CHAPTER 3 Classification

The classification of psychiatric disorders has been subject to changes over the decades. The two most well accepted and widely used current systems are the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD–10), and the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, revised (DSM–IVTR). These two classification systems differ in a number of important ways (see Table 3.1), but in terms of the psychiatric disorders they describe, there is rather more congruence than dissonance.

TABLE 3.1 Differences between DSM–IVTR and ICD–10

| DSM–IVTR | ICD–10 |

|---|---|

| US-based, published by the American Psychiatric Association, but has wide acceptance around the globe | Published by the World Health Organization; international perspective, and encompasses a diversity of opinion, including from a developing country perspective |

| Not part of a general medical classification system | Part of a general medical classification system |

| One version only | Clinical and research versions |

| Atheoretical | Groupings (‘blocks’) on the basis of presumed shared aetiologies |

| Multiaxial, with personality disorders on a separate axis (Axis II) | Personality disorders and intellectual disability (mental retardation) not on a separate axis |

| Global functioning assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale | Disability assessed using the Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO–DAS) |

One feature of both systems is that they provide operational criteria that rule diagnosis (ICD–10 applies operational criteria only in its research version). Operational criteria essentially provide a checklist of symptoms and signs, a proportion of which need to be endorsed for the subject to be considered a ‘case’; there are also usually some exclusionary items, such as a clear organic cause for the signs and symptoms. This approach has the downside of to some extent eschewing clinical intuition and judgment, and can lull one into a false sense of security regarding the validity of the constructs they describe. Indeed, none of the disorders in the nosologies are necessarily ‘true’ entities, and the boundaries of many are permeable. Also, there is a danger of labelling individuals according to their diagnosis, with all the associated downsides. Arguably, the psychiatric formulation is a much more satisfactory approach to understanding the individual and why they are presenting with certain symptoms at a specific time (see Ch 1).

The pragmatic classification system

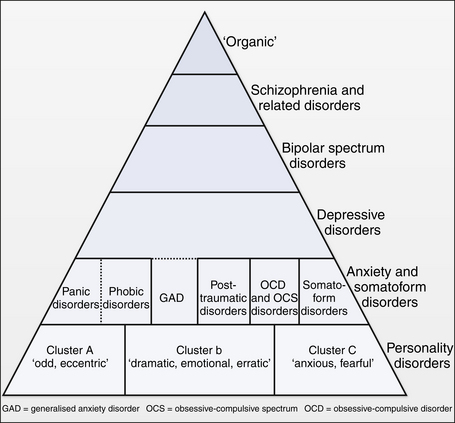

Figure 3.1 provides a schematic representation of the major psychiatric disorders in adults. A number of general issues should be noted:

It should also be noted that this schematic applies to adult psychopathology, and child and adolescent psychiatry adopts a somewhat different approach (see Ch 16). Finally, the schematic does not explicitly include the addictive disorders (see Ch 20), though they can be subsumed under the ‘organic’ rubric.

Organic disorders

In clinical practice, it is vital to examine each patient physically, and to perform laboratory tests where indicated (see Ch 2). One can consider organic factors as:

Causal. The factor is sufficient to cause the psychiatric symptoms (e.g. a temporal lobe tumour presenting as a post-ictal psychosis).

Causal. The factor is sufficient to cause the psychiatric symptoms (e.g. a temporal lobe tumour presenting as a post-ictal psychosis). Precipitating. For example, cannabis can precipitate a panic attack in vulnerable individuals, in part at least because of its propensity to induce tachycardia.

Precipitating. For example, cannabis can precipitate a panic attack in vulnerable individuals, in part at least because of its propensity to induce tachycardia.The organic disorders can themselves be classified, as shown in Box 3.1 (see Ch 4 for more details).

Schizophrenia and related disorders

Schizophrenia itself is at the core of this group. As discussed in Chapter 5, it is a disorder characterised by sets of symptoms in three main domains—namely, positive (delusions and hallucinations), negative (apathy, withdrawal, restriction of affect) and disorganisation (disorganised thoughts and actions; inappropriate affect). Cognitive impairment is also often part of the illness. DSM–IVTR requires a 6-month duration of symptoms (2 weeks of which should be ‘positive’ symptoms), while ICD–10 has an overall 1-month duration requirement.

For disorders characterised by features of schizophrenia (see Box 3.2), but of briefer duration, various terms are applied, including schizophreniform psychosis (DSM–IVTR), brief reactive psychosis (Scandinavia) and bouffee delirante (France).

On the border between schizophrenia and the affective disorders lies schizoaffective disorder, with an admixture of features of both sets of disorders. In DSM–IVTR, by definition, the features need to occur separately from each other, but other conceptualisations are less stringent and in clinical practice a schizoaffective label is often applied when patients have an admixture of mood and psychotic symptoms that do not lend themselves readily to either a schizophrenia or mood disorder label. This includes mood disorders with ‘mood incongruent’ delusions (i.e. the delusions are not explicable in terms of current mood state).

