Circulatory System

Recognize and use terms related to the anatomy and physiology of the circulatory system.

Recognize and use terms related to the anatomy and physiology of the circulatory system.

Recognize and use terms related to the pathology of the circulatory system.

Recognize and use terms related to the pathology of the circulatory system.

Recognize and use terms related to the procedures for the circulatory system.

Recognize and use terms related to the procedures for the circulatory system.

ICD-10-CM Example from Tabular

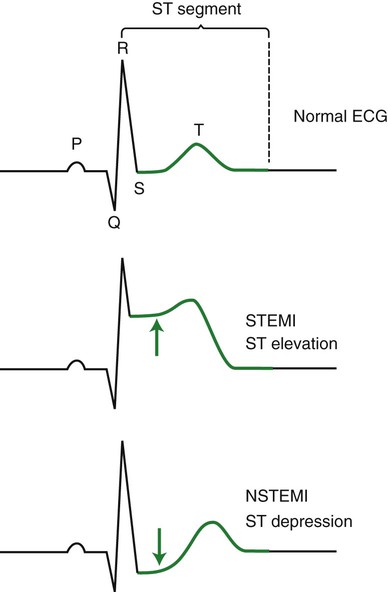

I21.0 ST elevation (STEMI) myocardial infarction of anterior wall

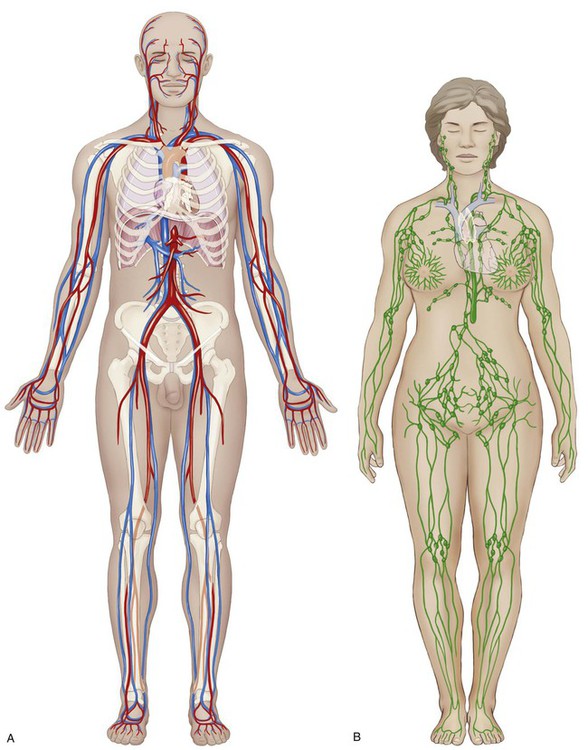

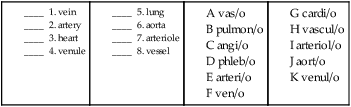

The circulatory system includes the body systems of the heart and vessels (the cardiovascular system) as well as that of the lymphatic organs, nodes, and their own specialized vessels (the lymphatic system) (Fig. 9-1). These subdivisions of the character for body systems comprise over a quarter of the specific body systems detailed in the Medical and Surgical section of the PCS, so as you may expect, there is a great deal of anatomy to be covered. Your knowledge of medical terminology word parts will make it much easier.

• circulatory system functions

• pulmonary and systemic circulation

• blood flow through the heart

The Cardiovascular System

Functions of the Cardiovascular System

The primary function of the circulatory system (Fig. 9-1) is to provide a means of transportation for nutrients, water, oxygen, hormones, and body salts (to) and wastes (from) the cells of the body. It also serves a protective role by dispatching specialized defensive cells through the lymphatic system. Both of these tasks require anatomical structures and mechanisms that direct these “highways” to every cell of the body without stopping. As will be discussed, any disruption to these functions may result in a disease or disorder of the circulatory system.

