Circuit C

STATION 1

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

STATION 2

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

STATION 3

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

STATION 4

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

STATION 5

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

CLINICAL SCENARIO

On general inspection the child is pale and looks small for his age. He is playing with a toy in his mother’s arms and you notice an abnormality to his right hand. On closer inspection he appears to have two thumbs but both are hypoplastic. The more proximal lacks a distal phalangeal segment and the distal is attached by only a small piece of skin (see Fig. 3).

What more do you want to examine in his upper limbs?

After presenting your findings, which other parts of the body will you examine?

STATION 6

This station assesses your ability to assess specifically requested areas in a child with a developmental problem:

STATION 7

This station assesses your ability to communicate appropriate, factually correct information in an effective way within the emotional context of the clinical setting:

STATION 8

This station assesses your ability to communicate appropriate, factually correct information in an effective way within the emotional context of the clinical setting:

STATION 9

This station assesses your ability to take a focused history and explain to the parent your diagnosis or differential management plan:

COMMENTS ON STATION 1

DIAGNOSIS: AORTIC STENOSIS

It would be nice if every child seen in the cardiovascular station has obvious signs and symptoms – but they don’t. You may have a child with an unusual congenital heart defect whose abnormality is impossible to determine on clinical examination. So it is important to know what to rule out if your child has a murmur of indeterminate origin.

Did you remember to ask the examiner to check peripheral pulses and perform a blood pressure?

REMINDERS

Turner’s syndrome (full details can be found on p. 184) 5X (although mosaicism possible)

Cardiac disorders are the cause of increased mortality in this syndrome

Aortic coarctation most common cardiac defect

Dental malocclusion increased, so prophylaxis vital

Predisposition to keloid scar formation (child may have cardiac surgical scars)

Indication for using growth hormone (and consider using steroid to increase final height).

| Aortic stenosis | Tips |

|---|---|

| Exam | Apex beat (do you always examine this?) may be displaced |

| Suprasternal and carotid thrill | |

| Systolic murmur in aortic region and left sternal edge | |

| Have you felt for peripheral pulses? (Associated with coarctation) | |

| The slow rising pulse is a very difficult sign to elicit | |

| Have you listened to the back? (Not always helpful but there shouldn’t be radiation, unlike in coarctation) | |

| A budding cardiology professor may pick up the diastolic murmur of aortic incompetence, which is more likely to occur post-surgery | |

| Investigation | ECG normal in the well child but may show signs of left ventricular hypertrophy: |

Oestrogen therapy to allow development of secondary sexual characteristics.

Williams’ syndrome (also see p. 37)

Supravalvular aortic stenosis and peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis

CAN YOU …

Talk through the examination features of aortic stenosis?

If shown an ECG what would you look for?

What features would you look for if told the cause of the aortic stenosis was related to a syndrome?

COMMENTS ON STATION 2

DIAGNOSIS: INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

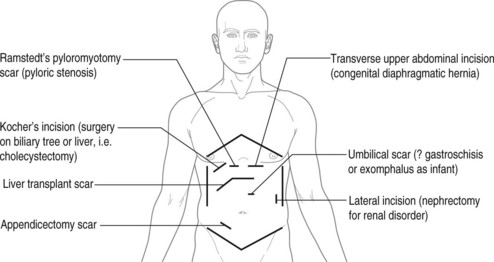

It is potentially possible to complete a large proportion of your SHO training with little experience of surgery and scars. Severe inflammatory bowel disease is generally treated by specialist gastroenterologists and surgeons and unless you have done a specific attachment your experience may be limited to the textbook. Knowledge of common surgical scars will either impress examiners or save embarrassment, depending on which way you look at it!

