Chronic pancreatitis

Definition

Ammann et al. suggested that acute pancreatitis and chronic alcoholic pancreatitis are different stages of the same disease.1,2 Chronic pancreatitis represents the persistent damage after episodes of severe acute pancreatitis.3,4

The classification of CP as an separate disease was described in 1946 by Comfort et al.5 Since then, different classifications of CP have been presented. According to the Marseille Classification, CP is characterised by histological changes, persisting after the aetiologic agent has been removed.6 The Cambridge Classification (1983) defined CP as an ongoing inflammatory disease characterised by irreversible structural changes associated with abdominal pain and permanent loss of function.

Recently, a new classification of CP has been suggested. Probable CP is characterised by a typical history and one or more of the following criteria: recurrent or persistent pseudocysts, ductal alterations, endocrine insufficiency (abnormal glucose tolerance test) or pathological secretin test. Definite CP is characterised by a typical history and at least one of the following criteria: typical histology from an adequate surgical specimen, moderate or marked ductal alterations, pancreatic calcification, marked exocrine insufficiency defined as steatorrhea, normalised or markedly reduced by enzyme substitution.7

Aetiology

Chronic pancreatitis is a highly complex process that begins with episodes of acute pancreatitis and progresses to end-stage fibrosis at different rates in different people due to different mechanisms. The most frequent causes are excess alcohol consumption (70–90%),9 cholelithiasis, autoimmune or individual genetic predisposition and anatomical variants such as pancreas divisum (Box 14.1).

Clinical course

The inflammation leads to progressive and irreversible loss of functional parenchyma and replacement with fibrotic tissue. The ductal system displays strictures of the bile duct, and duodenal stenosis10 or the formation of pancreatic pseudocysts. Furthermore, CP can result in intraductal or parenchymal calcifications of the pancreas.

The natural course is that most patients with long-standing CP will become pain free due to a progressive ‘burning out’ of the organ.12,13 Episodes of pain may occur less frequently, whereas endocrine and exocrine insufficiency commonly worsens. The pancreatic parenchyma is irreversibly converted to fibrous tissue with associated diabetes and steatorrhoea.14

At the time of onset of CP, 8% of patients have at least a moderate degree of endocrine insufficiency, whereas in long-term follow-up approximately 80% have endocrine insufficiency.15,16 Studies have shown that it takes 10–20 years of a progressive inflammatory process to cause exocrine insufficiency by destroying the pancreatic parenchyma.17,18

At least 50–68% of patients with CP need surgery for management of complications or for intractable pain.20 Although spontaneous relief occurs, the effects of chronic pain can have lasting repercussions including depression, opiate addiction, unemployment and social alienation exacerbated by the stigma of alcoholism.

Reduction of alcohol intake does not influence the course of pain in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, but continued alcohol abuse is associated with significantly lower survival rates. Patients that stop drinking may get some improvement in exocrine function.21 Endocrine insufficiency does not alter the course of pain. For the individual patient, the course of the disease is unpredictable.21–23

Pathophysiological findings and pain mechanisms in chronic pancreatitis

The acinar cells are directly damaged by alcohol. A change in microcirculatory perfusion and alterations in epithelial permeability lead to an imbalance in the pancreatic juice, and decreased fluid or bicarbonate secretion. Parenchymal necrosis of the pancreas may induce perilobular fibrosis that leads to intralobular fibrosis, ductal obstruction and periductal inflammation. Altered amounts of lithostatin in the pancreatic juice can lead to formation of protein plugs and stones in ducts and ductules.24

Histomorphologically different forms of CP can be distinguished.

Calcifying CP

The most common form (calcifying CP) is characterised by recurrent bouts of acute pancreatitis with abdominal pain and development of intraductal calculi, protein plugs and parenchyma calcifications. These alterations of various degrees in different stages of the disease lead to pancreatic duct stenosis and consecutively to prestenotic duct dilatation. Additionally, epithelial alterations, inflammatory periductal infiltrations, parenchymal atrophy, necrosis and fibrosis can be found.25

