44 Chronic Pain

Chronic Pain in Children

Chronic pain affects a large number of children.1 Back pain has been reported in up to 50% of children by the mid-teens,2 and abdominal pain occurs weekly in up to 17%.3 Other conditions such as headaches, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), fibromyalgia, limb pain, chest pain, and joint pain are common and affect quality of life.4–7

Several chronic medical conditions are strongly associated with pain and blur the boundaries between acute and chronic pain treatment, including sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis,8 epidermolysis bullosa,9 and cancer. These children require frequent hospitalizations, and their pain can be severe. Because the children present with pain in the hospital, treatment often follows the model for acute pain management based on medication use. However, psychosocial factors heavily influence the child’s ability to cope and can improve or worsen the child’s suffering, depending on personal and family factors.10,11 It is appropriate to seek psychology, child life, and physical therapy consultations as part of the therapeutic plan. The ultimate goal for each of these medical conditions is to stabilize the child’s condition and return her or him home. For many, the painful disease and dysfunction continue, and having a long-term plan that is integrated with acute management is vital.

Multidisciplinary Approach

The model of care that appears to work optimally for children with chronic pain is one in which multiple disciplines are involved in developing a coordinated care plan.4,12 In the outpatient setting, there is a pain physician, a psychologist, nurses, and a physical therapist. Sometimes, a neurologist or physiatrist may be involved. Anesthesiologists managing children with chronic pain should make use of these disciplines when recommending a plan of care. Advocating for the involvement of other therapeutic specialties can advance the patient’s care beyond suggesting a regional block or medication.

The Psychologist

Pain is more than just a physical phenomenon. It can cause and be worsened by stress, suffering, family dysfunction, social tension, anxiety, and depression.5,13 Pain can disrupt almost any aspect of the life of the child or family. Family and school problems can worsen a painful condition and dramatically reduce a child’s level of function. The family is always involved in the child’s suffering and should therefore be included in the pain evaluation process.

The Physical Therapist

Physical therapy can benefit many painful conditions (e.g., myofascial pain improves with stretching and range-of-motion exercises) and is the cornerstone of treatment for others (e.g., chronic regional pain syndromes [CRPS]).14 Emphasizing self-reliance and responsibility for their own care is an important aspect of caring for adolescents. However, young children and older ones in pain cannot be expected to work aggressively at home without beginning with a structured program. Parental involvement is especially important for younger children, but the caretakers must be taught to be encouraging and supportive while not making them the child’s taskmasters.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is an effective,15 low-risk, analgesic therapy that is usually provided under the guidance of a physical therapist. TENS is excellent for localized pain. The fact that it is portable, can be used discreetly, and has few side effects makes it attractive for use at school. Because tolerance to TENS can develop with prolonged use, children need to limit use to no longer than 2 hours at a time. They can take a break for an amount of time equal to the TENS use and then restart it.

General Approach to Management

History

A vital part of the chronic pain evaluation process is to look for red flags, which are signs or symptoms that may indicate a serious illness. Some of the red flag signs and symptoms for major pain types can be found in Tables 44-1, 44-2, and 44-3. For example, a child with back pain who also has weak legs and incontinence may have a tethered spinal cord. Headache that is worse in the morning and associated with vomiting suggests increased intracranial pressure. Back pain with loss of ankle jerk suggests compression of the S1 nerve root.

TABLE 44-1 Red Flag Signs and Symptoms for Abdominal Pain

TABLE 44-2 Red Flag Signs and Symptoms for Secondary Headache

TABLE 44-3 Red Flag Signs and Symptoms for Back Pain

A complete pain evaluation comprises further history regarding medications, allergies, family history, and a thorough review of systems. Certain painful conditions, such as migraine headaches,16 fibromyalgia,17 irritable bowel syndrome,18 and sickle cell disease, have a genetic basis. Knowing the family history can assist in making the diagnosis. The child sometimes may model his or her behavior after a family member. For example, if a parent has a “bad back” and is functionally compromised, the child also may complain of back pain. This does not mean the child is faking the complaints but simply patterning the behavioral response to pain after a model that he or she understands. Treatment can include reassurance, cognitive behavioral therapy, and gentle physical therapy to restore the child’s functional ability and help him or her with any underlying issues. Family and social histories can be useful in fashioning a treatment plan in conjunction with the general history, physical examination, and relevant testing.