Pulmonary and Systemic Circulation

Pulmonary Circulation

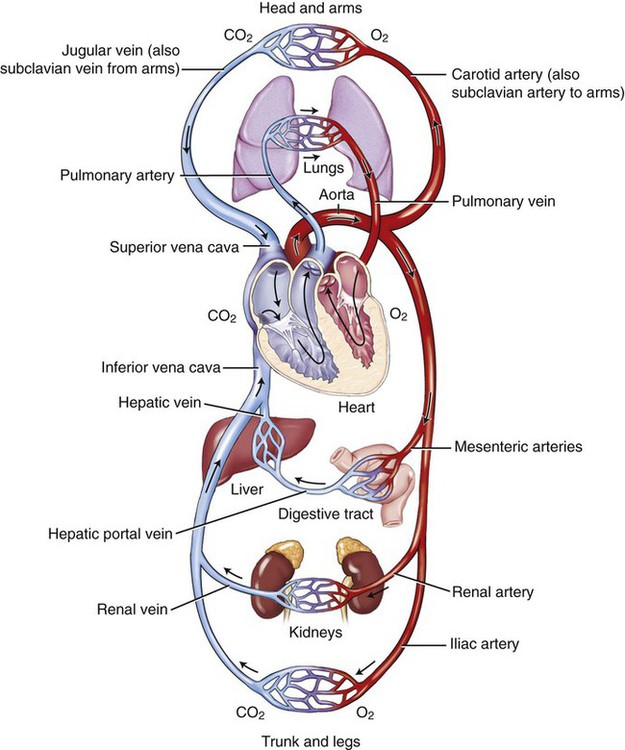

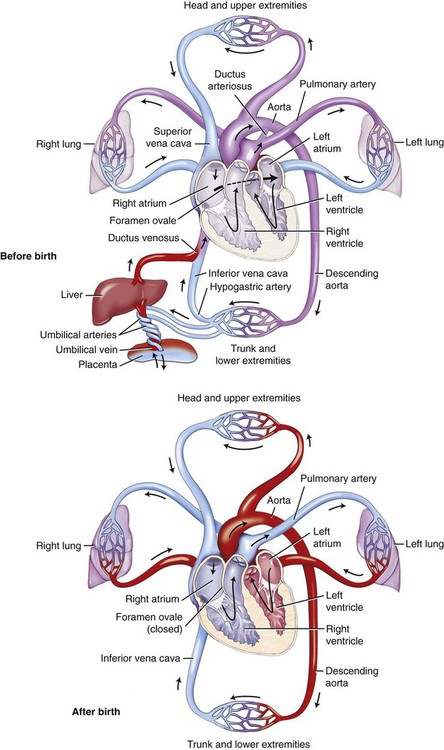

Pulmonary circulation begins with the right side of the heart, sending blood to the lungs to absorb oxygen (O2) and to release carbon dioxide (CO2). Note in Figure 9-2 that the vessels that carry blood to the lungs from the heart are blue—to show the blood as being deoxygenated, or oxygen deficient. Once the oxygen is absorbed, the blood is considered oxygenated, or oxygen rich. Note also in Figure 9-2 that the vessels traveling away from the lungs are red—to show oxygenation. The blood then progresses back to the left side of the heart, where it is pumped out to begin its route through the systemic circulatory system.

Systemic Circulation

Systemic circulation carries blood from the heart to the cells of the body, where nutrient and waste exchange takes place. Certain organs of the body are key to the process of waste removal. During systemic circulation, blood passes through the kidneys. This part of systemic circulation is known as renal circulation. In this phase, the kidneys filter much of the waste from the blood to be excreted in the urine. Blood also passes through the small intestine during systemic circulation. This phase is known as portal circulation. Here, the blood from the small intestine collects in the portal vein, which passes through the liver. The liver filters sugars from the blood and stores them for use as needed. On return to the right side of the heart, the blood is pushed out to the lungs to dispose of its CO2, absorb O2, and repeat the cycle. Figure 9-2 shows the oxygenated/deoxygenated status of blood.

In systemic circulation, the blood traveling away from the heart first passes through the largest artery in the body called the aorta. From the aorta, the vessels branch into conducting arteries, then into smaller arterioles, and finally to the capillaries. Note in Figure 9-2 that the color has changed from the red of oxygenated blood to a purple color at the capillaries. This is the site of exchange between the cells’ fluids and the plasma of the circulatory system. Oxygen and other substances are supplied, and carbon dioxide is collected, along with a number of other wastes. Once the blood begins its journey back to the heart, it first goes through venules, then veins, and finally into one of the two largest veins, the superior or inferior vena cava. The great vessels include the pulmonary arteries and veins, the superior vena cava, and the thoracic aorta. The inferior vena cava is classified as a lower vein.

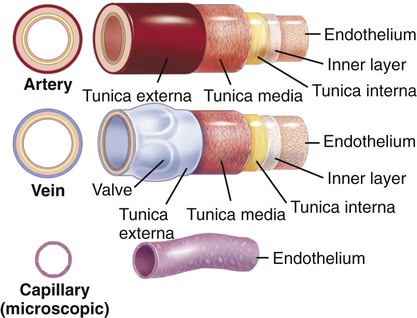

All of the vessels of the cardiovascular system (including the heart) share a lining of endothelial cells. While all carry blood, each type of vessel has a slightly different, but significant structure. Figure 9-3 illustrates these differences. The muscular, thick arteries are composed of three tunics, or coats: the outer layer is called the tunica externa (adventitia), the muscle layer and elastic layer are called the tunica media, and the inner layer is called the tunica interna (intima). Compare the thickness and structure of an artery to the thinner, valvular nature of veins. Veins do not have the thick muscle coat of the arteries to propel the blood on its journey through the circulatory system but instead rely on one-way valves that prevent the backflow of blood. In addition, skeletal muscle contraction provides pumping action. The capillaries have no coats, and their diameters are so tiny that only one blood cell at a time can pass through them.

