Chapter 38 CHRONIC NON-VIRAL HEPATITIS

INTRODUCTION

Definition

Chronic non-viral hepatitis is a disease of the liver characterised by chronic inflammation and liver cell necrosis, that is due to non-viral causes and which persists without improvement for at least 6 months. However, in autoimmune hepatitis, the 6- month requirement is no longer required to establish chronicity as the condition may present acutely. Also, drug or toxin-induced liver disease is sometimes considered a chronic disease when the duration of liver inflammation extends beyond 3 months.

CAUSES

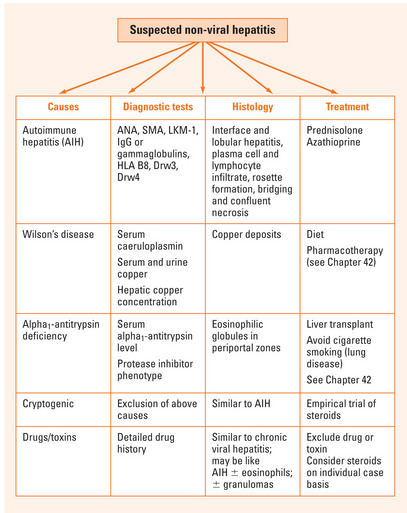

The causes of non-viral chronic hepatitis are listed in Table 38.1. The principal cause is autoimmune hepatitis. Less common causes include drug-induced hepatitis and cryptogenic hepatitis. The hereditary metabolic liver diseases, Wilson’s disease and alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, may also cause a chronic hepatitis-like picture. Diseases mimicking chronic hepatitis include non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis.

| Cause | Specific histology |

|---|---|

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Interface and lobular hepatitis, plasma cell and lymphocytic infiltrate, rosette formation, bridging and confluent necrosis |

| Drugs and toxins | Similar to chronic viral hepatitis; may be autoimmune hepatitis-like; ± eosinophils; ± granulomas |

| Cryptogenic | Similar to autoimmune hepatitis |

| Wilson’s disease | Copper deposits |

| Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency | Eosinophilic globules in periportal zones |

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) accounts for about 20% of cases of chronic hepatitis. The disease has a female preponderance, affects all ages and has a worldwide distribution. There is a genetic association with the human leucocyte antigens B8, DR3 and DR4. The cause of AIH is unknown. Autoantibodies including antinuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-smooth muscle antibody (SMA) are very common but not specific for the disease or of pathogenetic significance. At least two types of AIH are recognised.

Cryptogenic hepatitis

Around 10%–20% of patients with chronic hepatitis have no definable cause and are classified as cryptogenic hepatitis. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. It may be due to an unknown virus, burnt-out non-alcoholic steatohepatitis or an autoimmune process. The condition may clinically resemble type 1 AIH in age and sex distribution, necroinflammatory activity, HLA status and response to therapy.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Autoimmune hepatitis

The clinical features of severe AIH are shown in Table 38.3. An acute onset is observed in about 25% of patients. Fulminant hepatitis occurs rarely. Common extrahepatic associations are autoimmune thyroid disease, ulcerative colitis and synovitis.

| Clinical features at presentation | Frequency (%) |

| Symptoms | |

| • Fatigue and loss of energy | 85 |

| • Dark urine and/or light stools | 77 |

| • Abdominal pain/discomfort | 48 |

| • Anorexia, nausea | 30 |

| • Pruritus | 36 |

| • Polymyalgias | 30 |

| • Diarrhoea | 28 |

| • Amenorrhoea (women) | 89 |

| • Cosmetic changes (facial rounding, hirsutism, acne) | 19 |

Diagnostic approach

The key objectives in the assessment of chronic hepatitis are to establish:

The diagnostic tests for chronic hepatitis are listed in Table 38.4.

TABLE 38.4 Diagnostic tests for viral and non-viral causes of chronic hepatitis

| Cause | Diagnostic investigations |

| Viral | |

| • Chronic hepatitis B | HBsAg, HBeAg, HBV DNA |

| • Chronic hepatitis C | Anti-HCV Ab, HCV RNA |

| • Chronic hepatitis D | Anti-HDV IgM, HDV RNA |

| Non-viral | |

| • Autoimmune hepatitis | ANA, SMA, LKM-1; IgG or gammaglobulin level; HLA B8, Drw3, Drw4 |

| • Wilson’s disease | Serum caeruloplasmin level, serum and urinary copper studies, hepatic copper concentration |

| • Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency | Serum alpha1-antitrypsin level, protease inhibitor phenotype |

| • Drug-induced | Careful drug history |

| • Cryptogenic | Exclusion of above causes |

Ab = anitbody; ANA = antinuclear antibodies; HBeAg = hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV = hepatitis B virus; HCV = hepatitis C virus; HDV = hepatitis D virus; HLA = human leucocyte antigen; IgG = immunoglobulin G; LKM-1 = antibodies to liver-kidney microsome type 1; SMA = anti-smooth muscle antibody.