Chronic Pain Conditions

Any part of the body can hurt, but in practical terms, several diagnostic clusters represent most pediatric pain conditions. The frequency and intensity of the pain can be striking. One study on the 3-month prevalence, characteristics, consequences, and provoking factors of chronic pain described the experience of 749 children and adolescents in one elementary and two secondary schools19: 83% experienced pain during the preceding 3 months. The leading sources of pain were headaches (60.5%, also perceived as most bothersome), abdominal pain (43.3%), extremity pain (33.6%), and back pain (30.2%). Many subjects reported associated sleep problems, restriction in hobbies, and eating problems. School absenteeism reached 48.8% in the population with pain. The use of health care resources by children and adolescents with pain was extensive: 50.9% visited the physician’s office, and 51.5% reported use of pain medication.

Abdominal Pain

Abdominal pain is a major source of distress in children that causes anxiety and invites a large amount of testing. This painful condition, formerly referred to as recurrent abdominal pain, is now described as functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs).20 Specific criteria exist for the major categories so that FGIDs are no longer considered diagnoses of exclusion. The pain is thought to be caused by abnormal interactions between the enteric nervous system and central nervous system.21 Research suggests that peripheral sensitization and abnormal central processing of afferent signals at the level of the central nervous system play roles in the pathophysiology of visceral hyperalgesia—a decreased threshold for pain in response to changes in intraluminal pressure.22 The history and physical examination focus on excluding warning signs and symptoms of underlying disease (see Table 44-1).20,23 The role for testing, endoscopy, and radiographic evaluation is limited.

Multidisciplinary treatment of FGIDs includes medication, psychological interventions, and education, which often need to be ongoing. The most important aspect of the treatment plan is to establish realistic goals, which frequently means return of function rather than complete elimination of pain. Although the literature for treatment is sparse, tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or doxepin have been used effectively for FGID-related pain. Anticonvulsants also are useful because they modify nerve conductivity and transmission. Antacids, antispasmodic agents, smooth muscle relaxants, laxatives, and antidiarrheal agents can be added to address symptoms. Data support the use of peppermint oil capsules in managing irritable bowel syndrome, although gastroesophageal reflux can be a limiting adverse effect.24 Children with functional bowel disorders can have abnormal bowel reactions to physiologic stimuli, noxious stressful stimuli, or psychological stimuli (e.g., parental separation, anxiety). Children benefit from cognitive- behavioral therapy, coping skill development, biofeedback, hypnosis, and relaxation techniques (Table 44-4).25,26

TABLE 44-4 Care Pathway for Abdominal Pain

Behavioral medicine assessment

Review of records, treatments, history, and physical findings

Consultations with pediatrics, surgery, and gastroenterology specialists as indicated by presence of red flags; assessment may include laboratory testing, ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, endoscopy, lactose testing

Medications: tricyclic antidepressants; consider selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; peppermint oil

Behavioral medicine: important and effective to de-medicalize therapy; de-emphasize testing and search for organic diagnoses; redirect focus to treatment and improved function

Physical therapy: not usually involved; trial of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) if abdominal wall origin found

Headache

Headaches can be categorized as primary or secondary. Primary headaches include migraine, tension, cluster, and trigeminal neuralgia headaches. Secondary headaches are those attributable to head and neck traumas; muscle spasms; vascular disorders; nonvascular intracranial disorders; infection; eye, ear, cranium, nose, sinus, and teeth or mouth diseases; homeostatic disturbances; and psychiatric disorders. Headaches represent one of the more poorly tolerated types of chronic pain, with greater medication use than for other types. Of 77 children with long-term headaches who were followed up to 20 years after the initial diagnosis, 27% were headache free, and 66% had improved.27

Migraines (especially migraine without aura) and tension-type headaches are the most common types of pediatric headaches. The prevalence of migraine ranges from 2.7% to 10%. It occurs more frequently in boys than girls between 4 and 7 years of age, and then the prevalence equalizes between 7 and 11 years of age. After 11 years of age, three times more girls than boys have migraines.28,29 Studies are not routinely recommended in the absence of focal neurologic findings. However, the practitioner must be alert to red flag signs and symptoms that warrant imaging and laboratory studies to rule out an underlying condition as a cause of the headaches (see Table 44-2).

