CHAPTER 28 Circumvertical Breast Reduction and Mastopexy

Key Points

Summary

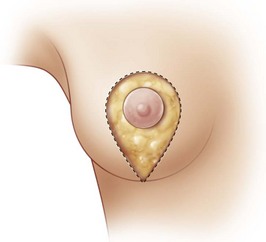

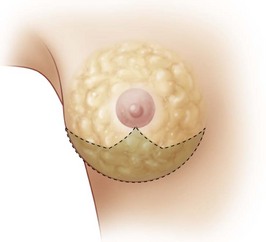

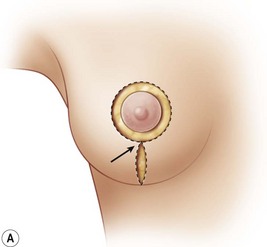

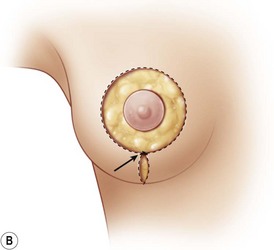

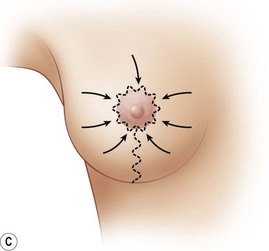

The concept of the circumvertical technique on the skin is to prolong the periareolar technique and shorten the vertical component (Fig. 28.1). At the end of the procedure, the excess skin is distributed in two directions – around the areola and in the vertical component. The skin is adjusted to create an even distribution of wrinkles in both the areola and vertically. The vertical scar does not cross the inframammary fold.

After the vertical reduction from Lassus1,2 and Lejour3,4 other techniques have evolved1,5–7 such as the vertical with the medial pedicle, published by Hall-Findlay8 and the circumvertical one published in 1997, which will be described now.

In breast reductions, the differences between the circumvertical and the other vertical techniques lie not only regarding the way the skin is redistributed during the final suture, but also for more profound reasons. These are the W-pattern parenchyma removal (Fig. 28.2), the different ways to build a round-conic projected breast and the absence of a pedicle for the areola transposition. At the end of the surgery the following are observed: a well-shaped breast, with a harmonic distribution of the wrinkles around the areola and the vertical scar never crossing the inframammary fold (IMF).

Operative Technique

Markings

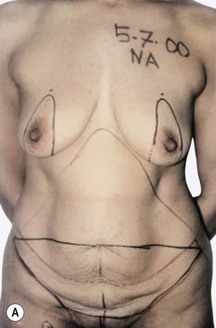

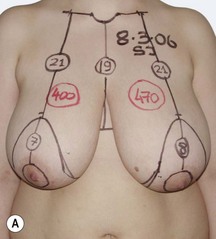

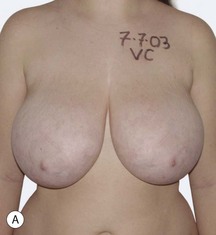

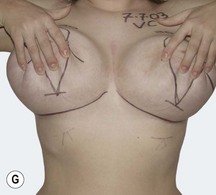

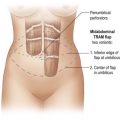

Breast reductions

First, the IMF is marked. The vertical lines passing through the nipple go to the external notch if the areola is to be moved superomedially but they go to the midclavicular line if the areola is only to be moved superiorly. Then the areola is moved into position so that all of the final areolar projection will be above the future submammary fold. The superior border of the areola is then marked on the vertical meridian line. According to the amount of periareolar skin resection needed, 5–6 cm on each side of the nipple are marked, but this could be 4–7 cm if a lateralized areola is to move medially. Then, from the superior mark, a semicircumference is marked and from there two vertical lines are dropped downwards, which converge 2–4 cm above the IMF. The same markings are made on the contralateral side with appropriate adjustments if the breast is larger, smaller, or more ptotic (Fig. 28.3).