Obstructive CP is often painless and caused by blockage of the main pancreatic duct due to tumour or an inflammatory process (post-acute pancreatitis) that leads to atrophy of the pancreatic tissue and prestenotic duct dilatation. No alteration of the ductal epithelium is found.26 Pancreatic duct stones are uncommon. Periductal fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration are mainly found around the larger ducts and in the pancreatic head. Diffuse fibrotic changes occur throughout the organ without lobular topography. Pancreatic main-duct stenosis may be caused by papillary stenosis (tumour) or inflammation, duodenal diverticula, pancreatic tumours, congenital or acquired duct abnormalities (pancreas divisum), or rarely by traumatic pancreatic duct injuries. Small-duct pancreatitis is an extremely rare form of CP that is defined as main duct diameter ≤ 3 mm, with fibrous and inflammatory tissue.27

Autoimmune pancreatitis

Autoimmune pancreatitis is characterised by the absence of typical risk factors for developing CP or hereditary factors. In the past this subtype was named primary inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas, non-alcoholic duct destructive pancreatitis or lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis.28–30 The term autoimmune pancreatitis was introduced by Yoshida et al. in 1995.31 Autoimmune pancreatitis can present with a focal event or with multiple lesions. Pseudocysts and caliculi are rarely found. Four histological features are characteristic of autoimmune pancreatitis. Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells (often with high levels of IgG4), macrophages, neutrophils and eosinophils result in an intestinal fibrosis.32 Additionally, periductal inflammation and periphlebitis can lead to luminal strictures or obliterative venulitis, respectively. Obstructive jaundice is caused by an effect on the common bile duct that may extend to the gallbladder and biliary tree. An increased level of IgG4 is a sensitive marker.33 Autoimmune pancreatitis is associated with other autoimmune disorders such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Sjörgren’s syndrome, lymphocytic thyroiditis and primary biliary cirrhosis.34

Hereditary CP

Hereditary chronic pancreatitis (HCP) is a rare form with an incidence of approximately 3.5–10 per 100 000 inhabitants.35 The morphological findings in HCP are irregular sclerosis with focal, segmental or diffuse destruction of the parenchyma. Different mutations have been detected to be associated with HCP, most commonly R122H, an N291 mutation of the PRSS1 gene, and mutations of the CFTR and SPINK1 genes.36 The risk of developing pancreatic cancer is increased in HCP with PRSS1 mutation as compared with the normal population and chronic alcoholic pancreatitis.

Pathogenesis of pain in chronic pancreatitis

In the initial stage of the disease the pain is intermittent and recurrent; later it persists. Painless pancreatitis is found rarely in alcohol-induced pancreatitis (< 10%), while pain-free periods are seen in late-onset idiopathic pancreatitis.37

Ebbehoj et al. found a significantly higher pancreatic tissue pressure in patients who had painful CP compared with pain-free controls. These findings are interesting but have not been reproduced by other investigators. The reason for increased pressure can be due to postinflammatory scarring of the pancreatic (main and side) ducts, pancreatic duct stones or stricture or haemosuccus pancreaticus that leads to obstruction. Other reasons are pancreatic abscess, ascites, bile duct stenosis or duodenal stenosis. Patients with a reduced intraductal pressure had better pain relief compared to patients with higher intraductal pressure.38 The assessment of pain is very difficult. Most trials in CP use classifications for description of pre- and postoperative pain or outcome such as excellent (no pain), good (better), fair (nil) and poor (worse); therefore, no comparison between different trials is possible. Pain relief is more common in patients that quit drinking. The underlying mechanism for pain in CP is poorly understood. Different concepts have been hypothesised, but none of them can completely explain the pain in this disease.

It is also likely that an individual’s genetics plays a role in the overall pain experience. Genetic polymorphisms have been associated with disparate postoperative pain sensation and response to narcotics. Unfortunately, examination of candidate gene polymorphisms in visceral pain syndromes has been less convincing and clear evidence is lacking (Box 14.2).

Preoperative assessment and investigations

Imaging studies

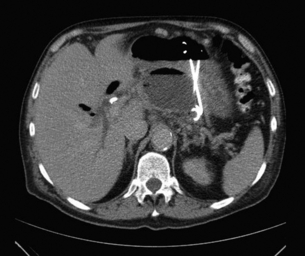

Abdominal ultrasound is an effective method that may help to establish the diagnosis. The use of endoscopic ultrasound is more sensitive and specific. Many patients undergo multiple endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures for diagnosis and therapeutic interventions. The gold standard in diagnosis of CP and for the planning of surgical therapy is contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI offers the additional possibility to evaluate the ductal system by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). The advantage of CT is the better visualisation of parenchymal calcifications. Positron emission tomography (PET) may be helpful to differentiate between CP and pancreatic cancer (Box 14.3).