There is a genetic component to migraine and chronic tension headaches; 50% to 77% of children with migraines have a positive family history for migraine headaches, especially on the maternal side. The clearest genetic link has been established for familial hemiplegic migraine.16

Treatments for migraine and tension-type headaches overlap greatly. Pharmacologic interventions can be divided in two types. In the first, abortive treatment focuses on stopping the acute headache. In the second, prophylactic therapy is indicated for patients with more than two headaches per month, for children with severe attacks, and for those with frequent headaches unresponsive to medication (Table 44-5).30

TABLE 44-5 Care Pathway for Headaches

Older medications that have been used successfully to prevent headaches in adolescents include amitriptyline and trazodone. These medications tend to make children drowsy and are prescribed 30 to 60 minutes before bedtime each night. Younger children appear to respond well to the antihistamine cyproheptadine. Overall, few evidence-based recommendations can be made; the lack of randomized, controlled pediatric trials precludes an evidence-based recommendation.31 However, the anticonvulsant topiramate is a promising medication for the prevention of migraine headaches.32–34

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Type I and type II CRPS are different only in the presence of a documented nerve injury in type II (formerly called causalgia). Pain is an obligatory feature, often occurring alongside allodynia or hyperalgesia. There must be evidence at some time (not necessarily at the time of diagnosis) of edema, changes in skin blood flow, or abnormal sudomotor activity in the region of pain. There are often features of a motor disorder such as tremor, dystonia, and weakness that sometimes lead to a loss of joint mobility. Nail and hair growth can also be affected. In the past, three distinct stages were described. However, it may be that there are phenotypic subtypes instead of stages.35

From a clinical standpoint, the typical pediatric CRPS patient is older than 10 years of age, Caucasian, female, and very active or a high achiever from an active family, and the child or adolescent presents with lower extremity pain.36 A genetic predisposition is suggested by the clinical observation that CRPS is rare in the African American population. The rarity of CRPS in preadolescent children suggests a developmental aspect to its origin.

It is important to obtain a detailed history of the mechanism of trauma and the signs and symptoms. The examiner should specifically look for pain, allodynia, hyperalgesia, and hyperpathia. Edema and color changes do not have to be present at the time of diagnosis, but there should be a history of such changes in the recent past (Fig. 44-1). A complete neurologic examination includes testing muscle strength, reflexes, sensory responses (e.g., cold, touch, pinprick), capillary refill, temperature, and color differences. The physician should also look for deep tissue hyperalgesia. Occasionally, noninvasive or invasive testing may be helpful, but it is not sensitive or specific. These evaluations may include an electromyogram with nerve conduction velocity (EMG/NCV), quantitative sensory testing (QST), and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing (QSART) to detect small fiber dysfunction; thermography; and bone scans. Sympathetic ganglion blocks are not considered necessary for diagnosis, but they can be part of the therapeutic approach.

The therapeutic goal for CRPS is restoration of function. It may seem simple, but in daily practice, this may represent the biggest challenge for the physician and the child. The therapeutic approach to the child with CRPS is multidisciplinary, with a focus on the psychosocial and physical aspects of the disease (Table 44-6). Education is important, and the information available on the Internet is ubiquitous, although it is often discouraging and not applicable to children with CRPS. No isolated treatment technique has been helpful for this condition. Children and physicians should follow an algorithm and adjust the therapeutic strategy every 4 weeks if the child does not respond satisfactorily to chosen measures.

TABLE 44-6 Care Pathway for Complex Regional Pain Syndromes

Medications: tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin, oxcarbazepine

Behavioral medicine: very important, especially in refractory cases

Physical therapy: activate, range of motion, desensitization, strength training. Structured home program extremely important; may use transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit

The role of interventional therapy in the treatment of CRPS is to alleviate the pain and provide the child with the opportunity to tolerate and advance in physical therapy. Sympathetic nerve blocks are widely used in adults although a systematic review revealed a lack of randomized, controlled trials to confirm the effectiveness of this approach in short-term and long-term pain relief.37 Interventional therapies can be a double-edged sword, representing an easy solution that can demotivate the child from taking an active role in his or her physical therapy. However, pain may be too severe to allow physical therapy and thereby accelerate loss of function.

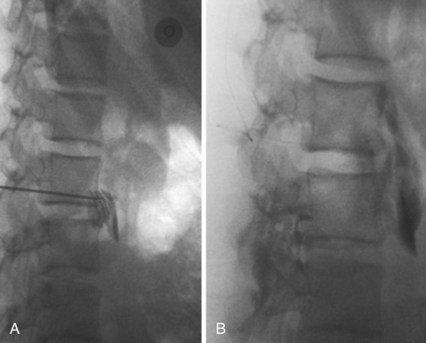

Several techniques enjoy popularity among pediatric pain specialists. For isolated limb CRPS, intravenous regional blockade with local anesthetic and adjuncts such as clonidine, ketamine, or ketorolac is performed. General anesthesia or deep sedation is frequently required because placement of intravenous catheters in the affected limb and inflation of the tourniquet are poorly tolerated. More invasive alternatives include placement of a lumbar sympathetic plexus catheter (Fig. 44-2) and a tunneled epidural catheter in the upper thoracic or lumbar area. The duration of infusion ranges from 3 to 5 days to as long as 4 to 6 weeks, and the procedure requires extensive logistical support. An alternative approach is to place a peripheral nerve catheter for a continuous block.38 Spinal cord stimulation and intrathecal drug delivery are rarely used for pediatric CRPS due to the overall good prognosis with more conservative treatment and the continued growth of the skeleton, which can change the area of paresthesias in the case of spinal cord stimulators.

