Circumcision

Circumcision (removal of the redundant prepuce) is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures in the world. There is a wide variability in the rate of circumcision among different populations. A lack of consensus regarding the function of the foreskin and uncertainty regarding the benefits of circumcision has led to controversy regarding the appropriateness of elective circumcision. The most recent policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states ‘the health benefits of newborn male circumcision outweigh the risks and the procedure’s benefits justify access to this procedure for those families who choose it’.1

Circumcision has been practiced since ancient times. A common reason for elective circumcision centers on religious beliefs. The Bible declares circumcision to be the sign of the covenant between God and the people of Israel.2 In the Muslim faith, circumcision is recommended, but not obligatory.3 Circumcision is common in the USA, areas of Africa, Australian aborigines, and portions of the Middle East.4,5 In contrast, routine circumcision is rarely performed in Europe, Asia, and Central and South America.4 This variation in incidence likely reflects religious and cultural differences.

The Prepuce

The prepuce is the anatomical covering of the glans. Contributing to the debate concerning the appropriateness of routine circumcision is a poor understanding of its function. The prepuce is specialized junctional mucocutaneous tissue that has both somatosensory and autonomic innervation. Innervation of the prepuce differs from the glans, which is innervated by free nerve endings with protopathic sensitivity. As a result of these differences, the inner mucosa of the prepuce is felt to be a part of penile erogenous tissue.6 Given the possible relationship between the prepuce and sexual satisfaction, studies have looked into outcomes following circumcision.

Problems with sexual dysfunction (inability to ejaculate, lacking interest, premature ejaculation, pain during sex, not enjoying sex) appear to be slightly more prevalent among uncircumcised men.7 For sexually active adult males undergoing circumcision, there does not appear to be any adverse, clinically important effects on sexual function or satisfaction.8–11 Other studies, however, have shown difficulty with sexual enjoyment, erectile function, and a decrease in masturbatory pleasure following circumcision.11,12 These mixed results hold true for homosexual men as well.13 The effects on female partners of adult males who are circumcised are similarly mixed. Some report dyspareunia, orgasm difficulties, and incomplete needs fulfillment, while others report no significant problems at all.14,15

Medical Indications

The inability to retract the foreskin of a newborn is the result of incomplete keratinization of the glans and is not pathologic. Phimosis is the inability to retract the foreskin. True phimosis is associated with a white, scarred preputial orifice, most common just before puberty, and is an indication for circumcision.16 Balanitis xerotica obliterans is a ring-like distal sclerosis of the prepuce with whitish discoloration or plaque formation that may involve the prepuce, glans, or urethral meatus, and is also an indication for circumcision.17 Paraphimosis occurs when the foreskin has been retracted behind the corona and is unable to be brought back over the glans. This is also an indication for circumcision, though ardent opponents of circumcision would offer preputial stretching, plasty, or topical steroid creams as alternative therapy.18–21 Balanitis is an infection of the glans, and posthitis is an infection of the prepuce. Recurrent infection with scarring of the prepuce is also an indication for circumcision.5,22

Routine Circumcision at Birth

The appropriateness of routine circumcision of healthy newborn males is an emotional and contentious issue. Underlying the argument is a poor understanding as to the function of the prepuce.23 Opponents have presented circumcision as a symbol of the ‘therapeutic state’,24 a mutilating procedure,25 and have questioned the ethics and legality of newborn circumcision, especially with respect to human rights considerations and the notion of respect for bodily integrity.26,27 Opponents have also cited an association between circumcision and subsequently developing poor breastfeeding outcomes, delayed cognitive abilities, and neonatal jaundice. However, these concerns have not been substantiated.28,29 One urologic study among children without urinary complaints did find a relationship between circumcision and meatal stenosis.30

Circumcision is performed on the eighth day in the Jewish faith, traditionally by a mohel, a member of the faith trained in circumcision. In Islamic countries, circumcision is considered traditional but not obligatory, with a wide variability in age at circumcision.3,31

Proponents for routine newborn circumcision generally cite three advantages: prevention of urinary tract infections,32 prevention of sexually transmitted disease, and prevention of cancer, both penile and prostate.

