CHAPTER 7 Class IIA and B Ulnar Impaction: Treatment with Arthroscopic TFCC Disc Excision and Wafer Distal Ulna Resection

Introduction

The ulnar impaction syndrome refers to a painful overload of the ulnocarpal joint1,2 and has been classified by Palmar based on pathoanatomy (Table 7.1).3 Palmer and Werner have shown that positive ulnar variance results in an increase in ulnocarpal load,4 and this has been implicated in the etiology of degenerative triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears.4,25 Ulnar impaction also develops in the wrists with neutral or negative ulnar variance, however.5,6

Table 7.1 Classification of Traumatic and Degenerative Conditions of the TFCC

| Class I: Traumatic |

Dynamic increases in ulnar variance may occur with forearm pronation and grip,7,8,9 and an inverse relationship may exist between TFCC thickness and ulnar variance.10 Further, it is known that TFCC wear and undersurface fibrillation occur clinically prior to perforation11 and that innervation of the TFCC may in part explain pain early in the pathologic spectrum of this condition.12 Palmer’s classification of ulnar impaction accounts for the existence of TFCC wear without central disc perforation class IIA and B lesions.3 This chapter addresses the feasibility of arthroscopic TFCC disc excision and wafer distal ulna resection as treatment of ulnar impaction when TFCC perforation has not yet occurred. This procedure is a viable alternative to ulnar shortening osteotomy.

Biomechanics

Palmer and Werner have shown that in the ulnar neutral wrist 80% of the load is transferred across the radiocarpal joint compared to 20% across the ulnocarpal joint.4 When variance increases from neutral to 2.5 cm positive, however, ulnocarpal load increases by approximately 20%. Decreasing variance by 2.5 cm lowers force transmission from 20 to 5% in the neutral variant.

This data provides a basis for treating ulnar impaction syndrome with a shortening osteotomy of the ulna.1,2 Feldon advocated a wafer resection as an alternative in 1992,13 and in that same year Wnorowski et al. showed that an arthroscopic wafer procedure successfully diminished load across the ulnocarpal joint.14 Most recently, Markolf et al. have shown that wafer resection decreases distal ulna forces under all conditions of ulnar variance—although less effectively when variance exceeds 4 mm positive.15

Although Palmer and Werner have shown that increasing ulnar length results in an increase in force transmission across the distal ulna, and it is known that forearm pronation and forceful grip increase ulnar variance,5,16,17 few studies have investigated loads across the distal ulna when the forearm is pronated.10,18 In nine cadaver specimens in different wrist and forearm positions, Glisson et al. showed that loads across the distal ulna increased in pronation, wrist flexion, and ulnar deviation.18

Pfaeffle et al. evaluated the effect of axial load and forearm pronation on ulnar variance and distal ulna load in seven cadaver forearms.10 They found that ulnar variance increased an average of 2 mm in four ulnar positive and three ulnar neutral specimens. Distal ulna load increased in the ulnar neutral wrists and decreased in the ulnar positive wrists, in which greater dorsal subluxation of the distal radioulnar joint occurred. Accurate measurement of variance is important, therefore, when addressing ulnar wrist pain because the radioulnar length relationship has profound impact on load transfer across the wrist.19

Diagnosis

Nakamura’s ulnar stress test is routinely performed by ulnarly deviating the pronated wrist while axially loading, flexing, and extending.20 The “fovea test” is performed by asking the patient to flex the wrist. This allows palpation of the FCU, which facilitates locating the fovea of the TFCC between the FCU and ulnar styloid process. Positive ulnar stress and fovea tests, in combination, are roughly 98% sensitive in terms of correlation with an objective problem with the TFCC and/or LT ligament. Exclusion of other sources of discomfort—such as pisotriquetral arthritis, distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) instability or arthritis, and ECU tendonitis or hypermobility—increases the suspicion for pathology. An X-ray series is then obtained to evaluate ulnar variance and to assess for the presence of cystic changes in the ulnar corner of the lunate.