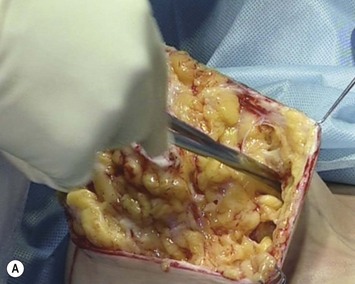

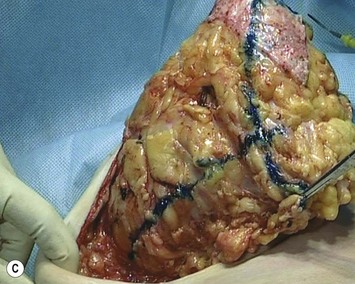

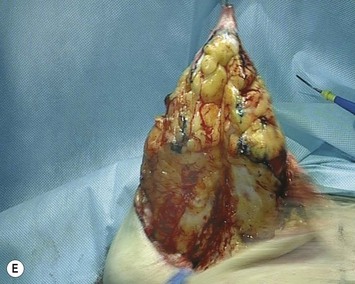

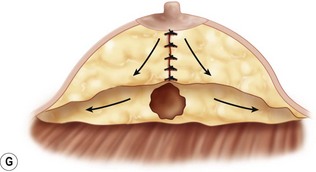

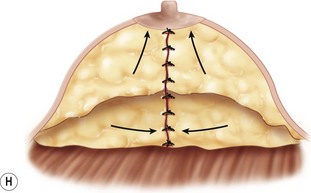

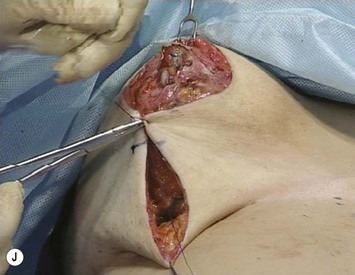

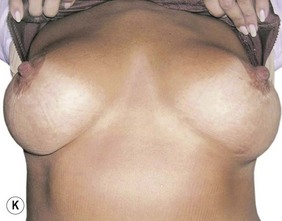

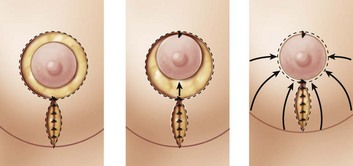

Once the whole periareolar skin is de-epithelialized, the skin is undermined at the inferior half of the breast both medially and laterally leaving 1 cm thick subcutaneous tissue to preserve its blood supply (Fig. 28.4A). The inferior half of the breast is also detached from the pectoralis major muscle up to the fourth intercostal space, where the perforator of the fourth intercostal nerve usually emerges (Fig. 28.4B). This way, the dissected breast emerges and holding up the breast with a hook, a Wise pattern resection is marked, which is at the inferior quadrant and at the inferior part of the medial and lateral quadrants (Fig. 28.4C–E). After the resection, the lateral and medial glandular edges are sutured medially in two to three layers using a 3-0 Vicryl suture. If the breast is to project more centrally, both pillars can be imbricated (Fig. 28.4F, G). To have a more projected breast, two to three stitches are placed at the base of the cone in order to keep the pillars together (Fig. 28.4H, I). Once a conic-shaped breast has been obtained, the inferior edge of the parenchyma is fixed to the pectoralis fascia where it now sits using five to seven 3-0 Vicryl separate stitches placed all along what will be the future IMF. At this time, some defatting can be done to give a more even round breast shape. Then the areola is moved to the superior border of the skin and fixed with two to three subdermal 3-0 Vicryl sutures. To finish the surgery, a stitch is placed at 8–10 cm from the inferior part of the skin angle, thus dividing the wound into two parts: the superior round periareolar and the inferior vertical ellipse (Fig. 28.4J). The areola is moved upwards and sutured to the superior skin edge (Fig. 28.4K). The inferior wound is sutured in a vertical fashion with a 3-0 Vicryl subdermal running suture. The periareolar skin is sutured to the areolar border with another a subdermal cinching running suture. This running suture takes big 10–12 mm horizontal bites at the skin dermis and 2–3 mm vertical bites at the areola dermis. This way, after three passes the thread is pulled tight and the skin gathers toward the areola. The suturing is continued all around the areola to give an even distribution of wrinkles all along the areola border and to ensure no dead spaces are left. To finish the surgery, all the wounds are closed with intradermal 5-0 Vicryl suture. Aspiration drains are placed laterally and adhesive tape fixes the wounds. Figures 28.4L, M show the final result. Figure 28.5 shows a representative example.

Results

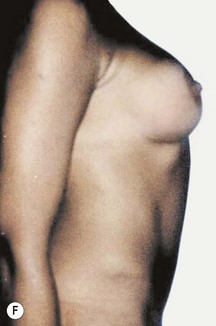

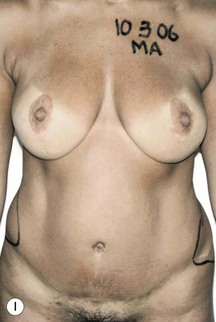

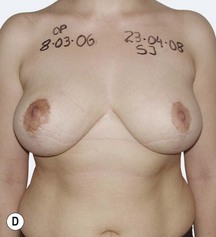

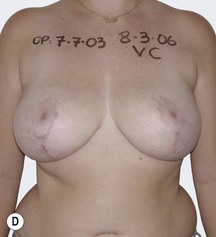

I started using the circumvertical technique for breast reduction in 1992 so I have experience in over 300 breast reductions (Figs 28.6 and 28.7). Periareolar techniques are used, however, when prospective reductions are around 200 g. Between 200 and 1000 g, the circumvertical technique is used, but over 1000 g I prefer the inverted T. I have used the circumvertical technique removing more than 1200 g but even when the scars are vertical, the results are suboptimal. The ideal breast is a round firm breast, with minor ptosis and, the less ideal is a flat hanging breast with poor skin quality.

