeks.21 The most obvious sign of conjunctival inflammation is injection, which is typically accompanied by cellular infiltration and chemosis.21 Conjunctival exudates are often present and can aid the clinician in the diagnosis. The three types of exudates are purulent or hyperacute, mucopurulent or catarrhal, and watery. In addition, identification by the clinician of the most severely affected area of conjunctiva can aid the diagnosis (Fig. 6.6).

Non-specific inflammation may be accompanied by a papillary reaction of the tarsal conjunctiva. Causes of acute papillary conjunctivitis include primarily bacterial causes such as Neisseria species and Staphylococcus or Haemophilus. Chronic papillary changes can be seen in conditions such as superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, floppy eyelid, masquerade syndromes, mucus-fishing, dry eye disease, and dacryocystitis. If the papillae are greater than 1 mm in diameter they are considered giant papillae. These findings are typically seen in allergic disorders, such as vernal and atopic conjunctivitis, but can also be seen in relation to contact lens wear.21

Immune-mediated inflammation may show follicles of the tarsal or limbal conjunctiva. Follicles are yellowish, white, discrete, round, elevated lesions of the conjunctiva, that are more specific than papillary reactions. Acute follicular conjunctivitis is typically associated with viral etiologies, such as adenovirus and herpes simplex, but can also be found in inclusion conjunctivitis secondary to Chlamydia trachomatis. Chronic follicular conjunctivitis is most commonly due to Chlamydia, as either trachoma or inclusion conjunctivitis. Other causes of chronic follicular changes are Moraxella, molluscum contagiosum, and Lyme disease21 (Fig. 6.7).

Figure 6.7 Chronic follicular conjunctivitis.

In severe cases of conjunctivitis, fibrin membranes that are adherent to the conjunctival surface may develop. True membranes bleed when peeled, which differentiates them from pseudomembranes, and are more indicative of severe inflammation. Historically, bacterial infections from Corynebacterium and beta-hemolytic streptococci were the principal etiologies of acute membranous conjunctivitis; however, viruses such as adenovirus and herpes simplex are more common now.21 Ligneous conjunctivitis is the only chronic membranous conjunctivitis. Ligneous conjunctivitis is a rare form of conjunctivitis that presents with highly vascularized, friable, whitish membrane on the upper palpebral conjunctiva. Ligneous conjunctivitis has been associated with a plasminogen deficiency and can be treated with systemic and/or topical fresh frozen plasma.22

If the conjunctivitis involves only the epithelium and is short-lived, normal conjunctival anatomy and function will return once the inflammation has resolved.21 The end result of severe and chronic inflammation is irreversible changes, such as goblet cell damage and deficiency. Because goblet cells secrete mucin, which helps the aqueous tears coat the hydrophobic ocular surface, their loss will result in tear film abnormalities. Chronic conjunctival inflammation may lead to changes in the substantia propria of the conjunctiva, resulting in subepithelial fibrosis. With persistent inflammation, scar tissue can change the forniceal architecture and cause foreshortening of the fornix, hallmarks of cicatrizing conjunctivitis. Further progression of the chronic inflammatory process can lead to keratinization of the ocular surface, as well as symblepharon formation, and potentially even ankyloblepharon. Examples of cicatrizing conjunctivitis include Stevens–Johnson syndrome, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and chemical burns21 (Fig. 6.8).

The final morphologic response of the conjunctiva to inflammation is a granuloma. Sarcoid, retained foreign body, and Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome are often associated with conjunctival granulomas.21

Although a distinction exists between actively inflamed conjunctiva and that which is scarred but not inflamed, it must be understood that both situations represent abnormal conjunctiva. Actively inflamed conjunctiva is characterized by injection, chemosis, and the presence of immune mediators. Scarred, noninflamed conjunctiva is characterized by a decrease in mucin and aqueous tears, subepithelial fibrosis, and potentially foreshortening of the fornix and symblepharon. Both situations lead to an unhealthy ocular surface and create significant symptoms for patients.23