Musculoskeletal and Rheumatologic Pain

Musculoskeletal pain is a recognized problem in children and adolescents, and back pain commonly affects adolescents.39,40–42 Although many factors are blamed for musculoskeletal pain (e.g., heavy backpacks, participation in sports, sedentary lifestyle, scoliosis, increased body mass index), only a few have been proved to contribute to musculoskeletal pain. According to one study, in more than half of cases the cause could not be identified, and only a minority of children had an underlying disease process (e.g., spondylolysis, infection, tumor, disk problem). Radiologic findings correlated poorly with the pain and failed to distinguish between individuals with pain and those without pain.42 Selected red flags for back pain are provided in Table 44-3. A care pathway for the evaluation and treatment of back pain in children and adolescents is presented in Table 44-7.

TABLE 44-7 Care Pathway for Back Pain

A special group of children with musculoskeletal pain are those with rheumatologic diseases. Most children referred to the rheumatologist’s office complain of musculoskeletal pain. Only some of them are diagnosed with a true rheumatologic disease; juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common form. Besides pain, the diseases often manifest as morning stiffness, fatigue, and sleep problems. The process may progress and cause joint deformities and destruction due to osteoporosis, with resulting growth abnormalities and functional disability. Management combines pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. The mainstay of therapy is the use of NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and rarely, opioids for severe breakthrough pain. The rheumatologist may prescribe agents such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, or systemic corticosteroids for severe flare-ups. Splints, physical therapy, and psychological interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy are often used.43 Children with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or other connective tissue disorders suffer from unstable joints that become very painful from repeated dislocations and mechanical stress.

Some young women present with fatigue, poor sleep, and pain or unusual tenderness in multiple sites. Fibromyalgia is more common in adolescents than expected, and it can be a significant problem. Therapy includes education, medications, and general restorative therapy, with a focus on aerobic reconditioning. Traditionally, tricyclic antidepressants and cyclobenzaprine have been used, and duloxetine and milnacipran are helpful in adults.44,45 As with many chronic pain conditions, cognitive-behavioral approaches are valuable components of treatment.46

Musculoskeletal pain is a particularly difficult problem in children with cerebral palsy.47 Spasticity itself can be painful, and the daily stretching exercises are reported to be painful by many children. Some children with cerebral palsy are nonverbal, making assessment even more difficult. The parents or guardians can provide information about how the child expresses pain and how the pain manifests during daily life. If diaper changes seem to hurt, the practitioner should suspect hip or perineal pain. Pain after eating or a history of hard stools may point to constipation-based abdominal pain. A careful and sometimes staged examination is required. A thoughtful, empirical approach to therapy and judicious use of radiologic and laboratory evaluations can often lead to the diagnosis (Table 44-8).

TABLE 44-8 Care Pathway for Nonverbal Patients

Medications: often on multiple agents at baseline and coordination with other practitioners is important; apply general principles in choosing medications; long-acting opioid is sometimes beneficial for refractory musculoskeletal pain; watch for worsening of constipation.

Behavioral medicine: often not possible if patient’s cognitive ability is too low, but the family sometimes can benefit because they carry a large burden when caring for children with multiple medical problems

Physical therapy: often already engaged; if not, engage for musculoskeletal pain or help therapist focus efforts of a particular region of the body

Site of pain is often unclear.

Do not forget to look in the ears.

If patient is spastic, strongly consider hip pathology (e.g., subluxation, bursitis, infection).

Constipation, gallbladder pain, and gastroesophageal reflux are possible.

These patients often require more testing than verbal patients.

Be careful with use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs because gastroesophageal reflux can be a problem and reporting abdominal pain as a signal of gastrointestinal side effects may not be possible.