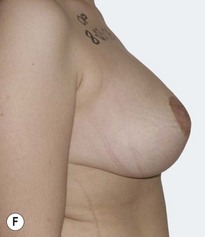

Thirty years ago when the idea of the purse-string suture did not even exist, I started using a primitive circumvertical technique described by Arie,9 in minor or moderate breast ptosis. I first began using the purse-string suture10 and then changed it for cinching sutures11 and then changed to the cinching running suture. I have used the cinching suture in 60 mastopexy patients. The indication for this technique is for cases in which the breast volume is good and a flat breast shape needs to be corrected and the breast lifted. It is a good technique with only very few minor complications (Fig. 28.8).

Discussion

Breast markings and technique

The markings are followed and the estimation of the amount of glandular removal is planned before surgery. This is especially important when there is asymmetry. As there is a great variety of breast hypertrophy, I also plan before surgery from which part of the breast I have to remove more tissue. When there are difficult asymmetries I usually draw a draft of the future areas to be removed as a surgical guide. I do not use liposuction to reduce the volume because I can better reshape a firm conic breast with scalpel and sutures. Suturing the breast pillars vertically and at the base of the breast, I can project a flat breast (Fig. 28.4H, I). The new conic shape of the breast is sculpted in this way. By suturing the new inferior border of the breast to the pectoralis fascia, a clear IMF is defined and the gland is fixed to the muscle, thus avoiding the possible bottoming out of the breast.

When the inferior part of the breast is removed, the skin that previously covered the breast, will now attach to the thoracic wall. The suture that divided the wound can be adjusted during surgery. If it is placed in a higher position, the periareolar diameter will be reduced and the vertical will be enlarged while if it is placed in a lower position, the periareolar diameter will be wider and the vertical one will be shortened (Fig. 28.9A, B). The possibility of such variations is important when I have to determine an even distribution of the wrinkles.

The subdermal running periareolar cinching suture approximates the skin to the areola leaving no dead spaces. As the wrinkles are evenly distributed at the periareolar and vertical incisions, and the undermined skin retracts during surgery, an acceptable, good result can be observed when the surgery is finished (Fig. 28.9C).

Once the areola is moved and fixed to the superior border of the skin, all the skin moves toward the areola. The superior part of the vertical wound is also sutured to the 6 oclock areolar dermis; the vertical wound ascends and does not cross the IMF (Fig. 28.10). To avoid long scars,12 as I do in a good proportion of cases, I have never had to transform a vertical into an inverted T during or after surgery.

Pitfalls and How to Correct

1 Lassus C. Breast reduction: evolution of a technique: a single vertical scar. Aesth Plast Surg. 1987;11:107-112.

2 Lassus C. Update on vertical mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:7.

3 Lejour M. Suction mammaplasty. Correspondence. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:1.

4 Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty and liposuction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:1.

5 Graf R. In search of better shape in mastopexy and reduction mammoplasty. Plast Reconst Surg. 2002;110:309.

6 Graf R. Breast shape: a technique for better upper pole fullness. Aesth Plast Surg. 2000;24:348.

7 Menke H, Restel B, Olbrisch RR. Vertical scar reduction mammaplasty as a standard procedure – experiences in the introduction and validation of a modified reduction technique. Eur J Plast Surg. 1999;22:74-79.

8 Hall-Findlay E. A simplified vertical reduction mammaplasty: shortening the learning curve. Plast Reconst Surg. 1999;104:748.

9 Arie G. Una nueva técnica de mastoplástia. Rev Latinoam Cir Plast. 1957;3:23-28.

10 Benelli L. A new periareolar mammaplasty: the ‘round block’ technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 1990;14:93-100.

11 Ersek RA, Ersek SL. Circular cinching stitch, ideas and innovations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:2.

Hammond D. The SPAIR mammaplasty. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2002. p. 411

Mottura AA. Local anesthesia in reduction mastoplasty for out-patient surgery. Aesth Plast Surg. 1992;16:309-315.

Mottura AA. Mastoplastia reductiva con anestesia local. Rev Arg de Mastol. 1990;9:56.

Mottura AA, Procikieviez O. Mastoplastia reductiva periareolar. Rev Arg de Cir Plast. 1996;2:195-198.

Mottura AA. Zirkumverticale mammareduktionplastik. In: Lemperle G, editor. Aesthetische chirurghie. 1st edn. Ecomed, Grand Werk; 1998:1-5.

Mottura AA. Circumvertical reduction mastoplasty. Aesth Surg J. 2000;20:199-204.