Treatment

Conservative therapy

The basis of adequate management of CP includes reduction of risk factors, replacement therapy for exocrine and endocrine insufficiency and nutritional supplementation, as well as pain therapy. Medical therapies such as dietary alterations, analgesics (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol, prednisolone, dextropropoxiphene, tricylic antidepressives and in the late stages opioids), oral enzyme supplements and somatostatin analogues may improve symptoms. An important aspect in the treatment of CP patients is a multidisciplinary approach. Alternative therapies such as psychiatric or psychological input, transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation, acupuncture, intrathecal pumps for opioids and spinal cord stimulation may be beneficial as adjunctive treatment (Box 14.4).

Endoscopic and interventional treatment

Endoscopy

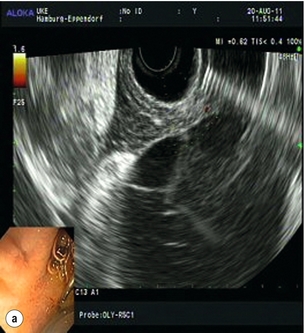

Different endoscopic procedures have been used in the treatment of CP, including sphincterotomy, endoscopic stone extraction (in some trials combined with extracorporal shockwave lithotripsy) and stenting of the pancreatic duct (Fig. 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Endoscopic retrograde pancreatogram and stenting in a patient with chronic pancreatitis.

Endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy in CP is technically challenging. Indications are sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or papillary stenosis/stricture. Another indication is to gain better access to the pancreatic duct for dilatation, transpapillary drainage and stenting (Fig. 14.2). Endoscopic stenting with regular changes resulted in complete pain relief in 45–95% of patients. Early complications (pancreatitis, cholangitis) occurred in 10–15% and late complications (strictures, ductal changes) in 10–30% of patients,39,40 but initial pain relief was 89%. In a further trial, pain control was achieved following stenting in 70% of patients after 12 months’ follow-up and in 62% of patients after 27 months’ follow-up, with an overall morbidity rate of 25%.

Surgical therapy, timing and indications

Two randomised controlled trials have demonstrated the superiority of surgical versus endoscopic therapy in primary success rate, pain relief42,43 and quality of life. The results show that, in patients with advanced calcifying CP and symptomatic pancreatic duct obstruction, surgery is more effective than endoscopy. Surgery was not only more effective but it also required fewer interventions. For most of the surgically treated patients a single operation resulted in immediate and permanent pain relief. Therefore the timing of the intervention should take these facts into consideration.41–45

Nealon and Thompson concluded in their study that early operative drainage should be performed before the gland is functionally and morphologically irreversibly damaged.46 They suggested that patients with obstructive CP-related dilation or obstruction of the pancreatic duct and with biliary pancreatitis should undergo early surgical treatment before nutritional or metabolic disorders occur.

Surgical techniques

Selection of the surgical intervention

Concern about underlying malignancy should be ruled out by frozen section analysis, as differentiating an inflammatory mass from a malignant tumour preoperatively may be challenging. It must be emphasised that in approximately 10% of patients, the initial diagnosis of a pancreatic carcinoma is based on the histological specimen at time of operation.47,48

Simple drainage procedures that represent the other end of the scale aim to drain a dilated pancreatic duct. The indication is ductal ectasia and suspicion of intraductal hypertension without enlargement of the pancreatic head. Whether such simple drainage procedures are combined with a limited or subtotal resection of the pancreatic head depends on the presence or absence of inflammatory enlargement.49

Coffey and Link were the first to describe ductal drainage procedures by opening the main pancreatic duct. Subsequently, DuVal and Zollinger independently performed decompression of the main pancreatic duct by resection of the pancreatic tail and retrograde drainage of the pancreatic duct via a terminoterminal or terminolateral pancreatico-jejunostomy. A further operation is decompression of the main pancreatic duct with resection of the pancreatic tail, splenectomy and longitudinal laterolateral pancreatico-jejunostomy, as described by Puestow and Gillesby. Partington and Rochelle reported a spleen-preserving longitudinal pancreatico-jejunostomy without pancreatic tail resection.50