Bipolar spectrum disorders

Bipolar disorder was originally delineated along with unipolar mania, as distinct from unipolar depression. Nowadays, unipolar mania has been subsumed under the bipolar label. Thus, bipolar disorder, as detailed in Chapter 7, is characterised by episodes of mania (bipolar I) or hypomania (bipolar II): mania is a more severe form of hypomania, by definition requiring psychiatric treatment. More often than not sufferers also experience depressive episodes, which often are severe and prolonged, and carry significant morbidity and mortality (see Box 3.3).

Depressive disorders

No entirely satisfactory classification of the depressive disorders has yet been arrived at (see Box 3.4). For so-called major depressive disorder (MDD), DSM–IVTR stipulates a 2-week illness duration with features that must include pervasive low mood and/or loss of interest/pleasure. Dysthymia is a term reserved for those patients who have a chronic low-grade depression present on more days than not, for at least 2 years. Superimposed major depressive episodes in people with dysthymia is sometimes referred to as double depression.

Anxiety and somatoform disorders

The anxiety and somatoform disorders are divided here in a pragmatic manner, with a view to treatment implications (see Box 3.5). Further details can be found in Chapters 8, 9, 10 and 11.

BOX 3.5 Anxiety and somatoform disorders

Panic disorder is characterised by repeated panic attacks, at least half of which occur ‘out of the blue’. Once panics are linked to specific situations (e.g. crowds in agoraphobia, social situations in social phobia) or things (e.g. spiders or snakes in specific phobia), and there is consequent avoidance of those situations or things to an extent functioning is impaired, they can be considered phobic disorders. DSM–IVTR links panic with agoraphobia in particular, but panics can occur in any of the phobic disorders.

Post-traumatic syndromes in DSM–IVTR include an acute stress disorder (less than 1 month), and a more enduring (greater than 1 month) post-traumatic stress disorder. Symptoms are similar in each (see Box 3.6), but dissociation is given particular prominence in acute stress disorder. ICD–10 does not formally distinguish acute from more prolonged stress reactions.

The obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders are discussed in some detail in Chapter 9. Suffice to say here that there is a current vogue for grouping together a number of disorders into a so-called obsessive-compulsive spectrum (OCS), on the basis of shared symptomatology and treatment response. In fact, the veracity of the putative spectrum has been challenged, but for ease of discussion we can consider three main groupings, as shown in Figure 9.1. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) itself sits at the centre of this grouping. It is characterised by intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and associated compulsive acts aimed at reducing the anxiety associated with the thoughts. As outlined in Chapter 9, OCD is arguably itself a heterogeneous group of conditions, rather than an entity; certainly, hoarding does not sit easily under this label.

The somatoform disorders are a highly contentious and unsatisfactory grouping of disorders that ostensibly have somatisation at their core. They are discussed further in Chapter 11. DSM–IVTR includes body dysmorphic disorder here, but this approach has little to support it, and we have placed it in the OCD spectrum.

Personality disorders

The definition and classification of the personality disorders is particularly problematic. One reason for this is that the presence of another psychiatric disorder (an Axis I disorder in DSM–IVTR) can flavour the way the patient presents and lead to erroneous judgments being made about their personality. Also, personality disorders have often been seen as ‘untreatable’ (this is not in fact the case: see Ch 12) and the label often carries pejorative and unhelpful connotations. Furthermore, there is little empirical support for any of the proposed subtypologies, and much overlap between putative subtypes, such that patients more often than not fulfil criteria for a number of personality disorders at the same time. Finally, a number of personality disorders appear to be formes fruste of Axis I disorders: schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia are obvious examples (see Ch 5).

DSM–IVTR has taken a pragmatic approach to the problem. The establishment of a separate axis for personality disorders has its detractors, but has served to focus research attention on this group of maladies. A clustering of the personality disorders, as shown in Box 3.7, has little research validity, but can be of clinical utility.

References and further reading

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn, revised. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Berrios G.E. Classifications in psychiatry: a conceptual history. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:145-160.

Castle D.J., Jablensky A.V. Diagnosis and classification in psychiatry. In Wright P., Stern J., Phelan M., editors: Core psychiatry, 2nd edn, London: Saunders, 2005.

Cloninger C.R. A new conceptual paradigm from genetics and psychobiology for the science of mental health. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:174-186.

Foulds G.A. Hierarchical nature of personal illness. London: Academic Press; 1976.

Kendell R., Jablensky A. Distinguishing between validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:4-12.

Robins L., Guze S.B. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1970;126:983-987.

World Health Organization 1992 The ICD–10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization, Geneva