9. endovascular _____________________________________________________________________________________

10. intravenous _____________________________________________________________________________________

11. pericardial ______________________________________________________________________________________

Anatomy and Physiology of the Cardiovascular System

Heart and Great Vessels

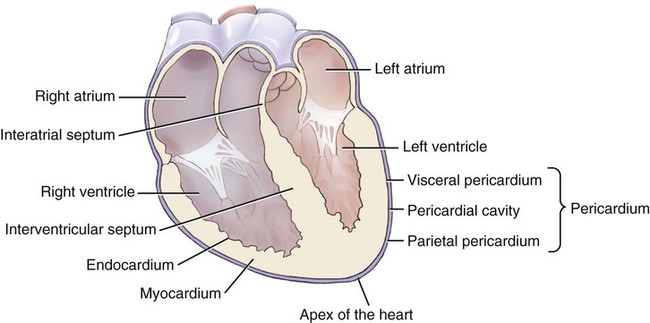

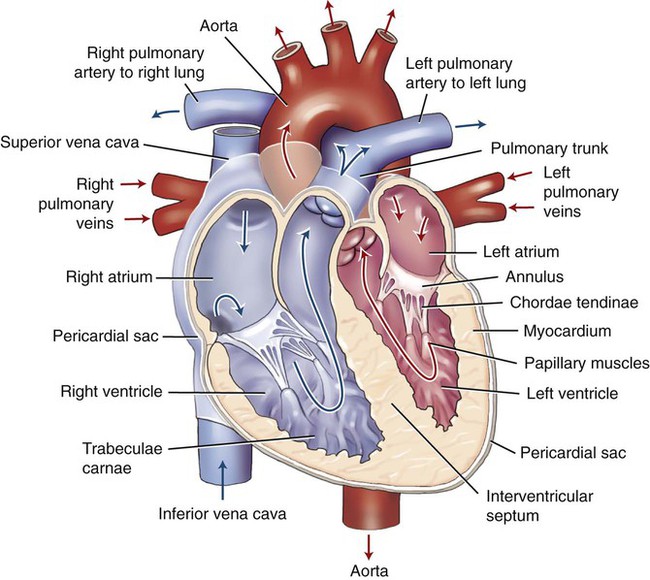

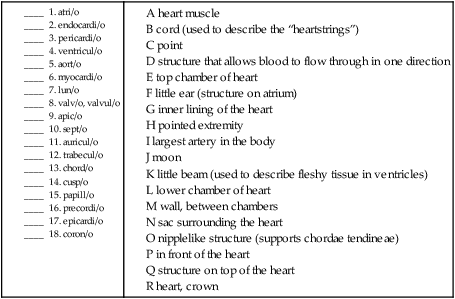

Inside, the heart has four chambers (Fig. 9-4). The upper chambers are called atria (sing. atrium). The ear-shaped pouch that is connected to each atrium is called the auricular appendage (see Fig. 9-6, B). Clinically, the right auricular appendage is associated with a rapid heartbeat (tachycardia), while the left auricular appendage is associated with blood clots from atrial fibrillation (an extremely rapid and irregular heartbeat). The lower chambers are called ventricles, which are composed of fleshy, beam-shaped structures called trabeculae carneae (see Fig. 9-5). Between the atria and ventricles, and between the ventricles and vessels, are valves that allow blood to flow through in one direction. The tissue wall between the top and bottom chambers is called the atrioventricular septum (pl. septa).

Coronary Circulation and Blood Flow Through the Heart

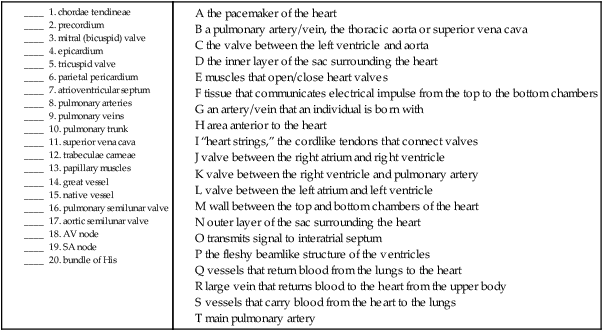

Using Figure 9-5 as a guide, follow the route of the blood through the heart. The picture and arrows in this diagram are shaded red and blue to represent oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. Deoxygenated blood is returned to the heart through the venae cavae. The superior vena cava returns blood from the upper body, whereas the lower body is drained by the inferior vena cava. Blood is squeezed from the right atrium (RA) to the right ventricle (RV) through the tricuspid valve (TV). Valves are considered to be competent (capable) if they open and close properly, letting through or holding back an expected amount of blood. Once in the right ventricle the blood is squeezed out through the pulmonary semilunar valve into the pulmonary arteries (PA), which carry deoxygenated blood to the lungs from the heart. These are the only arteries that carry deoxygenated blood. The main pulmonary artery (pulmonary trunk) divides into right and left arteries to supply each lung. The conus arteriosus is the cone-shaped extension of the right ventricle into the pulmonary trunk. In the capillaries of the lungs, the CO2 is passed out of the blood and O2 is taken in. The now-oxygenated blood continues its journey back from the lungs to the left side of the heart through the pulmonary veins (PV). These are the only veins that carry oxygenated blood. The blood then enters the heart through the left atrium (LA) and has to pass the mitral valve (MV), also termed the bicuspid valve, to enter the left ventricle (LV). When the left ventricle contracts, the blood finally pushes out through the aortic semilunar valve into the aorta (the largest artery in the body) and begins yet another cycle through the body. The first part of the aorta, the ascending aorta, rises toward the head, then bends into the aortic arch and continues downward through the chest as the descending thoracic aorta. Once it passes the diaphragm, it is termed the abdominal aorta.