Pain in Sickle Cell Disease, Trait, and Variants

Sickle cell disease is a hereditary disorder characterized by abnormal hemoglobin S (see Chapter 9). About 8% of African Americans carry the sickle gene. The homozygous form (sickle cell disease [HbSS]) manifests as a hemolytic anemia with unique vaso-occlusive features. The heterozygous form (sickle cell trait [HbAS]) is milder and manifests as a borderline anemia and rarely with vaso-occlusive features. Sickle cell/hemoglobin C disease (HbSC) has a clinical presentation similar to that of HbSS, but its vaso-occlusive episodes are fewer and usually less intense.

From a pain management perspective, the homozygous HbSS genotype manifests as acute pain attacks (e.g., pain crisis, vaso-occlusive episodes, acute chest syndrome) or as underlying chronic pain with acute exacerbations (e.g., avascular necrosis, vertebral collapse, joint involvement). Treatment frequently requires a multidisciplinary approach with close cooperation between the hematologist, psychologist, and pain physician.48 Most of the episodes can be managed at home with NSAIDs or acetaminophen, supplemented with opioids such as codeine or oxycodone or with tramadol. In severe cases, children often are hospitalized and treated with intravenous opioids, although they should be gradually weaned off the opioids as the primary process improves. For episodes of localized, hard-to-control pain or if acute chest syndrome develops, epidural analgesia can provide excellent relief.49 Rarely, children require opioid maintenance with long-acting preparations of morphine or oxycodone (Table 44-9). Hyperalgesia over the affected area suggests peripheral or central sensitization, although the role for neuropathic medications is undefined.

TABLE 44-9 Care Pathway for Sickle Cell Disease

Medications: opioid (often requires basal infusion for the first days); nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; consider neuropathic medication for hyperalgesia

Behavioral medicine: can be helpful, although learning techniques in the acute setting may be difficult; introducing this modality early in life may be more helpful

Physical therapy: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for localized pain

Medications: may involve chronic opioids; otherwise follows treatment of particular pain condition

Behavioral medicine: per particular pain condition; early involvement may reduce need for hospitalizations

Physical therapy: per particular pain condition; may have joint, bone, and deconditioning issues from recurrent vaso-occlusive episodes

Pain Pharmacotherapy

Pain treatment has received less study in children than adults, as it is true for much pediatric pharmacologic therapy. In the absence of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved indications and experimental data, off-label use of many medications used to treat chronic pain is common. In this situation, the decision to use a particular medication is most often based on extrapolation from adult literature, expert consensus, applied theory, and clinical judgment (see Chapter 6). Three categories of medications are available for consideration: nonopioid analgesics (i.e., NSAIDs and acetaminophen), opioid analgesics, and a broad spectrum of adjuvant analgesics, including anticonvulsants, antidepressants, muscle relaxants, local anesthetics, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, α2-agonists, and corticosteroids.

Opioids

Opioid agonists are used almost exclusively; agonist-antagonists have less popularity because of their ceiling effect and the potential to precipitate withdrawal when administered alongside a pure agonist. We typically use opioids in two scenarios. The first features opioids as a bridge while titrating other classes of medications to effect or while awaiting physical therapy or an intervention to exert its effect. In the second scenario, we use opioids as maintenance analgesics in carefully selected children (e.g., chronic musculoskeletal pain in a child with cerebral palsy, children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome). Medication is titrated in increments toward the main goals of optimal (although rarely complete) pain relief, improved function, and minimal adverse effects. Escalations are seen usually with exacerbations of the primary disease process. Common opioid adverse effects that occur with long-term use can be found in Table 44-10.

TABLE 44-10 Opioid Side Effects Associated with Chronic Use

A special medication in this group is methadone. Besides being an opioid agonist, methadone is also reasonably effective in controlling neuropathic components of pain. There are a few exceedingly important caveats for its use. It has a long half-life and presents a risk of accumulation leading to sedation and respiratory depression. The usual 1 : 1 methadone to morphine equianalgesia ratio does not work for dose conversion. The greater the dose of opioid being converted, the more skewed the conversion ratio; the methadone to morphine ratio ranged from 1 : 2.5 to 1 : 14.3 in one study.50 Because of the long half-life, dose adjustments should be made no more frequently than every 5 days. A unique adverse effect of methadone among opioids is its potential to prolong the QT interval and modestly increase the dispersion of repolarization on the electrocardiogram.51 Because the dispersion of repolarization is less than 100 msec, it remains unlikely that methadone can trigger torsades de pointes.