INVESTIGATIONS

Liver function tests

In AIH, serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) are elevated: serum aminotransferase levels reflect the severity of inflammatory activity and prognosis (Table 38.5). Most patients with AIH have serum AST levels <500 U/L at presentation. Serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels are usually normal to less than 2-fold elevated. Hyperbilirubinaemia is common in severe AIH. A reduced serum albumin concentration and/or prolonged international normalised ratio (INR) indicate an advanced stage of liver disease.

TABLE 38.5 Markers of severity of inflammation in autoimmune hepatitis

| Inflammatory activity | |

| Severe | Mild–moderate |

Serum globulins

Hypergammaglobulinaemia is present in more than 80% of cases of AIH and is a marker of disease severity (Table 38.5). A polyclonal increase in serum immunoglobulins is also common, particularly the IgG fraction. Elevated serum globulin concentrations are also a feature of most cases of cryptogenic hepatitis.

Liver biopsy

Percutaneous liver biopsy is generally recommended in the absence of contraindications. To confirm the clinical diagnosis, grade the severity of necroinflammation, stage the degree of fibrosis and, in the case of AIH, monitor treatment response. A simple scoring system for classifying necroinflammatory activity and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis is shown in Table 38.6. Histology plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis of AIH (see Table 38.7). Classic features are interface hepatitis with lymphocytic infiltrates, plasma cells and piecemeal necrosis. Bridging and confluent necrosis indicate severe AIH and a poor prognosis if untreated. Key histologic features of the other differential diagnoses are shown in Table 38.1.

| Grade | Necroinflammatory activity | Fibrosis |

| 0 | None or minimal | None |

| 1 | Portal inflammation; lobular inflammation with no necrosis | Expanded fibrotic portal tracts |

| 2 | Mild piecemeal necrosis; focal lobular necrosis | Periportal or portal-portal septa but intact architecture |

| 3 | Moderate piecemeal necrosis; severe focal cell damage in lobules | Fibrosis with architectural distortion |

| 4 | Severe piecemeal necrosis, bridging necrosis in lobules | Cirrhosis |

TABLE 38.7 Scoring system for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis parameter

| Autoimmune hepatitis parameter | Score |

| Gender | |

| Female | +2 |

| Male | 0 |

| Serum biochemistry | |

| Ratio of elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase vs aminotransferase | |

| >3.0 | −2 |

| 1.5–3 | 0 |

| <1.5 | +2 |

| Total serum globulin, gammaglobulin, or IgG times upper limit of normal | |

| >2.0 | +3 |

| 1.5–2.0 | +2 |

| 1.0–1.5 | +1 |

| <1.0 | 0 |

| Autoantibodies (titres by immunofluorescence) | |

| ANA, SMA, LKM-1 | |

| >1:80 | +3 |

| 1:80 | +2 |

| 1:40 | +1 |

| <1:40 | 0 |

| Antimitochondrial antibody | |

| Positive | −4 |

| Negative | 0 |

| Hepatitis viral markers | |

| Negative | +3 |

| Positive | −3 |

| Other aetiological factors | |

| History of drug usage | |

| Yes | −4 |

| No | +1 |

| Alcohol usage | |

| <25 g/day | +2 |

| >60 g/day | −2 |

| Genetic factors: HLA DR3 or DR4 | +1 |

| Other autoimmune diseases | +2 |

ANA = antinuclear antibodies; HLA = human leucocyte antigen; LKM-1 = antibodies to liver-kidney microsome type 1; SMA = anti-smooth muscle antibody.

DIAGNOSIS

Autoimmune hepatitis

A scoring system that grades individual components of the syndrome may be applied to confirm the diagnosis (Table 38.7). Using this system, a definite diagnosis of AIH can be made with aggregate scores of >15 before treatment and >17 after treatment. Probable AIH corresponds to pre- and post-treatment scores of 10–15 and 12–17 respectively.

Other conditions

Cryptogenic hepatitis is a diagnosis of exclusion requiring negative viral and autoantibody markers in the absence of relevant drug or toxin exposure. Drug-induced chronic hepatitis requires a compatible drug-history and the exclusion of viral and other non-viral causes. Wilson’s disease is diagnosed on the basis of low serum caeruloplasmin levels, elevated 24-hour urinary copper and hepatic copper overload as demonstrated by staining and/or measurement of hepatic copper concentration.