As rates of circumcision have diminished in the USA, reports have appeared showing an increased rate of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in uncircumcised infants with a male predominance in infants younger than 3 months of age.33 A disproportionate number were uncircumcised. A large retrospective analysis of infants from military families suggested that uncircumcised infants have a 12-fold increased risk for UTI compared with circumcised infants.34–36 A prospective study found a reduced incidence of asymptomatic UTI in circumcised children.37 Finally, there is a tenfold increase in the cost of managing UTIs in uncircumcised compared to circumcised infants.38

An increased incidence of infection in uncircumcised children is believed to be secondary to adherence of pathogenic bacteria to the prepuce and may also hold true for young adults.39,40 Proponents point to the 10% incidence of concurrent bacteremias and long-term sequelae of renal scarring after infection.41 Critics have countered that these studies are retrospective analyses and that other studies associate genitourinary infection with circumcised children.42–44 Additionally, they argue that colonization of the prepuce by nonmaternal uropathic bacteria could be prevented by strict rooming-in with the mother.45

There are many studies examining the relationship between circumcision and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).46 The benefits of circumcision relative to STDs are a strong factor in the support of circumcision in the new AAP statement. Studies have shown that uncircumcised individuals have an increased risk of acquiring Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human papillomavirus (HPV), and genital herpes.47–50 However, other studies have found little support for or have refuted these findings altogether.7,51,52 There is also evidence that circumcision is associated with a decreased risk of cervical cancer in women.48 It is possible that the protective effect of circumcision against STDs may differ between developed and developing nations with poor hygiene.51 Possible mechanisms for differing rates of STDs in relation to circumcision status include a more easily traumatized mucosa and epithelium of the uncircumcised phallus, the foreskin environment being more conducive to pathogens, or nonspecific balanitis in uncircumcised men predisposing to certain STDs. Behavior and sexual practice still represent the greatest risk factors in STD transmission.48

Epidemiological studies of HIV and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) have raised another argument for prophylactic circumcision. There is a substantial amount of evidence linking uncircumcised men with an increased risk of HIV infection that is independent of the increased risk of genital ulcers in uncircumcised men.53 In Africa, there is an increased rate of HIV/AIDS observed in areas with low circumcision rates.54 A meta-analysis from Africa concluded that there was enough evidence that circumcision was associated with reduced HIV infection rates to consider male circumcision as a strategy to reduce HIV transmission.45 Three randomized trials in Africa showed an estimated 50–60% reduction in the relative risk of HIV infection with circumcision.54,55 Similar findings have been noted in the USA, with uncircumcised homosexual men having a twofold increase in the risk of HIV infection.56,57 An uncircumcised male partner also appears to be associated with an increased risk of transmission of HIV to heterosexual contacts.58 The most recent Cochrane reviews cite a protective association between circumcision and HIV acquisition, and recommend routine circumcision among heterosexual men while stopping short of recommending the same in homosexual men.59,60

Circumcision may act as a protective measure against cancer, both prostate and invasive penile. It is believed that these cancers have infectious etiologies and that rationale underlies the reasoning that circumcision before first sexual intercourse may be associated with a decreased risk of prostate cancer.61 The uncircumcised state has been strongly associated with invasive penile cancer in multiple case series, especially given its strong association with HPV.53,62 The incidence of penile cancer in the USA is approximately one case per 100,000, with nearly all cases occurring in uncircumcised men.63,64 The protective effect against penile cancer is diminished or lost when circumcision is performed after the newborn period.5,64,65 Other factors associated with invasive penile cancer include smoking, a history of genital warts, penile rash or tears, multiple sexual partners, and poor penile hygiene.53,65 Critics cite equally low rates of penile cancer in developed countries with low circumcision rates and feel that the incidence of penile cancer does not justify routine neonatal circumcision.43,62

There is no definitive answer to the question of the appropriateness of routine newborn circumcision. Current studies do not provide conclusive evidence definitively for or against routine newborn circumcision. Males not circumcised at birth have between a 2–10% likelihood of needing circumcision.21,25 A longitudinal study comparing circumcised with uncircumcised males showed a higher risk of penile ‘problems’ in infancy in the circumcised group.66 However, there was a higher rate of ‘problems’ in the uncircumcised group after infancy. By 8 years, the uncircumcised group had experienced 50% more penile ‘problems.’

