Circuit B

STATION 1

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

STATION 2

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

STATION 3

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

STATION 5

This station assesses your ability to elicit clinical signs:

STATION 6

This station assesses your ability to assess specifically requested areas in a child with a developmental problem:

CLINICAL SCENARIO

Gross motor: Although able to sit up without support, she is unable to stand. With her hands held there is an effort to pull up but she doesn’t yet have the strength in her legs. She will roll from front to back or back to front. Her general tone is good and there is no evidence of spasticity.

Fine motor: If she drops her rattle she is able to pick it up (in either hand) with a palmar grasp.

Hearing/language: She responds to her mother’s voice by looking at her. You are not given time to do a formal distraction test. She makes noises but no distinguishable words.

Social: She smiles and shows little fear of you. When given a spoon she accidentally hits herself over the head with it.

General: She appears small for her age, and has the composition of an approximately 6-month-old child. There are no dysmorphic features but she does have a plagiocephalic skull and scars on her hands.

STATION 7

This station assesses your ability to communicate appropriate, factually correct information in an effective way within the emotional context of the clinical setting:

STATION 8

This station assesses your ability to communicate appropriate, factually correct information in an effective way within the emotional context of the clinical setting:

STATION 9

This station assesses your ability to take a focused history and explain to the parent your diagnosis or differential management plan:

COMMENTS ON STATION 1

DIAGNOSIS: DOWN’S SYNDROME WITH AVSD

Children with Down’s syndrome are commonly utilised in exams as they may have multiple pathologies but are gifted with an extremely pleasant temperament. It is a syndrome you should know inside out and back to front.

The apex was near the mid-axillary line and therefore this child has cardiomegaly.

The second heart sound is louder, indicating a degree of pulmonary hypertension.

The absence of a thrill makes an AVSD more likely (although if the VSD is severe the thrill may be absent and an AVSD may have a thrill).

No mention of a diastolic murmur but a diastolic flow murmur may well be present at the apex of lower left sternal edge.

Treatment will involve diuretics but only surgery will be curative.

CLASSIC FEATURES IN DOWN’S SYNDROME

COMMON ASSOCIATIONS OF DOWN’S SYNDROME

T Thyroid problems (hypothyroid)

I Instable atlanto-axial joint

Y Y chromosome (males) – infertile

REMINDER

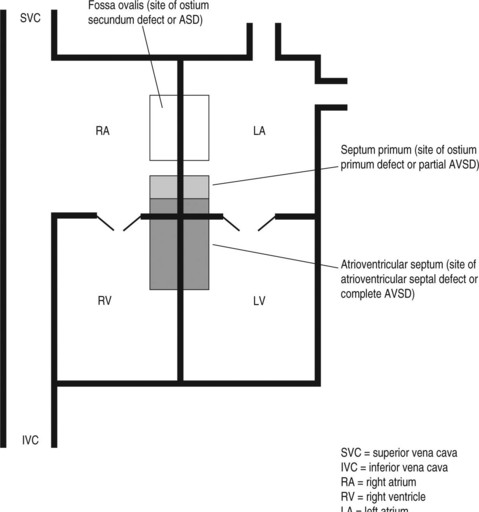

A quick review of the anatomy may be helpful (see Fig. 1).

Lesions can also be inferior to the site of the ostium secundum and just touch the upper part of the ventricular septum. This is called an ostium primum ASD or may be referred to as an incomplete AVSD. Although the ventricular septum is intact, there are invariably abnormalities of the atrioventricular valves (often a mitral valve cleft).

CAN YOU …

| Ostium primum partial (AVSD) | Ostium secundum (ASD) |

|---|---|

| Soft ejection systolic murmur at left second intercostal area | Soft ejection systolic murmur at left second intercostal area |

