Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

Clinical features

Where problems do arise, patients commonly complain of symptoms of anaemia, lymphadenopathy, unusually persistent or severe infections and weight loss. The most frequent findings on examination are lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. In more advanced cases other tissues such as skin, the gastrointestinal tract, the central nervous system, lungs, kidneys and bone may be infiltrated by leukaemic cells. Occasionally there is transformation into a poorly differentiated large cell lymphoma which carries a poor prognosis (Richter syndrome). The immunodeficiency in CLL is caused mainly by hypogammaglobulinaemia, which predisposes to infections (Fig 23.1) and also accounts for an increased incidence of other malignancies.

Diagnosis

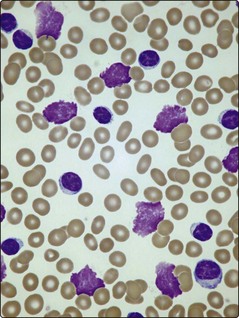

The diagnosis is suggested by a high lymphocyte count confirmed by the blood film appearance. Lymphocyte counts in CLL exceed 5 × 109/L and may reach levels of 500 × 109/L or more. The cells resemble normal mature lymphocytes but are often slightly larger with a tendency to burst during preparation of blood films, resulting in ‘smear cells’ (Fig 23.2). Unexplained persisting lymphocytosis in an elderly person should always suggest CLL. The diagnosis is made by proving that the lymphocytosis is a proliferation of clonal B-cells; this is most simply demonstrated by using in situ or flow cytometry techniques (see p. 21) to show that the cells have characteristic B-lymphocyte antigens and that a single immunoglobulin light chain (kappa or lambda) exists on the cell surface (i.e. it is a monoclonal population). The bone marrow aspirate shows increased numbers of small lymphocytes and a trephine biopsy is worthwhile as the pattern of lymphocyte infiltration gives prognostic information. The blood film appearance may suggest autoimmune haemolysis or autoimmune thrombocytopenia, both of which can complicate CLL.

Staging

Staging is important in CLL as it helps in making a rational decision as to whether to commence treatment, and it also gives useful prognostic information. The easiest method is the Binet adaptation of the previous Rai system (Table 23.1); this is simple to apply and correlates closely with survival.

Table 23.1

| Stage A | No anaemia or thrombocytopenia |

| Fewer than three lymphoid areas1 enlarged | |

| Stage B | No anaemia or thrombocytopenia |

| Three or more lymphoid areas enlarged | |

| Stage C | Anaemia (Hb less than 100 g/L) and/or platelets less than 100 × 109/L |

1Lymphoid areas are cervical, axillary and inguinal lymphadenopathy (uni- or bilateral), spleen and liver.

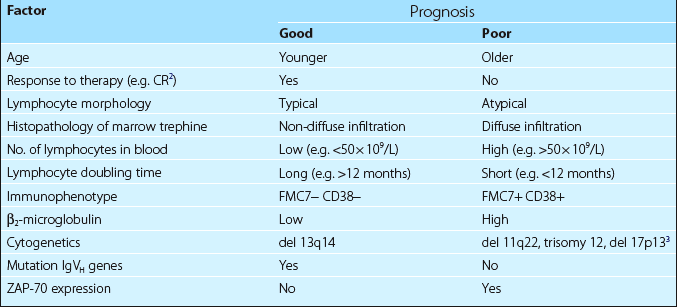

Other variables are increasingly important in predicting prognosis. As gene sequencing is expensive and time-consuming, expression of the signalling molecule ZAP-70 can be used as a surrogate marker for unmutated IgVH genes and a poor prognosis (Table 23.2).

Management

Choice of treatment

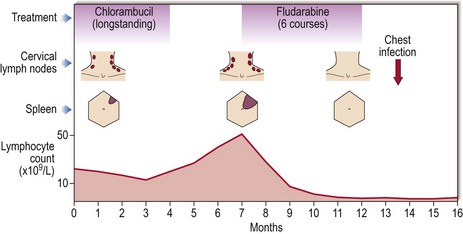

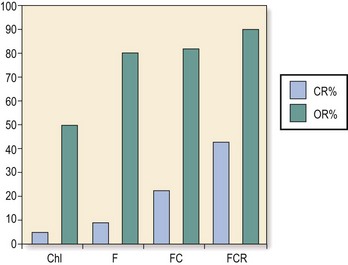

Treatment should be commenced when the patient develops significant symptoms, when the disease is progressing rapidly or when it is already at an advanced clinical stage. For many years, oral chlorambucil (usually given intermittently) has been the traditional first-line agent for treatment. Chlorambucil is still useful in older patients and where there is significant comorbidity but it has now been mostly replaced in first-line treatment by the more effective purine analogue fludarabine. The combination of fludarabine with other agents has brought benefits with higher levels of complete remission (Fig 23.3) translating into a survival advantage; the current favoured regimen is a combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and the monoclonal antibody rituximab (anti-CD20). The alkylating agent bendamustine is a promising new approach to first-line treatment. Steroids (e.g. prednisolone) are best reserved for patients with pancytopenia or autoimmune complications such as haemolysis or immune thrombocytopenia. Treatment decisions are increasingly influenced by risk factors (see Table 23.2) in addition to stage – for instance, patients with 17p deletions are known to respond poorly to fludarabine and may be considered for more novel therapies such as alemtuzumab (anti-CD52) and ibrutinib.

Fig 23.3 Efficacy of fludarabine in CLL.

Fludarabine, usually in combination with other agents, is now the favoured first-line treatment. Its general superiority over chlorambucil is demonstrated in this patient – the chest infection is a reminder that fludarabine is, however, more immunosuppressive than chlorambucil.

Fig 23.4 The combination of different agents as first-line treatment for CLL leads to improved response rates.

(Reproduced from Hallek M 2009 State-of-the-art treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. American Society of Haematology Educational Book). CR, complete remission; OR, overall response; Chl, chlorambucil; F, fludarabine; C, cyclophosphamide; R, rituximab.