The previous circumcision policy statement from the AAP in 1999 acknowledged the potential medical benefits of newborn male circumcision, but did not recommend routine neonatal circumcision.53 The 2012 statement states that the preventive health benefits outweigh the risks of the procedure, recommending access to the procedure but stopping short of recommending routine circumcision.1 In the USA, the parental decision for newborn circumcision seems to be based more on social than medical reasons.67

Surgical Technique

Circumcision has been practiced for centuries. Common to all methods, the goal is removal of an adequate amount of prepuce to uncover the glans, treat or prevent phimosis, and eliminate the possibility of paraphimosis. Whichever method is chosen, the surgeon must be familiar with and adept at the technique with a resultant low complication rate.1 Informed consent should always be obtained.68

Newborn Circumcision

Circumcision is the most frequently performed male operation in the USA, with 64% of newborn males infants circumcised in 1995.53 Newborn circumcision is most frequently performed with a device, which may be a shield, used in traditional Jewish circumcision, a Mogen clamp, a Gomco clamp, or a Plastibell.4 Prior to the procedure, the penis should be inspected for any contraindication to circumcision including a short or small phallus, hypospadias, chordee with no hypospadias, hooded prepuce, dorsal penile cutaneous hump, penile curvature or torsion, penoscrotal fusion, or large inguinal hernias or hydroceles that engulf the penis.69

There is agreement for the need for adequate analgesia as studies have shown infants circumcised without analgesia have a stronger pain response to vaccination at 4 and 6 months of age as compared to those receiving analgesics.70 Another study, looking at pain in relation to timing, recommended circumcision before 8 days of age.71 Effective relief of circumcision pain has been found with acetaminophen, topical lidocaine–procaine cream, and local nerve blocks.72–75 One study showed a subcutaneous ring block with 1% lidocaine without epinephrine to be the most effective pain relief.53 Sucrose on a pacifier can also provide added pain control.76

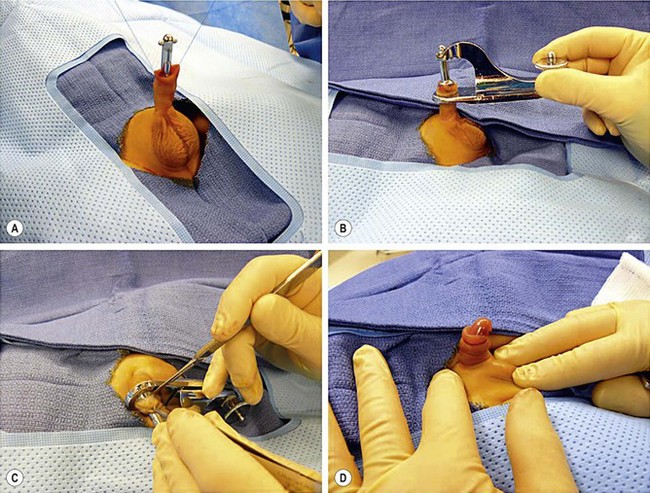

Even though many circumcisions are performed outside the operating room, antisepsis is critical as infection is a serious potential complication. In performing a Gomco circumcision, the field is sterilely prepped, and adhesions between the glans and inner surface of the prepuce are bluntly separated. The extent of foreskin to be excised is marked with a pen or a crush of the dorsal prepuce with a straight clamp. A dorsal slit allows the appropriate-sized bell to be placed over the glans, inside the prepuce (Fig. 60-1). The bell and foreskin are then brought through the opening in the clamp, placed in the yoke, and then tightened. The excess foreskin distal to the base of the clamp is then excised after waiting for several minutes. Electrocautery should never be used because of transmission of the electrical current to the penis. The bell is released and removed, taking care not to disrupt the weld between the shaft skin and the remnant of the inner surface of the prepuce.

FIGURE 60-1 The Gomco technique. (A) A short dorsal slit has been performed to allow an appropriate-sized bell to be placed over the glans and inside the prepuce. (B) Next, the prepuce to be excised along with the bell have been brought through the opening in the base of the clamp and placed in the yoke. (C) The yoke has then been tightened to coapt the skin edges. After waiting for 5 to 7 minutes, the excess prepuce is excised. Electrocautery must never be used to excise the foreskin because transmission of electrical current to the shaft of the penis will occur. (D) The bell has been released, and the circumcision is completed.