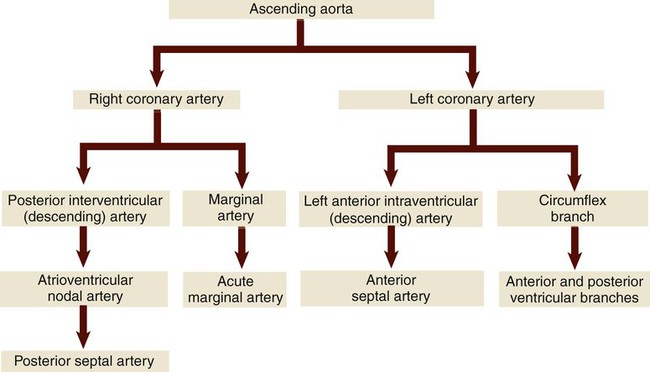

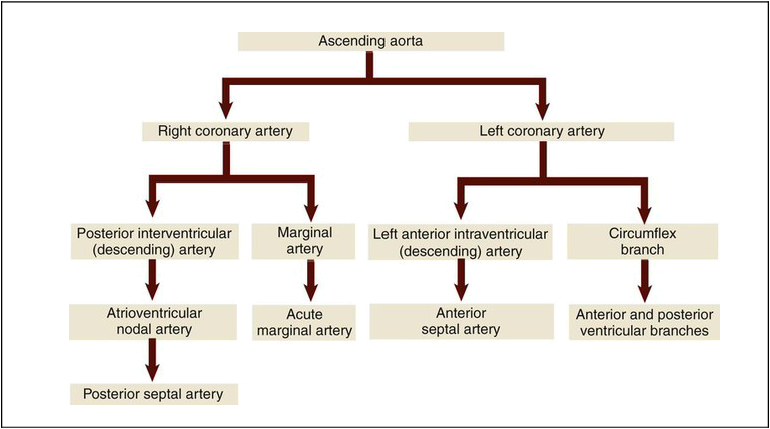

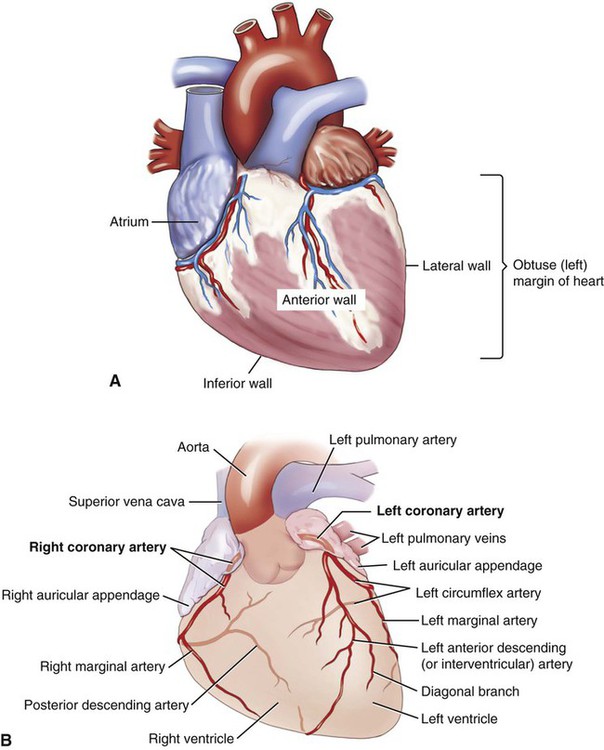

The heart muscle has its own dedicated system of blood supply, the coronary arteries (Fig. 9-6). The two main coronary arteries are called the left and right coronary arteries (LCA, RCA). The right coronary artery branches to form the posterior (interventricular) descending artery, which divides to form the atrioventricular artery and finally the posterior septal artery. The other main branch of the RCA is the marginal artery that divides to form the acute marginal artery. The left coronary artery branches to form the anterior (interventricular) descending branch, which continues to the anterior septal artery. It also forms a circumflex branch that divides into anterior and posterior ventricular branches. They supply a constant, uninterrupted blood flow to the heart muscle. Table 9-1 illustrates the path of blood through the coronary arteries. The return to the circulatory system is via the coronary veins, which deposit the deoxygenated blood into the coronary sinus, a small cavity where the blood is collected before it empties into the right atrium. The shallow grooves that hold these arteries on the surface of the heart are termed the left and right coronary sulci (sing. sulcus). In the human embryo, the sinus venosus is a hollow space that holds the blood as it returns to the heart. In normal development, the right side of the space becomes part of the right atrium. On the left side it becomes the coronary sinus and the oblique vein. One type of heart defect, an abnormal opening between the upper chambers of the heart (termed atrial septal defect) can result from abnormal development of the right side of this embryonic structure. The areas of the heart wall supplied by the coronary arteries are designated as the inferior, lateral, anterior, and posterior walls. The left margin (also called the obtuse margin) is formed mainly by the left ventricle. Table 9-1 shows where the blood goes after leaving the ascending aorta.