Pancreatico-duodenectomy

The extent of resection in the Kausch–Whipple procedure includes pancreatic head resection with the duodenum and distal third of the stomach, or it can be modified as a pylorus-preserving pancreatico-duodenectomy (Longmire/Traverso). It offers improvement of the quality of life and pain relief in short- and long-term follow-up in about 90% of patients. The major disadvantage of pancreatico-duodenectomy is the sacrifice of surrounding non-diseased organs with loss of natural bowel continuity. Furthermore, pancreatic exocrine and endocrine function is significantly reduced. Comparing the classic Whipple procedure with the pylorus-preserving pancreatico-duodenectomy, a significantly higher rate of pain and nausea and lower quality of life have been reported.51 Nowadays the procedures can be performed with low mortality (0–5%) in experienced centres, but morbidity rates of 20–40% remain high.52,53

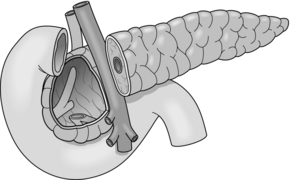

Beger procedure

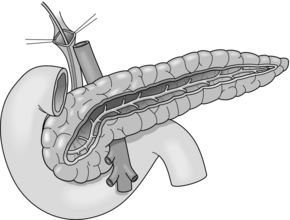

Beger and colleagues introduced the first duodenum-preserving resection of the pancreatic head as an organ-sparing procedure. This method consists of a subtotal resection of the pancreatic head after transection of the pancreas above the portal vein (Fig. 14.3). The pancreas is drained by an end-to-end or end-to-side pancreatico-jejunostomy using a Roux-en-Y loop.

An advantage of this procedure is that physiological gastroduodenal passage and common bile duct continuity are preserved.54,55 The mortality rate in experienced centres is low (0–3%), with morbidity rates of 15–32% and the procedure provides long-term pain relief in 75–95% of patients.56

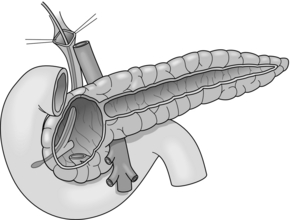

Frey procedure

In 1985, Frey and colleagues developed a modification of the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR). This combined a longitudinal pancreatico-jejunostomy of the body and tail of the pancreas (Partington–Rochelle procedure) with a limited duodenum-preserving excision of the pancreatic head. In contrast to the Beger procedure, the pancreas is not divided over the superior mesenteric portal vein (Fig. 14.4) and reconstruction can be performed with one single anastomosis. The head of the pancreas is cored out, leaving a small cuff along the duodenal wall. Drainage of the cavity of the pancreatic head and the opened main duct of the body and tail is performed with a longitudinal pancreatico-jejunostomy using a Roux-en-Y loop. The Frey procedure can be performed with low mortality (< 1%) and acceptable morbidity (9–39%). In a prospective trial, 56% of patients were pain free and 32% had substantial pain relief. Exocrine and endocrine pancreatic functions are preserved and the procedure can be combined with procedures to treat complications of adjacent organs such as common bile duct stenosis, duodenal stenosis and internal pancreatic fistulas.57

Berne procedure

The Berne variation derives from a similar idea and combines the advantages of the Frey and Beger procedures.58 This operation avoids the delicate division of the pancreatic neck anterior to the portal vein as in Beger’s procedure, but compared to a Frey procedure, the extent of pancreatic resection is much greater and the common bile duct is decompressed. No longitudinal drainage of the pancreatic duct, as described by Frey and Izbicki, is performed. In patients with common bile duct obstruction, a longitudinal opening in the cavity of the pancreatic head is performed for bile drainage. The Berne procedure has been shown to be feasible, effective and safe with a mortality of 0–1% and a morbidity rate of 20–23%.59

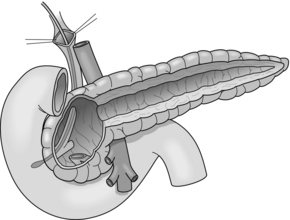

Hamburg procedure

The Hamburg procedure is a further established modification of a DPPHR that combines aspects of the Beger and Frey procedures (Fig. 14.5). Subtotal excision of the pancreatic head including the uncinate process is performed. The extent of the cephalic decompression is comparable to the Beger procedure but avoids transection of the gland over the superior mesenteric portal vein as in a Frey procedure.