A Plastibell allows strangulation of the distal foreskin, with a resulting slough of the tissue. After sterile prep and dorsal slit, the appropriate-sized Plastibell is placed over the glans inside the prepuce (Fig. 60-2). A string is then tied around the prepuce, and positioned over a groove in the bell. The excess foreskin is trimmed and the handle is broken off the bell. The distal foreskin remnant and ring typically slough off in seven to 14 days.

FIGURE 60-2 Similar to the Gomco technique, in the Plastibell technique, adhesions between the glans and inner surface of the prepuce are bluntly separated. (A) An appropriate-size Plastibell has been selected. (B) The Plastibell is placed over the glans inside the prepuce. (C) A string is then tied around the prepuce and positioned in the groove of the bell. The excess foreskin is trimmed and the handle is broken off the bell. The foreskin remnant and bell are expected to slough in one to two weeks.

Revision Circumcision

Following recovery from any of the above procedures, there may be redundancy or asymmetry of residual preputial skin that may not meet the cosmetic expectations of the family.77 In situations where the family feels the redundant, residual prepuce is unsightly, or with a postoperative phimosis, they may seek an opinion regarding revision. As with primary circumcision, there is controversy surrounding the medical necessity and ethics of revision.78

One study reported 46 revisions where the indications were primarily preputial redundancy, residual cicatrix, preputial-glandular bridges, a sebaceous cyst and urethrocutaneous fistula.79 Two other reported studies of circumcision revision both reported using the freehand or sleeve technique, with the most common indication being residual or redundant preputial skin.79–81

Freehand Circumcision

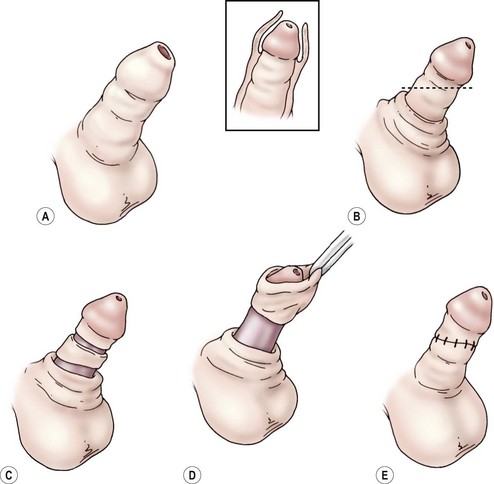

In older patients, circumcision is usually performed in the operating room and devices are less often used. As stated above, in cases of circumcision revision, the freehand technique is the preferred method. As shown in Figure 60-3, after prepping the field, any remaining adhesions between the glans and foreskin are bluntly lysed.

FIGURE 60-3 (A) For a freehand circumcision, the initial incision is made in the shaft skin, leaving more skin ventrally. (B) A second incision is then made in the subcoronal sulcus (C), leaving a generous cuff. The inset shows the amount of foreskin to be excised. (D) The isolated foreskin is then excised, and the shaft skin is sutured to the subcoronal skin (E).

After marking the subcoronal sulcus, the foreskin is incised along the base of the glans with the foreskin in its normal position. Less skin is excised from the ventral surface. Dissection is carried down to Buck’s fascia. The prepuce is then retracted and an incision made in the subcoronal sulcus, leaving a generous cuff of subcoronal skin. Injury to the urethra must be avoided ventrally. The collar of foreskin that is isolated is excised and electrocautery is used to obtain hemostasis. The shaft skin is approximated to the subcoronal skin using absorbable sutures.

Complications

When performed by experienced hands under sterile conditions, circumcision has a low complication rate between 2–10%.62 Bleeding and infection are the most frequent complications and are generally minor.1 Although adhesions between the foreskin remnant and the glans are common, most will resolve with time.82 However, serious problems can result, including necrotizing fasciitis, sepsis, Fournier’s gangrene, and meningitis.5 Other complications include skin bridges, inclusion cysts, iatrogenic hypospadias or epispadias, partial glans amputation, and catastrophic loss of the penis when electrocautery is used with a metal device. There can be excision of too much or too little of the foreskin, with resultant postoperative phimosis or concealed penis. As described above, revision may sometimes be necessary later in childhood.81