TREATMENT

Autoimmune hepatitis

Standard treatment regimens are prednisolone alone or prednisolone combined with azathioprine (Table 38.8). Prednisolone monotherapy is preferred in pregnancy and those with cytopenias or active malignancy.

| Monotherapy regimen | Combination regimen | |

| Induction | ||

| • Prednisolone | 60 mg for 1 week, 40 mg for 1 week, 30 mg for 2 weeks; 15–20 mg for maintenance | 30 mg for 1 week, 20 mg for 1 week, 15 mg for 2 weeks; 10 mg for maintenance |

| • Azathioprine | None | 50–100 mg for maintenance |

| Upon remission* | ||

| • Prednisolone | Taper by 2.5 mg every week | Taper by 2.5 mg every week |

| • Azathioprine | NA | Reduce by 25 mg every 3 weeks |

| Relapse | ||

| • Prednisolone | Same as induction schedule | Same as induction schedule |

| • Azathioprine | None | 50–100 mg maintenance |

* Treatment should be for 12–24 months and for at least 3–6 months after clinical and biochemical remission is achieved.

The goal of treatment is to induce remission as defined in Table 38.9. For both treatment schedules, remission rates are around 65% after 18 months’ therapy. Treatment should be continued for between 12 and 24 months and at least 3–6 months after clinical and biochemical remission is achieved. Prednisolone is then slowly withdrawn over 6 weeks with regular monitoring of liver function tests and globulin levels during follow-up. Relapse occurs within 6 months in up to 50% of cases. This rate is reduced to 20% if histologic remission is documented prior to drug withdrawal. Treatment of relapse is with the original treatment schedule.

TABLE 38.9 End points of treatment and appropriate management response

| End point | Definition | Response |

| Remission | Asymptomatic and AST levels ≤2-fold times normal and/or normal liver or portal hepatitis or inactive cirrhosis on biopsy | Taper off prednisolone over 6–12 weeks and monitor |

| Incomplete response | No remission within 2 years of treatment | Continue drug(s) on lowest possible dose to keep AST ≤5-fold normal or achieve histologic remission |

| Treatment failure | Clinical and/or biochemical deterioration despite treatment compliance | Prednisolone 60 mg/day or prednisolone 30 mg/day plus azathioprine 150 mg/day for at least 1 month |

| Drug intolerance | Severe side effects of treatment: marked weight gain, psychosis, symptomatic osteoporosis, unstable diabetes (prednisolone); and/or severe cytopenia, fever, neoplasm, rash, nausea/vomiting (azathioprine) | Dose reduction by 50%; complete withdrawal if no improvement or toxicity severe |

Other treatment end-points that may occur are an incomplete response, treatment failure and intolerance of drug therapy (Table 38.9). Patients with an incomplete response typically require long-term maintenance immunosuppressive therapy at the lowest possible dose to maintain AST levels <5-fold normal. Treatment failure occurs in 10%–15% of patients and requires a trial of high-dose corticosteroids or combination therapy in higher doses (Table 38.9). Liver transplantation should be considered in those who fail to respond and/or develop liver failure, or are fulminant cases. Therapeutic options for drug intolerance are dose reduction by 50% or withdrawal of the implicated drug and to use a higher dose of the tolerated agent. New therapies for difficult-to-treat patients include tacrolimus, cyclosporin A, mycophenolate mofetil, ursodeoxycholic acid and budesonide.

Cryptogenic hepatitis

Patients with cryptogenic hepatitis and autoimmune features, such as raised serum IgG hypergammaglobulinaemia and concurrent immunologic disorders, often respond well to corticosteroid therapy. In such patients, an empirical trial of corticosteroids is worthwhile using one of the two treatment schedules outlined in Table 38.8.

SUMMARY

Key objectives in the assessment are to establish the cause, the degree of hepatic necroinflammation and fibrosis and the severity of the chronic liver disease (Figure 38.1). Treatment depends on the cause. Steroids are important in autoimmune hepatitis (together with azathioprine) and may play a role in drug- or toxin-induced hepatitis and cryptogenic hepatitis.

Czaja AJ. Current concepts in autoimmune hepatitis. Am Hepatol. 2005;4:6-24.

Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Distinctive clinical phenotype and treatment outcome of type I autoimmune hepatitis in the elderly. Hepatology. 2006;43:532-538.

Hall PD. Chronic hepatitis: an update with guidelines for histopathological assessment of liver biopsies. Pathology. 1998;30:369-380.

Heneghan MA, McFarlane IG. Current and novel immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;35:7-13.

Manns MP, Strassburg CP. Autoimmune hepatitis: clinical challenges. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1502-1517.