Drainage of the body and tail of the organ is achieved by excision of the ventral aspect of the pancreas into the pancreatic duct followed by longitudinal pancreatico-jejunostomy of the body and tail of the pancreas, which is comparable to the Partington–Rochelle procedure. The major advantage of this technique is that the extent of the resection can be customised to the individual morphology of the pancreas. It has been established as an effective and safe procedure, especially in patients with the sclerosing form of pancreatitis or extensive parenchymatous calcifications.60 The V-shaped excision creates a trough-like new duct system; the underlying principle is the drainage of second- and third-order pancreatic duct side branches.

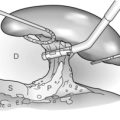

V-shaped excision

The sclerosing entity of CP, e.g. small-duct disease, is characterised by a non-dilated Wirsung duct with narrowing or even ‘pseudo-vanishing’. For this disease, the authors suggest a longitudinal V-shaped excision of the ventral aspect of the pancreas combined with a longitudinal pancreatico-jejunostomy (Fig. 14.6). If this condition is accompanied by an enlarged pancreatic head, pancreatic head resection should be performed.

Selection of the procedure

In summary, duodenum-preserving resection of the pancreatic head is a less invasive technique compared to pancreatico-duodenectomy, with benefits especially concerning pain relief and improvement of quality of life during the first 2 years postoperatively. The comparable results of the different technique of duodenum preserving pancreatic head resections (Beger, Frey, Hamburg and Berne) are not surprising considering that all procedures involve the removal of a portion of the pancreatic head and effectively decompress the main pancreatic duct.61 The major difference is the transection of the pancreatic neck in the Beger procedure and the additional longitudinal drainage of the pancreatic duct in the body and tail of the organ in the Frey and Hamburg procedures.

Salvage procedures

In patients that have previously undergone DPPHR or partial pancreatico-duodenectomy with recurrence of the CP in the body or tail, a V-shaped drainage procedure is indicated (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1

| Indications | Pain |

| Complications | |

| Unsuccessful other treatment | |

| Suspicion of malignancy | |

| Surgical techniques | |

| Pure drainage | |

| Cystojejunostomy | Isolated pseudocyst |

| Pancreatico-jejunostomy | |

| Partington–Rochelle procedure | Ductal dilation (>7 mm) Without inflammatory mass |

| Resection procedures | |

| Pancreatic head resection | Inflammatory mass in the head of pancreas |

| PD and ppPD | Suspicion of malignancy |

| Irreversible duodenal stenosis | |

| DPPHR | |

| Beger | Inflammatory mass in head |

| Bern | Less difficult than Beger |

| Frey | Ductal obstruction in head and tail |

| Hamburg | Combines aspects of Beger and Frey |

| Sclerosing pancreatitis | |

| Extensive parenchymatous calcification | |

| V-shaped excision | Small-duct disease (<3 mm) |

| Left resection | Isolated CP in tail (rare) |

| Pseudoaneurysms | |

| Segmental resection | Isolated ductal stenosis in body |

| Total pancreatectomy | Changes in entire pancreas (rare) |

Complications of chronic pancreatitis

Pancreatic ascites (Fig. 14.7) is found in approximately 4% of patients with CP and in 6–14% of those with a pancreatic pseudocyst (Fig. 14.8). It is defined as massive accumulation of pancreatic fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The amylase level in the ascitic fluid is typically above 1000 IU/L. ERCP should be performed to localise the site of leakage and to perform endoscopic pancreatic duct stenting. Additional treatment with somatostatin or octreotide together with diuretics and repeated paracentesis may be beneficial for some patients. In patients with persistent or recurrent accumulation of ascites and/or sudden deterioration of clinical status, surgery may be indicated.

The treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts should consider several aspects. Within 6 weeks a spontaneous resolution may occur in 40% of patients, whereas the pseudocyst-related complication rate, especially haemorrhage and infection (Fig. 14.9), is 20%. After 6 weeks, the rate of spontaneous remission is 4% and the complication rate increases to 56%. Therefore, intervention should be delayed for 6 weeks after diagnosis in patients with an uncomplicated pseudocyst. However, in patients with haemorrhage, abscess or infection, immediate intervention is mandatory. Surgery is only indicated if internal (transgastric) or CT-guided drainage fails.

Pancreatico-pleural fistulas result from a disruption of the pancreatic duct or leakage from a pseudocyst. They are rare, but associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Three main types of thoracic manifestations are mediastinal pseudocyst formation, pancreatico-pleural fistula and pancreatico-bronchial fistula. Once a pancreatico-pleural fistula is suspected, the concentration of amylase in the pleural effusion should be measured. Conservative treatment has an efficacy of 30–60%, a recurrence rate of 15% and a mortality rate of 12%.62 If conservative therapy fails, endoscopic sphincterotomy or stenting and surgery should be considered, aiming to reduce the intraductal hypertension as this inhibits the spontaneous closure of fistula.

Extrahepatic portal hypertension is a less common complication of CP. It may be confined to either the superior mesenteric or splenic venous branch or may involve the whole spleno-mesenterico-portal axis.63 It is defined as extrahepatic hypertension of the portal venous system in the absence of liver cirrhosis. The pathogenesis of extrahepatic portal hypertension in CP may include several factors. The inflammatory process is capable of causing initial damage to vascular walls and generating venous spasm, venous stasis and thrombosis.

References

1. Ammann, R.W., Akovbiantz, A., Largiader, F., et al, Course and outcome of chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal study of a mixed medical-surgical series of 245 patients. Gastroenterology. 1984;86(5, Pt 1):820–828. 6706066

2. Strate, T., Yekebas, E., Knoefel, W.T., et al, Pathogenesis and the natural course of chronic pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(9):929–934. 12352211

3. Kloppel, G., Maillet, B., Pathology of acute and chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1993;8(6):659–670. 8255882

4. Kloppel, G., Maillet, B., The morphological basis for the evolution of acute pancreatitis into chronic pancreatitis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992;420(1):1–4. 1539444

5. Kloppel, G., Chronic pancreatitis, pseudotumors and other tumor-like lesions. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(Suppl. 1):S113–S131. 17486047

6. Banks, P.A., Classification and diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(Suppl. 17):148–151. 17238045

7. Ammann, R.W., Diagnosis and management of chronic pancreatitis: current knowledge. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(11–12):166–174. 16633964 This paper reviews the literature on CP. Based on experience, some of the discussed features such as aetiology and staging may help to predict in a given patient what is the risk for having a good or bad outcome without or with a surgical (or endoscopic) intervention.

8. Lohr, J.M., Medical treatment of pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7(4):533–544. 17428173

9. Mayerle, J., Lerch, M.M., Is it necessary to distinguish between alcoholic and nonalcoholic chronic pancreatitis? J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(Suppl. 17):127–130. 17238041

10. Pessaux, P., Varma, D., Arnaud, J.P., Pancreaticoduodenectomy: superior mesenteric artery first approach. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(4):607–611. 16627229

11. Knoefel, W.T., Eisenberger, C.F., Strate, T., et al, Optimizing surgical therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2(4):379–384. 12138226

12. Ammann, R.W., Alcoholic pancreatitis with special reference to clinical course, diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 1984;73(18):573–577. 6203159

13. Ammann, R.W., Akovbiantz, A., Largiader, F., Pain relief in chronic pancreatitis with and without surgery. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(3):746–747. 6745625

14. Chari, S.T., Chronic pancreatitis: classification, relationship to acute pancreatitis, and early diagnosis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(Suppl. 17):58–59. 17238029

15. Malka, D., Hammel, P., Sauvanet, A., et al, Risk factors for diabetes mellitus in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(5):1324–1332. 11054391

16. Malka, D., Vasseur, S., Bodeker, H., et al, Tumor necrosis factor alpha triggers antiapoptotic mechanisms in rat pancreatic cells through pancreatitis-associated protein I activation. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(3):816–828. 10982776

