Chapter 12 CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The most common cause of chronic pancreatitis in Western nations is alcohol abuse (Table 12.1).

Alcohol

Alcohol accounts for 70%–90% of all cases of chronic pancreatitis in Western societies. The onset of alcoholic pancreatitis usually occurs in the fourth decade, and the majority of patients are males consuming alcohol in the order of 100–150 g/day (i.e. 10–15 standard drinks/day) in the 5–15 years prior to initial presentation. Typically, the initial clinical presentation of alcohol-mediated pancreatic injury is acute pancreatitis. However, the characteristic histological and radiological features of chronicity (atrophy, fibrosis and calcification) are already evident in a large proportion of these patients on initial presentation.

Cystic fibrosis

There is a correlation between the degree of abnormal CFTR function and severity of cystic fibrosis. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency occurs in approximately 85% of patients with cystic fibrosis due to defective secretory capacity of bicarbonate and digestive enzymes. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic atrophy arises from inspissated protein-rich acinar secretions that obstruct the ducts resulting in cellular destruction and fibrosis.

ASSESSMENT

History and examination

Steatorrhoea and diarrhoea

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency may occur as early as 5–6 years after disease onset. Maldigestion may occasionally occur in the absence of abdominal pain. Steatorrhoea occurs in approximately 30% of patients with chronic pancreatitis, and a history of the passage of ‘oil’ at defecation is virtually pathognomonic of pancreatic steatorrhoea. The degree of steatorrhoea depends on the amount of fat ingested.

Investigations

Pancreatic imaging

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) defines abnormalities of pancreatic ducts in chronic pancreatitis. However, ERCP is invasive and can cause complications including inducing acute pancreatitis, duodenal perforation, sepsis and haemorrhage. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is non-invasive and can demonstrate ductal anatomy with accuracy comparable to that of ERCP.

Pancreatic function tests

Differential diagnosis of chronic upper abdominal pain

Biliary causes

Biliary colic is typically visceral, sudden in onset and localised in the epigastrium. Movement does not aggravate pain. Common bile duct stones may also cause jaundice, cholestasis (pale stools with dark urine) and cholangitis (fever, rigors). Cholecystitis causes a peritoneal type of pain and tenderness localised at the right upper quadrant. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction also presents with recurrent biliary pain.

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

Treatment of pain

Analgesics

Analgesics, including non-steroidal antiinflammatory agents, paracetamol and tramadol, should be tried initially. Non-opioid analgesics, however, are often insufficient in managing pain and patients frequently require preparations that include codeine, dextropropoxyphene, oxycodone or morphine. Long-acting agents are more effective (e.g. transdermal fentanyl). A common dilemma is differentiating between narcotic addiction and pancreatic pain as the major driving force behind the patient’s presentation.

Endoscopic interventional therapies

These procedures have been designed to clear the ducts of calculi (often with the aid of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy), relieve duct obstruction due to strictures (by stenting) or divide the pancreatic duct sphincter, with the rationale that pain from chronic pancreatitis partly originates from raised intraductal and/or interstitial pressure. As yet these procedures have not been subjected to high-quality randomised controlled trials.

COMPLICATIONS OF CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

Pancreatic pseudocyst

Pseudocysts can occur in approximately 25% of patients with chronic pancreatitis. They present with pain, local pressure symptoms caused by mass effect, bleeding or sepsis. Symptomatic longstanding pseudocysts that are greater than 6 cm and with mature walls are usually treated. Drainage of the cyst can be percutaneous, EUS-guided, or surgical (cystogastrostomy, cystoenterostomy).

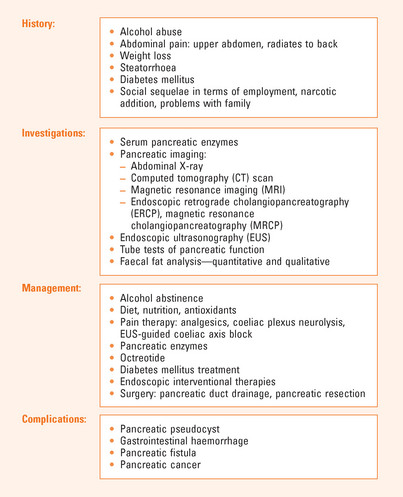

SUMMARY

Up to 50% of patients with chronic pancreatitis develop diabetes mellitus. Pancreatic imaging is a vital part of the investigation of chronic pancreatitis (see Figure 12.1). Tests include abdominal X-ray and ultrasonography to detect calcification. CT scan and MRI can detect pancreatic necrosis and fluid collections. MRCP can demonstrate ductal anatomy. EUS assesses parenchyma and duct and can biopsy suspicious lesions.

Quantitative or qualitative faecal fat analysis may assist in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.

Management focuses on alcohol abstinence, improving nutrition and treatment of pain. Non-opioid analgesics may help, but patients often require narcotic preparations. Exogenous pancreatic enzymes are the cornerstone of therapy.

Endoscopic interventional therapies have been used to clear the ducts of calculi, relieve duct obstruction due to strictures or to divide the pancreatic duct sphincter. Surgery may be indicated to decompress the pancreatic duct and is more effective than endoscopic trans-ampullary drainage.

Ahlgren JD. Epidemiology and risk factors in pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:241-250.

Apte MV, Keogh GW, Wilson JS. Chronic pancreatitis: complications and management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:225-240.

Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Nio Y, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:727-729.

DiMagno MJ, Di Magno EP. Chronic pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21(5):544-554.

Friess H, Beger HG, Sulkowski U, et al. Randomized controlled multicentre study of the prevention of complications by octreotide in patients undergoing surgery for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1270-1273.

Kim KP, Kim MH, Song MH, et al. Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(8):1605-1616.

Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433-1437.

Malfertheimer P, Mayer D, Buchler M, et al. Treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis by inhibition of pancreatic secretion with octreotide. Gut. 1995;36:450-454.

Scolapio JS, Malhi-Chowla N, Ukleja A. Nutrition supplementation in patients with acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1999;28(3):695-707.

Whitcomb DC. The spectrum of complications of hereditary pancreatitis. Is this a model for future gene therapy? Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 1999;28:525-542.