When a child who is taking long-term opioids presents in the operating room, a thorough medication history is essential for developing a perioperative plan. If the child has not taken a morning dose of opioid, that dose should be replaced by the intravenous route to avoid withdrawal. It is essential to convert the home medication into morphine equivalents, and the daily dose of home opioids should be provided as a baseline, with all further dosing being in addition to the baseline, to avoid pain at the time of emergence. Because of tolerance to long-term opioids, larger doses than usual may be required, and it is advisable (as in all children) to titrate to comfort in the immediate postoperative period and use the amount required to achieve optimal analgesia. Opioid consumption during the perioperative period may be more than three times that observed in patients not taking chronic opioids. Sparing use of opioids in the perioperative period results in poor pain management and withdrawal phenomena.52,53

Adjuvant Drugs

Anticonvulsants

Gabapentin and Pregabalin

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant with a complex mechanism of action. Its name is deceiving; gabapentin does not interact with the γ-aminobutyric (GABA)-ergic system. It binds to the α2-delta subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel54 and reduces the release of glutamate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This leads to decreased production of substance P, less activation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA) receptors on noradrenergic synapses, decreased transmitter release, and decreased neuronal activity.55 This mechanism is shared by gabapentin and pregabalin.

Topiramate

Best studied for the treatment of migraine headaches, topiramate can be applied to the full spectrum of neuropathic pain states.33 Because a unique adverse effect is appetite suppression, we may choose it for a patient with neuropathic pain who is concerned about weight gain. Topiramate has carbonic anhydrase–inhibiting properties and can result in metabolic acidosis and lead to renal stones in some cases.

Carbamazepine, Valproic Acid, and Phenytoin

The effectiveness of carbamazepine, valproic acid, and phenytoin has been discussed elswhere.56 Carbamazepine has proved effective in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia, spasticity in multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injury (compared with tizanidine). Phenytoin has been used alone or in combination with buprenorphine for cancer pain, and it has provided good pain relief in more than 60% of patients.

Antidepressants

Two major groups of antidepressants are used in the treatment of chronic pain: tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine) and the newer selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (e.g., venlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran).57 The efficacy of TCAs in the treatment of neuropathic pain has been confirmed in meta-analyses.58,59 The doses required to control chronic pain are usually less than those used in the treatment of depression. The effectiveness of antidepressants has been demonstrated in neuropathic and nonneuropathic pain such as fibromyalgia and low back pain.

Selective Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

Venlafaxines starting dose is 37.5 mg/day in adults, which can be increased by 37.5 mg every week up to 300 mg/day. Adverse effects include headaches, nausea, sweating, sedation, hypertension, and seizures. If the dose is less than 150 mg/day, the effects are mostly serotoninergic. If it exceeds 150 mg/day, the effects are mixed serotoninergic and noradrenergic. Duloxetine has antidepressant effects and analgesic effects for neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and back pain.45,57,60 It is usually started at 20 to 60 mg daily to a maximum dose of 120 mg/day. The major adverse effects are nausea, dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, and insomnia. Use of both medications in younger children is best left to those who prescribe the medications frequently because dosing has not been well established in the pediatric age group.

Muscle Relaxants

Cyclobenzaprine

Cyclobenzaprine is a centrally acting muscle relaxant. Its major adverse effects are somnolence, dizziness, and asthenia. The usual starting dose is 5 mg at night, which can be increased to 10 mg after 5 to 7 days unless the child has difficulties awakening in the morning. The dose can be escalated up to 10 mg three times per day.61

Tramadol

The doses used for chronic pain vary from 25 mg up to 100 mg four times per day (400 mg/day maximum).62 The dose should be limited in renally impaired children with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min up to a maximum of 200 mg/day and in those with impaired liver function up to 100 mg/day.

Local Anesthetics, α2-Adrenergic Receptor Agonists, Topical Agents, and N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Antagonists

The topical agent capsaicin, derived from hot chili peppers, is also helpful in managing neuropathic pain, but its application can cause a burning sensation where applied, which is often poorly tolerated. The topical lidocaine patch has been effective in the controlling symptoms of postherpetic neuralgia and has been used for localized myofascial pain, hyperpathia, and allodynia in other neuropathic conditions.63 Pharmacokinetic studies in adults have found minimal lidocaine blood concentrations, suggesting a large margin of safety,64 although similar studies have not been carried out in children.

Complementary Therapies

Acupuncture and its derivative, acupressure, originated in China and constitute an important part of traditional Chinese medicine (Fig. 44-3). In acupuncture, the body energy or qi (pronounced chi) circulates in body meridians and collaterals. Meridians and collaterals are pathways that represent body organ systems called the Zang-Fu organs. In Chinese medicine, pain is caused by obstruction in the circulation of qi in these channels due to multiple causes. Acupuncture has been used in acute and chronic pain conditions such as neck and back pain, dental pain, musculoskeletal and arthritic pain, CRPS, migraine, facial pain, and fibromyalgia. The data from randomized, controlled trials is controversial or insufficient to support or deny efficacy of acupuncture.65

Perquin CW, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Hunfeld JA, et al. Pain in children and adolescents: a common experience. Pain. 2000;87:51–58.