| May have murmur at apex secondary to mitral regurgitation | |

| Left axis deviation | Right axis deviation |

| Partial right bundle branch block | Partial right bundle branch block |

COMMENTS ON STATION 2

DIAGNOSIS: GLYCOGEN STORAGE DISORDER

This child has a glycogen storage disorder (GSD) which, if your revision is going very well, you will know is most likely to be von Gierke’s disease (GSD type 1). If you are lucky enough to have seen a child with this condition and are able to recognise ‘doll’s face facies’ then in the real exam this station may be much easier. Many classic facial appearances, the prominent forehead of Alagille’s syndrome, the saddleshaped nose of fetal alcohol syndrome and the triangular appearance of Russell-Silver syndrome will not be readily apparent to you in the exam. The examiner is not going to fail you for missing these features (although it would be difficult to justify missing a Down’s syndrome unless the appearance was very subtle). It is much more important to pick up the hard clinical signs and put them in their correct context rather than be a good syndrome spotter. This child has impressive hepatomegaly without the presence of splenomegaly. The only evidence of chronic liver disease is the bruising, but overt liver failure seems unlikely given the absence of jaundice (and the child’s presence in the exam!). If you had not thought of storage diseases an appropriate response would be:

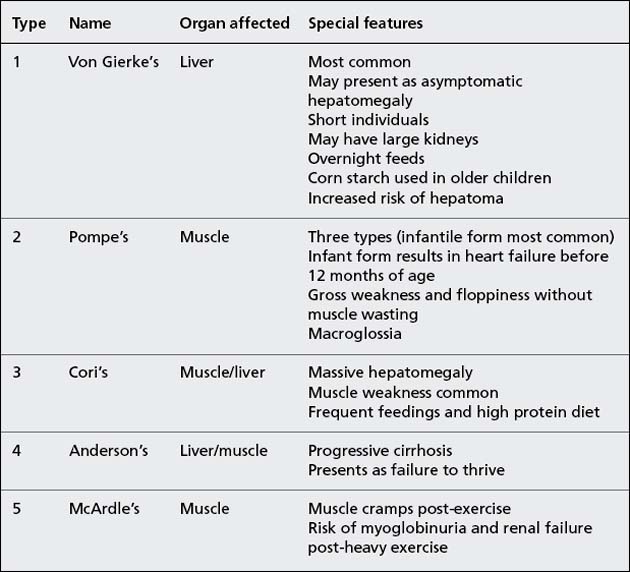

Some key features of the glycogen storage disorders are worth knowing as they are stable patients with good signs, making them popular exam patients. It is worth looking at the size of the patient’s tongue as 58 macroglossia is associated with Pompe’s disease (GSD type 2). Asking the mother if Sarah has a problem with her sugar levels should clinch the diagnosis of GSD.

| Hepatomegaly alone | Splenomegaly alone | Hepatosplenomegaly |

|---|---|---|

| Glycogen storage disorders | Portal hypertension | Myeloproliferative disorder |

| Red blood cell defect (hereditary spherocytosis,sickle cell anaemia) | Mucopolysaccharidoses | |

| Heart failure | α1-Antitrypsin deficiency | |

| Galactosaemia | ||

| Wilson’s disease | Chronic ITP |

COMMENTS ON STATION 3

DIAGNOSIS: SPINA BIFIDA

| Medical | Functional | Social |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrocephalus (presence of shunt, CSF infection) | Mobility (need for wheelchair or callipers) | Education (need for special class or school if intellectual impairment) |

| Orthopaedics (callipers, contracture release) | Incontinence (use of anticholinergics) | Development |

| Adolescent issues | ||

| Ulcers (pressure sores) | MDT involvement (Physio/OT) | |

| UTIs (increased risk of reflux) | ||

| Scoliosis/kyphosis | ||

| Eyes (ambylopia secondary to squint) |

COMMENTS ON STATION 4

DIAGNOSIS: MARFAN’S SYNDROME

A station with the potential for so many positive clinical findings is an ideal examination case but the candidate must be careful to remember them all when presenting in the heat of the moment. The findings of arachnodactyly, tall height and scoliosis should make you consider whether she has Marfan’s syndrome. Had you examined her oropharynx you would have noted a high-arched palate. The degree of kyphoscoliosis or chest wall deformity may produce problems in respiratory function resulting in a picture of restrictive lung disease.

| Tips | |

|---|---|

| Genetics | Autosomal dominant with variable expression, chromosome 15 |

| Features | Skeletal: arachnodactyly Tall stature Lower segment > upper segment Arm span > height Scoliosis High-arched palate Joint hypermobility Sternberg’s sign (can adduct thumb across palm) CVS: aortic dissection Mitral valve prolapse RS: pneumothorax Eyes: lens dislocation |

| Management | Regular ECHO and BP measurement. Ocular examination Prognosis affected by cardiac lesion |

| Differential | Homocysteinuria: thrombosis, learning difficulties, osteoporosis and homocysteine in urine Klinefelter’s syndrome Acromegaly (rare) |

| In the following conditions the final adult height is usually normal despite a greater rate of growth as a child: Soto’s syndrome Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome Hyperthyroidism Precocious puberty |

|

| Familial tall stature is the commonest cause of tall stature, although the examiners much prefer showing children with signs! |