| Nutritional assessment | Notes |

|---|---|

| General | Weight /height /BMI |

| Nasogastric placement | |

| Long-term venous access | |

| Does the patient look well? | |

| Storage | Subcutaneous fat (mid-arm, subscapular and axillary) |

| Muscle bulk (biceps, triceps and quadriceps) Prominence of iliac bones | |

| Face | Pale conjunctiva |

| Oral ulceration Dental caries | |

| Skin | Liver disease and vitamin deficiency demonstrated by jaundice and bruising |

| Rashes | |

| Excoriations | |

| Erythema nodosum | |

| Hands | Pallor (of palmar creases) |

| Clubbing of fingers | |

| Palmar erythema | |

| Koilonychia (dystrophy of the fingernails in which they are thinned and concave with raised edges; ‘spoon-shaped nails’) | |

| Leuconychia (white spots on the nails) | |

| Abdomen | Distension |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | |

| Surgical scars | |

| Other | Gait examination: tests strength and any neurological impairment |

| Blood pressure and pulse (standing and lying to measure postural change) | |

| Urinalysis and stool analysis as appropriate Pubertal assessment |

[Aphthous ulcer: a shallow individual ulcer that is round or oval in shape. The ulcer will usually be no more than ¼ inch in diameter. The centre of the ulcer will be covered with a loosely attached white or greyish membrane. The edges of the ulcer will be regular (non-jagged) and surrounded by a reddish halo. The tissue adjacent to the ulcer will be healthy in appearance.]

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Tips |

|---|---|

| Exam | Weight/height/BMI/head circumference |

| Clubbing (rare) | |

| Cushingoid appearance or striae | |

| Scars from acute surgery (obstruction) or non-acute surgery (growth failure, debilitating symptoms, colectomy/pouch or prevention of malignancy), perineum, looking for anal fissures and skin tags | |

| Investigations | Blood tests: |

| (Leucocytosis, raised ESR, low protein, renal impairment, consider vitamins and minerals in long-term follow-up) | |

| Stool: | |

| Culture to exclude other diagnoses | |

| α1-Antitrypsin (reflects bowel protein loss) | |

| Imaging/endoscopy: | |

| Left wrist X-ray for bone age | |

| AXR acutely | |

| Barium meal/follow-through dependent on position of lesion | |

| Management: Crohn’s | Multidisciplinary approach |

| Use of steroids (orally or intravenous) | |

| Aware of sulfasalazine for small bowel disease | |

| May need steroid sparing agents: azathioprine, ciclosporin or methotrexate | |

| Nutritional therapies including use of overnight feeds | |

| Management: ulcerative colitis | Multidisciplinary approach |

| Steroid enemas or oral steroids | |

| Sulfasalazine for acute situation | |

| Yearly colonoscopy when disease > 10-15 years |

‘I have examined John, who is a 15-year-old boy but appears underweight and small for his age. I would like to plot his height and weight on a growth chart. There appears to be peripheral muscle wasting and I need to assess this formally with skin-fold callipers and mid-arm circumference. He has pale conjunctivae but no obvious oral ulceration. There are no invasive feeding or intravenous lines. On abdominal examination there is a surgical scar consistent with a laparotomy but his abdomen is otherwise soft, with no masses. He has some diffuse tenderness at the left iliac fossa but no guarding. It would be useful to examine his peri-anal region for evidence of fissures or skin tags.’

A laparotomy scar will run transverse through the centre of the abdomen (see Fig. 4).

COMMENTS ON STATION 3

DIAGNOSIS: SYDENHAM’S CHOREA

The art of observation before examination is persistently stressed throughout your medical training. Although you may not have done this as a medical student it is essential you have the ability to ‘hang back’. Engaging your brain before putting your mouth in gear will stop you blurting out an answer you will be unable to defend.