Imaging

Various methods of measuring ulnar variance have been described, but each uses neutral rotation posteroanterior (PA) radiographs of the wrist5,19,21 because pronation will slightly increase the length of the ulna. We routinely check a zero-rotation PA and a lateral view. In addition, a “pronated grip” radiograph is typically taken with the patient making a fist of maximum intensity while the forearm is in pronation.16 This X-ray may reveal positive ulnar variance not present on a neutral rotation X-ray because of dynamic changes in length when radial shortening occurs during forceful grip.16,17

Minami et al. were the first to report using a pronated-grip X-ray, and showed that positive ulnar variance was associated with poorer outcome following TFCC debridement alone.22 Their suggestion that persistent pain was related to positive ulnar variance is consistent with the message of two other reports that have shown the efficacy of ulnar shortening osteotomy in two situations: with TFCC repair to improve pain relief23 and to provide successful treatment of persistent ulnar wrist pain following TFCC debridement.7 Most recently, Minami and Kato have reported successful treatment of TFCC tears associated with positive ulnar variance using ulnar shortening osteotomy alone.24

The use of the pronated-grip X-ray attempts, therefore, to image the dynamic increase in ulnar variance—which may accompany forceful grip and pronation. Friedman et al. have reported that a maximum grip-effort grip resulted in an average increase in ulnar variance of 1.95 mm in asymptomatic volunteers.5 Tomaino showed an identical average increase in the measurement of ulnar variance in light of the fact that measurements in both reports were to the nearest 0.5 mm.17 Although these two studies do not prove that ulnar recession is required when variance becomes positive on the pronated-grip X-ray, pathomechanical and pathoanatomical data suggests that such positive variance may cause a problem.1,2,11

Indeed, high-resolution MR imaging has shown that the TFCC disc is thinner during forearm pronation.25 It is also known that the undersurface of the TFCC is innervated12 and undergoes degeneration prior to perforation.11 Although MR imaging may reveal marrow edema in the ulnar corner of the lunate, TFCC perforation, ulnar chondrosis, and a tear of the LT ligament,26,27 we no longer routinely order an MRI if the clinical suspicion is high for ulnar impaction and variance is positive on a pronated-grip X-ray.

Treatment

For degenerative TFCC tears, ulnar recession with either ulnar-shortening osteotomy or open wafer resection commonly provides satisfactory pain relief without the need for concomitant debridement of associated TFCC or LT tears. Indeed, even post-traumatic perforations of the TFCC have been treated with ulnar recession28 or by partial excision.29 For class IIA and B ulnar impaction pre-TFCC perforation lesions, ulnar shortening osteotomy1,2,30,31 is an option. However, our current preference is arthroscopic TFCC disc excision and wafer distal ulna resection.

Arthroscopic Wafer Procedure

Because TFCC debridement alone may not provide complete pain relief in wrists with positive ulnar variance—and in light of the efficacy of wafer distal ulna resection as a treatment for ulnar impaction syndrome,6,13,32,33 as well as the biomechanical effect of an arthroscopic wafer procedure in unloading the ulnocarpal joint14—Tomaino and Weiser evaluated the efficacy of an arthroscopic wafer procedure and TFCC debridement as a treatment for both post-traumatic and degenerative TFCC tears associated with positive ulnar variance.9

At final review, nine patients were very satisfied and three were satisfied. Among the former group, complete resolution of pain occurred in eight and one rated pain as minimal. Among the three patients who were only satisfied with the procedure, one had no pain but complained of portal sensitivity ulnarly, one complained of minimal pain referable to the SL joint, and one had minimal ulnar wrist pain during gripping activities.9 The ulnocarpal stress test failed to elicit pain in any patient, and the postoperative pronated-grip X-ray revealed that ulnar variance was neutral in all wrists.