References

1. Circumcision Policy. Statement. Pediatrics. 2012; 130:585–586.

2. The Holy Bible. King James ed.

3. Rizvi, SA, Naqvi, SA, Hussain, M, et al. Religious circumcision: A Muslim view. BJU Int. 1999; 83(Suppl. 1):13–16.

4. Holman, JR, Lewis, EL, Ringler, RL. Neonatal circumcision techniques. Am Fam Physician. 1995; 52:511–518.

5. Niku, SD, Stock, JA, Kaplan, GW. Neonatal circumcision. Urol Clin North Am. 1995; 22:57–65.

6. Cold, CJ, Taylor, JR. The prepuce. BJU Int. 1999; 83(Suppl. 1):34–44.

7. Laumann, EO, Masi, CM, Zuckerman, EW. Circumcision in the United States. Prevalence, prophylactic effects, and sexual practice. JAMA. 1997; 277:1052–1057.

8. Collins, S, Upshaw, J, Rutchik, S, et al. Effects of circumcision on male sexual function: Debunking a myth? J Urol. 2002; 167:2111–2112.

9. Senkul, T, Iser, IC, Sen, B, et al. Circumcision in adults: Effect on sexual function. Urology. 2004; 63:155–158.

10. Kigozi, G, Watya, S, Polis, CB, et al. The effect of male circumcision on sexual satisfaction and function, results from a randomized trial of male circumcision for human immunodeficiency virus prevention, Rakai, Uganda. BJU Int. 2008; 101:65–70.

11. Fink, KS, Carson, CC, DeVellis, RF. Adult circumcision outcomes study: Effect on erectile function, penile sensitivity, sexual activity and satisfaction. J Urol. 2002; 167:2113–2116.

12. Kim, D, Pang, MG. The effect of male circumcision on sexuality. BJU Int. 2007; 99:619–622.

13. Mao, L, Templeton, DJ, Crawford, J, et al. Does circumcision make a difference to the sexual experience of gay men? Findings from the Health in Men (HIM) cohort. J Sex Med. 2008; 5:2557–2561.

14. Kigozi, G, Lukabwe, I, Kagaayi, J, et al. Sexual satisfaction of women partners of circumcised men in a randomized trial of male circumcision in Rakai, Uganda. BJU Int. 2009; 104:1698–1701.

15. Frisch, M, Lindholm, M, Gronbaek, M. Male circumcision and sexual function in men and women: A survey-based, cross-sectional study in Denmark. Int J Epidemiol. 2011; 40:1367–1381.

16. Rickwood, AM. Medical indications for circumcision. BJU Int. 1999; 83(Suppl. 1):45–51.

17. Gargollo, PC, Kozakewich, HP, Bauer, SB, et al. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in boys. J Urol. 2005; 174(4 Pt 1):1409–1412.

18. Cooper, GG, Thomson, GJ, Raine, PA. Therapeutic retraction of the foreskin in childhood. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983; 286(6360):186–187.

19. Cuckow, PM, Rix, G, Mouriquand, PD. Preputial plasty: A good alternative to circumcision. J Pediatr Surg. 1994; 29:561–563.

20. Holmlund, DE. Dorsal incision of the prepuce and skin closure with Dexon in patients with phimosis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1973; 7:97–99.

21. Lerman, SE, Liao, JC. Neonatal circumcision. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001; 48:1539–1557.

22. Escala, JM, Rickwood, AM. Balanitis. Br J Urol. 1989; 63:196–197.

23. Taylor, JR, Lockwood, AP, Taylor, AJ. The prepuce: Specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision. Br J Urol. 1996; 77:291–295.

24. Szasz, T. Routine neonatal circumcision: Symbol of the birth of the therapeutic state. J Med Philos. 1996; 21:137–148.

25. Weiss, GN, Weiss, EB. A perspective on controversies over neonatal circumcision. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994; 33:726–730.

26. Van Howe, RS, Svoboda, JS, Dwyer, JG, et al. Involuntary circumcision: The legal issues. BJU Int. 1999; 83(Suppl. 1):63–73.

27. Dekkers, W. Routine (non-religious) neonatal circumcision and bodily integrity: A transatlantic dialogue. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2009; 19:125–146.

28. Fergusson, DM, Boden, JM, Horwood, LJ. Neonatal circumcision: Effects on breastfeeding and outcomes associated with breastfeeding. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008; 44:44–49.

29. Eroglu, E, Balci, S, Ozkan, H, et al. Does circumcision increase neonatal jaundice? Acta Paediatr. 2008; 97:1192–1193.