17. Lankisch, P.G., Lohr-Happe, A., Otto, J., et al, Natural course in chronic pancreatitis. Pain, exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency and prognosis of the disease. Digestion. 1993;54(3):148–155. 8359556

18. Lankisch, P.G., Enzyme treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in chronic pancreatitis. Digestion. 1993;54(Suppl. 2):21–29. 8224569

19. Layer, P., Yamamoto, H., Kalthoff, L., et al, The different courses of early- and late-onset idiopathic and alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(5):1481–1487. 7926511

20. Parc, R., Frileux, P., Tiret, E., et al, Acute necroticohemorrhagic pancreatitis. Why, when and how to drain? Apropos of 106 cases. Chirurgie. 1989;115(9):651–655. 2642154

21. Lankisch, M.R., Imoto, M., Layer, P., et al, The effect of small amounts of alcohol on the clinical course of chronic pancreatitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(3):242–251. 11243270

22. Lankisch, P.G., Natural course of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2001;1(1):3–14. 12120264

23. Lankisch, P.G., Assmus, C., Lehnick, D., et al, Acute pancreatitis: does gender matter? Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46(11):2470–2474. 11713955

24. Sarles, H., Epidemiology and physiopathology of chronic pancreatitis and the role of the pancreatic stone protein. Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;13(3):895–912. 6386244

25. Kloppel, G., Pathology of chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic pain. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156(4):261–265. 2349844

26. Lehnert, P., Etiology and pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis. Internist (Berl). 1979;20(7):321–330. 113358

27. Yekebas, E.F., Bogoevski, D., Honarpisheh, H., et al, Long-term follow-up in small duct chronic pancreatitis: a plea for extended drainage by “V-shaped excision” of the anterior aspect of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):940–946. 17122619

28. Ectors, N., Maillet, B., Aerts, R., et al, Non-alcoholic duct destructive chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1997;41(2):263–268. 9301509

29. Strate, T., Taherpour, Z., Bloechle, C., et al, Long-term follow-up of a randomized trial comparing the Beger and Frey procedures for patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2005;241(4):591–598. 15798460

30. Strate, T., Mann, O., Kleinhans, H., et al, Microcirculatory function and tissue damage is improved after therapeutic injection of bovine hemoglobin in severe acute rodent pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30(3):254–259. 15782104

31. Yoshida, K., Toki, F., Takeuchi, T., et al, Chronic pancreatitis caused by an autoimmune abnormality. Proposal of the concept of autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40(7):1561–1568. 7628283

32. Toomey, D.P., Swan, N., Torreggiani, W., et al, Autoimmune pancreatitis: medical and surgical management. JOP. 2007;8(3):335–343. 17495364

33. Choi, E.K., Kim, M.H., Lee, T.Y., et al, The sensitivity and specificity of serum immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin G4 levels in the diagnosis of autoimmune chronic pancreatitis: Korean experience. Pancreas. 2007;35(2):156–161. 17632322

34. Agrawal, S., Daruwala, C., Khurana, J., Distinguishing autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreaticobiliary cancers: current strategy. Ann Surg. 2012;255(2):248–258. 21997803

35. Barkin, J.S., Fayne, S.D., Chronic pancreatitis: update 1986. Mt Sinai J Med. 1986;53(5):404–408. 3489182

36. Whitcomb, D.C., Gorry, M.C., Preston, R.A., et al, Hereditary pancreatitis is caused by a mutation in the cationic trypsinogen gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14(2):141–145. 8841182

37. Fasanella, K.E., Davis, B., Lyons, J., et al, Pain in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36(2):335–364 ix. 17533083

38. Ebbehoj, N., Borly, L., Bulow, J., et al, Pancreatic tissue fluid pressure in chronic pancreatitis. Relation to pain, morphology, and function. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25(10):1046–1051. 2263877

39. Buscaglia, J.M., Kalloo, A.N., Pancreatic sphincterotomy: technique, indications, and complications. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(30):4064–4071. 17696223

40. Buscaglia, J.M., Kalloo, A.N., Jagannath, S.B., Endoscopic versus surgical treatment for chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(20):2102–2104. 17511055