COMMENTS ON STATION 5

THYROID EYE DISEASE

• Exophthalmos: An abnormal protrusion of the eyeball. Some texts interchange the term for proptosis, others preferring to use exophthalmos for an endocrinologically caused protrusion. Looking from above the child’s head for a forward eye bulge is not a terribly objective exam but it is obvious to the examiner what you are trying to do.

• Lid retraction: The sclera above the iris is visible at rest. If not present, test for lid lag.

• Lid lag: Ask the child to follow a horizontally placed finger up and down. If you are able to see the sclera above the iris on downward gaze this sign is positive.

• External ophthalmoplegia: Uncommonly the lateral or superior rectus muscles may be affected.

Examination

| General appearance | Must ask for weight and height Asking for height velocity shows insight into condition Pendred’s syndrome is a goitre (not necessarily hypothyroidism) and hearing loss. Look for hearing aid A horizontal necklace scar indicates a thyroidectomy (so check voice for hoarseness) Ask about pubertal staging |

|

| Inspection | Ask the child to take a drink – the gland should rise on swallowing Ask the child to stick his/her tongue out – a thyroglossal cyst will rise with this procedure |

|

| Palpation | Palpate from behind the child (and again while they drink) As with all lumps: Shape Size Softness Surface (one or multiple lumps) |

|

| Other gland examination | Local lymphadenopathy Percuss sternum and palpate suprasternal notch for retrosternal extension Auscultate the murmur for a bruit |

|

| Thyroid status (head to toe) | Hypothyroid | Hyperthyroid |

| Swollen eyes with eyebrow loss | Classic eye signs | |

| May have goitre bruit | ||

| Thin, dry hair and skin | Tachycardic | |

| Bradycardic | Warm, sweaty hands | |

| Cool peripheries | Proximal muscle weakness | |

| Hyporeflexic | Wide pulse pressure | |

History

| Hypothyroid | Hyperthyroid |

|---|---|

| Do teachers describe your child as an attentive pupil? | Does you child have problems sleeping? |

| Has school performance deteriorated after treatment? | Has you child ever complained of palpitations? |

| Has you child had any problems with constipation? | Has your child become emotionally labile? |

| Does your child feel the cold more than their siblings? | How is your child performing at school? |

| Has you child started to gain weight recently? Has your child had any difficulty walking? (slipped upper femoral epiphysis) |

• Autoimmune (increased incidence in girls)

• Family history may be present

• Associated with diabetes mellitus

• Graves’ disease (productions of antithyroid antibodies)

• TSH low and T4 high at diagnosis

• TSH receptor-stimulating antibodies can be shown to regress on remission

• Treat with carbimazole over 2-year period, although relapse rate is high

• Propranolol can be used for acute symptoms

REMINDER

| Midline | Lateral |

|---|---|

| Thyroglossal cyst | Lymphadenopathy (primary or secondary) |

| Epidermoid cyst | Cystic hygroma |

| Branchial cyst | |

| Sternomastoid ‘tumour’ (neonatal) |

COMMENTS ON STATION 6

DIAGNOSIS: EX 27-WEEK NEONATAL GRADUATE

It has been emphasised that knowledge of your milestones is paramount and your recall must be a reflex. You must see each particular movement, 66 noise or skill a child makes as an age. This is very easy to practise. Walk around any supermarket on a weekend afternoon and guess the ages of children. I do not recommend asking the parents how old their child actually is as someone might call the police! You will quickly realise what knowledge you have to hand and what you can’t remember.

This child has a developmental age of at least 6 months:

and shows some features of a 9-month-old:

and is obviously not the developmental equivalent of a 1-year-old child.

| Cause of developmental delay | Examples |

|---|---|

| Congenital/syndromic | Down’s syndrome |

| Central neurological | Isolated motor delays (e.g. the bottom shuffler) |

| Idiopathic mental retardation | |

| Peripheral neurological | Muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy |

| Familial | |

| Environmental/social | Parental neglect Malnourished |

It is vital in the history to have a good documentation of the timeline of growth and development. A good history that skills have been lost raises the possibility that the child has a neurodegenerative or metabolic condition, whereas the failure to obtain skills may represent a primary neurological condition.