Conductive Mechanism System

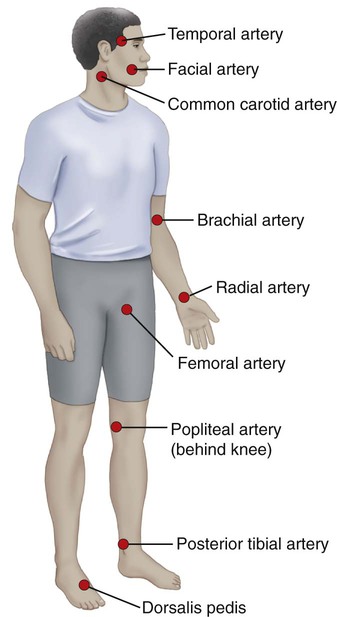

Systemic and pulmonary circulations occur as a result of a series of coordinated, rhythmic pulsations, called contractions and relaxations, of the heart muscle. The cardiac muscle is controlled by the autonomic nervous system, so (thankfully) the heart beats involuntarily. The normal rate of these pulsations in humans is 60 to 100 bpm and is noted as a patient’s heart rate. Figure 9-7 illustrates various pulse points, places where heart rate can be measured in the body. Blood pressure (BP) is the resulting force of blood against the arteries. The contractive phase is systole, and the relaxation phase is diastole. Blood pressure is recorded as systolic pressure over the diastolic pressure. Optimal blood pressure is a systolic reading less than 120 and a diastolic reading less than 80. Normal blood pressure is represented by a range. See the table below for blood pressure guidelines.

| Systolic | Diastolic | |

| Optimal | Under 120 and | Under 80 |

| Normal | 120-139 or | 80-84 |

| High-normal | 130-139 or | 85-89 |

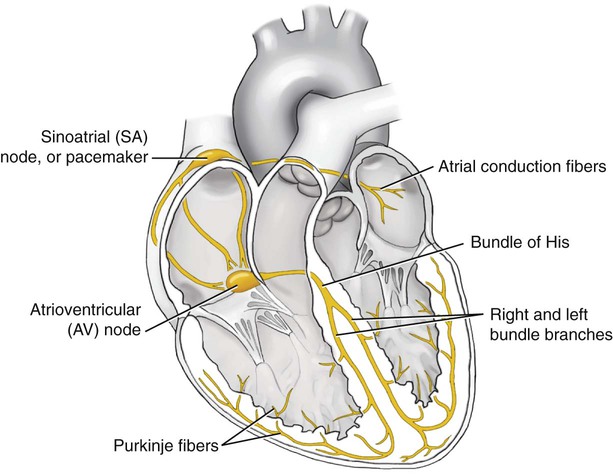

The cues for the timing of the heartbeat come from the electrical pathways in the muscle tissue of the heart (Fig. 9-8) termed the conductive mechanism. The heartbeat begins in the right atrium at the sinoatrial (SA) node, called the natural pacemaker of the heart. The initial electrical signal causes the atria to undergo electrical changes that signal contraction. This electrical signal is sent to the atrioventricular (AV) node, specialized cardiac tissue that is located at the base of the right atrium proximal to the interatrial septum. From the AV node, the signal travels next to the bundle of His (also called the atrioventricular bundle), which carries the electrical impulse from the top to the bottom chambers. This bundle is in the interatrial septum, and its right and left bundle branches transmit the impulse to the Purkinje fibers in the right and left ventricles. Once the Purkinje fibers receive stimulation, they cause the ventricles to undergo electrical changes that signal contraction to force blood out to the pulmonary arteries and the aorta. If the electrical activity is normal, it is referred to as a normal sinus rhythm (NSR) or heart rate. Any deviation of this electrical signaling may lead to an arrhythmia, an abnormal heart rhythm that compromises an individual’s cardiovascular functioning by pumping too much or too little blood during that segment of the cardiac cycle.

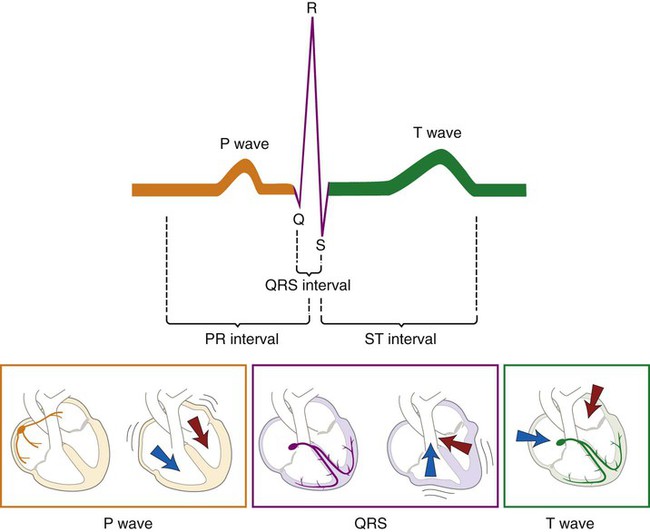

Figure 9-9 is a visual representation of the conductive mechanism of the heart through the use of an electrocardiogram (EKG/ECG). You can see the relationship of the electrical activity of the heart to the flow of blood through its chambers.

The ST segment is an indicator of heart muscle function. Figure 9-10 shows the comparison among the normal tracing of an ECG with the one from a STEMI (ST elevation myocardial infarction) and one from an NSTEMI (non-ST elevation myocardial infarction).