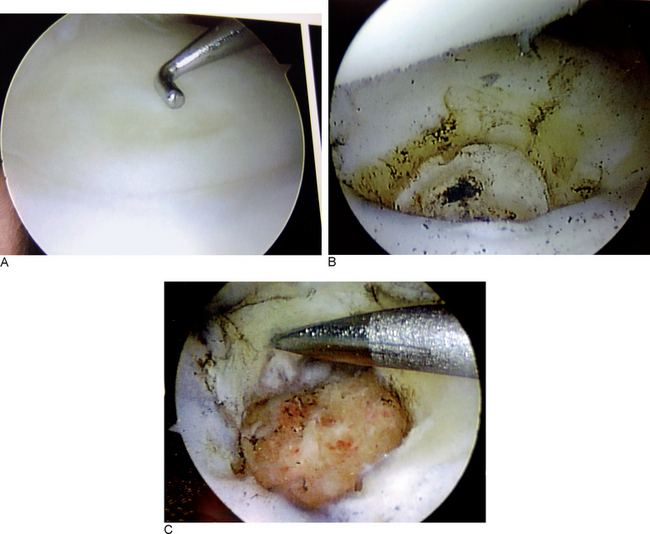

Our appreciation of class IIA and B lesions (TFCC wear and lunate chondrosis) at the time of the arthroscopic evaluation has allowed confirmation of the diagnosis of early stages of ulnar impaction (Figure 7.1). TFCC thinning and “pitting” are rather easily noted. Because of favorable results of arthroscopic wafer resection in the setting of TFCC perforation9—and the knowledge that isolated TFCC disc excision decreases ulnocarpal load and may address painful undersurface fibrillation11,12—we have been prospectively evaluating the results of arthroscopic TFCC disc excision and wafer resection for class IIA and B ulnar impaction for more than two years.

FIGURE 7.1 (A) Intraoperative picture shows TFCC wear. (B) After TFCC disc excision. (C) After wafer resection.

Inclusion criteria have included TFCC wear without perforation and positive ulnar variance on either the zero-rotation or pronated-grip X-ray. The volar and dorsal radioulnar ligaments and the attachment of the TFCC to the ulnar styloid are preserved. A wafer resection is then performed as described by Tomaino and Weiser (Figure 7.2).9 Our initial prospective evaluation has shown that 16 of 18 patients have experienced satisfactory pain relief at a minimum follow-up of one year. Having performed disc excision and wafer resection in more that 50 patients between 2002 and 2005, we have observed favorable results in 95% of cases.

Surgical Technique

A 2.9-mm bur is then brought in through the 6-R portal and a groove is made in the central portion of the ulnar head, proceeding volarly and dorsally as the wrist is pronated and supinated by an assistant. Initially a round bur is used, which is seated its full width to a depth of approximately 2.9 mm. Thereafter, subsequent planing may be achieved more easily—particularly when the bone is hard—using a conical 2.9-mm bur. After debris is removed with a shaver, it is critical to visualize the resected ulnar head completely to ensure that a full resection has been performed.

Summary

Although Palmer’s classification of TFCC lesions differentiates post-traumatic central perforations (1A tears) from degenerative tears secondary to ulnocarpal impaction (2C),3 the distinction is not always clear clinically. In the final analysis, the literature suggests that as many as 25% of wrists with TFCC tears have residual symptoms following arthroscopic debridement alone.22 It is also likely that either static or dynamic ulnar positive variance plays a role.2,5,17,24

Our observations suggest that combined arthroscopic TFCC debridement and wafer resection is feasible and provides efficacious treatment for all stages of ulnar impaction syndrome. When class IIA and B changes are observed (that is, when a TFCC perforation has not yet developed), we have observed favorable results in the majority of patients at one-year follow-up following arthroscopic TFCC central disc excision and wafer resection as an alternative to either ulnar shortening osteotomy31 or open wafer excision.6

1 Chun S, Palmer AK. The ulnar impaction syndrome: Follow-up of ulnar shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg. 1993;18A:46-53.

2 Friedman SL, Palmer AK. The ulnar impaction syndrome. Hand Clinics. 1991;7(2):295-320.

3 Palmer AK. Triangular fibrocartilage complex lesions: A classification. J Hand Surg. 1989;14A:594-606.

4 Palmer AK, Werner FW. Biomechanics of the distal radioulnar joint. Clin Orthop. 1984;187:26-35.

5 Friedman SL, Palmer AK, Short WH, Levinsohn EM, Halperin LS. The change in ulnar variance with grip. 1993;18A:713-716.

6 Tomaino MM. Results of the wafer procedure in ulnar impaction syndrome in the ulnar negative and neutral wrist. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1999;24B:671-675.

7 Hulsizer D, Weiss AC, Akelman E. Ulna-shortening osteotomy after failed arthroscopic debridement of the triangular fibrocartilage complex. J Hand Surg. 1997;22A:694-698.

8 Tomaino MM, Towers JD, Gainer M. Carpal impaction with the ulnar styloid process: Treatment with partial resection. J Hand Surg. 2001;26B:252-255.

9 Tomaino MM, Weiser RW. Combined arthroscopic TFCC debridement and wafer resection of the distal ulna in wrists with triangular fibrocartilage complex tears and positive ulnar variance. J Hand Surg. 2001;26A:1047-1052.