| Chorea | Notes PASS |

|---|---|

| Anticonvulsant side effect | |

| Cerebral palsy – dyskinetic | Look specifically for athetosis (slow writhing movements) as cerebral palsy is the commonest cause of this |

| Assess intellectual impairment, spastic posturing and gait | |

| Sydenham’s chorea | Acute-onset choreiform movements |

| May have ‘milkmaid’s grip’ – inconsistent hard and weak grasp of examining finger | |

| Extended hands tend to pronate | |

| Anaemia, leucocytosis and potential increased ESR | |

| Check ASO titre | |

| Throat swab for Group A haemolytic streptococci There may be a psychological element (emotional lability and depression) | |

| Treat with dopaminergic blockers (haloperidol) | |

| Remember this is a major manifestation of rheumatic fever and so is likely to need antistreptococcal rheumatic fever prophylaxis | |

| Wilson’s disease | Family history (autosomal recessive) |

| Difficulty excreting copper in bile | |

| Low ceruloplasmin and increased urinary excretion of copper | |

| Evidence of liver failure (must examine abdomen of children with chorea) | |

| Copper chelate with D-penicillamine | |

| Degenerative conditions (?appropriate for exam) | Huntington’s disease, Lesch-Nyhan, Moyamoya |

The following websites have video clips of choreiform movements and tics. The former is a superb revision aid, especially for developmental progression in the under-2-year-old (go to pediNeurologic exam):

library.med.utah.edu/neurologicexam/html/gait_abnormal.html

www.kcom.edu/faculty/chamberlain/Website/lectures/lecture/image/chorea.mov

1. Haloperidol can be useful in dampening down the involuntary spasms but unfortunately can actually make the movements worse.

2. The most important side effect is oculogyric crisis. This may cause the patient to have very forceful movements of their neck and head associated with rolling movements of the arms.

3. To prevent the above the dose of haloperidol must be initially small and increased slowly. If there are reactions, ceasing medication will prevent long-term problems.

Criteria for diagnosis of rheumatic fever (need two major or one major and two minor plus evidence of streptococcal disease)

| Major | Plus |

| Carditis | Increased titres of antistreptolysin O |

| Polyarthritis | Positive throat culture for Group A streptococci |

| Sydenham’s chorea | |

| Erythema marginatum | |

| Subcutaneous nodules (not erythema nodosum) | |

| Minor | After acute episode |

| Previous rheumatic fever | Need regular penicillin |

| Polyarthralgia | Follow-up of possible valvular damage |

| Fever | |

| Elevated CRP, ESR, WCC | |

| Prolonged P-R interval |

COMMENTS ON STATION 4

DIAGNOSIS: RIGHT BASAL PNEUMONIA

• what the child looks like at rest;

• whether the child is well grown;

• what items are around the bed;

• where the pathology is – make sure you are definite and have not confused right and left!

• what the pathology is – e.g., there is clubbing, not there may be clubbing.

This child is recovering from a right basal pneumonia but in order to make this diagnosis you must also know:

COMMENTS ON STATION 5

DIAGNOSIS: FANCONI’S ANAEMIA

| Fanconi’s anaemia | Notes |

|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | Anaemia causing weakness |

| Neutropenia causing infections | |

| Thrombocytopenia causing bleeding and bruising | |

| Commonly have abnormal pigmentation of the skin | |

| May have short stature with skeletal malformations (absent thumb and radius – check it’s there!) | |

| Renal anomalies | |

| Laboratory findings | Macrocytic anaemia |

| Thrombocytopenia precedes severe aplastic anaemia | |

| Rule out idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | |

| Complications | Generally related to haematological dysfunction but there is also a significant risk of developing a malignancy, especially leukaemias and solid tumours |

COMMENTS ON STATION 6

DIAGNOSIS: TREACHER COLLINS SYNDROME

Do you know your syndromes? For this case it actually doesn’t matter, as you were asked to ‘assess this child’s speech and language’. In fact, it is very important not to get distracted by the obvious abnormalities. Even knowing the syndrome, if you cannot do a quick assessment of speech and hearing you will not be gaining the marks. Remember the College specifically say they are not testing you against the trained developmental paediatrician but the first-year registrar. Accepting this child is unlikely to present to an outpatient clinic at this age with concerns about speech and language, this must still be the approach to take.