30. Joudi, M, Fathi, M, Hiradfar, M. Incidence of asymptomatic meatal stenosis in children following neonatal circumcision. J Pediatr Urol. 2011; 7:526–528.

31. Sari, N, Buyukunal, SN, Zulfikar, B. Circumcision ceremonies at the Ottoman palace. J Pediatr Surg. 1996; 31:920–924.

32. Mendez-Gallart, R, Estevez, E, Bautista, A, et al. Bipolar scissors circumcision is a safe, fast, and bloodless procedure in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2009; 44:2048–2053.

33. Ginsburg, CM, McCracken, GH, Jr. Urinary tract infections in young infants. Pediatrics. 1982; 69:409–412.

34. Wiswell, TE, Enzenauer, RW, Holton, ME, et al. Declining frequency of circumcision: Implications for changes in the absolute incidence and male to female sex ratio of urinary tract infections in early infancy. Pediatrics. 1987; 79:338–342.

35. Wiswell, TE, Geschke, DW. Risks from circumcision during the first month of life compared with those for uncircumcised boys. Pediatrics. 1989; 83:1011–1015.

36. Wiswell, TE, Hachey, WE. Urinary tract infections and the uncircumcised state: An update. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1993; 32:130–134.

37. Simforoosh, N, Tabibi, A, Khalili, SA, et al. Neonatal circumcision reduces the incidence of asymptomatic urinary tract infection: A large prospective study with long-term follow up using Plastibell. J Pediatr Urol. 8, 2012.

38. Schoen, EJ, Colby, CJ, Ray, GT. Newborn circumcision decreases incidence and costs of urinary tract infections during the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2000; 105(4 Pt 1):789–793.

39. Roberts, JA. Norwich-Eaton lectureship. Pathogenesis of nonobstructive urinary tract infections in children. J Urol. 1990; 144(2 Pt 2):475–480.

40. Spach, DH, Stapleton, AE, Stamm, WE. Lack of circumcision increases the risk of urinary tract infection in young men. JAMA. 1992; 267:679–681.

41. Wiswell, TE. The prepuce, urinary tract infections, and the consequences. Pediatrics. 2000; 105(4 Pt 1):860–862.

42. American Academy of Pediatrics. Report of the Task Force on Circumcision. Pediatrics. 1989; 84:388–391.

43. Poland, RL. The question of routine neonatal circumcision. N Engl J Med. 1990; 322:1312–1315.

44. Prais, D, Shoov-Furman, R, Amir, J. Is ritual circumcision a risk factor for neonatal urinary tract infections? Arch Dis Child. 2009; 94:191–194.

45. Winberg, J, Bollgren, I, Gothefors, L, et al. The prepuce: A mistake of nature? Lancet. 1989; 1(8638):598–599.

46. Tobian, AA, Serwadda, D, Quinn, TC, et al. Male circumcision for the prevention of HSV-2 and HPV infections and syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:1298–1309.

47. Castellsague, X, Bosch, FX, Munoz, N, et al. Male circumcision, penile human papillomavirus infection, and cervical cancer in female partners. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1105–1112.

48. Cook, LS, Koutsky, LA, Holmes, KK. Circumcision and sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Public Health. 1994; 84:197–201.

49. Parker, SW, Stewart, AJ, Wren, MN, et al. Circumcision and sexually transmissible disease. Med J Aust. 1983; 2:288–290.

50. Tobian, AA, Gray, RH, Quinn, TC. Male circumcision for the prevention of acquisition and transmission of sexually transmitted infections: The case for neonatal circumcision. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010; 164:78–84.

51. Donovan, B, Bassett, I, Bodsworth, NJ. Male circumcision and common sexually transmissible diseases in a developed nation setting. Genitourin Med. 1994; 70:317–320.

52. Dickson, NP, van Roode, T, Herbison, P, et al. Circumcision and risk of sexually transmitted infections in a birth cohort. J Pediatr. 2008; 152:383–387.

53. Circumcision policy statement. American Academy of Pediatrics. Task Force on Circumcision. Pediatrics. 1999; 103:686–693.

54. Moses, S, Plummer, FA, Bradley, JE, et al. The association between lack of male circumcision and risk for HIV infection: A review of the epidemiological data. Sex Transm Dis. 1994; 21:201–210.