41. Liao, Q., Wu, W.W., Li, B.L., et al, Surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1(3):462–464. 14607728

42. Dite, P., Ruzicka, M., Zboril, V., Novotny, I., A prospective, randomized trial comparing endoscopic and surgical therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Endosc. 2003;35(7) July:553–558. 12822088

43. Cahen, D.L., Gouma, D.J., Nio, Y., Rauws, E.A., Boermeester, M.A., Busch, O.R., et al, Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(7) February 15:676–684. 17301298

44. Cahen, D.L., Gouma, D.J., Laramee, P., et al, Long-term outcomes of endoscopic vs surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1690–1695. 21843494

45. Strobel, O., Buchler, M.W., Werner, J., Surgical therapy of chronic pancreatitis: indications, techniques and results. Int J Surg. 2009;7(4):305–312. 19501199

46. Nealon, W.H., Thompson, J.C., Progressive loss of pancreatic function in chronic pancreatitis is delayed by main pancreatic duct decompression. A longitudinal prospective analysis of the modified Puestow procedure. Ann Surg. 1993;217(5):458–466. 8489308

47. Ihse, I., Borch, K., Larsson, J., Chronic pancreatitis: results of operations for relief of pain. World J Surg. 1990;14(1):53–58. 2407038

48. Ihse, I., Gasslander, T., Surgical treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis: the role of pancreaticojejunostomy. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156(4):299–301. 2349849

49. Buchler, M., Uhl, W., Beger, H.G., Surgical strategies in acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40(6):563–568. 8119641

50. Partington, P.F., Rochelle, R.E., Modified Puestow procedure for retrograde drainage of the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg 1960; 152:1037–1043. 13733040

51. Mobius, C., Max, D., Uhlmann, D., et al, Five-year follow-up of a prospective non-randomised study comparing duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection with classic Whipple procedure in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392(3):359–364. 17375317

52. Warshaw, A.L., Pain in chronic pancreatitis. Patients, patience, and the impatient surgeon. Gastroenterology. 1984;86(5, Pt 1):987–989. 6706079

53. Strate, T., Bachmann, K., Busch, P., et al, Resection vs drainage in treatment of chronic pancreatitis: long-term results of a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1406–1411. 18471517

54. Izbicki, J.R., Bloechle, C., Knoefel, W.T., et al, Complications of adjacent organs in chronic pancreatitis managed by duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 1994;81(9):1351–1355. 7953411

55. Frey, C.F., Amikura, K., Local resection of the head of the pancreas combined with longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy in the management of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1994;220(4):492–504. 7524454

56. Buchler, M.W., Friess, H., Muller, M.W., et al, Duodenum preserving resection of the head of the pancreas: a new standard operation in chronic pancreatitis. Langenbecks Arch Chir Suppl Kongressbd 1997; 114:1081–1083. 9574339

57. Beger, H.G., Buchler, M., Bittner, R.R., et al, Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in severe chronic pancreatitis. Early and late results. Ann Surg. 1989;209(3):273–278. 2923514

58. Gloor, B., Friess, H., Uhl, W., et al, A modified technique of the Beger and Frey procedure in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2001;18(1):21–25. 11244255

59. Koninger, J., Seiler, C.M., Sauerland, S., et al, Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection – a randomized controlled trial comparing the original Beger procedure with the Berne modification (ISRCTN No. 50638764). Surgery. 2008;143(4):490–498. 18374046

60. Bachmann, K., Mann, O., Izbicki, J.R., et al, Chronic pancreatitis – a surgeon’s view. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14(11):RA198–RA205. 18971885

61. Diener, M.K., Rahbari, N.N., Fischer, L., et al, Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection versus pancreatoduodenectomy for surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2008;247(6):950–961. 18520222

62. Kaman, L., Behera, A., Singh, R., et al, Internal pancreatic fistulas with pancreatic ascites and pancreatic pleural effusions: recognition and management. Aust N Z J Surg. 2001;71(4):221–225. 11355730

63. Izbicki, J.R., Yekebas, E.F., Strate, T., et al, Extrahepatic portal hypertension in chronic pancreatitis: an old problem revisited. Ann Surg. 2002;236(1):82–89. 12131089