Corneal Epithelium

The final structure of the ocular surface is the cornea, which serves as the transparent window of the eye allowing light rays to pass into the eye to be processed by the visual system. To accomplish this, the cornea must have a normal contour and be avascular, transparent, and be essentially dehydrated. The corneal epithelium is continuous with the conjunctival epithelium and both are composed of nonkeratinized, stratified, squamous epithelium cells. It is believed that the corneal epithelium is replaced by a population of stem cells found at the anatomical limbus.4 The corneal epithelium is not a mucous membrane; however, it is susceptible to desiccation if not properly protected by the lids and tear film. As mentioned above, as a continuum of the ocular surface, most of the conditions mentioned in this chapter will have corneal manifestations.

Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency

Problems with the limbal stem cell population result in a decrease in the ability of the corneal epithelium to repopulate itself. Patients often complain of redness, irritation, photophobia, and decreased vision. On examination, early slit lamp findings include loss of the palisades of Vogt, late staining of the epithelium with fluorescein, corneal neovascularization, and development of peripheral pannus. Corneal findings often begin peripherally but may progress to involve the central cornea. Initially, the epithelium becomes irregular and hazy. Punctate epithelial keratopathy may develop, and these may coalesce to form true epithelial defects. Epithelial defects may be persistent, and may lead to stromal scarring, ulceration, and even perforation.23

Most cases of stem cell deficiency are acquired; however, congenital causes include aniridia, dominantly inherited keratitis, and ectodermal dysplasia. Acquired cases include chemical/thermal injury, contact lens use, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and rheumatoid arthritis.23

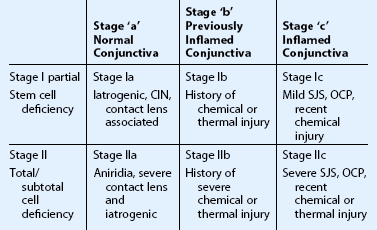

To aid the clinician and guide treatment approach, staging of severe ocular surface disease has been proposed.24 First, the patient is categorized based upon the extent of limbal stem cell depletion. Stage I defines patients with involvement of less than half of the limbus, stage II if greater than half of the limbus is deficient. The disease process and clinical findings for stage I are often mild compared to the persistent epithelial defects, vision-hampering conjunctivalization, and even stromal scarring, which occur more commonly with stage II disease. Next, the patient is categorized based upon the condition of the conjunctiva. If conjunctiva is normal, the patient is staged as ‘a.’ If the conjunctiva is abnormal from previous inflammation or injury but is currently quiet, the patient is staged as ‘b.’ If the conjunctiva is actively inflamed, the patient is staged as ‘c.’ Surgical management as well as prognosis are significantly affected based on the staging of these challenging patients.24

Examples of conditions that are classified as stage Ia include iatrogenic limbal stem cell deficiency, contact lens-induced keratopathy, and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Stage Ia disease can progress to IIa with further loss of limbal stem cells. Aniridia, a primary limbal stem cell disorder, is an entity that belongs in the IIa group, as the conjunctiva is often quiet. Patients with a prior history of chemical or thermal injury, with less than 50% limbal deficiency and quiet conjunctiva are labeled as stage Ib. Often, these patients have significant inflammation around the time of their injury (stage Ic or IIc), but the inflammation will quieten down over time, with judicious use of immunosuppressive agents. When planning surgery, it is best to wait for the inflammation to quieten down if possible, thus performing surgery when they are stage Ib rather than Ic. Other examples of stage Ic include conjunctival inflammatory disorders that have not reached the severe stage, such as mild SJS and OCP.25

Stage IIb is typically made up of patients with a history of chemical or thermal injury, affecting greater than half of the limbus. These patients are usually staged as IIc around the time of their exposure, and move to the IIb category when the conjunctiva becomes uninflamed. Total limbal stem cell deficiency with active conjunctival inflammation, represents the most severe cases of ocular surface disease. These cases make up stage IIc, and include severe SJS, OCP, and recent chemical injuries (Fig. 6.9). Clinical signs of stage IIc are conjunctival scarring, decreased mucin and aqueous tear production, and ocular surface keratinization. In this setting, stem cell transplantation is difficult due to the poor tear film, active inflammation, and abundance of immune mediators present. For these reasons, stage IIc patients have not only the worst natural disease course, but also the poorest prognosis for surgical rehabilitation25 (Table 6.3).