| At 5 years | |

| Gross motor | Stands on one foot for up to 10 seconds (and can therefore hop) |

| Interest in climbing | |

| May be able to skip | |

| Fine motor and vision | Copies triangle |

| Draws person with body details | |

| Uses fork and spoon but not knife | |

| Speech and hearing Can count 10 objects | |

| Knows if morning or afternoon Can read words | |

| Social | Knows name and address |

| Can use large buttons in dressing and undressing | |

| Knows right and left hand | |

| Can do simple household tasks (helps with dishes) |

CAUSES OF SPEECH DELAY

TYPE OF HEARING TEST

| •Distraction tests | 6–12 months |

| •Speech discrimination tests | 2–4 years |

| •Performance tests | 24–30 months |

| • Pure tone audiometry | 4–5 years |

| • Electrical response audiometry | Neonate |

| • Brain stem auditory evoked responses | Neonate |

| •Evoked otoacoustic emissions | Any age |

COMMENTS ON STATION 7

1. Introduce yourself and explain what you are going to do.

2. Ask for previous knowledge teaching.

3. Explain you are just doing basic airway management and help has been called for.

5. Show airway technique (chin lift, jaw thrust).

6. Assess breathing (look, listen, feel).

7. Five rescue breaths if no breathing.

8. Assess circulation (brachial or femoral). Commence chest compression if no pulse or pulse less than 60.

9. Show cardiac compression (heel of one hand over the lower third of the sternum, one finger breadth above the xiphisternum).

10. Commence CPR at 15:2 ratio until help arrives. Compression rate 100 per minute.

Make sure you are familiar with the latest Advanced Paediatric Life Support Guidelines.

COMMENTS ON STATION 8

Although this may seem like an unlikely scenario and not particularly the duty of a first-year registrar, there are many times when family members have certain questions which are appropriate for you to answer. The brain stem death test is not something which will be carried out by a registrar but is something with which you should at least be aware. The essence of this case is how you approach the very sensitive issue of death. The principles of good preparation are vital. You must introduce yourself with full name and position. Tell Mark you have diverted your pager and ask if he would like anyone else present. It may be worthwhile suggesting a nurse accompany you.

Mark is likely to want to know what the test involves (see below) and who will be carrying it out.

| Establish cause of disease/injury and: | |

|---|---|

| Coexistence of coma and apnoea | Apnoea test; observe for 3 minutes with PCO2 > 60 mmHg |

| Absence of brain stem function | Fully dilated pupils with no light response |

| Absence of spontaneous eye movement and those produced by doll’s eye movements and water instillation in external auditory meatus | |

| Corneal and gag reflexes absent | |

| Normal blood pressure and temperature | |

| Flaccid muscle tone, no spontaneous movement | |

| Exam consistent through observation period | Two exams over 12–24 hours |

COMMENTS ON STATION 9

In may be argued that specialist diabetic management does not fall within

| History | Notes |

|---|---|

| Initial diagnosis | Age |

| Intervention needed (?PICU) | |

| Length of hospital stay | |

| Education given | |

| Past management history | Number of hospitalisations (including PICU) |

| Frequency of monitoring | |

| Changes of management | |

| Complications of treatment (lipohypertrophy, hypoglycaemic episodes) | |

| Current treatment | Type of insulin and duration of this treatment |

| Modifications for sport, etc. | |

| Frequency of monitoring | |

| Dietary adaptations (is there a dietician involved?) | |

| Social history | Effects on child: |

| Understanding of disease and long-term complications | |

| Effects on friends and school: | |

| Any involvement in diabetic camps/groups? | |

| Effect on family: | |

| Siblings’ understanding of disease | |

| Involvement of social worker | |

| Change of family’s diet |

Monitoring may well be less rigid than previously and at this stage in Steven’s life a night spent drinking has much more short-term gain than long-term good glucose control! It is important to give encouragement rather than chastisement. Management of psychological issues must make use of 98 the whole family and may involve support groups or individual counselling in some cases. Diabetic nurses/social workers are an essential resource but should not be assumed to be involved.

whether there is any evidence of immunodeficiency (must ask if child immunised);

whether there is any evidence of immunodeficiency (must ask if child immunised); Cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy