Chronic renal failure

Consequences of CRF

Potassium metabolism

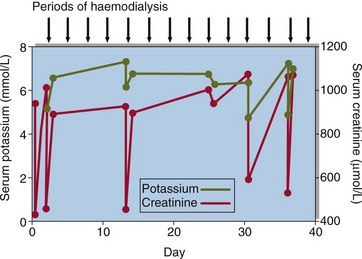

Hyperkalaemia is a feature of advanced CRF and poses a threat to life (Fig 19.1). The ability to excrete potassium decreases as the GFR falls, but hyperkalaemia may not be a major problem in CRF until the GFR falls to very low levels. Then, a sudden deterioration of renal function may precipitate a rapid rise in serum potassium concentration. An unexpectedly high serum potassium concentration in an outpatient should always be investigated with urgency.

Calcium and phosphate metabolism

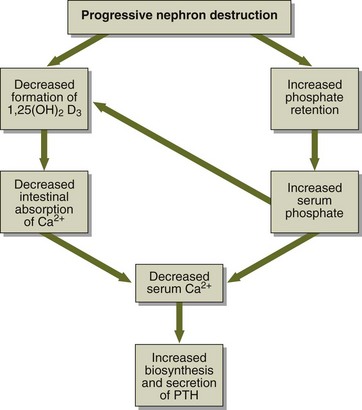

The ability of the renal cells to make 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol falls as the renal tubular damage progresses. Calcium absorption is reduced and there is a tendency towards hypocalcaemia. Phosphate retention, along with low calcium, induces a rise in parathyroid hormone (PTH), and the latter may have adverse effects on bone if this is allowed to continue (renal osteodystrophy; Fig 19.2).

Clinical features

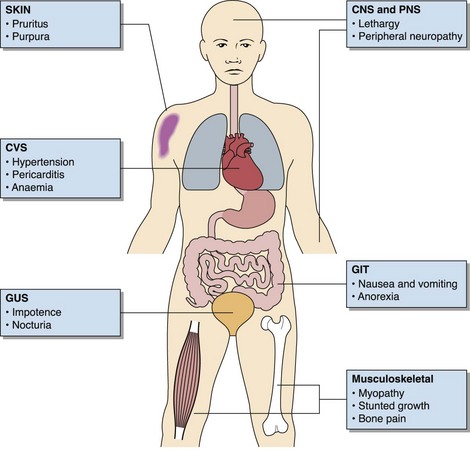

These are illustrated in Figure 19.3. Early in chronic renal failure the normal reduction in urine formation when the patient is recumbent and asleep is lost. Patients who do not experience daytime polyuria may nevertheless have nocturia as their presenting symptom.

Management

Water and sodium intake should be carefully matched to the losses. Dietary sodium restriction and diuretics may be required to prevent sodium overload.

Water and sodium intake should be carefully matched to the losses. Dietary sodium restriction and diuretics may be required to prevent sodium overload.

Hyperkalaemia may be controlled by oral ion-exchange resins (Resonium A).

Hyperkalaemia may be controlled by oral ion-exchange resins (Resonium A).

Hyperphosphataemia may be controlled by oral aluminium or magnesium salts, which act by sequestering ingested phosphate in the gut.

Hyperphosphataemia may be controlled by oral aluminium or magnesium salts, which act by sequestering ingested phosphate in the gut.

The administration of hydroxylated vitamin D metabolites may prevent the development of secondary hyperparathyroidism. There is a risk of hypercalcaemia with this treatment.

The administration of hydroxylated vitamin D metabolites may prevent the development of secondary hyperparathyroidism. There is a risk of hypercalcaemia with this treatment.

Dietary restriction of protein, to reduce the formation of nitrogenous waste products, may give symptomatic improvement. A negative nitrogen balance should, however, be avoided.

Dietary restriction of protein, to reduce the formation of nitrogenous waste products, may give symptomatic improvement. A negative nitrogen balance should, however, be avoided.