Figure 6.9 Stage IIc limbal stem cell deficiency.

References

1. Nerad, JA, Chang, A. Trichiasis. In: Chen WP, ed. Oculoplastic surgery: the essentials. New York: Thieme, 2001.

2. Nelson, J, Cameron, J, The conjunctiva. Cornea, 1st ed. Krachmer, JH, Mannis, MJ, Holland, EJ, eds. Cornea, Vol. 1. Mosby: St. Louis, 1997:41–47.

3. Tsubota, K, Tseng, SCG, Nordlund, ML. Anatomy and physiology of the ocular surface. In: Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, eds. Ocular surface disease: medical and surgical management. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002.

4. Cotsarelis, G, Cheng, S-Z, Dong, G, et al. Existence of slow-cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell. 1989;57:201–209.

5. Beuerman, RW, Mircheff, A, Plugfelder, SC, et al. The lacrimal functional unit. In: Plugfelder SC, Beuerman RW, Stern ME, eds. Dry eye and ocular surface disorders. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2004.

6. Schwartz, LK, Gelender, H, Forster, RK. Chronic conjunctivitis associated with floppy eyelids. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1884–1888.

7. Culbertson, WW, Tseng, SCG. Corneal disorders in floppy eyelid syndrome. Cornea. 1994;13:33–42.

8. Hall, AJ. Some observations on the active opening and closing of the eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1936;20:257–295.

9. Nelson, JD, Shimazaki, J, Benitez-del-Castillo, JM, et al. The International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. IOVS. 2011;52:1930–1937.

10. McCulley, JP, Dougherty, JM, Deneau, DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1173–1180.

11. Schein, OD, Munoz, B, Tielsch, JM, et al. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:723–728.

12. Jie, Y, Xu, L, Wu, YY, et al. Prevalence of dry eye among adult Chinese in the Beijing Eye Study. Eye. 2009;23:688–693.

13. Uchino, M, Dogru, M, Yagi, Y, et al. The features of dry eye disease in a Japanese elderly population. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83:797–802.

14. McCarty, CA, Bansal, AK, Livingston, PM, et al. The epidemiology of dry eye in Melbourne, Australia. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1114–1119.

15. Nichols, KK, Foulks, GN, Bron, AJ, et al. The International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: Executive Summary. IOVS. 2011;52:1922–1929.

16. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop (2007). Ocular Surf. 2007;5:75–92.

17. Vitali, C, Bombardieri, S, Johnson, R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;1:554–558.

18. Damato, BE, Allan, D, Murray, SB, et al. Senile atrophy of the human lacrimal gland: the contribution of chronic inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:674–686.

19. Doughty, MJ, Fonn, D, Richter, D, et al. A patient questionnaire approach to estimating the prevalence of dry eye symptoms in patients presenting to optometric practices across Canada. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:624–631.

20. Nichols, JJ, Ziegler, C, Mitchell, GL, et al. Self-reported dry eye disease across refractive modalities. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1911–1914.

21. Lindquist, TD. Conjunctivitis: an overview and classification. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2005:509–520.

22. Neff, KD, Holland, EJ, Schwartz, GS. Ligneous conjunctivitis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2005:629–634.

23. Schwartz, GS, Holland, EJ. Classification and staging of ocular surface disease. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2005:1713–1726.

24. Schwartz, GS, Gomes, JAP, Holland, EJ. Preoperative staging of disease severity. In: Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, eds. Ocular surface disease: medical and surgical management. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002.

25. Holland, EJ. Epithelial transplantation for the management of severe ocular surface disease. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1996;44:677–743.