COMMENTS ON STATION 7

The best response to this station is the ability to combine appropriate medical information with a demonstration that you are able to break bad news sensitively and honestly. At least one of the communication stations will involve breaking bad news in some form and you should be skilled at this.

These tips for ‘breaking bad news’ should be very familiar to you:

• Establish what the patient knows

• Give information clearly and simply

• Use active listening – pauses, ‘Umm’, ‘yes’, etc.

For this consultation we would include:

A possible consultation may go in the following way:

SWEAT TESTS

Techniques

Technique involves quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis. Two discs are placed on to cleaned skin a few inches apart and an electric current is passed between them. The sweat produced is collected on a paper disc or a macroduct. It takes up to 30 minutes to collect enough sweat (100 mg of sweat is needed). The sodium and chloride are measured in the lab.

COMMENTS ON STATION 8

Here is a possible outline for this conversation:

• Introduce yourself and confirm the name of parent.

• Ask if they wish to have a friend/relative present.

• Try to make the suggestion that you have a nurse with you in the room (they will be imaginary).

• Say that you will not be interrupted during the consultation.

• Offer the opportunity for them to ask questions at any time.

• Recap briefly on James’s progress to date on the unit and reiterate how well he is now doing with feeding and growing.

• Ask what his mother understands about the discharge arrangements.

• Introduce the idea of discharge a day early and why this has become necessary.

• Review the mother’s concerns around discharge and home support network.

• Decide whether discharge that day is possible.

• Review general follow-up, immunisations and sources of help.

This station re-emphasises the importance of seeing new referrals in general paediatric outpatient clinics. You must have a scheme for taking a thorough history without missing important points specific to seizures.

When taking a history of a first fit you must include:

• Birth history (any neonatal fits)

• Development (especially delay in first 2 years of life)

• Did the child have febrile convulsions?

• Any current medical therapy?

• Any history suggestive of a cardiac cause?

• Description of convulsion, ideally from an eye-witness account:

| Seizure | Features |

|---|---|

| Simple partial | Any part of body May spread to become generalised Often secondary to structural defect Focal spikes or slow wave in affected area |

| Benign partial (Rolandic) EEG: centrotemporal spikes |

Partial, which may progress to generalised Often commences in face and tongue (parents hear gargling noise from bedroom) Often nocturnal or early morning Remits in adolescence |

| Myoclonic – akinetic | Violent contractions of muscle groups. May throw patients to the side Minimal or no loss of consciousness Usually evidence/history of brain neurone damage Lennox-Gastaut if associated with mental retardation |

| Juvenile myoclonic EEG: 4–7 Hz spike wave activity |

Early-morning myoclonic jerks (typically of head and neck) Associated with generalised tonic-clonic seizures |

| Absence EEG: three-per-second spike wave activity |

Vacant episodes up to 10 seconds ‘Automatisms’ of face No aura or post-ictal confusion |

| Generalised tonic-clonic EEG: bilaterally synchronous multiple high-voltage spikes |

Loss of consciousness Often preceded by aura or cry May have bladder incontinence or tongue biting |

| Temporal lobe | Clinical features similar to absence seizures (staring, odd facial expressions and fidgeting hand movements) However, may have aura, last longer (30–60 seconds) and autonomic disturbance |

Management may include medical treatment but more importantly a thorough explanation of acute management of the seizure (if only to place the child in the recovery position).

• A thorough neurological examination including fundoscopy

• Blood glucose with every prolonged fit which presents to hospital

Units differ on the initial blood tests and investigations required but after two or more afebrile convulsions consider:

• Full blood count, urea and electrolytes, calcium, magnesium

• ECG and CXR if evidence of cardiac cause

• Explanation of fits and emergency first aid treatment (if not offered at initial presentation)

• UV (Wood’s) light to look for ash leaf depigmentation (tuberous sclerois).

Side effects of most anti-epileptic medication:

Toxic effects include ataxia, confusion, dysarthria and nystagmus.

An unexplained rash should prompt medical review and cessation of medication.