B. Match the structure in the heart and/or great vessels with its definition.

Arteries

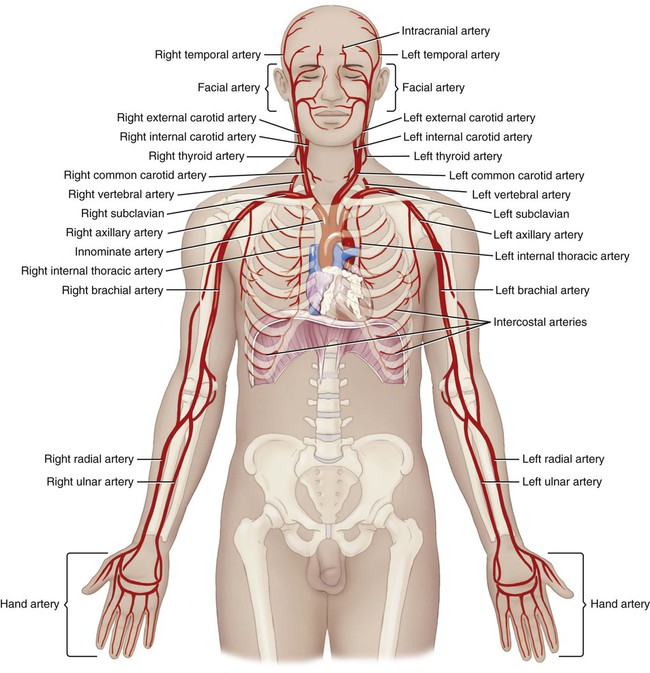

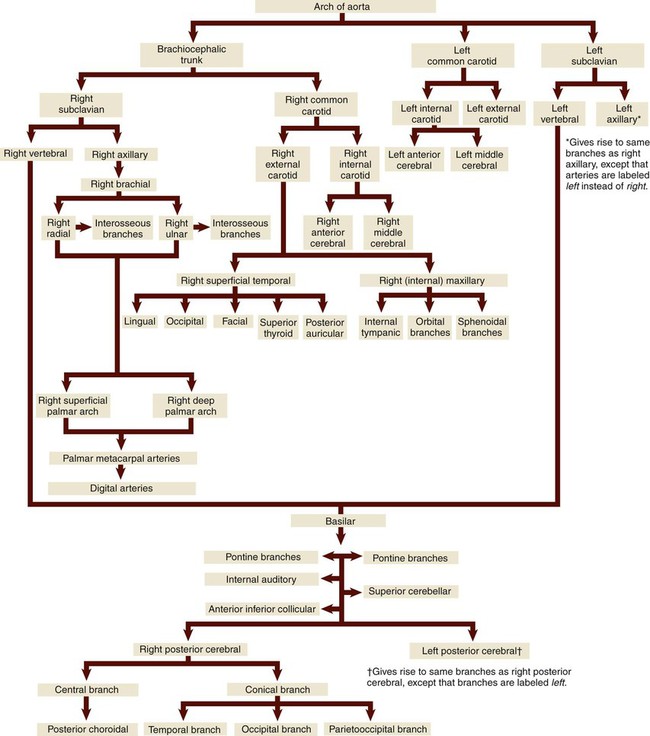

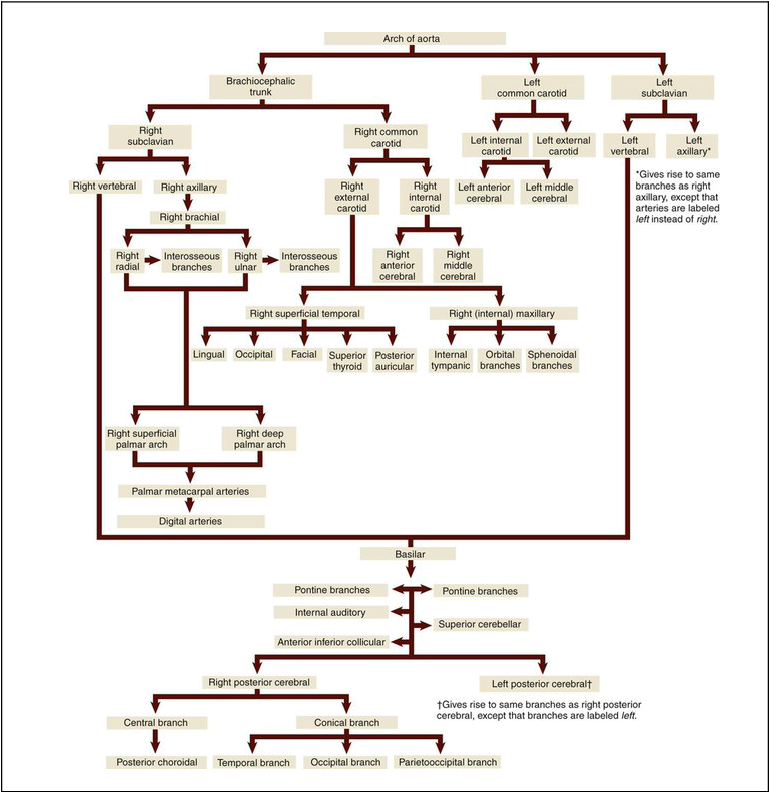

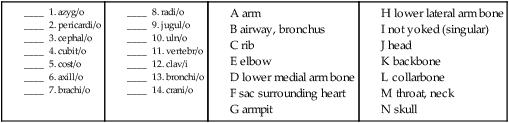

Upper Arteries

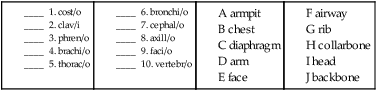

After leaving the aortic arch, the upper arteries (Fig. 9-11) branch toward the arms and head. The route of blood to the arms is slightly different on the right than on the left. On the right, the innominate (also called the brachiocephalic) artery is considered a first order branch.

The main blood supply to the chest is carried from the thoracic aorta to the right and left internal mammary arteries (also called the internal thoracic arteries [ITA]) that branch from the right and left subclavian arteries. The blood supply to the thyroid is divided in two. The superior thyroid artery receives blood from the external carotid artery and supplies the upper part of the gland. The inferior thyroid artery, which supplies the lower part of the gland, receives its blood supply from the right and left subclavian arteries. The intercostal, bronchial, pericardial, esophageal, mediastinal, and superior phrenic arteries supply blood to the expected organs and structures.* Table 9-2 illustrates blood flow through the upper arteries.

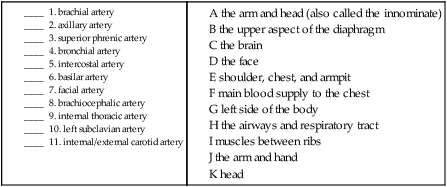

B. Match the upper artery named with the area that it supplies blood to.

Lower Arteries

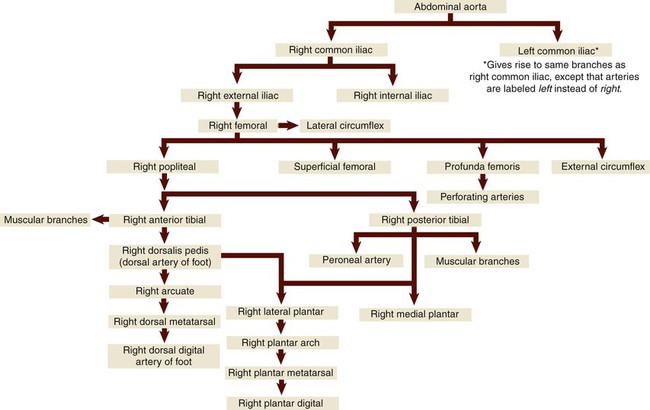

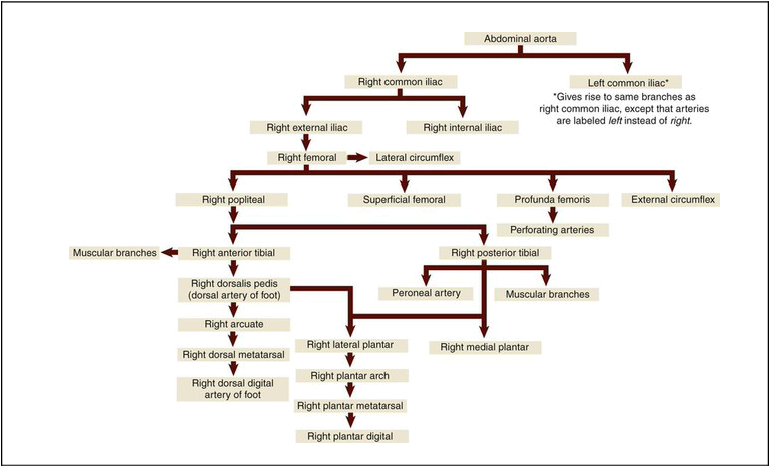

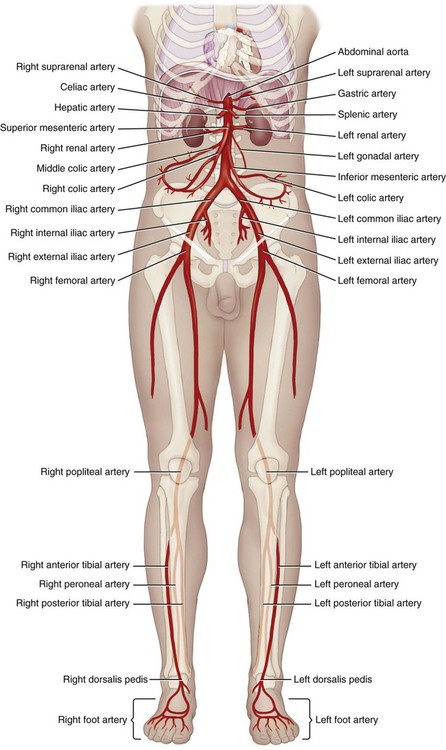

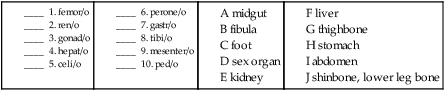

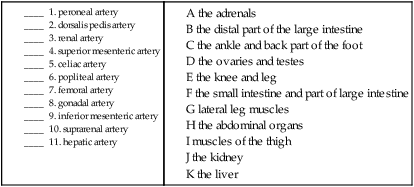

The lower arteries (Fig. 9-12) carry blood to the abdomen, pelvis, and legs. The first order celiac artery branches from the abdominal aorta into the second order left gastric artery (supplying blood to the stomach), the hepatic artery (liver), and splenic artery (spleen, pancreas, and stomach). The superior mesenteric artery, another first order branch, supplies the small intestine and part of the large intestine, then divides into second order right, middle, and left colic arteries that supply the large intestine. The first order renal arteries supply the kidneys, while another first order artery, the inferior mesenteric, supplies the distal end of the large intestine. The suprarenal arteries supply the adrenal glands located above (supra-) each kidney. The first order common iliac arteries supply the pelvis and lower extremities, then divide into the second order right and left internal iliac arteries (that supply the urinary and reproductive organs of the pelvis) and the external iliac arteries that supply the lower extremities. The right and left femoral arteries are branches of the external iliac arteries, and supply the muscles of the thigh. The popliteal arteries branch from the femoral artery and supply the knee and leg. The anterior and posterior tibial arteries are branches from the popliteal artery that supply the front and back of the lower leg. The peroneal artery is a branch from the posterior tibial artery and serves to supply blood to the lateral leg muscles. Finally, the arteries of the foot include the dorsalis pedis, which is a continuation of the anterior tibial artery and supplies blood to the ankle and dorsal part of the foot. Other arteries of the foot include the arcuate, tarsal, metatarsal, digital, and plantar arteries. Table 9-3 shows blood flow through the lower arteries. With the exception of the arcuate (meaning “bowed” or “curved”) artery, the other names should be familiar from musculoskeletal anatomy.

B. Match the lower artery with the area that it supplies blood to.

Veins

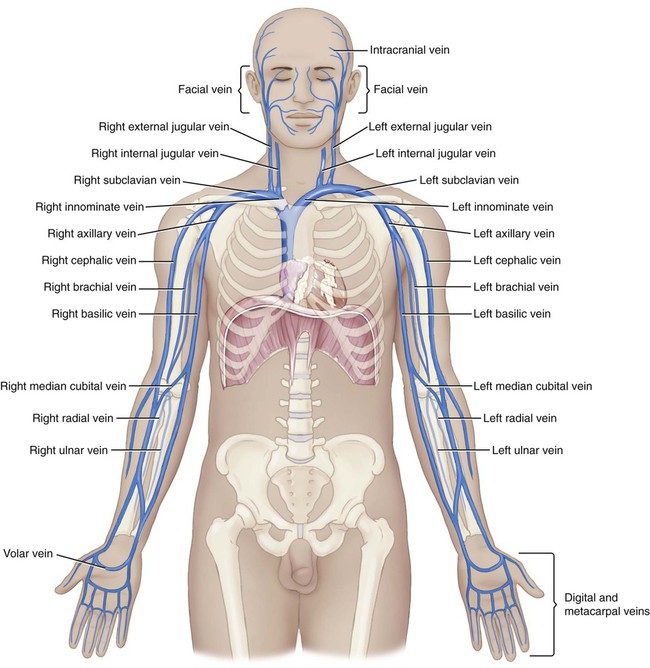

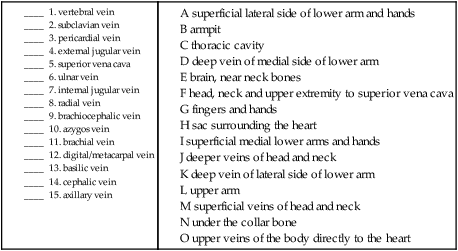

Upper Veins

The upper veins (Fig. 9-13) return blood to the heart from the head, neck, arms, and chest cavity. If you remember that the word parts for many of the veins tell you where they are returning blood from, you just need to pay special attention to which ones drain into the larger veins that collect blood from several different ones (e.g., the jugulars, brachiocephalics, and subclavians).

B. Match the upper veins with the areas that they drain blood from.

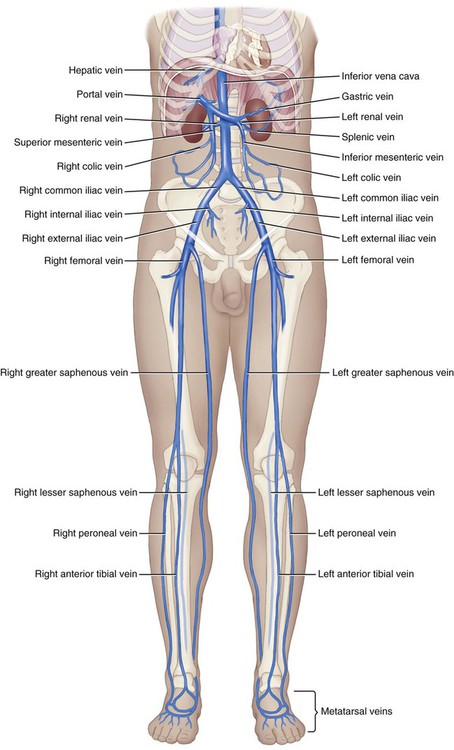

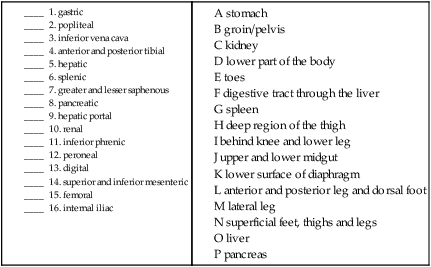

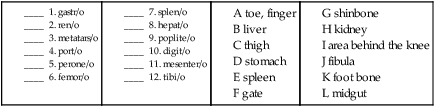

Lower Veins

The lower veins (Fig. 9-14) return blood to the inferior vena cava, collecting from the abdominopelvic cavity and legs.

B. Match the lower vein with the area that it drains blood from.