Ripamonti C, Groff L, Brunelli C, et al. Switching from morphine to oral methadone in treating cancer pain: what is the equianalgesic dose ratio? J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3216–3221.

Stanton-Hicks M, Baron R, Boas R, et al. Complex regional pain syndromes: guidelines for therapy. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:155–166.

Turk DC. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:355–365.

Wilder RT, Berde CB, Wolohan M, et al. Reflex dystrophy in children: clinical characteristics and follow-up of seventy patients. Am J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74:910–919.

1 Perquin CW, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Hunfeld JA, et al. Pain in children and adolescents: a common experience. Pain. 2000;87:51–58.

2 Burton AK, Clarke RD, McClune TD, Tillotson KM. The natural history of low back pain in adolescents. Spine. 1996;21:2323–2328.

3 Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, et al. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr. 1996;129:220–226.

4 Chalkiadis GA. Management of chronic pain in children [comment]. Med J Aust. 2001;175:476–479.

5 Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR, Powers SW, Vaught MH, Hershey AD. Depression and functional disability in chronic pediatric pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:341–349.

6 Hunfeld JA, Perquin CW, Bertina W, et al. Stability of pain parameters and pain-related quality of life in adolescents with persistent pain: a three-year follow-up. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:99–106.

7 Hunfeld JA, Perquin CW, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26:145–153.

8 Koh JL, Harrison D, Palermo TM, Turner H, McGraw T. Assessment of acute and chronic pain symptoms in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:330–335.

9 Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Suchindran C. Assessment of mobility, activities and pain in different subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:122–127.

10 Scharff L, Langan N, Rotter N, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and family characteristics of pediatric patients with chronic pain: a 1-year retrospective study and cluster analysis. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:432–438.

11 Lynch AM, Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR, Jones BA. Psychosocial risks for disability in children with chronic back pain. J Pain. 2006;7:244–251.

12 Turk DC. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:355–365.

13 Varni JW, Rapoff MA, Waldron SA, et al. Chronic pain and emotional distress in children and adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1996;17:154–161.

14 Stanton-Hicks M, Baron R, Boas R, et al. Complex regional pain syndromes: guidelines for therapy. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:155–166.

15 Rushton DN. Electrical stimulation in the treatment of pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:407–415.

16 Ophoff RA, Terwindt GM, Vergouwe MN, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Cell. 1996;87:543–552.

17 Buskila D, Neumann L. Genetics of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005;9:313–315.

18 Pace F, Zuin G, Di Giacomo S, et al. Family history of irritable bowel syndrome is the major determinant of persistent abdominal complaints in young adults with a history of pediatric recurrent abdominal pain. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3874–3877.

19 Roth-Isigkeit A, Thyen U, Stoven H, et al. Pain among children and adolescents: restrictions in daily living and triggering factors. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e152–e162.

20 Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527–1537.

21 Kellow JE, Azpiroz F, Delvaux M, et al. Applied principles of neurogastroenterology: physiology/motility sensation. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1412–1420.

22 Grundy D, Al-Chaer ED, Aziz Q, et al. Fundamentals of neuro-gastroenterology: basic science. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1391–1411.

23 Di Lorenzo C, Colletti RB, Lehmann HP, et al. Chronic abdominal pain in children: a technical report of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:249–261.

24 Grigoleit HG, Grigoleit P. Peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:601–606.

25 Robins PM, Smith SM, Glutting JJ, Bishop CT. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral family intervention for pediatric recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:397–408.

26 Youssef NN, Rosh JR, Loughran M, et al. Treatment of functional abdominal pain in childhood with cognitive behavioral strategies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:192–196.

27 Brna P, Dooley J, Gordon K, Dewan T. The prognosis of childhood headache: a 20-year follow-up. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1157–1160.

28 Abu-Arefeh I, Russell G. Prevalence of headache and migraine in schoolchildren. BMJ. 1994;309:765–769.

29 Abu-Arafeh IA, Russell G. Epidemiology of headache and migraine in children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1993;35:370–371.

30 Ferrari MD. Migraine. Lancet. 1998;351:1043–1051.

31 Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215–2224.

32 Bussone G, Usai S, D’Amico D. Topiramate in migraine prophylaxis: data from a pooled analysis and open-label extension study. Neurol Sci. 2006;27(Suppl 2):S159–S163.

