9 Circulation

Examination

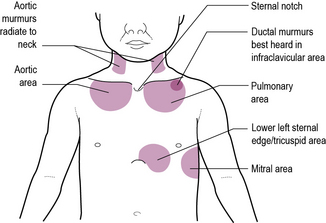

Ideally the examination can now proceed through inspection of the praecordium, palpation, auscultation and percussion, but in an active toddler you may need to grab opportunities to examine as they present. Remember that children who have had cardiac catheterization may have impalpable pulses and small scars in the groin or antecubital fossa over the femoral or brachial artery. Listen to the heart sounds at each of the four sites shown in Figure 9.1. At each site listen carefully for first and second heart sounds. In the pulmonary area it should be possible to hear the pulmonary and aortic components separately. An extra sound at the apex following the second sound is the third sound. This is usually physiological in children. In children with a cardiac failure there may be a gallop rhythm produced by third and fourth sounds. Finally, listen for heart murmurs. Try to decide where the murmur is best heard, how loud it is and whether it is a pansystolic (i.e. beginning with, and not separate from, the first heart sound) or an ejection systolic murmur. Diastolic murmurs are rare in childhood, but listen carefully all the same.

The following scheme is recommended.

Inspection

• Central cyanosis – look at the tongue; measure oxygen saturation if in doubt

• Jugular venous pressure – the short neck and skin folds in infants only allow this examination in older children

• Look at the chest wall for operative scars – a left or right thoracotomy scar may be easily overlooked because the incision is posterior and can be hidden by the arms – lift the arms and look round to the scapula

• Before examination, plot growth on the chart as children with heart disease may fail to thrive, and measure the respiratory rate.

Palpation

• Examine the hands and look for:

• The pulse – establish the rate, rhythm and nature of the pulse; in young children the brachial pulse is easier to identify than the radial pulse

• Feel for thrills over the chest wall and over the right carotid. Thrills palpable in the sternal notch can be present in both aortic or pulmonary stenosis.

Auscultation

Heart disease in infants

The neonate with a heart murmur

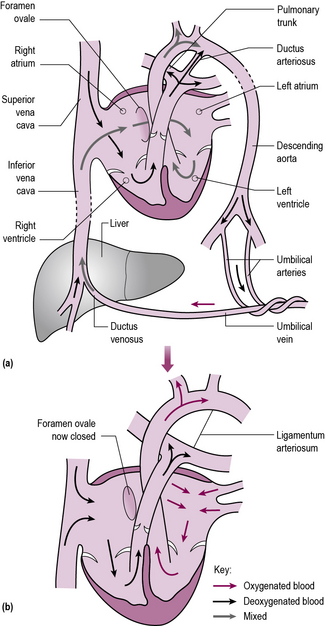

Changes in the circulation at birth (Figure 9.2)

1. The umbilical cord is clamped and cut, cutting off flow to and from the placenta.

2. The lungs become aerated and pressure in the pulmonary circulation drops.

3. Extra blood pours into the lungs as a result of this drop in pressure and returns via the pulmonary veins to the left atrium.

4. This changes the relative pressures in the left and right atria, and encloses the foramen ovale by a flap valve effect.

5. Normal lung function produces a marked rise in the oxygenation of the neonatal blood.

6. Muscles in the wall of the ductus arteriosus contract and lead to a physical, and later anatomical, closure of the duct.

7. The pulmonary pressure continues to drop over the first 1–2 months of life.

Figure 9.2 Changes in the circulation at birth. (a) The fetal circulation; (b) the newborn circulation.

The baby in Case 9.1 was urgently intubated and ventilated, and resuscitated with fluids – including saline and bicarbonate because of a severe metabolic acidosis. The differential diagnosis was thought to be overwhelming sepsis, congenital heart disease with cardiac failure or a metabolic disorder. In view of the impalpable femoral pulses, a prostaglandin E2 infusion was commenced. Coarctation of the aorta was confirmed by echocardiography and Edward was transferred urgently to a children’s cardiac unit.

Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction may arise from hypoplastic left heart syndrome, critical aortic stenosis or, as in Case 9.1, coarctation of the aorta. The left ventricle fails to eject blood into the obstructed aorta, and the circulation is maintained by blood flow through the ductus arteriosus, bypassing the obstruction. When the ductus arteriosus closes, catastrophic collapse occurs, with pulmonary oedema, pallor, shock and acidosis. In hypoplastic left heart syndrome, children are born without an effective left ventricle and rely on the right ventricle to perfuse both lungs and systemic systems. Using prostaglandin E2 to keep the ductus arteriosus open may sustain life until palliative surgery may be performed. There is practical and ethical debate as to the advisability of surgery for these children, as the prognosis remains guarded.

Children with neonatal cyanosis need an urgent diagnostic work-up (as in Case 9.2). If lung perfusion depends on a PDA, these children may deteriorate rapidly when the duct closes.

VSDs (such as in Case 9.3) are the commonest congenital heart defect. The communication between the ventricles leads to blood flow from the high-pressure left ventricle to the low-pressure right ventricle. Infants do not usually present in the neonatal period when the left and right pressures are similar, but, as the pulmonary artery pressure drops, pulmonary blood flow increases with resultant pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary oedema.

Heart disease in children

The older child with a heart murmur

The innocent murmur

Innocent ejection systolic murmurs are caused by turbulent blood flow within any part of the circulation. See Box 9.1 for the characteristics of innocent murmurs.

Arrhythmias

If the complexes on the ECG are narrow, as in Case 9.4, the arrhythmia is most likely to be a supraventricular tachycardia – the commonest pathological childhood arrhythmia. Broad complex tachycardia may be supraventricular or ventricular in origin. If the heart beats fast enough there is no time for refilling and the circulation fails, as in this case. It can occur at any age, including in utero, when treating the mother may control it. There is rarely a structural defect. Management is to restore sinus rhythm with vagal manoeuvres, medication or if necessary DC cardioversion (see Appendix I, p. 287).

Rare problems

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever is the commonest cause of heart disease in children worldwide. It is a complex multisystem disease which may involve the heart, joints, nervous system and skin with various non-specific inflammatory changes (see Chapter 6, p. 57).

Sudden cardiac death in childhood

Sudden cardiac death in childhood is exceptionally rare. It may follow:

• Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

• Inherited prolonged QT syndromes

• Late complication of Kawasaki’s disease due to occlusion of coronary aneurysms (see Chapter 16, p. 238)

• Commotio cordis – ventricular fibrillation triggered by a sudden blow to the chest, usually during sport. It is much more common in males, with a mean age of death of 15 years. Defibrillation is life-saving.