10 Pfaeffle HJ, Manson T, Fischer KJ, Herndon JH, Woo S L-Y, Tomaino MM. Axial loading alters ulnar variance and distal ulna load with forearm pronation. Pittsburgh Orthopaedic Journal. 1999;10:101-102.

11 Tomaino MM. Ulnar impaction syndrome in the ulnar negative and neutral wrist: Diagnosis and pathoanatomy. J Hand Surg. 1998;23B:754-757.

12 Ohmori M, Azuma H. Morphology and distribution of nerve endings in the human triangular fibrocartilage complex. J Hand Surg. 1998;23B:522-525.

13 Feldon P, Terrono AL, Belsky MR. Wafer distal ulna resection for triangular fibrocartilage tears and/or ulna impaction syndrome. J Hand Surg. 1992;17A:731-737.

14 Wnorowski DC, Palmer AK, Werner FW, Fortino MD. Anatomic and biomechanical analysis of the arthroscopic wafer procedure. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:204-212.

15 Markolf KL, Tejwani SG, Benhaim P. Effects of wafer resection and hemiresection from the distal ulna on load-sharing at the wrist: A cadaveric study. J Hand Surg. 2005;30A:351-358.

16 Tomaino MM, Rubin DA. The value of the pronated grip view radiograph in assessing dynamic ulnar positive variance: A case report. Am J of Ortho. 1999;3:180-181.

17 Tomaino MM. The importance of the pronated grip X-ray. J Hand Surg. 2000;25A:352-357.

18 Ekenstam FW, Palmer AK, Glisson RR. The load on the radius and ulna in different positions of the wrist and forearm: A cadaver study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55(3):363-365.

19 Palmer AK, Glisson RR, Werner FW. Ulnar variance determination. J Hand Surg. 1982;7:376-379.

20 Nakamura R, Horii E, Imaeda T, Nakao E, Kato H, Watanabe K. The ulnocarpal stress test in the diagnosis of ulnar-sided wrist pain. J Hand Surg. 1997;22B:719-723.

21 Steyers CM, Blair WF. Measuring ulnar variance: A comparison of techniques. J Hand Surg. 1989;14A:607-612.

22 Minami A, Ishikawa J, Suenage N, Kasashima T. Clinical results of treatment of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears by arthroscopic debridement. J Hand Surg. 1996;21A:406-411.

23 Trumble TE, Gilbert M, Vedder N. Ulnar shortening combined with arthroscopic repairs in the delayed management of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. J Hand Surg. 1997;22A:807-813.

24 Minami K, Kato H. Ulnar shortening for triangular fibrocartilage complex tears associated with ulnar positive variance. J Hand Surg. 1998;23A:904-908.

25 Nakamura T, Yabe Y, Horiuchi Y. Dynamic changes in the shape of the triangular fibrocartilage complex during rotation demonstrated with high resolution magnetic resonance imaging. J Hand Surg. 1999;24B:338-341.

26 Escobedo EM, Bergman G, Hunter JC. MR imaging of ulnar impaction. Skeletal Radiology. 1993;24:85-90.

27 Imaeda T, Nakamura R, Shionoya K, Makino N. Ulnar impaction syndrome: MR imaging findings. Radiology. 1996;201:495-500.

28 Boulas JH, Milek MA. Ulnar shortening for tears of the triangular fibrocartilagenous complex. J Hand Surg. 1990;15A:415-420.

29 Menon J, Wood VE, Schoene HR. Isolated tears of the triangular fibrocartilage of the wrist: Results of partial excision. J Hand Surg. 1984;9A:527-530.

30 Loh YC, Van Den Abbeele K, Stanley JK, Trail IA. The results of ulnar shortening for ulnar impaction syndrome. J Hand Surg. 1999;24B:316-320.

31 Tatebe M, Nakamura R, Horii E, Nakao E. Results of ulnar shortening osteotomy for ulnocarpal impaction syndrome in wrists with neutral or negative ulnar variance. J Hand Surg. 2005;30B:129-132.

32 Schuurman AH, Bos KE. The ulno-carpal abutment syndrome. J Hand Surg. 1995;20B:171-177.

33 Tomaino MM, Shah M. Treatment of ulnar impaction syndrome with the wafer procedure. Am J Ortho. 2001;30:129-133.