33 Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, LeCates S, Kabbouche M. Effectiveness of topiramate in the prevention of childhood headaches. Headache. 2002;42:810–818.

34 D’Amico D, Grazzi L, Usai S, Moschiano F, Bussone G. Topiramate in migraine prophylaxis. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(Suppl 2):S130–S133.

35 Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain. 2002;95:119–124.

36 Wilder RT, Berde CB, Wolohan M, et al. Reflex dystrophy in children: clinical characteristics and follow-up of seventy patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:910–919.

37 Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Lau J. Local anesthetic sympathetic blockade for complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2005. CD004598

38 Lee BH, Scharff L, Sethna NF, et al. Physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral treatment for complex regional pain syndromes. J Pediatr. 2002;141:135–140.

39 Kristjansdottir G. Prevalence of self-reported back pain in school children: a study of sociodemographic differences. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155:984–986.

40 Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO. At what age does low back pain become a common problem? A study of 29,424 individuals aged 12-41 years. Spine. 1998;23:228–234.

41 Ehrmann Feldman D, Shrier I, Rossignol M, Abenhaim L. Risk factors for the development of neck and upper limb pain in adolescents. Spine. 2002;27:523–528.

42 Jones GT, Macfarlane GJ. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:312–316.

43 Anthony KK, Schanberg LE. Pediatric pain syndromes and management of pain in children and adolescents with rheumatic disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:611–639. vii

44 Kyle JA, Dugan BD, Testerman KK. Milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1422–1429.

45 Arnold LM, Rosen A, Pritchett YL, et al. A randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Pain. 2005;119:5–15.

46 Kashikar-Zuck S, Swain NF, Jones BA, Graham TB. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral intervention for juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1594–1602.

47 McKearnan KA, Kieckhefer GM, Engel JM, et al. Pain in children with cerebral palsy: a review. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36:252–259.

48 Ballas SK. Pain management of sickle cell disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2005;19:785–802.

49 Yaster M, Tobin JR, Billett C, et al. Epidural analgesia in the management of severe vaso-occlusive sickle cell crisis. Pediatrics. 1994;93:310–315.

50 Ripamonti C, Groff L, Brunelli C, et al. Switching from morphine to oral methadone in treating cancer pain: what is the equianalgesic dose ratio? J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3216–3221.

51 Krantz MJ, Lowery CM, Martell BA, Gourevitch MN, Arnsten JH. Effects of methadone on QT-interval dispersion. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:1523–1529.

52 de Leon-Casasola OA, Myers DP, Donaparthi S, et al. A comparison of postoperative epidural analgesia between patients with chronic cancer taking high doses of oral opioids versus opioid-naive patients. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:302–307.

53 Rapp SE, Ready LB, Nessly ML. Acute pain management in patients with prior opioid consumption: a case-controlled retrospective review. Pain. 1995;61:195–201.

54 Sills GJ. The mechanisms of action of gabapentin and pregabalin. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:108–113.

55 Coderre TJ, Kumar N, Lefebvre CD, Yu JS. Evidence that gabapentin reduces neuropathic pain by inhibiting the spinal release of glutamate. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1131–1139.

56 Wiffen P, Collins S, McQuay H, et al. Anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2005. CD001133

57 Maizels M, McCarberg B. Antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs for chronic non-cancer pain. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:483–490.

58 McQuay HJ, Tramer M, Nye BA, et al. A systematic review of antidepressants in neuropathic pain. Pain. 1996;68:217–227.

59 Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Wiffen P. Antidepressants and anticonvulsants for diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia: a quantitative systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:449–458.

60 Prakash A, Lobo E, Kratochvil CJ, et al. An open-label safety and pharmacokinetics study of duloxetine in pediatric patients with major depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22:48–55.

61 Romano TJ. Fibromyalgia in children;diagnosis and treatment. W V Med J. 1991;87:112–114.

62 Rose JB, Finkel JC, Arquedas-Mohs A, et al. Oral tramadol for the treatment of pain of 7-30 days’ duration in children. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:78–81.

63 Davies PS, Galer BS. Review of lidocaine patch 5% studies in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Drugs. 2004;64:937–947.

64 Gammaitoni AR, Alvarez NA, Galer BS. Safety and tolerability of the lidocaine patch 5%, a targeted peripheral analgesic: a review of the literature. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:111–117.

65 Eshkevari L. Acupuncture and pain: a review of the literature. AANA J. 2003;71:361–370.