55. Vardi, Y, Sadeghi-Nejad, H, Pollack, S, et al. Male circumcision and HIV prevention. J Sex Med. 2007; 4(4 Pt 1):838–843.

56. Kreiss, JK, Hopkins, SG. The association between circumcision status and human immunodeficiency virus infection among homosexual men. J Infect Dis. 1993; 168:1404–1408.

57. Xu, X, Patel, DA, Dalton, VK, et al. Can routine neonatal circumcision help prevent human immunodeficiency virus transmission in the United States? Am J Mens Health. 2009; 3:79–84.

58. McCarthy, KH, Studd, JW, Johnson, MA. Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. Br J Hosp Med. 1992; 48:404–409.

59. Siegfried, N, Muller, M, Deeks, JJ, et al. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009.

60. Wiysonge, CS, Kongnyuy, EJ, Shey, M, et al. Male circumcision for prevention of homosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011.

61. Wright, JL, Lin, DW, Stanford, JL. Circumcision and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer. 2012; 118:4437–4443.

62. Neonatal circumcision revisited. Fetus and Newborn Committee, Canadian Paediatric Society. CMAJ. 1996; 154:769–780.

63. Schoen, EJ, Fischell, AA. Dorsal penile nerve block for circumcision. JAMA. 1989; 261:701–702.

64. Schoen, EJ. The relationship between circumcision and cancer of the penis. CA Cancer J Clin. 1991; 41:306–309.

65. Maden, C, Sherman, KJ, Beckmann, AM, et al. History of circumcision, medical conditions, and sexual activity and risk of penile cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993; 85:19–24.

66. Fergusson, DM, Lawton, JM, Shannon, FT. Neonatal circumcision and penile problems: An 8-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 1988; 81:537–541.

67. Brown, MS, Brown, CA. Circumcision decision: Prominence of social concerns. Pediatrics. 1987; 80:215–219.

68. Christakis, DA, Harvey, E, Zerr, DM, et al. A trade-off analysis of routine newborn circumcision. Pediatrics. 2000; 105(1 Pt 3):246–249.

69. Redman, JF, Elser, JM. Neonatal circumcision: Anatomic contraindications. J Ark Med Soc. 1997; 94:73–75.

70. Taddio, A, Katz, J, Ilersich, AL, et al. Effect of neonatal circumcision on pain response during subsequent routine vaccination. Lancet. 1997; 349(9052):599–603.

71. Banieghbal, B. Optimal time for neonatal circumcision: An observation-based study. J Pediatr Urol. 2009; 5:359–362.

72. Howard, CR, Howard, FM, Weitzman, ML. Acetaminophen analgesia in neonatal circumcision: The effect on pain. Pediatrics. 1994; 93:641–646.

73. Lenhart, JG, Lenhart, NM, Reid, A, et al. Local anesthesia for circumcision: Which technique is most effective? J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997; 10:13–19.

74. Serour, F, Cohen, A, Mandelberg, A, et al. Dorsal penile nerve block in children undergoing circumcision in a day-care surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1996; 43:954–958.

75. Taddio, A, Stevens, B, Craig, K, et al. Efficacy and safety of lidocaine-prilocaine cream for pain during circumcision. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336:1197–1201.

76. Herschel, M, Khoshnood, B, Ellman, C, et al. Neonatal circumcision. Randomized trial of a sucrose pacifier for pain control. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998; 152:279–284.

77. Kaplan, GW. Complications of circumcision. Urol Clin North Am. 1983; 10:543–549.

78. Fleiss, PM. Re: Circumcision revision in prepubertal boys: Analysis of a 2-year experience and description of a technique. J Urol. 1995; 154:1143–1144.

79. Redman, JF. Circumcision revision in prepubertal boys: Analysis of a 2-year experience and description of a technique. J Urol. 1995; 153:180–182.

80. Al-Ghazo, MA, Banihani, KE. Circumcision revision in male children. Int Braz J Urol. 2006; 32:454–458.

81. Brisson, PA, Patel, HI, Feins, NR. Revision of circumcision in children: Report of 56 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2002; 37:1343–1346.

82. Ponsky, LE, Ross, JH, Knipper, N, et al. Penile adhesions after neonatal circumcision. J Urol. 2000; 164:495–496.